Alonté Davis Anderson, a rising junior at Tougaloo College, has been sent to Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center three times. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

Alonté Davis Anderson, then 17, was riding his bike through his quiet west Jackson neighborhood one afternoon in November 2010. He had skipped school that day because he wasn't feeling well, and after his mother sent him to the corner store, he stopped for a quick smoke break.

Just a few minutes earlier, his neighbor's home had been broken into, and as police responded to the call, they noticed him riding down the street. The Jackson cop car passed him, and then turned around and approached him.

"Where you been?" one of the Jackson police officers asked him.

"Nowhere," he responded. "I'm finna go home."

"OK, get in the car."

Luckily, his neighbor got a clear look at the break-in suspects before they bolted, and though Anderson was two inches shorter and nearly 20 pounds lighter than the stats she'd listed on the police report, he was still taken into custody for questioning on suspicion of house burglary, an offense that could have easily landed him at the Raymond Detention Facility.

The neighbor came to his defense almost immediately, visiting his mother and going up to the jail, but Anderson still spent three days at the Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center—terrified that this time he might not get out as easy as the previous two times he had been in there.

This would be the last of his three trips to the juvenile detention center, and though he spent a combined total of three weeks there, he still remembers each trip vividly and having the same thought each time: "If God lets me go home, I'll do right."

Seeking Independence

It is pouring down rain outside as Anderson stretches out in his mother's living room in west Jackson on a recent Friday afternoon. He sits, with his legs sprawled out in front of him, twisting his dreadlocks around his pointer finger. Anderson, now 21, is pensive and precise with his words as he tells the story of his experiences at the detention center. His high-school awards are stacked on the coffee table, and in the corner rests piles of beauty tools and hair products.

His mother, who did not want to be named for this story, just graduated from cosmetology school.

"The first time I went, I was like, 'I'm in jail,'" Anderson said, rubbing his arm as he stared out the window. There was finally a gap in the rain. "I didn't consider it the detention center, 'cause I didn't know what to expect, but when I got there, I think I'm kinda resilient, so it really didn't faze me."

When Anderson was 16, like most teenagers, he sought independence and barely tolerated any scolding from his mother. The oldest of four, he shied away from chores such as cleaning his room and washing the dishes. One day, after a small argument with his mother, Anderson had enough and decided to leave it all behind and left for a couple of days.

Once he returned home, he and his mother had another argument and by the time they were done, the police were at his door, Anderson said. He then spent three days at Henley-Young in south Jackson.

The first time Anderson got to Henley-Young, he had to take a computerized mental-health exam that asked him questions like "Have you ever seen someone die?" "Do you smoke cigarettes?" "How many times a day do you go to school?" "How many times a week do you go to school?" "Are you suicidal?"

After the computer test, nurses asked him probing questions about drug usage, personal medications, allergies and ailments. Anderson said a drug test is mandatory every time a minor goes to the detention center. Then he had to put on an orange jumpsuit, with "Juvenile" emblazoned in large black letters across the back.

Anderson said that being in Henley-Young motivated him to never go back because he was so used to being independent. He recalls being hungry a lot inside Henley-Young and disliked not being able to do simple things like grab food from his fridge. Instead he had to ask the guards for permission to do anything, which made him feel like a grown criminal, he said.

The daily schedule stuck as close to a normal school schedule as possible, with breakfast hour, class time, then a short recreational period after lunch.

Afterward, the kids were taken back to their pods where they would sit and entertain themselves until dinner. They usually ate in their cells and were allowed to enjoy a movie and a light snack before bed. Bedtime was usually around 8 or 9, Anderson said.

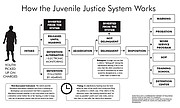

This was in 2010, however, and Hinds County was sued for the treatment of youth in Henley-Young the following year in summer 2011. The detention center has been under a settlement agreement since March 28, 2012, pending improvement on conditions in the facility from staffing to mental health care.

The initial lawsuit from 2011 detailed scenarios of maltreatment inside Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center.

"Henley-Young staff torment youth—including those living with mental illness—with taunts and threats that constitute verbal abuse," the 2011 complaint says.

Things are improving and better than they were in 2012, however, court monitor Leonard Dixon says. Dixon, who is based in Missouri, comes to Henley-Young regularly and submits annual reports to the court in the case. One of the biggest improvements Henley-Young has seen recently is an increase in staffing and a stable administration, Dixon says.

"I think they have a better understanding of where we are trying to go, and I think having the right person in charge now (Johnnie McDaniels), you also have the support of the board of supervisors and the county administrator—everybody is together now," Dixon told the Jackson Free Press.

While Henley-Young has made improvements (13 of the specific provisions from the 2012 settlement agreement have been resolved), Dixon's January 2016 report shows that the detention center is "non-compliant" with 26 of the 71 provisions he measured.

Henley-Young did not have mental health or substance-abuse treatment plans for youth as of January 2016, the court monitor's report says.

Dixon says Henley-Young's progress is better than other detention centers he has worked with, and that changing the culture takes time.

"A lot of places I've worked with haven't moved as far, and it's not one of these things that it's done overnight because if that's the case, you wouldn't have to be there for a while," he said.

A Separate Labyrinth

It's easy to see a mugshot of a young person, apprehended and maybe locked up for doing something wrong, and think we are safer while imagining a brighter future where crime and blight do not intrude into daily life.

But many juvenile "offenders" are routinely sent into a separate labyrinth from adult offenders in the justice system, one with its own complex problems, remedies and slowly changing standards.

In Mississippi, if a child commits a "status offense," like habitual disobedience to a parent, running away or truancy: something that would not be considered a crime if committed by an adult, he is sent to youth court. If a child commits an act that would be designated as a crime if she were an adult, she is also sent to youth court, for what would be considered a delinquent act.

Children can still be tried as adults and be sent to circuit court instead of youth court, however, if they commit acts punishable under state or federal law by life imprisonment or death (like murder or armed robbery) or for use of a concealed deadly weapon, shotgun or rifle, which is a felony.

The system is inconsistent, though, and provides anything but equal protection or punishment of young offenders. All counties have youth court, but not all youth courts in the state have access to the same detention alternatives, unless they want to pay for those alternatives, in which case they send kids to other counties' detention centers. Some counties in the state have several alternatives to detention, while others have few options.

Anderson says he didn't have any option other than going straight to Henley-Young. His first trip to the detention center lasted three days, while the second (for disturbing the family peace) lasted a week and a half. His third experience was unique and could have ended a myriad of ways.

Under Mississippi law and youth court rules, the initial delinquency youth-court hearing process can take no longer than 90 days from when the youth court prosecutor files the petition in a child's case.

Youth court is a bit different than circuit court. There is no jury in youth court, and the child has legal representation. The youth-court prosecutor represents the state. A child can be let off at almost any point in the process, if a judge determines that the child is not "delinquent."

Children placed in detention centers at intake have a right to a detention hearing within 48 hours of their intake (excluding weekends and holidays). At detention hearings, judges look at the probable cause, or the likelihood, that a youth committed the offense they are charged for.

For Anderson, seeing his neighbor in his detention hearing changed his trajectory for the better—pulling an innocent minor out of the system. He said he was happy to see her in the courtroom because he thought he was going to have to stay in the detention center even longer.

"I thought they was going to try and say I did it," Anderson said. "There was three people who broke into that house, and they only caught me or only picked me up—and I am not going to say 'caught' because I didn't do it—because I was going to say, dang what are you going to do about the other two people, you all are just going to be satisfied with catching me?'"

Anderson's neighbor eased his worries.

"She was there (and said), 'That wasn't the dude who broke into my house,'" Anderson said.

If Anderson's neighbor was not there, and the judge thought that it was more likely than not that he did commit the crime, the judge would then determine whether or not he should still be held in the detention center. Regardless of whether he stayed or not, the youth court prosecutor would then file a petition.

After the youth-court prosecutor files a petition against the child, the judge will hold an adjudication hearing. It's at this hearing that the child is formally charged and found "delinquent" or not.

If a youth admits to charges or is charged at the end of an adjudication hearing, he or she is declared a "delinquent" child not "guilty," although the definitions are arguably the same.

A "delinquent" child, Mississippi law states, is a child who is 10 years old and has committed an act that would be designated as a crime if he was an adult. The judge makes the final decision as to whether or not the kids committed the alleged crimes.

If a child is found delinquent, then she goes to a disposition hearing, where judges can use a broad range of consequences to—in an ideal world—help alter and change the youth's behavior and prevent him or her from offending again, thus keeping the child out of the system permanently.

Consequences range from counseling with probation to enrollment in Oakley Youth Development Center, the state's training school. Some counties have access to the range of consequences: warning, probation, counseling, adolescent opportunity programs, Oakley Workforce Development and detention centers.

But with a loss of federal funding looming this July, potentially leaving the juvenile-detention system in an even more challenging place, especially since sending young people facilities like Henley-Young make them even more likely to commit a crime.

Over-using Detention

Juvenile detention usually leads to worse outcomes for youth in the future, exacerbated by the number of times and lengths of stays there. Young people placed in pretrial detention are much more likely to be charged, found delinquent and sent back to detention centers versus their peers who are kept at home before their court hearings, a 2012 University of Central Florida study found.

Armed with more data, the Annie E. Casey Foundation launched the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative—or JDAI—back in the 1990s, and it has expanded to 39 states since then. A University of California at Berkeley Law School analysis found that detention populations have fallen more in sites that use JDAI than states' averages. Mississippi has been a JDAI site since 2008, but changes to the state's juvenile-justice system take time.

Mississippi's JDAI initiative consists of a statewide task force that meets quarterly with judges, mental-health providers, MDHS workers and detention officers throughout the state. The group has been working to implement alternative policies, practices and options for youth courts around the state.

There are five counties in the state considered JDAI sites: Adams, Harrison, Leflore, Rankin and Washington. Representatives from these counties meet regularly to discuss how their alternatives are working.

The JDAI task force and initiative were products of a 2012 law that authorized a group of public employees to develop a plan to change juvenile justice in Mississippi. The task force presented its findings in November 2013 to the Legislature, and things have been slowly changing ever since. Jurist in Residence Judge John Hudson is overseeing the state's youth courts and is one of the leaders in the state's JDAI initiative.

A key JDAI initiative involves a pre-assessment tool that every youth court across the state could use to keep kids out of the detention center when they are first picked up at intake. It's called the Risk Assessment Instrument, and right now the state's JDAI task force is working to take the tool statewide. The risk-assessment tool is supposed to objectively evaluate whether or not a kid needs to be held in a detention center while waiting for his or her hearing, Hudson said.

The tool measures what the charge is, a young person's history with the youth court, what the circumstances were surrounding the arrest or intake and any aggravating or mitigating circumstances in a child's life. The tool gives the child a score, and only if it's above a certain point does he or she need to be detained.

The purpose behind the RAI is that you put the right kids in the right detention centers for the right reasons," Hudson said. "It gives you some cover for your decisions and takes away from the gut reaction as well ... you don't want to put a kid in there because he's pissed a judge off or pissed a police officer off."

More than 300 counties across the country have implemented the tool, said Stephanie Vetter, a senior JDAI consultant working directly with the Mississippi JDAI task force. 93 percent of JDAI sites throughout the country show improvements in public safety outcomes, the 2014 JDAI progress report says.

"None of the places that have reduced their detention populations have seen an increase in crime. It allows people to make more objective decisions," Vetter said.

Research and history show that the country has over-used detention, Vetter says, and research shows that youth who are detained or incarcerated have much higher rates for illicit drug and alcohol use, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health report from 2004 says.

"In all of the JDAI sites, not only do detention populations go down safely, their state training schools and prison placements also go down about the same percentage," Vetter said. "Those populations are reduced by (about) 43 percent because we are funneling only the right kids into the system versus widening the net."

Revolving Door Ahead?

Beyond the pre-screening tool, JDAI also seeks to offer alternatives for judges to monitor youth pre-adjudication like having electronic monitoring with house arrest (with an ankle bracelet), an evening reporting center or a short-term shelter.

Vetter says alternatives have to be in place because it doesn't make sense to have a pre-screening tool that says "this child doesn't need to go to the detention center to wait for his trial," but then have no other place to send him.

"You have to have a detention alternative in order for this whole thing to work," she said.

In Mississippi about five counties now are able to use some or one of these alternatives. JDAI also helps states save money. Detention alternatives cost much less than housing a child at a detention center, because detention centers are around-the-clock facilities where personnel have to monitor kids 24/7. Electronic monitoring with house arrest, however, costs $4 per day, JDAI research shows.

Adams County, where Judge Hudson used to preside as the youth-court judge, has electronic monitoring, which keeps kids out of detention centers before their adjudication. Judge Walt Brown, the new youth court judge there, says that even with the monitoring device as an option, AOP was the best option for youth, especially those with more serious offenses.

"When I had the children who were first-time felony offenders without violence and that sort of thing, AOP is the perfect place for those people to go," Brown said. "They were reporting four days a week—it kept them off the streets, and they had a lot more hands on one-on-one communication with counselors."

AOPs are year-long, structured after-school programs that pair youth with counselors who not only help them with homework and schoolwork but also provide behavioral and emotional therapy and counseling if needed. AOPs are designed to be "pre-intervention" programs.

The threat of going to Oakley is the "hammer" judges use to enforce positive behavior and outcomes up the food-chain—before they have to send kids to the training school.

Several of the state's AOPs, though, are closing down due to the lack of funding. The federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families currently funds Mississippi's AOPs, but the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced last October that the use of TANF money for the AOPs violates the Social Security Act and "cannot be used to provide juvenile justice services."

As a result, the state's AOPs will lose federal funding July 1. The Mississippi Department of Human Services now administers TANF funds to the AOPs. The department said in a statement that "without funding for the programs we are left with little choice but to close all AOPs. MDHS, along with our partners at the court and AOPs, will continue to search for additional funding from other sources."

On the whole, Mississippi's juvenile-justice system was ahead of the curve at one point with the wide implementation of AOP programs across the state.

Now there are only 18 AOPs statewide that serve multiple counties each.

Hudson said when it comes to juvenile-detention alternatives, AOPs were the alternative that so many youth-court judges relied on for years. Hudson said AOPs were like a diversion program before training school for kids that committed more serious crimes.

"AOP kids were the more serious kids that you thought you could maintain in the community, where if they didn't do the AOP program, their next ticket were the training schools," he told the Jackson Free Press.

With the closure of AOPs around the state, Hudson said judges will be forced to send kids one of two directions: to probation and counseling services that are less stringent than year-long AOP programs or Oakley Youth Development Program, which held an average population of 67 kids in 2015, the MDHS annual report shows.

The average length of stay for a felony offense is 20 weeks. Only youth who have committed a felony can be admitted to Oakley, currently, and the recidivism rate is 22 percent.

Without AOPs, judges will have to send more kids to Oakley. More kids means kids will leave quicker and likely return, or as Hudson puts it: "the front door dictates the back door."

"Keeping a child in Oakley costs a heck of a lot more than keeping a child in a community-based program, but now with AOPs going by the wayside, Oakley is going to be under pressure," Hudson said.

Not Like Adult Prison

The Mississippi Legislature has been slow to pick up the proposed changes to the juvenile-justice system (the task force report to the Legislature was published in late 2013)—until this year when the Legislature passed the Mississippi Juvenile Detention Facilities Licensing Act.

The act enacts and ramps up standards necessary for juvenile-detention centers in the state to operate and were based on recommendations from the governor's task force on juvenile-detention alternatives.

Sen. Brice Wiggins, R-Pascagoula, was the principal author of Senate Bill 2364. Wiggins, who has worked as a youth court prosecutor, said the bill was necessary because not all juvenile-detention centers across the state are at best-practice standards.

"We're dealing with kids in these situations from (ages) 9 up until 17, and they are different (than adults), not saying this to make up for what they've done, but their brains, bodies and maturity levels are different than adults so what you do for adults is not what you need to do for juveniles," Wiggins told the Jackson Free Press.

"We want to make sure they are getting the proper oversight so that they don't become offenders in the adult system. When I was a prosecutor in the youth court and then in the DA's office, I saw some of the same people (kids) come up through the adult system. The centers need to understand that this isn't like adult prison, they're juveniles."

The bill, which was signed into law in May, tightens requirements for the state's juvenile-detention facilities by expanding and clarifying definitions in youth-court law. For example, the word "assessment" (something all juvenile-detention centers are supposed to do when a kid is admitted) is now defined as an examination "to determine the child's psychosocial needs and problems, including the type and extent of any mental health, substance abuse or co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders and recommendations for treatment."

Wiggins said the idea behind licensing detention centers is to bring consistency across the state's centers and raise standards is to get to the kids early with "proper resources and standards so they don't graduate to the adult system."

"People (need) to understand that they're not adults. I don't want to sound like I'm going easy, I'm not, it's just, you know, once you're in the system, you're not the same, and we need to recognize the resources that they need particularly in mental health," Wiggins said.

Wiggins, who is vice-chairman of the Senate Public Health Committee, said that mental health is an issue for adults in the state, and that by addressing those issues early in juveniles, hopefully we can stop or address those issues on the back end.

Senate Bill 2364 authorizes the state's licensing agency to conduct mock reviews of all juvenile-detention facilities statewide starting Oct. 1.

Detention centers will have time to come into compliance, but the deadline for that process will be sometime next year. Detention centers will need to come into compliance or shut their doors.

With the new law taking effect and the state's push to find alternatives to detention even before kids have a trial, a possible implication is that some juvenile-detention centers might have to close sections in coming years, which Vetter says can be pre-planned in order to move detention money to other alternatives.

"Mississippi will have to get busy developing a state-level strategy; it's not a cookie-cutter approach, but the state does provide certain services to this population, (and) they have some responsibility," Vetter said.

"And then locally, this is a tough piece, you've got to get your county commissioners behind the idea of reinvesting the money that's been tied up in these facilities and getting them to plan ahead, in all of our JDAI sites, we've never had a staff laid off because everybody has been able to plan ahead."

'Almost Like Preparation'

Anderson is now a rising junior at Tougaloo College and said that he one day wants to be governor. He is studying sociology and has stayed out of trouble since his last trip to Henley-Young. "I'm more focused on things locally because I just feel like I've got to help my people and my city and my area first," he said.

"Then, hopefully, they'll be rejoicing about all the things I did for them, and then maybe I can spread out and be a senator or a congressman."

He said that having an alternative to detention could have helped with the juvenile-detention rate, as well as his own personal perception of Henley-Young. He describes his views of the court system he experienced as "lackadaisical," and said that he felt as though he was expected to know how the court system operated.

"They try to keep it as uncomfortable as they can so you don't come back," he said.

Anderson says his experience in the detention center felt like society's way of preparing him and those with him for their futures in the juvenile-justice system.

"For me, I feel like it's almost like preparation, it feels like (people think) these kids are bad, let's prepare them, like junior high, like junior jail," he said. "It's just like they put you in your cell, they do the bare minimum that they are required to do by the state law, and they just release you with the hopes that you come back so they can continue making money so this business can thrive like any other business."

"I feel like as long as jail is looked at as a business and ran as a business, nothing's going to change."

This is Part 1 in a new series on juvenile detention in Mississippi supported by a Solutions Journalism Network grant. It is also an installment in the JFP's ongoing series on "Preventing Violence," which is at jfp.ms/preventingviolence. Email Arielle Dreher at arielle@jacksonfreepress.com and Maya Miller at maya@jacksonfreepress.com.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.