Drodriquez Williams watched the news that night about the twin towers at the World Trade Center collapsing Sept. 11, 2001. It shocked the 9-year-old boy. Every time he saw the footage of the collapsing skyscrapers in New York City, he felt the need to do something grow deeper. Immediately, he knew that he wanted to join the military. Williams never wanted any other job. That day, as he watched his country under attack, he told his mom about his intentions. He then told his brother, his teachers and counselors—anyone who would listen—that he wanted to join the U.S. Navy.

"I didn't want to do the Marines," Williams, now 19, said. He smiles about it, as if it is obvious that the Navy is a better option. His dimples could convince a skeptic he is right.

Williams still wants to join the Navy, but he only has an occupational degree instead of a high-school diploma. A counselor decided when he was in 8th grade at Whitten Middle School that's all he would need, despite Williams repeatedly declaring his goal of joining the military. As he learned a few years later, the military wouldn't accept this certificate for enlistment. The recruiter wanted that diploma.

Williams had some problems at Whitten Middle School, like many energetic and playful young men testing limits in junior high. He talked and smiled a lot, trying to charm teachers and classmates. When he was in 7th grade, he won third place in the science fair with a barometer he made out of a coffee can and a balloon.

Now he is working full-time at Chick-fil-A in Clinton and trying to get a second job at Walmart. He spends most of his off time playing football and basketball with friends, although occasionally he plays "Call of Duty" or some other video game. He likes to paint and has a large self-portrait propped near the fireplace in his south Jackson home. He sings and listens to lots of music, especially Kris Allen, the Black Eyed Peas and Taylor Swift.

"Yeah, I listen to her. If you listen to her stuff, it's pretty good," he says. "Like 'Romeo's Song.'"

Williams has a steady girlfriend who he says is easy to commit to. He wears a black-and-blue fitted sweater jacket without a piece of lint or a single loose thread in sight. "I like to look good," he says. And then he smiles again with those dimples.

He's so charming it's hard to believe he's been in trouble with the law. Some of his stories seem far-fetched—he says he got in trouble at school once because he wouldn't smile. A teacher told him another time in the cafeteria to drink his milk, and he told her right back he did not want to. Something about the way he expressed that led to a disciplinary action.

All this is normal—a teenager, acting like kids do sometimes, experiments with power while school officials insist on order and discipline. For some students, though, a smart mouth can lead to jail, while others displaying the same behavior might only be mischievous, interesting characters who go on to college.

More than once, talking back landed Williams in Capital City Alternative School, the holding place where suspended or expelled JPS students go. When he was in 8th grade, a teacher accused him of stealing earphones from her. He denied it passionately with sarcasm and what the principal determined was disrespect.

Smile or Else

Williams sat one morning bored to tears in his 8th-grade social-studies class at Capital City. He knew lunch was coming up soon and wondered what he might eat. He wasn't paying attention to the lesson or to his classmates. "I never smiled. I never talked," he said.

That particular class only had a handful of students, and only three of them were boys. The other two boys got into an argument and started fighting. Williams says he doesn't remember what got them started. The teacher went in the hall to get the uniformed school police. The police came in yelling.

"Man, I ain't even did nothing," Williams said.

"Don't say nothing, just sit on the floor," they yelled at all the boys, including Williams. They took the boys in the hallway and made them sit Indian style, legs folded, facing the wall.

The school police handcuffed each boy, then one by one took them to the school gym and auditorium. The officers handcuffed Williams to a metal stair railing that leads down just a few steps to an exit. They left him there all day. When school got out, the officers took Williams to jail downtown. He spent 21 days in the juvenile detention center. When he got out, he had to return to Capital City.

Williams wasn't smiling three weeks after the incident when he returned to Capital City. Serious, grim-faced security officers and administrators searched all students as they entered the school, as they do every day. Williams wasn't happy about any of it. The adults in charge noticed.

"You need to smile there, or you're fixing to go to jail," a school official told him. She wasn't making a joke and called over a uniformed JPS officer.

"He better smile, or we are fixing to go down that path," the officer said.

Williams had been a student at Capital City more than once. His middle school and high school had suspended him before for being sarcastic or not doing what he was told. He had to attend the alternative school during those times. One time, he was suspended because a teacher had accused him of stealing earphones from her. She called him a thief. He said teachers searched him but found nothing. Another time, a teacher accused him of having bullets, but school officers searched him and again found nothing.

A couple of years later, when Williams was in 10th grade at Wingfield High School, he was at football practice with his brother when a fight broke out in front of campus. Williams said he wasn't involved in it. A school police officer told him he had to leave the campus. His mother had told him to never leave without calling her, and he intended to do as she said. The JPS officers wouldn't let him call his mom. When the school police threatened to take him to jail, Williams ran. He and his mother are still resolving the 2009 issue with the school district. It involves phone calls and endless paperwork.

Bubbling Up

Ja'Eisha Scott did not want to participate in her kindergarten lesson March 14, 2005. She did more than pout about it. The 5-year-old St. Petersburg, Fla., student threw a fit. The teacher tried to calm her but couldn't. Following her district's procedures, the teacher next got the principal involved. The little girl continued her tantrum as she tore papers off a bulletin board, climbed on a table and even punched the principal. School officials called her mom, who said she was on her way to the school. It took about an hour for the girl's mother to get there.

Meanwhile, the principal followed school policy and called the police. Before the cops got there, the little girl had calmed down and was sitting in a chair quietly. Three police officers approached the child, forcing her arms behind her. Ja'Eisha started crying. The police snapped the handcuffs on and led the wailing girl to a police car.

The teachers and the police followed zero-tolerance policies in handling the misbehaving girl. That means no exceptions—at least in theory. Students of all ages who violate conduct codes face harsh punishments. Many school districts have little choice in the matter as federal funding became increasingly attached to the creation of these policies in the past two decades. This zero-tolerance approach has criminalized many children, conditioning them to fit in when they get to prison.

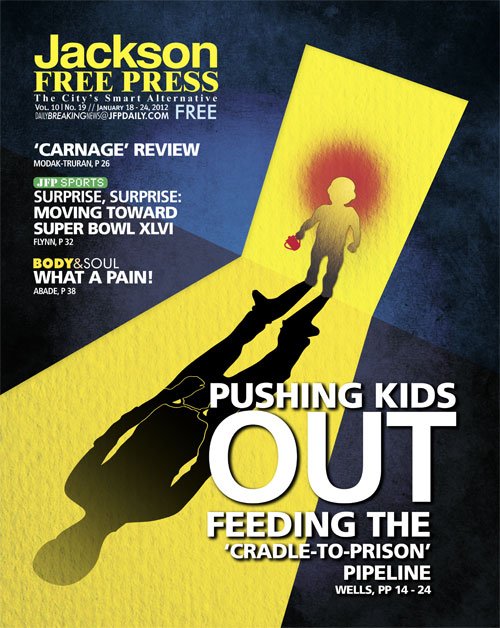

The Children's Defense Fund released "America's Cradle to Prison Pipeline Report" in 2007, examining what it calls a "national crisis at the intersection of poverty and race." School systems are more likely to identify black children at an early stage as potential criminals for the same behavior as other students. The self-fulfilling prophecy affects programs and budgets that might otherwise encourage those students to go to college or pursue a career path.

Portia Ballard Espy, chief administrative officer for the CDF Southern Regional Office in Jackson, says several areas lead to streamlining a child from cradle to prison: having a single mom, being a child of color, being poor, going to a poor-quality school or lacking health care. "Sometimes things transpire in a child's life, sometimes before they are born," Espy said. "They are factors we have control over."

But of all the things that criminalize a young child, zero-tolerance policies in schools might be the worst. Born out of the 1980s drug wars and the 1990s school shootings, zero-tolerance policies severely punish children for expected, normal misbehavior in school and can lead to some going to jail for small offenses. School officials can suspend or expel a student who yells to her buddy in the hall or who does not tuck in his shirt. If a sassy child talks back in such a situation, school policy might dictate a call to the police who may take the child away in handcuffs.

When Espy attended a 2010 conference on zero tolerance a couple of years ago, a speaker asked audience members to stand if they had ever spoken out of turn in class when they were kids. Many stood. Then he asked them to stand if they had ever gotten in trouble at school for wearing the wrong thing—such as a skirt a half-inch too short. More adults stood, including Espy. "It was stuff all of us had done," she said.

"If you were in school today under current policies, you could be incarcerated," the speaker told them.

"It really brought the point home. We simply used to go to principal's office when we got in trouble. The most humiliating thing was being put outside the room in the hallway. Now children are handcuffed and taken out of the classroom," Espy said.

The Advancement Project, a national civil-rights advocacy group, released a March 2010 report on zero-tolerance policies that made similar observations about how unfairly schools treat blacks, Hispanics and poor kids. "Test, Punish and Push Out" also examined the connection between such policies and high-stakes testing, saying the two together funnel children from school to prison.

Earlier this year, the Annie E. Casey Foundation released "No Place for Kids: the Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration." The study reports that sometimes for minor offenses children can wind up in training schools, reformatories or youth correction centers. Too often, it starts with school problems ranging from dress-code violations to making rude comments.

The kids who really feel the brunt of draconian policies tend to have attention deficit disorder or other undiagnosed psychological problems. Instead of a child getting help, the severe punishments hurt the fidgeting or daydreaming students academically. They get pulled out of class and get further behind in their schoolwork.

The large majority of students punished are black boys, Espy said. Early advocates of zero tolerance insisted that harsh discipline for all students, regardless of violation or circumstance, was the most fair system. A white daughter of the school-board president would get no special treatment if she were caught with a joint at school, for example. Zero tolerance leaves no room for exceptions, meaning that it's bad for all children, and worse for those traditionally discriminated against.

"Where is the common sense?" Espy wants to know.

"Teachers have a hard job." She knows that. Her parents are retired teachers, and her sister is a former teacher. "If you have a disruptive child in your class, you are going to figure out the easiest way to deal," she said. School policies often prescribe every course of action and leave no wiggle room when the next step in the protocol is calling the cops. School resource officers are real police trained to deal with dangerous criminals.

Criminalizing Children

While Espy stresses that schools need order and discipline, she says criminalizing children's behavior only conditions them to believe that they belong in alternative schools, juvenile detention facilities and jail, she said. Children assume they are destined for jail pretty early in life. They learn it's the norm.

"We adults can do something about that," Espy said. That includes identifying best practices for school police officers. Additional training is important for those officers taught to deal with adult offenders and suspects, not school children.

Another important step children's advocates can take is making sure parents understand what zero tolerance means. Espy said more and more parents and other adults are speaking against the destruction these policies have had on children.

"It's bubbling up. You can expect to hear more," she said.

Charles Perry at Jackson-based PERICO Institute, a nonprofit organization, is researching 150 school-district policies in Mississippi for Espy's office. The research shows districts have no consistency in their policies, she said. The study covering the past decade is incomplete, but with about half the districts surveyed, several trends already pop.

In general, the policies affect more blacks than whites. Schools use corporal punishment more on black males than white males for the same offenses. So far in the research, the CDF found no evidence of white girls getting spanked in Mississippi for the past few years, although some black girls did get the punishment. Black boys get the majority of the paddlings.

In schools across the nation, blacks and members of other minorities get disciplined more often than white students although all kids misbehave in similar ways at the same rates. That's long been the trend. In a 2000 Indiana Education Policy Center report, researchers examined 25 years of evidence showing schools punished black students more often and more severely.

In "The Color of Discipline," lead author Russell Skiba of Indiana University and other researchers found that boys in general did get sent to the principals' office more often and also got more suspensions than girls. They could link that to more misbehavior. But they found something else in their data.

"(N)o support was found for the hypothesis that African American students act out more than other students. Rather, African American students appear to be referred to the office for less serious and more subjective reasons," the report stated.

"In particular, we were struck during the preparation of this manuscript by the virtual absence of empirical support for the popular hypothesis that African American students are disciplined more because they act out more."

At a Jan. 21 Dismantling the Cradle to Prison Pipeline summit in Jackson, 300 or so people will brainstorm solutions and alternatives to racial disparity and zero tolerance. Espy mentioned the peer mediation program at Blackburn Middle School that Malkie Schwartz, director of community engagement at the Institute of Southern Jewish Life, started a couple of years ago. Blackburn has seen a decrease in the number of incidents and fighting since it began the in-house, peer-resolution experiment. With JPS approval, Schwartz has taken the program to Jim Hill High School, where 30 students are participating this year.

The students learn how to resolve conflicts, new ways to talk to each other and more detailed instruction to listen and solve problems. Through peer mediation, the students can each come and confidentially explain their side of the story. Student mediators ask open questions using nonjudgmental phrases to get both parties to express what they would like to see happen and acknowledge what their options are. They have the choice not to talk to each other or to not be bothered by funny looks. The program continues to grow.

"That could be duplicated other places," Espy said.

Besides coming up with solutions, one goal of the summit is simply raising awareness of zero-tolerance policies.

"We've heard horror stories, some substantiated, some unsubstantiated, about students getting expelled just before state exams," Espy said. The implication is that schools tend to get rid of low-scoring students just before it's time for a major-stakes test. One anecdote she heard was about a boy who wore the wrong color socks.

Great Expectations

Every now and then, alumni from St. Joseph's Catholic School show up at Capital City Alternative School to visit their old campus. Before St. Joseph moved to Madison, the private Catholic school sat on the large campus not far from where Interstate 220 now crosses Medgar Evers Boulevard. The parochial school left in 1996, and Jackson Public Schools acquired the building and grounds.

Principal Marie Harris recently welcomed a couple of unexpected visitors—two former St. Joseph's students—who asked if they could look around their old school. Harris showed the old St. Joseph alums around. The quietness threw the visitors off.

"Where are the students?" One asked as they walked down the hall.

"They are in the classrooms," Harris told her.

"But it's so quiet!" The visitors looked at the shut doors in surprise.

Harris is proud of this. Expectations, discipline, order and routine result in busy children under her watchful eye. The students are quiet, neat and behaved. If they are not, imposing uniformed officers are only a few steps away.

Constant communication is key to the operation. "It's staying on top of things," Harris said.

Capital City Alternative School has about 200 students in grades 4 through 12 who have been suspended for 10 days or longer or expelled from Jackson Public Schools. The number of students varies from day to day, depending on who got suspended recently or who has returned to the home school. The average student stays for a semester. Those who are expelled will stay for one year.

In many ways, Capital City is not that different from Power Academic and Performing Arts Complex, one of JPS' star schools. Power APAC also serves grades 4-12. The students wear the same uniforms, study the same detailed lesson objectives, walk in the same silent lines. Expectations are posted in every hallway. School officials wait for students to arrive on the bus, get them in the building and keep a close watch on their every move from class to class. The difference is Power APAC is a school for academically and artistically gifted children.

The bottom line is that both schools put a heavy emphasis on strict control.

JPS administrators are frustrated that people think of Capital City Alternative School as a jail for children.

"It's a school!" Paula Van Every, director of the JPS Safe Schools-Healthy Students program, said. Both Capital City and Power APAC use "positive behavior intervention and supports," a structured flowchart of sorts that explains clearly what is expected of kids: Be ready, be respectful, be resilient. Van Every refers to it as a matrix.

The incentive system has rewards as well as negative consequences at Capital City. Every student gets a daily scorecard. If you forget yours at home, you get a new one for the day that's a different color so everyone knows you screwed up. Those students who accumulate 270 points for good behavior can participate in a group activity, such as a game of basketball. Students who earn more points can collect Bison Bucks, an in-school coupon that kids can use to get snacks, small toys or school supplies. (A bison is the school mascot.)

The goodies sit neatly in a large walk-in closet that serves as the store. Money from a federal Safe Schools Healthy Students grant pays for the items that the students work to "buy." In December, some students were saving up Bison Bucks to buy slightly larger items like a small tool kit and a kitchen rug. School officials said the students wanted to get those as presents for their parents.

The Jackson Free Press took a tour of Capital City Dec. 15. Officials did not allow the JFP to take any photographs or interview any students. Another stipulation was that the school staff couldn't discuss litigation involving handcuffing children.

It was the day after the nine-weeks tests, and many students were out during the JFP tour. Harris said that is typical the day before school lets out for a two-week Christmas break. The halls were wide, quiet and clean. Many uniformed JPS officers stood their posts on the hallway's shiny waxed floors.

Only three students were in a social studies class. All three were black boys. They watched a video on a Promethean Board, a chalkboard-sized smart board, about the conditions early English settlers encountered on a ship headed to Jamestown in colonial Virginia.

Back in the hallway, Harris explained that each classroom had five to nine computers for students. Peeking into a science class, she stressed the classes followed the same routine every day. She was irritated that one young teenage boy had his head on his desk and seemed to be asleep.

Capital City has the same academic objectives for each class, Harris said. This isn't a generic comment, it's a specific reference to the detailed curriculum outline schools must adhere to. In an exceptional education class, one student sat with his textbook open as two teachers hovered, one talking about the Panama Canal.

In a high school biology class, a teacher pointed to a formula on her whiteboard.

"How many atoms of sodium do I have?" She asked as her marker touched the notation NaClO3. The students will take the state biology test all students in Mississippi have to pass.

In Ms. Cunningham's social-sciences class, the lesson objective on the board stated, "Cite and analyze evidence of the political, economic and social changes in the U.S. that expanded democracy for minority and immigrant groups."

In a nearby language-arts classroom, directions on the board were specific. "Define and give an example: oxymoron, idiom, hyperbole, imagery." Harris explained this is a bell-ringer, a written activity students know to tackle as soon as class begins. Each class has a different bell-ringer every day.

The alternative school also has a courtyard with 12 square, raised garden beds. It has a leftover Catholic chapel that's been used for different functions, but this year is mainly empty. The cafeteria is cheery with student art. A gym doubles as a auditorium with a stage.

Harris bragged about students who did well at the reading fair, won essay contests or placed at the science fair.

Capital City has three full-time social workers, one school counselor, eight campus enforcement officers, one Crisis Prevention Institute trainer and two part-time, contractual mental-health therapists. School officials understand that parents work and might have transportation problems, so they try to find times when families can come in to discuss a student's academic and social needs.

"A lot of students want to be here," Harris said. "They get one-on-one attention. At their home school, they can get lost in the shuffle of a regular classroom."

Chained to the Railing

Williams sat for hours as an 8th grader handcuffed to the railing in the gym-auditorium. This is the same space St. Joseph alums dance at their reunions. Opposite from a stage are tall gym bleachers. Right in the middle of the bleacher section are four steps leading down to an exit door.

The paint on the metal railings along these few steps is chipped in places. This is where school police handcuffed and left many other students unattended for hours at different times over the years. The Southern Poverty Law Center is suing JPS on behalf of students who came forward with eerily similar stories. Williams, however, is not involved with the suit.

The students' allegations are stunning. They claim in the SPLC suit that school officers handcuffed them to the metal railing for not wearing a belt or for talking sass to a teacher. Some say they were forced to eat while handcuffed or not allowed to go to the bathroom. They allege they were left alone for hours.

A 14-year-old boy, who wore a stocking cap to class, supposedly threw his papers on the ground and refused to do his schoolwork. When school police left him cuffed to the railing, he yelled out because he had to go to the bathroom. The school safety officer refused to let him go. When the cuffs came off at the end of the school day, they left marks on his wrists. The 14-year-old showed this to a school official, who didn't get him medical attention. He got similar punishments repeatedly for wearing mismatched shoelaces and not bringing back paperwork.

One morning, a 15-year-old girl loudly called out the name of a friend in the hall to get her attention. A "campus enforcement officer" told her to "shut up." She talked back. "Who are you talking to? I ain't your child," she said. The officer walked the girl down the hall and handcuffed her to the railing.

Another time, a 14-year-old boy refused to take off his shoes during a routine search at the start of the day. The boy didn't want to do it and went to class upset. A school safety officer came to the boy's class and dragged him by his belt to the gym. The officer handcuffed his arm and leg and shackled the handcuffs to the pole. The boy said it was too tight. The officer didn't loosen the cuffs. A school official called his mom, but when she got to the school she wasn't allowed to go to him. The officer uncuffed the boy and brought him to the office to his mother. She immediately saw bruises and scratches on his wrist that he didn't have when he left for school that morning.

Yet another time, a different 15-year-old boy was dancing and rapping in his classroom. A school official came in the room and told him to stop. The boy stopped. "Boy, you look like you got an attitude," the school official allegedly said, then sent the student to the office. Two school security guards took the boy to the gym and handcuffed him to the stair railing. The cuffs left marks on his wrists.

Capital City Alternative School officials did not discuss allegations that security officers handcuffed students and left them alone for hours. This is because The Southern Poverty Law Center filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court June 8, claiming that JPS unconstitutionally punished students for minor offenses.

JPS attorneys released a statement earlier this year about the suit, saying the district would respond in an appropriate manner. "JPS is totally and fully committed to providing a safe learning environment for all of its students."

Williams is not part of this lawsuit, but he did appear before the JPS School Board in June. He had signed petitions asking the district to stop handcuffing students.

The district admitted in court papers that officers cuffed students to the railing.

On Jan. 5, the SPLC sent out a news release stating that it has asked a federal court to force JPS to turn over key documents describing the school system's practice of handcuffing alternative school students to a pole for hours at a time as punishment for minor infractions.

SPLC says the school district has failed to produce a single document from the handcuffing incidents.

"Jackson Public School officials have created a prison-like environment for alternative-school students by chaining them to poles and railings for minor, non-criminal violations of school rules," said Vanessa Carroll, lead attorney on the case for the SPLC, said in a statement. "Members of JPS staff and administration have testified that these documents exist, and we simply want the district to turn over this critical information."

School officials couldn't discuss the suit, but they did want to discuss what is changing at Capital City. In January, the school planned to start using a new software program that assesses student attitudes toward their individual infractions, consequences and interventions. Capital City also has bullying focus groups.

Students with emotional or mental-health issues are a challenge for any professional. The school district develops an individual education plan for each child in special ed (referred to in JPS as exceptional education) and seriously considers if a emotional or psychological disability causes misbehavior.

This spring semester and this summer, JPS plans more new programs related to the alternative school, Van Every said. One is called "Why Try," a violence-prevention program for secondary-school students. JPS will hold training and certification classes for Campus Enforcement Officers. Van Every said for adults who work with students, the district will also have phase II training through the Crisis Prevention Institute that teaches enhanced verbal skills and de-escalating angry individuals. The staff already gets training now on how to calm a child, how to come across as helpful and not threatening. Van Every explained it as constantly diffusing a conflict.

JPS officials say the security-resources officers—the official name for the uniformed school police—are not there to haul students off to jail. The intention is for these law-enforcement professionals to teach crime prevention, law-related classes and general lessons with the message, "Stay out of trouble."

JPS sees Capital City as a safe place without distractions. But the administrators recognize that negative influences remain in the child's community.

"What people tend to believe is these are bad children," Cheryl Lee, a social worker at Capital City, said. She shook her head at the generalization. "They've made bad choices."

Many students leave the alternative school and go on to succeed in life. Some have become hairdressers, mechanics, teachers and nurses.

"What people don't understand is that a child could have been defending himself," Van Every said. "Children get sucked into situations with a group. They make bad choices. It's part of growing up."

JPS officials cringe at the "cradle-to-pipeline" label. They think it's unfair and inaccurate. They see the alternative school as a way to help children succeed.

"This is a school. We support them. All behaviors have consequences," Lee said. "They were sent here for infractions. We didn't go out recruiting. This is not the pipeline."

"We do have parents that support us," Harris said. Two students at Capital City now are there because their parents requested it, she said. "Our children come here disgruntled. After they get acclimated, attitudes change."

Besides the alternative school, JPS houses its JROTC administrative offices at Capital City, as well as its GED program. JPS middle schools alternate using the campus football stadium for home games. St. Joseph's alumni still use the gym-auditorium for homecoming reunions.

"We have a lot of people coming and going," Harris said.

"It's not a prison out here."

Ground Zero

Betty Turner has a different view. She wiped down her kitchen counter after slipping two pecan pies in the oven. She works as a safety ambassador for Downtown Jackson Partners, and this day was a stressful one. Plus, she still had dinner to make and a kitchen to clean afterward. She beamed, though, when she showed off a framed picture of her 18-year-old daughter, Kantrisha. The girl is in 12th grade at Mississippi School for the Deaf and Blind and is concurrently taking two classes at Hinds Community College. Turner is proud. Her oldest child is an engineer in the Navy, and a picture of him in his dress-white uniform has a prominent space on the wall.

Turner is Drod Williams' mother, too. It has irritated her on end for years that JPS couldn't help her son, whom she suspects suffered from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder when he was younger. He had problems sitting still and being quiet. She's not at all happy that the school district did nothing to help Williams prepare for the military, and even did things that made it harder for him to enlist.

"It puts me back at ground zero," Turner says.

Jed Oppenheim, the senior advocate for the Southern Poverty Law Center in Mississippi, is familiar with the family's ordeal. He thinks Williams should have gotten the same attention his younger sister did with her disability. Her needs were perhaps more obvious.

"Here's a child with a visual handicap, something you can see," he said. Williams' disability wasn't as easily defined.

"Schools tend to push out children with emotional handicaps."

Williams and his mom said teachers and administrators at Wingfield High School definitely tried to push him out of school. He remembers when he was in 10th grade a teacher telling him, "Don't come back to my class."

"So, I didn't," Williams said, matter-of-factly. Of course, he got in trouble for skipping. It was a no-win scenario. He did spend time copying down dictionary pages verbatim during in-school suspension. That was not his idea. Recalling the incident when a teacher accused him of stealing her earphones, he still is indignant about the insult. "Teachers went in my pants," he said. "My money went on the floor." Two teachers searched him but didn't find the missing earphones.

His mom filed a complaint. She did that a lot during his school years. The principal didn't listen to her in this instance, Turner said.

One of the times that the school suspended Williams, she made a special point to make sure she brought him back to school on the 29th of the month, the day stipulated for his return on the official form. She got a call from the school before too long.

"If you don't come get him, he will be arrested and sent to the detention center," the school official on the line told her. "He can't come back until the 30th."

Turner tried to talk to the principal about the paperwork she had. "The principal wouldn't listen. He called me stupid," she said.

"I see why your son acts so stupid, because he gets it from his mother" is what Turner says the principal told her.

"I lost it," Turner recalled. She gave him her opinion, but later had to apologize in writing to get her son back in school. The principal still has not offered any regrets for his insult.

Zero Tolerance

JPS has a code of conduct that outlines specific behaviors the school district will not tolerate. Six classes of infractions outline misbehavior and possible consequences. It now includes the "expectations" language that Oppenheim says is a vast improvement over the rigid class violations. Much is still left to the principal's discretion, he says.

"The matrix has loopholes," he says.

If a principal decides a student is being disrespectful, he can classify the infraction as a serious violation or not.

"Being late for class or talking back could include disrespect," Oppenheim said. It's not unusual for students to behave like that, and discipline is required. But ever since the drug wars of the 1980s and the school shootings of the 1990s, politicians decided our children and teenagers were our enemies.

The school shootings at Columbine High School in Colorado and Pearl High School closer to home (and other schools) began a spree of laws and a general fear of our offspring. Most of the school shootings happened in suburban, white communities. Yet, as Oppenheim notes, it was the black and Hispanic kids in low-income areas who got the backlash of suspicion from adults. White kids also started getting suspended more. The strict policies were bad for all kids, but harsher for kids of color.

"Zero tolerance used to be just about drugs and guns," Oppenheim said. "Zero-tolerance polices are an overexertion of security measures. It's zero tolerance for kids to act their age."

The disparity in schools is huge. Many students go to class fearfully in an prison-like atmosphere. Oppenheim said fear itself can lead to even more behavior problems. "If I front you, you will front me back," he said, sticking his chest out.

"Schools are more surveillanced than any other part of the city," he added.

Russell Skiba, the Indiana researcher who has studied disparity in such school policies, links the popularity of school zero-tolerance stances to a U.S. Navy decision in 1983 to crack down on drug abusers in its ranks. 1983 was the same year the famous report, "A Nation at Risk," described the poor state of public education in the United States.

Three years later, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act. William Bennett, who was President Ronald Reagan's secretary of education and President George H.W. Bush's drug czar, asked Congress in May 1986 to withhold federal funding from schools unless they had zero-tolerance policies for drugs. He got little support, but more than one congressman liked the underlying message.

"We have to quit being bleeding hearts for every kid who is rotten to the core," Florida Rep. E. Clay Shaw said at the time.

In 1989, school districts in California, New York and Kentucky adopted zero-tolerance expulsion policies. The Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994 under President Bill Clinton's watch tied enforcement of school policies to federal funding, causing state Legislatures to require local school districts to implement zero tolerance regarding firearms, bombs or anything that might be considered a weapon.

The Gun-Free Schools Act did nothing to prevent five mass shootings at rural and suburban schools in 1997 and 1998. The shootings were all within eight months of each other.

The act also did not prevent the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School in Colorado. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 12 of their schoolmates and one teacher, then killed themselves. In 2000, a Michigan boy killed his 6-year-old classmate with a gun.

Knee-jerk reactions kicked into play all over the nation. Even as more schools enacted tougher policies to criminalize any dress-code violation or any type of disrespect, school violence actually had already started decreasing. While the school shootings of the late 1990s happened in white communities in white-on-white scenarios, it was black kids and other minorities politicians labeled as thugs or "super-predators," to use Bennett's phrase of choice. When predominantly white schools started searching students and implementing harsher discipline policies, they were only doing what had already been happening in minority and poor public schools for decades. Suddenly, school discipline was getting harsher for all kids.

In 2002, the No Child Left Behind Act began a decade of high-stakes accountability that tied the jobs of education administrators and teachers to the performance of scared children. "In fact, the problem in most cases is not the student, but, rather, the adults who react inappropriately to youthful behavior," the Advancement Project report stated.

The U.S. Department of Education projected almost 250,000 more students were suspended in the 2006-2007 school year than in 2002, the year NCLB became law. The number of expulsions during the same time rose 15 percent, even as youth violence had dropped dramatically since the crack epidemic of the mid-1980s and the school shootings of the next decade.

"The message sent by zero-tolerance policies is that education is not for everyone; rather, it is for those students who 'deserve' it," the report stated. It also notes the rise of school police departments and officers on campus: "Schools have become a growth industry for law enforcement, as there has been a massive increase in the police and security presence in schools."

The report discusses the suspensions for disrespecting authority, which usually just meant questioning a teacher. After the election of President Obama in November 2008, a school official paddled a black student in Calhoun City, Miss., for repeating the campaign slogan, "Yes We Can." In Pearl River County, Miss., school officials suspended a black student for two days for saying the president's name during lunch.

"The inescapable message is that schools and the police see even very young children as threats, as being unworthy of tolerance and understanding, or both," the Advancement Project report stated.

Real-World Cynicism

Williams has had some real-world lessons that leave him a little cynical. "Police ask you questions. If you answer, they tell you to shut up," he said.

He thinks he grew out of his ADHD or whatever kept him fidgeting and bugging impatient teachers. "I did talk a lot," he admits.

Williams doesn't think all his teachers are bad people. He remembers a counselor who helped him. He has fond memories of his Whitten Middle School science teacher who encouraged him to enter the homemade barometer project in the fair.

"Ms. Allen, she pushed me. We also had a cool principal, Mr. Greer," Williams said. He grins as he remembers. His smile widens as the subject changes to his plans for a weekend date. "I'm going to be with my girlfriend. We are going to the reservoir."

His plans to join the Navy got pushed back, but he still intends to enlist. Williams is taking classes at Hinds Community College this year to make it happen. If he has at least 15 college credits, the military will accept that in lieu of a high school diploma. He has to meet other qualifications, such as weight, no drug use and no criminal record. His mom is helping him clear his name on some of the old school-related charges.

Williams and his mom say JPS should have put him on a diploma-granting path in junior high instead of assuming he was a lost cause. If that had happened, he would have joined the military a year ago.

He sits back in a dining-room chair when an oven timer rings. His mom's pecan pies are done. He's a forward-looking young man, but he hasn't forgotten how zero-tolerance policies deferred his plans.

"Yeah," he says, shaking his head, "they pushed me out."

The Summit

The Children's Defense Fund Southern Regional Office is holding a statewide summit, "Dismantling the Cradle to Prison Pipeline," Jan. 21 at Jackson State University e-Center (1230 Raymond Road). The Southern Poverty Law Center, the NAACP and the American Civil Liberties Union are also participating.

Youth and adult workshops will tackle how zero-tolerance policies push children into the juvenile-justice system.

The summit is free to attend. Registration is at 8 a.m., and the all-day summit begins at 9 a.m.

For information, call Portia Espy at 601-321-1966, ext. 107.

What Works?

As pushback against zero-tolerance discipline increases, what are the alternatives?

• Peer mediation

• Case-by-case decisions

• Decreased police presence in schools

• Better training for teachers, administrators

• Smaller class sizes

• More parental involvement with students

• More community volunteers in schools

• Less stringent dress codes for students

• Defined expectations and consequences

• Creative outlets to allow children to express frustration and emotions

Costly Practice

A 2009 Justice Policy Institute report found that criminalizing children can be costly.

"Zero tolerance policies and more police in schools—policies intended to reduce school violence—have also increased the likelihood that an incident that previously would have been handled informally or by the school now results in arrest. This contributes to the clogging of an already overburdened juvenile justice system."

States spent about $5.7 billion in 2007 to imprison 64,558 youth committed to residential facilities, the report states.

In Mississippi during 2007, 219 youth were incarcerated at a cost of $426.51 a day each, or $93,405.69 a day for all of them. That comes to more than $34 million Mississippi spent that year to incarcerate kids.

A Problem with Curfews for Kids

Henry A. Giroux, a Pennsylvania State University researcher, says cities that enforce curfews and loitering bans might keep kids off the streets, but they also criminalize their behavior. "Zero-tolerance policies have been especially cruel in the treatment of juvenile offenders," Giroux wrote in a 2003 paper, "Racial Injustice and Disposable Youth in the Age of Zero Tolerance."

IDEA Doesn't Stop Discipline

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) outlines how schools can discipline students with disabilities.

Candace Cortiella, director of the nonprofit The Advocacy Institute, writes on the website Great Schools that schools can suspend or expel disabled students for conduct violations, but IDEA provides additional procedures.

Schools can make case-by-case basis decisions about discipline. "This provision provides flexibility for school personnel who are often operating within a district's 'zero-tolerance' policy," Cortiella writes.

She encourages parents to understand the school's code of conduct and to be the student's strongest advocate. Just because a child has an individual education plan, or IEP in education jargon, doesn't mean she won't get the same punishments as students without the specialized plan. IEP students can get in-school suspension, out of school suspension, or they can be sent to an alternative school.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.