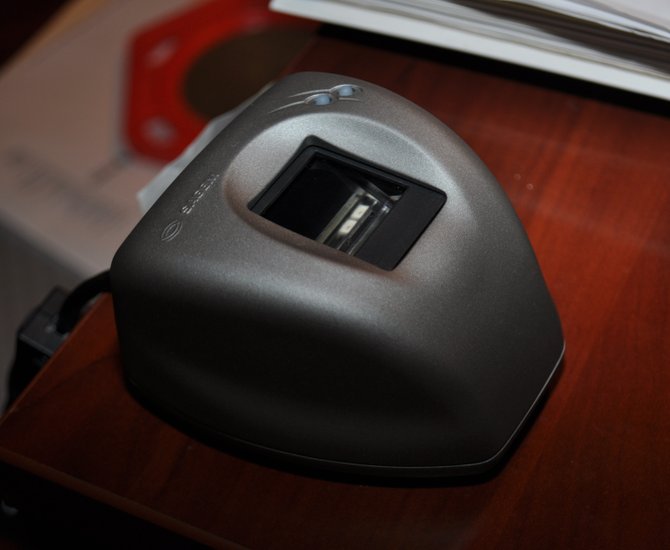

Parents and child-care providers have concerns about a new state program that requires a finger scan when picking up or dropping off kids at day care. Photo by Trip Burns.

Petra Kay is stuck behind the front counter at the Northtown Child Development Center, sitting in front of two computer screens. Because part of the center's mission is to help children from low-income families, Kay's more than 30 years of experience as an early childhood educator would probably better be spent writing grants to improve the center's service or working with the 110 children enrolled there.

Instead, she's filling in as the center's receptionist. Northtown is one of 20 child-care centers in central Mississippi taking part in a Mississippi Department of Human Services pilot program. DHS administers the state's child-care assistance, or certificate, program for poor families and pays providers like Kay who accept the certificates. Starting Sept. 4, parents and guardians of children receiving a subsidy must scan their finger when dropping off or picking a child up from day care.

In a letter dated July 31, 2012, Xerox assured child-care providers that the company would install the equipment at no cost. Included in the packet of information from Xerox was a provider agreement that said while the machines came at no cost, providers would be responsible for paying for any damage to the machines.

Kay and other child-care center operators say implementing the new system has been nothing short of nightmarish and that the problems are eating into revenues. Although DHS trained workers on how to use the machines, training parents is left up to the individual centers, meaning that a member of Kay's staff must remain on standby at all times to help people work the machine. Also, because the system relies on unique finger scans, staff members cannot override the system or check the kids in and out when parents forget. When that happens, providers might not get paid.

"It's a mess," Kay declares, with a hint of desperation in her voice as she demonstrates the equipment and online payment system.

Almost on cue, a woman in her early 20s wearing a white sweater and red T-shirt with bright green fingernails, bounces into the reception area and presses her colorful finger to a scanner sitting atop the counter because she'd forgotten to check in earlier.

Rosie Mack has grandchildren at Northtown but has not yet signed up for the finger-scanning program. It's inconvenient to drive across town to the DHS office on Medgar Evers Boulevard, which is outside her daily travel radius, she said.

"I drive on one tank of gas a week. Every mile counts," she said.

The concerns of Kay and Mack echo those of a number of providers across Mississippi who are not only frustrated about the buggy computer systems, but cite privacy concerns and say that piling on extra restrictions could force some parents to stop working to care for their kids at home. Providers and parents have lodged so many complaints about the system that Sen. Albert Butler, D-Port Gibson, chairman of the Senate Investigate State Officers Committee, scheduled a hearing to take place Oct. 10.

Carol Burnett, executive director of the Biloxi-based Low-Income Childcare Initiative, says she's talked to parents and providers who are worried about how DHS will use their personal information.

"They need (day care), and this service has been proven to have a huge difference for families. We need to make it easier for children to get into the program," Burnett said.

Burnett added the number of kids participating in the state's certificate program has already been cut in half in the past two years, and she worries that the new cumbersome scanning requirement will force some day-care centers to stop accepting certificates. Others could close their doors, she said. Currently, 8,050 children are on DHS' waiting list to get into the certificate program.

A recent Mississippi Economic Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census data found that Mississippi has the highest child poverty rate in the nation at 31.5 percent. Nationally, around 22 percent of children live in poverty.

"Programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and supports like child-care certificates play a critical role in keeping families afloat in a poor economy," wrote MEPC fellow Amarillys Rodriguez in the report.

Shirley Hampton, who co-owns Jamboree Child Development Center on Northside Drive, said the state should be investing more in early childhood education instead of "ridiculous programs" such as the biometric scanners.

"We want to be education centers not just baby sitters, but if you don't get rid of all these burdens, we're never going to get there," Hampton said.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus