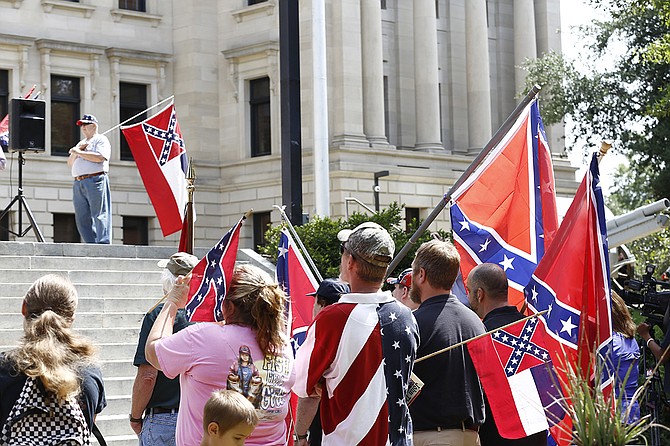

Mississippians supporting the state flag rallied outside the Capitol a month after Dylann Roof, a white supremacist, murdered nine African Americans in South Carolina. Investigators found pictures of him holding a rebel flag. Photo by Imani Khayyam.

JACKSON — Pressure to change the Mississippi state flag has intensified since shocking images emerged of torch-wielding white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va., marching to protect symbols honoring the Confederacy—a weekend rally that ended with an anti-racist protester dead.

The state now has the distinction of being the only one that still contains the most prominent Confederate symbol embedded inside its official flag.

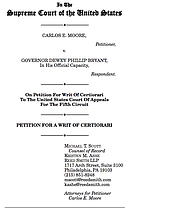

So far, with the reluctance of most Republican state leaders to touch the third rail of southern politics—Confederate memorials—it seems the only possible avenue to change the state flag is through the judicial system. That may not be as far-fetched as it once seemed, though, with the U.S. Supreme Court recently asking Gov. Phil Bryant to respond to attorney Carlos Moore's petition to the high court to hear his lawsuit against the state flag.

Mississippi Flag: A Symbol of Hate or Reconciliation?

The Mississippi Sons of Confederate Veterans are fighting hard to keep the state flag to honor the Confederacy. Others are fighting back.

Facts about Mississippi, Secession, Slavery and the Confederacy

The JFP’s archives of historically factual stories about slavery, secession and the Civil War in Mississippi, with lots of links to primary documents.

Moore asserts that the flag is unconstitutional and hateful government speech, violating his Equal Protection rights under the 14th Amendment.

Both U.S. District and 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals judges have ruled that Moore does not have standing to bring his case against the governor because he cannot prove injury.

The attorney then filed a petition for the U.S. Supreme Court to hear his case earlier this summer. The high court easily could have thrown out Moore's petition but instead has asked the state to respond.

'It's a Good Sign'

Michael Scott, who represents Moore in the case, said the fact that the high court asked for the state's response is a good sign. They get around 8,000 petitions a year, Scott said, and usually only grant between 80 and 100 of them.

"If the court is not interested in the petition, they would just deny it; if they are interested and might be thinking about granting it, then they will invite the other side to reply, so that's what's happened ... it's a good sign," Scott told the Jackson Free Press.

Taxpayer dollars are paying for lawyers in the attorney general's office to defend the governor in the lawsuit. The State has until Sept. 28 to file a response to Moore's petition.

In October, the high court will likely decide whether or not to grant Moore's petition and hear the case in full, meaning both sides will file more legal briefs and possibly have oral arguments. If the court grants Moore's petition in October, Scott said, the court could have a decision in the case by next summer.

The U.S. Supreme Court is only deciding now whether or not Moore has standing to bring his lawsuit against the governor. If the court grants his petition and then eventually rules in Moore's favor, his case will return to Jackson for trial, but if they rule against him, the suit will officially end.

The 5th Circuit used the Establishment Clause to argue that Moore did not have standing in the case, which Scott disagrees with.

"It is well-established that the State cannot say 'we like Catholics better than Protestants.' ... The state cannot do that, and we think this is no different," Scott said. "If they cannot express that view as to religious preference whether symbolically or literally, ... we think it ought to be just as clear that a state cannot implicitly, symbolically endorse white supremacy, which is what we say the flag does."

It's been more than two years since Dylann Roof, a white supremacist, murdered nine African American churchgoers at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina.

Lawmakers there voted to take down the Beauregard banner, which flew outside their statehouse.

What the Flag Represents

The Beauregard banner was used to differentiate the Confederate troops from Union troops during the Civil War, which southerners started after seceding to fight for the right to continue slavery and to force "free states" to allow it and return runaway slaves, as Mississippi's Declaration of Secession explained.

It was also the primary battle flag of Gen. Robert E. Lee in northern Virginia, and three well-known Mississippi brigades fought under it before the south lost the war. After Reconstruction ended, Mississippi lawmakers voted in 1894 to adopt a new state flag with the Beauregard banner in the canton corner.

Following the South Carolina massacre, House Speaker Philip Gunn, R-Clinton, spoke out against the state flag in July 2015 at the Neshoba County Fair, where it is popular. He was greeted with protesters waving their banners.

Mississippians in both camps—pro- and anti-state flag—filed ballot initiatives with the secretary of state's office in 2015, so citizens could settle the matter at the voting booth, but neither made the ballot. That summer, state flag supporters and protesters held rallies at the Capitol. In October, hundreds of people marched on the Capitol in support of changing the state flag.

Mississippi Flag: A Symbol of Hate or Reconciliation?

The Mississippi Sons of Confederate Veterans are fighting hard to keep the state flag to honor the Confederacy. Others are fighting back.

As soon as the Legislature convened for its 2016 session, however, state flag supporters converged on the Capitol, too. No bills filed to change the state flag made it out of committee, and days later Gov. Bryant quietly declared April "Confederate Heritage Month."

Days later, attorney Carlos Moore sued Bryant over the state flag.

Tensions grew. Alternative flag designs circulated. The Mississippi Legislative Black Caucus made continuous calls to change the state flag, which continued to fall on deaf ears. Bryant and Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves maintained their stances that only the voters, not legislators, should change the state flag. The 2016 session closed with no change.

All the state's public universities still flying the state flag took matters into their own hands and furled the banner throughout the summer.

In September 2016, U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves ruled in the governor's favor. He wrote that while "persons who have engaged in racial oppression have draped themselves in that (Confederate) banner while carrying out their mission to intimidate or do harm," Moore had not proved standing to make his case against the state flag.

The 'Blood and Soil' Era

In November 2016, predominantly white Americans elected Donald Trump to the presidency. In the 2017 Mississippi legislative session, amendments to force state universities to fly the state flag seemed to garner more support from white lawmakers than bills to change it. In March, the 5th Circuit affirmed Judge Reeves' decision in Moore's case; in May, New Orleans began to take down its Confederate monuments.

In response, Rep. Karl Oliver, R-Winona, called for the "lynching" of anyone who removed those monuments. He still occupies his seat (just not his vice-chairmanship) today. In June, Moore appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court with his case against the governor—and the state flag.

On Aug. 12, 2017, white supremacists rallied in Charlottesville, Va., in support of the Robert E. Lee statue that was set to come down, with chants like "You will not replace us!" and "Blood and soil!" The protest turned into a deadly demonstration after a young white supremacist drove his car into counter-protesters, killing anti-racism activist Heather Heyer.

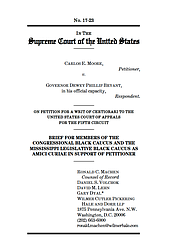

Moore's petition gained some national traction in the meantime, as several prominent Congressional Black Caucus members including civil-rights veteran John Lewis, D-Ga., and the queen of reclaiming time, Maxine Waters, D-Calif., signed on to an amicus brief.

"Ending government endorsements of racism is essential to our nation's continued progress toward ending racism itself. This Court should grant certiorari to reaffirm the Constitution's protections against state-sponsored messages asserting the second-class status of a race," their brief says.

Scott said he believes the amicus briefs filed in the case help the court decide whether or not to grant a petition.

"Given the fact that (the Supreme Court) can only take a small percentage of cases, like 1 percent, the court looks for indicia that the issues are important not just to the litigants in this case but are important to a broader spectrum of people, and that's what the amicus briefs helped convey," he said.

Over the weekend, another prominent state Republican came out in favor of changing the flag. Andy Taggart, a long-time Mississippi Republican, released a statement calling for the flag to be changed. "I ask that Mississippi Republican legislators declare their intention to lead in the 2018 Regular Session of the Legislature by co-authoring and pre-filing bills this fall to strike the Confederate battle flag by statute," he wrote. "And I ask that our Republican statewide elected officials and at all levels of government stand in favor of making this extremely important change for the future of our state."

Taggart had served as chief of staff for Gov. Kirk Fordice, who had spoken to the Council of Conservative Citizens, the group that later inspired Dylann Roof's rampage. Fordice told the AP in 1999 that it was just politically correct to "demonize" the CofCC and that accusations of its racism was "hearsay."

"There are some very good people in there with some very good ideas," Fordice said then of the CofCC.

Email state reporter Arielle Dreher at [email protected]. Read more about the state flag jfp.ms/slavery.