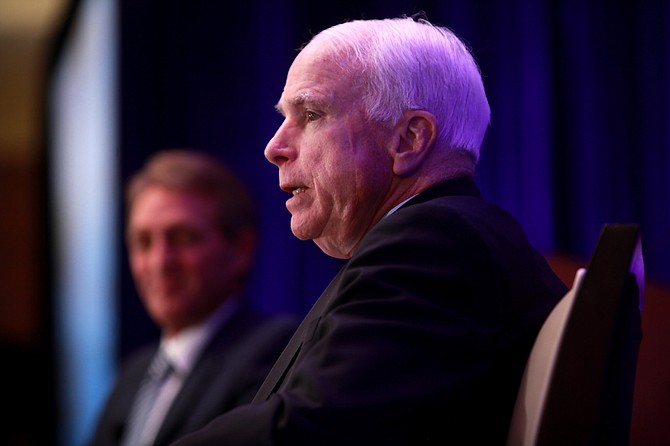

Sen. John McCain's diagnosis of brain cancer jolted the Senate where Republicans and Democrats offered prayers and words of encouragement for a six-term lawmaker with a war hero past. Photo courtesy Flickr/Gage Skidmore

Arizona U.S. Sen. John McCain, who died Saturday, Aug. 25, of brain cancer at age 81, once apologized for lying to voters about his position on the Confederate flag.

In January 2000, as McCain battled George W. Bush in the Republican presidential primary, a CBS reporter asked McCain if he believed the Confederate flag should continue to fly over the South Carolina statehouse.

“The Confederate flag is offensive in many, many ways, as we all know,” McCain replied. “It's a symbol of racism and slavery. But I also understand how others do not view it in that fashion. My forebears from Mississippi fought under the Confederate flag. They were not slave owners, and I’m sure they considered their service—one I believe died in Shiloh—noble.”

With the South Carolina primary a month away, McCain’s aides panicked; calling the flag “a symbol of racism and slavery” was anathema to the white primary electorate there. For the rest of the campaign, McCain answered the question differently: It’s “a symbol of heritage,” McCain said as he read from a piece of paper the next day, using language amenable to Civil War revisionists who falsely claim that southern states did not secede and enter the Civil War to preserve and extend slavery. Like his rival, Bush, McCain said the people of South Carolina should decide the fate of the flag.

Confederates Speak

In their own words, Confederate leaders explain secession, the Civil War and their views about black people.

McCain led in early polls of the state, but the flag flap—combined with a smear campaign attributed to Bush strategist Karl Rove that falsely claimed McCain fathered a black child out of wedlock—likely cost him the South Carolina primary and, with it, the Republican nomination.

Two months later, McCain returned to Columbia, S.C., where he apologized for putting political interests ahead of candor.

‘The Wrong Side of American History’

“I feared that if I answered honestly, I could not win the South Carolina primary,” the Arizona senator who named his campaign bus "The Straight Talk Express," said at a luncheon in the state’s capital city. “So I chose to compromise my principles. I broke my promise to always tell the truth.”

His Confederate forefathers in Mississippi, McCain said, “fought on the wrong side of American history.”

“I don't believe their service, however distinguished, needs to be commemorated in a way that offends, that deeply hurts, people whose ancestors were once denied their freedom by my ancestors,” he continued.

McCain said he did not seek absolution for lying to voters because “honesty is easy after the fact when my own interests are no longer involved.”

In a 2002 memoir, McCain opened up more about that period in the campaign.

“By the time I was asked the question the fourth or fifth time, I could have delivered the response from memory,” McCain wrote. “But I persisted with the theatrics of unfolding the paper and reading it as if I were making a hostage statement. I wanted to telegraph to reporters that I really didn’t mean to suggest I supported flying the flag, but political imperatives required a little evasiveness on my part. I wanted them to think me still an honest man, who simply had to cut a corner a little here and there so that I could go on to be an honest president.

“I think that made the offense worse. Acknowledging my dishonesty with a wink didn’t make it less a lie. It compounded the offense by revealing how willful it had been. You either have the guts to tell the truth or you don’t. You don’t get any dispensation for lying in a way that suggests your dishonesty.”

The Confederate battle flag continued to fly on the South Carolina statehouse grounds for another 15 years, coming down only after a neo-Confederate gunman massacred nine black churchgoers at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, and a photo emerged of him holding the Confederate flag. The killings sparked debate over Confederate symbols across the country, including in Mississippi, where U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker and then-U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran joined Philip Gunn, the speaker of the state House of Representatives, in calling for a new state flag without the Confederate imagery of the current one despite the continued support of the Mississippi flag by many residents.

The Black McCains and the White McCains

McCain’s father, John S. McCain Sr., hails from Carroll County, Miss., where he was born the son of a plantation owner. Days before the 2000 South Carolina primary, McCain learned he was wrong when he said his ancestors did not own slaves; “I didn’t know that,” McCain told reporters from Salon, moments after they handed him documents showing his great-great-grandfather owned at least 52 slaves.

“I guess when you really think about it logically, it shouldn't be a surprise,” McCain said. “They had a plantation, and they fought in the Civil War, so I guess it makes sense.”

Eight years later during the 2008 presidential race, Lillie McCain, a black professor of psychology who lived in Flint, Mich., at the time, told national outlets she had traced her ancestry back to Isom and Leddie McCain, whom McCain’s great-great-grandfather owned at Waverly, the McCain family plantation in Carroll County.

The black McCains, as they call themselves, join descendants of the white McCains at family reunions every two years in the Teoc community where the plantation once stood. The senator never attended any of the reunions due to scheduling conflicts, he said, but his brother, Joe McCain, attended the reunions in 2006 and 2008. One reunion photo shows a magazine open to an article on the senator’s time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, where the naval aviator was held captive for nearly six years.

In a video from the most recent Teoc reunion in 2017, Lillie McCain said the meetings of the white McCains and the black McCains helped them “come to understand that we are all connected as one race.”

"Dr. King said, ‘I have a dream that one day the sons and daughters of slave owners and the sons and daughters of slaves will come together at the table of brotherhood,’ and he followed that with a passionate, ‘I have a dream,’” Lillie McCain said. "That dream is being realized by us.”

Mississippi Flag: A Symbol of Hate or Reconciliation?

The Mississippi Sons of Confederate Veterans are fighting hard to keep the state flag to honor the Confederacy. Others are fighting back.

The Black McCains took part in the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s, leading voter registration drives and taking on Jim Crow laws. During the Civil Rights Movement, Lillie McCain marched for the desegregation of public schools in Mississippi, getting arrested in the process. For her senior year of high school in 1968, she chose to attend a previously all white school.

“I was being burdened by the idea that I’d put so much energy into the desegregation movement and then I didn’t go,” she told The Reach in June of this year. “It’s not something I’ll forget.”

In his concession speech after Barack Obama—whom Lillie McCain supported—defeated him in the 2008 election, McCain said he recognized the “historic” nature of the moment and “the special significance it has for African-Americans and for the special pride that must be theirs tonight.”

Before his death, McCain requested that his former rivals Bush and Obama deliver eulogies at his funeral.

Lillie McCain is now retired and living in South Carolina—the same state where a racist smear campaign and a political misstep over the Confederate flag ended John McCain’s first presidential campaign more than 18 years ago.

Ashton Pittman covers politics and elections for the Jackson Free Press. Follow him on Twitter @ashtonpittman. Email him story tips to [email protected]. Read more about the Confederacy and the Civil War at jfp.ms/slavery.

More stories by this author

- Governor Attempts to Ban Mississippi Abortions, Citing Need to Preserve PPE

- Rep. Palazzo: Rural Hospitals ‘On Brink’ of ‘Collapse,’ Need Relief Amid Pandemic

- Two Mississippi Congressmen Skip Vote on COVID-19 Emergency Response Bill

- 'Do Not Go to Church': Three Forrest County Coronavirus Cases Bring Warnings

- 'An Abortion Desert': Mississippi Women May Feel Effect of Louisiana Case

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus