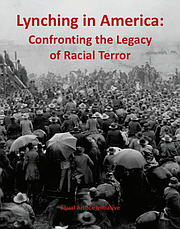

In total, EJI documented 3,959 lynchings of African Americans in twelve Southern states starting at the end of Reconstruction, in 1877, through 1950, which the organization estimates is approximately 700 more lynchings in these Southern states than ever reported. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

A chilling new report revealed this week reveals that racial terror lynching in the U.S. was much worse than previously believed.

Researchers from the Montgomery, Ala.-based Equal Justice Initiative spent four years throughout Deep South states where lynching was most prevalent—Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia —combing through local newspapers, historical archives and court records. EJI also interviewed local historians, survivors, and the families of victims.

“We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it,” said EJI Director Bryan Stevenson in a media release. “The geographic, political, economic, and social consequences of decades of terror lynchings can still be seen in many communities today and the damage created by lynching needs to be confronted and discussed. Only then can we meaningfully address the contemporary problems that are lynching’s legacy.”

In total, EJI documented 3,959 lynchings of African Americans in twelve Southern states starting at the end of Reconstruction, in 1877, through 1950, which the organization estimates is approximately 700 more lynchings in these Southern states than ever reported.

The report finds that Hinds County had the most lynchings of any county in Mississippi (22), which tied for 13th with Tangipahoa Parish, La. among the top lynching sites in the 12 states examined. Other Mississippi counties that made the Top 25 list included Lowndes, with 19; Kemper, Leflore and Warren counties had 18 each.

Overall, Mississippi had the second highest annual rate of lynchings per capita, of 0.55 per 100,000 each year until 1940. Florida had the most among the 12 states, of 0.59 per 100,000 people; North Carolina had the fewest, with 0.07 per 100,000 residents.

The report is even more astonishing when you consider that EJI focused on racial terror lynchings, which are distinct from "hangings and mob violence that followed some criminal trial process or that were committed against non-minorities without the threat of terror" and "were a crude form of punishment that did not have the features of terror lynchings directed at racial minorities who were being threatened and menaced in multiple ways."

Authors write: "We also distinguish 'terror lynchings from racial violence and hate crimes that were prosecuted as criminal acts. Although criminal prosecution for hate crimes was rare during the period we examine, such prosecutions ameliorated those acts of violence and racial animus. The lynchings we document were acts of terrorism because these murders were carried out with impunity, sometimes in broad daylight, often 'on the courthouse lawn.'

"These lynchings were not 'frontier justice,' because they generally took place in communities where there was a functioning criminal justice system that was deemed too good for African Americans. Terror lynchings were horrific acts of violence whose perpetrators were never held accountable. Indeed, some 'public spectacle lynchings' were attended by the entire white community and conducted as celebratory acts of racial control and domination.

Many of these were the result of African Americans violating social norms established by the white world. Among the lynchings that took place in Mississippi included:

• In 1889, in Aberdeen, Mississippi, a man named Keith Bowen allegedly tried to enter a room where three white women were sitting and although no further allegation was made against him, the "entire (white) neighborhood" lynched Bowen for his "offense."

• White men lynched Jeff Brown in 1916 in Cedarbluff, Mississippi, for accidentally bumping into a white girl as he ran to catch a train.

• In 1904, after Luther Holbert allegedly killed a local white landowner, he and a black woman believed to be his wife were captured by a mob and taken to Doddsville, Mississippi, to be lynched before hundreds of white spectators. Both victims were tied to a tree and forced to hold out their hands while members of the mob methodically chopped off their fingers and distributed them as souvenirs. Next, their ears were cut off. Mr. Holbert was then beaten so severely that his skull was fractured and one of his eyes was let hanging from its socket. Members of the mob used a large corkscrew to bore holes into the victims’ bodies and pull out large chunks of “quivering flesh,” after which both victims were thrown onto a raging fire and burned. The white men, women, and children present watched the horrific murders while enjoying deviled eggs, lemonade, and whiskey in a picnic-like atmosphere.

• In Hernando, Mississippi, in 1935, when white landowners learned that Reverend T. A. Allen was trying to start a sharecropper’s union among local impoverished and exploited black laborers, they formed a mob, seized him, shot him many times, and threw him into the Coldwater River.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.