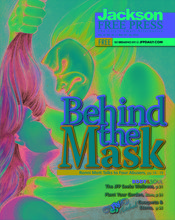

In honor of former Gov. Haley Barbour's pardon of several killers of domestic partners, we are featuring one of award-winning journalist Ronni Mott's domestic-abuse stories at the top of the site each morning. See the full archive here. This 2010 story is about reversing the battering cycle. The JFP Chick Ball raised money to seed the area's first batterers intervention program.

Most of the names of people and institutions have been changed to protect the identities of the individuals who shared their stories.

About 10 minutes before Jasmine stabbed her boyfriend, William, he had her on the floor of her grandmother's house, choking her to the point that she passed out. It wasn't the first time he had attacked her in that way, but it would be the last, she said.

The couple fought constantly, and after about eight months together, they moved into Jasmine's grandmother's vacant house in Rankin County after being evicted from an apartment because of their fighting. Both of them ended up in jail after one particularly ugly incident, and the court directed them to take anger-management classes. Jasmine lost her job due to one too many absences, and she asked her ex-husband to take care of their three children, at least temporarily.

About a month after moving into her grandmother's vacant house in Rankin County, Jasmine and William started fighting one Sunday after coming home from church.

"I was just so angry the whole day. Everything he was doing was just really making me upset," she said, adding: "The Lord was really trying to tell me something. … I was miserable."

The next morning, Jasmine had made up her mind. She would pack up William's stuff while he was at work. She'd had enough.

"I was done," she said, but William wasn't. He attacked her before leaving for his job, pushing her to the floor and choking her until she blacked out.

When she came to, it took her a minute to realize where she was, Jasmine said.

She ran to the kitchen where she grabbed a "little steak knife," and she shouted for William to leave, just go. "If you touch me again," she screamed, "you'll be sorry."

"He jumped back like he was going to hit me," she said, "and I already had the knife in my hand. … It happened so quickly. … It was like I was out of my body."

Jasmine had stabbed William in the ribs up behind his left arm.

"Baby, I'm sorry," she kept repeating, as she called 9-1-1 to get help. "I was so afraid. Lord knows, I'm not trying to kill this man. … All I could think about was my children."

She thinks that the police knew it was self-defense. She had told the dispatcher what took place. William, though, lied to the police about what happened, saying he had accidentally stabbed himself while they were wrestling on the bed, she said.

The police didn't buy his story. William was the injured party, and the police arrested Jasmine, charging her with domestic assault, while they took William to the hospital.

While some women learn to cope with abuse by becoming submissive, or they try to manage the situation, Jasmine's reaction was to fight back. And when women fight, they tend to do so with weapons more often than men, who tend to use only their strength.

"Victims of violence often retaliate and resist domination and battering by using force themselves," states a 2002 paper from Praxis International, "Re-examining Battering: Are All Acts of Violence Against Intimate Partners the Same?" Non-profit Praxis International is a research and training organization that works toward ending violence for women and children, based in Duluth, Minn. In the paper, the authors dub battering by victims "resistive/reactive" violence.

The overwhelming majority of domestic abusers are men, but women batterers are no longer rare. Nine of the 118 Mississippians in the state's only Batterer's Intervention Program are women, and, unlike Jasmine, some of them are primary abusers, not just reacting to being victimized.

"We try to work through the court system to make sure that women who are defending themselves aren't charged the same as other perpetrators," said Sandy Middleton, director of the Center for Violence Prevention in Pearl, who brought the intervention program to the Jackson area. The program operates in Hinds, Madison and Rankin counties. "In a home where you have a domestic-abuse situation," she added, arresting a woman for defending herself is "just re-victimizing the victim."

On the other hand, "a lot of women become the aggressor seeking survival," she said, citing the 2002 film "Enough" with Jennifer Lopez as an extreme example of an abuse victim seeking revenge.

"The more women are in places of leadership and the more we're out in the work force, the more we're going to see some power and control issues in women," she added.

Still, more than 85 percent of domestic-abuse victims are women, and most of the abusers are men, making up 83 percent of spouse murderers. Accurate statistics about non-lethal domestic violence are difficult to come by, as domestic violence is one of the most chronically under-reported crimes, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. And the National Institute of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that only about one-quarter of all physical assaults, one-fifth of all rapes, and one-half of all stalkings perpetuated against women by their intimate partners are reported to the police. Minorities and the poor are over-represented in domestic-violence statistics, probably because calling the police is a last resort for women with other resources.

Due to concerted effort from many organizations, women are more knowledgeable about getting protective orders and getting more of them faster, according to judges and court clerks, said Heather Wagner, director of the Domestic Violence Division in the state attorney general's office. And people are more aware of what domestic violence is, especially that it doesn't always consist of physical violence.

The Batterer's Intervention Program is designed to get to abusers' core issues, which revolve around power and control.

Like rape, which is less about sex than it is about exerting control over another person, domestic violence is not about anger, and anger management programs have little effect on the problem.

Each week, the intervention program touches on a different aspect of abusive behavior: intimidation; emotional abuse; isolation; minimizing, denying and blaming; coercion and threats; economic abuse; using children against a spouse; and using male privilege. Each of those facets can include physical or sexual violence. Participants share and interact about their experiences under the guidance of trained facilitators, and they watch situational films that demonstrate what each of the behaviors looks like.

"They may not even realize it, but the male facilitator and the female facilitator are modeling appropriate, respectful relationships with each other in front of them every week for 24 weeks," Middleton said.

"A lot of guys have never seen a man really treat a woman with love and respect. They don't see that. … They don't recognize a healthy, caring male/female relationship. They don't know what that is," she said, "and they get to see that."

‘I Did Damage Some Things'

Soft-spoken Casey, 27, and his wife of five years, Amanda, argued a lot, he said, as he nervously popped a mini-Altoid every few minutes.

Ultimately, it was a judge's decision that got him into the program, but it was a loud and destructive argument that put him in front of the judge.

"I did damage some things," he said. He broke a chair, and he threw food at his wife, using intimidation and threats.

Casey is nearing the end of the 24-week Batterer's Intervention Program, with about six weeks to go. At first, he considered the program a waste of his time. It's a common reaction: Most of the court-ordered participants initially believe they don't belong there. The offense that got them into court wasn't that serious, they say, and it's all "just bullsh*t," as Casey put it.

It's an attitude that comes from every participant in the beginning, Middleton said.

"It's completely across the board. If you'll look at it, this type of individual doesn't accept responsibility for most things in his or her life. It's a pattern of behavior for them to blame their actions on other people. They've made a lifetime of excuses for themselves and their own behavior by blaming it on somebody else. So naturally, they would come into the program thinking there wasn't anything wrong with them," she said.

That way of thinking often disappears when the participant becomes involved in the process, however.

"[T]he more I started coming, the more I started noticing signs of my aggression and anger," Casey said. "I didn't think past the end of my nose (before the program). I didn't really think about the consequences of us arguing. All I thought about was what was happening right then and there, and how I was feeling."

He remembered a class where the facilitators asked the participants whether they treated people fair. After giving it some thought, he realized that he didn't. Fair would be treating them how he wanted to be treated himself. Instead, he said: "I treat people how I think they should be treated. To treat people fair is hard."

At first, Jasmine couldn't understand why she had to go to the program either.

"I was angry when I started coming. I was so angry," she said. Her thinking was that "If he had never put his hands on me, this wouldn't have happened."

Jasmine, 37, is living with her mother and working full time to find a new job. Her children live with their dad while she works to get her life back on track, but she sees them every day.

"Now that I'm taking this class, I realize why I tolerated some of the things in these relationships I had," she said.

Slowly, she's realizing how the events of her life have put her in the position she's in.

Jasmine was pleased and surprised to find out her class was all ladies, she said. An anger-management class she took after a previous arrest for domestic violence was mixed, men and women.

"I would always be so uptight in that program," Jasmine said. "Here, I feel free, free to express myself, because there are no men around. Men and women have a different point of view when it comes to domestic violence."

Male Privilege

Paul, 40, is nearing the end of the program, with about three weeks left. He and his wife, Gloria, had separated for nearly a year and were back together, trying to work things out without a lot of success. They were on the verge of calling it quits, sleeping in different rooms, not communicating.

"We basically were living a separate life while living together," he said.

One night Gloria came into Paul's room, waking him up.

"I'm thinking that she wants to be intimate," he said, and they began to kiss.

Suddenly, she withdrew, starting what he called "a crazy outburst."

"I can't trust you," Gloria said, struggling and kicking against him.

"At first, I didn't know what was going on," Paul said. "So I grabbed her."

Paul's described the event in an unemotional, flat tone of voice. He claims he didn't hurt her, but whatever happened that night, it was frightening enough for Gloria to call the police, who strongly suggested to Paul that he leave the apartment, which he did. The next day Gloria filed a domestic-assault charge against him and took out a restraining order.

"I'm not saying I didn't do things along the way," he says. "Since I've been in the program, I've learned some (abusive) behaviors that I had."

Learning to take responsibility for their actions is integral to the success of the Batterer's Intervention Program, Middleton said. For abusers in mid-life or later, it's especially difficult to change.

"They have to believe in it," she said. "They have to see it and believe that ‘this is going to work for me; this is going to be a positive change in my life."

Like all the participants in the program, Paul also discovered that domestic abuse wasn't just about physical beatings, something he said he had never done. "I never physically grabbed her or beat her up," he said.

"There's verbal (abuse), there's mental (abuse)," he said, adding, "I had some control issues."

Paul tried to control his wife's money, for example, giving her just enough to pay the bills and wanting to know where she spent every penny.

His behavior is a classic symptom of abusive behavior, especially for sole breadwinners in a family. Economic abuse often goes beyond controlling how a partner spends money, but can also extend to preventing the partner from getting work, forcing her to beg for money and not letting her know about or have access to funds.

Paul was in the U.S. Navy for years, where "most people had an aggressive tone," he said. He and his wife probably spent more time apart than together during their 20 years of marriage. He would be at sea for months at a time, returning for a few weeks or a month before deploying once again, something that doubtless kept the marriage intact.

While he was deployed, his wife ran the household and raised their three children. Trouble began when he got out of the military and tried to take the reins as head of the household. Where before time at home would almost be like a honeymoon, suddenly he was a full-time husband and father and exerting his domination over the household.

"The little things that I didn't notice (about her) and that she didn't notice about me really started to clash," he said. He added that he doesn't really get mad often, but is "explosive" when he does.

He began to find fault with the way Gloria was doing things, including how she disciplined their children and how she spent "his" money.

"Before, she handled all the money. … Now, when I got out (of the Navy), I'd say, ‘we're going to do this, and we're going to do that," Paul said.

Paul seemed almost surprised that his wife put up resistance, eventually leaving him for nearly a year. Gloria had learned an independent, self-reliant existence, and couldn't tolerate his "king of the castle" behavior.

At first, Paul didn't feel that his actions justified the punishment and expense of the program. (Participants must pay for the classes to partially cover the cost of facilitating and administering the program: $25 for each class or $600 for all 24 weeks. Their fees, however, don't cover the whole tab. The rest of the cost is paid through a combination of federal, state and non-governmental grants, and private donations.)

Just a few weeks into the program, however, Paul began to have a change of heart.

"It turned for me when I could see myself in a situation. That was a turning point. I think it was about two or three weeks into it. I really realized that there were some areas I need to work on," he said.

The way the program is designed, participants who share their experiences help others who might have had the same type of encounter, and facilitators encourage everyone to share.

"I might have an issue going on that (another participant) might have already experienced or gone through. He could give me some insight," Paul said. "Those experiences come from people of all ages and races."

Using Intimidation

Marty, 29, considers his situation unique. He was trying to end a relationship, he said, and his girlfriend wanted his cell phone, which she had given him as a gift. Like most people, he had private numbers and other information on the phone he didn't want anyone else—especially her—to access.

"She tried to take the cell phone, and I kind of pushed her," he said. "It was substantial enough to make her stumble, but I would say it wasn't a push to hurt her."

At the time, Marty and his girlfriend were both employed as corrections officers. He worked as a K-9 officer, using dogs to search for contraband in prisons and halfway houses. He was also a linebacker in college, and at 5 foot 10 inches and 256 pounds, it's easy to image how intimidating his heavily muscled physique alone could be.

His girlfriend called the police who arrested Marty, and the court ordered him into the Batterer's Intervention Program.

Today, Marty has completed the 24-week intervention program, but like the others, he didn't think he deserved to be there at first.

"I just felt like I was being picked on," he said. "But as class went on, I enjoyed going. It was a pleasure.

"What turned the corner for me was being involved with people who knew what I was going through."

He was able to see himself in the others, he said, and felt they were there to help him, not look down on him. It surprised him how calm his instructors were, and how calm he became. Some of the instructors had gone through exactly the things he had, and had learned how to deal with life in other ways.

"The different ways to handle the situation got my attention," he said. "Walking away, or talking it out, or the way you look at someone can actually be intimidating. I didn't know that."

One of the methods used in the program is showing the participants short videos demonstrating different aspects of abusive behavior—"vignettes" Marty called them.

"It was like looking in a mirror, sometimes. Like, standing over your partner and talking at her, instead of to her. I caught myself doing that a lot," he said. "… Before the program, I couldn't see it."

Middleton said that the participants complain about seeing too many videos; however, there's no denying their effectiveness.

"The videos are what, ultimately, they make a connection with," she said. "They realize it's them on that video. … It's like a dose of cold water for them realize, ‘that's me.'"

Casey called the videos "cheesy," but, like Marty, he recognized many of his abusive behaviors in them, like, "yelling, slamming stuff, minimizing" his wife's concerns and not taking her seriously.

Participants who don't recognize themselves in the videos are probably looking straight into their own worst sides, Casey said. "Most men are not aware of the behaviors that they're doing," he ventured. "… Ultimately, it's up to the person. If you want to change, you'll pay attention, soak some stuff in."

Through the program, Marty was also able to see his pattern of consistently blaming someone else for his behavior, or making his partner feel stupid when she disagreed with him even over little things. Marty also used the Bible to get his way, another aspect of male privilege.

"The man's supposed to be the head of the house," he said, once assuming that what that meant was that his way was the only way. "The Bible says that, but it doesn't mean it like that. The man is the head of the house, but it doesn't mean he controls everything."

He now sees that decision-making should be a shared activity, not that what the man says, goes. Before the program, Marty wouldn't allow his partner's input into the simplest things, like the choice of a restaurant or a movie.

"It was my choice," he said. "It was never, ‘what do you want to see.' It was ‘we're seeing this.' It was basically a controlling-like situation. I didn't see anything wrong with it because I was caught up in ‘the man's supposed to run everything.'"

To this day, though, Marty isn't clear how he came to that belief. Growing up, his mother ran everything. "I don't know where I got that from," he said. "I can see myself as a better person (now). I don't actually get mad any more," he said.

Marty also benefitted from hearing other's stories, enabling him to understand that he wasn't the only person who reacted to life the way he did. It was an eye-opening experience.

"One day, this guy, I'm telling you, everything he said was exactly the stuff I did. It felt like I was sitting in a place and this guy was me, and I said, ‘Wow. He's saying exactly what I need to be saying.'"

Listening to someone else say the things in his own mind, Marty said he could see how wrong-headed the speaker was. "I wanted to say something," he said, recalling the incident, "but I can't because I do the same stuff."

Breaking the Cycle

The first day Jasmine met William they became a couple.

"At first, I was attracted to his looks," she said, and they both "fell in love at first sight." Soon, though, she discovered that he was full of lies.

"He told me he was a college graduate; he told me he had real-estate property, even though I don't care about all that," she said. "I want a man that's going to work; that's independent; and that's respectful. I want a God-fearing man, first of all. And I thought that this was the type of person that he was.

"I promise you, I felt it in my spirit the first week that he was a freeloader, he was an alcoholic. I felt it, and I just could not let it go. Like I could save him."

But William didn't want saving, and when Jasmine confronted him about his behavior, he would choke her, put his knee in her stomach, squeeze her breasts and pull her hair. Her once long hair is short now, she said, because she became so stressed out her hair fell out in clumps.

William told her she was too aggressive and headstrong, and Jasmine started doubting herself, thinking: "Maybe I need to bow down a little bit. Maybe I am too aggressive.

"I never had a man to help raise me, so I don't know how to be submissive. All I do know is how to love somebody, and that's what I want in return."

Despite the abuse, Jasmine, a divorced mother of three (two teens and a 10-year-old), stayed in the relationship for eight months. William didn't have a job, and then Jasmine's ex lost his job and wasn't able to make his child-support payments. Jasmine fell behind on bills and lost her apartment.

"I really had no help," she said.

She couldn't let William go, she said. When he cried and begged to come back, she relented, even after losing her home, her job and her children.

Jasmine's story is typical of the cycle of domestic abuse, beginning with a push into quick involvement. William began lying to her from the beginning of the relationship. He belittled her and was physically violent, but manipulated her into accepting him back on more than one occasion, apologizing, crying and begging until she let him come back.

Middleton indicated that violent, abusive relationships can become co-dependent, just like other kinds of dysfunctional and self-destructive behaviors among partners.

Domestic abuse can also manifest generationally: Abused children often become abusive parents and partners.

"I didn't have a father around," Jasmine said. "I went through some things in my childhood. I was molested when I was a child by my mom's boyfriend."

It was a secret that she had kept to herself, not even telling her mother until about five years ago, but one she feels has influenced the kind of men she's had in her life. Since her divorce in 2005, she's had a string of abusive relationships, culminating with William, and her ex-husband cheated on her.

Of the four abusers interviewed for this story, three of them, including Jasmine, had abusive childhoods.

Paul's parents divorced when he was young. "My father, he was abusive," he said. "I can remember as a child, 3 years old, there were incidents with (my mother)," he said, and his mother used corporal punishment on him.

"Sometimes it was a slap or a physical punch," he said.

Casey grew up with an older sister and a single mom, who had a decidedly corporal style of punishment. "I got whooped with whatever was around," he said. "I just thought that every kid got whooped." His mother used "whatever was in reach," he said: house shoes or a switch.

Multiple violent relations are also common among abusers. Jasmine had another relationship go sour when she discovered the man was freebasing, lacing his cigarettes with cocaine. "I confronted him about it and told him we were going to have to stop seeing each other for a while, and that he needed to get some help," she said. She made calls on his behalf, looking for a treatment program, trying to help.

"He never could make the time to go," she said. Instead he showed up high at Jasmine's apartment one night and ended up kicking her in the face with his steel-toed workman's boots as she sat in her car.

"Right here," she said, gingerly touching the spot just under her right eye with her fingertips. She got away and called the police, who arrested the man for aggravated assault, but Jasmine isn't clear what happened to him after that, and doesn't seem particularly interested in finding out.

Abusers often blame drugs or alcohol for their violent episodes, and about 50 percent of abusive relationships also have a history of alcohol and/or drug abuse, reports the Alabama Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

"Men often blame their intoxication for the abuse, or use it as an excuse to use violence. … t is an excuse, not a cause," states the organization's website. "Taking away the alcohol does not stop the abuse."

Several months after her arrest for stabbing William and about halfway through the 24-week intervention program, Jasmine said she sees these recent events as positive.

"Honestly, that was the best thing that could've ever happened to me—for that to happen and for me to go to jail, because it just woke me up," she said. "I couldn't do anything but cry and pray, cry and pray.

"I prayed for him," she said, a bit of disbelief in her voice.

"I don't want anything to happen to him," she prayed. "I don't want anything to happen to me. I just want to get back out here to my children. You don't have to worry about me going back with this man. I'm done."

Jasmine pleaded guilty to simple assault on a plea bargain where she agreed to attend the Batterer's Intervention Program in Pearl. When the judge ordered, "no contact," she was more than happy to cooperate.

"I can break the cycle," she said. "I don't want my children to be abused and I don't want them to be abusive. What I need to do is come to reality, look at happened to me in my past, deal with it and know that it happened. I can't change it. Accept it and move past it, and not blame anybody else."

A New Day

All the participants find that the Batterer's Intervention Program is touching on other areas of their lives, not just their relationships with spouses.

Marty feels that the program will have a lasting affect on his life. As he relates the circumstances of his current relationship, there's a hint of amazement in his voice. Since completing the class, Marty re-established a relationship from his past that he characterized as "different as night and day" from the way things used to be.

"We talk; we have fun now. I involve her in a lot of stuff now," he said, asking her what she wants and soliciting her opinion instead of controlling every situation. "I'm not saying I'm perfect, but it has made me a better partner, because I try my best to do whatever she asks me," he said.

It took a bit of getting used to for his partner, though, who knew him before the program. At first, she was afraid to ask for what she needed.

"Now we just sit down and talk," Marty said. "I want to please her."

It's a method he learned in the program, where all participants are encouraged to speak up and tell the others what's going on.

"As you open up, they open up," Marty said. He added that he's also learned a new definition of intimacy.

"I never knew a hug could be intimate, or a kiss, or just having an intimate conversation," he said.

Casey and Amanda are trying to work it out together.

"It has its ups and downs," he said of their relationship. Since the start of the program, Casey is experiencing a renewed affection for his wife, something that he finds surprising.

"I'm starting to have the same feelings about her now as when we first got together. We're really enjoying each other's time, even though we've had some disagreements since the program started," he said. "… I've definitely noticed a change in our relationship."

He sees now that what people told him prior to his arrest—walk away, it's not worth it—is exactly right.

"I wasn't in a position where I could listen," Casey said. "Even if I heard what they were saying, I couldn't comprehend it. … When people are in that situation, they're selfish."

Casey added that communication is key. "If you're both talking, there's no reason to get upset and start punching and kicking, if you're really talking about it," he said.

Paul, who is attending classes at Holmes Community College and working full time, sees that the program has especially influenced his relationship with his children, two of whom are still in elementary school. They are surprised by his newfound ability to respond to their needs instead of only thinking about his own. Their dad now hears them, and they want to be with him.

"They see me differently now. … I wasn't engaging them before. I would work, come home and when they saw me again, I was going out the door. It was always, ‘sit down; be quiet; don't bother me right now.' But now, I'm interacting with them.

"With the oldest one, it's like day and night," he said of his daughter, who is college-aged. "Before, we were like two ships passing in the dark. That's how we were. If I didn't see her, she didn't see me. Now, she'll call and text me."

His daughter, he recently learned, is pregnant, so Paul is going to be a grandfather for the first time. He's been helping her out, taking her to doctor's appointments, where before he probably wouldn't have been so generous.

"I probably would have been fussing, yeah, I probably would be," he said. "… The night she told me, I didn't get bent out of shape. I sat down and I listened to her. And then we started thinking about things we needed to be doing from that point. I didn't explode on her. I didn't tell her, ‘Oh you're stupid; you made a mistake; what are you doing.' … I think (the program) helped me out there.

"Me and her, we've had some bad times," he admits.

At this point, he isn't holding out a lot of hope for the marriage.

"I love her. I miss my family. But, no," he doesn't think he and Gloria will get back together, he said.

Paul and Casey believe that their spouses would benefit from going through the program. It's not enough, they said, when only one partner goes through such an experience, and some relationships aren't able to weather the changes. But the Batterer's Intervention Program isn't designed to be marriage therapy.

"They couldn't make the strides that they do with their wives and girlfriends in the room. … They wouldn't bare that much of themselves," Middleton said.

"We're not about restoring relationships," she continued. "We just want to stop the violence."

‘It's Been Good'

Paul seems a little uneasy addressing how he would keep his new skills intact after the end of the program. He said he's going to keep himself focused and centered on his college courses, working toward a nursing degree.

"I think I will be OK. I've only been going (to the Batterer's Intervention Program classes) once a week, but this has been constantly on my mind," he said. "I'm still living it. We're still separated … but neither one of us is talking about divorce. … To be honest with you, I'm torn. I'm afraid if I go back, she's got this ace in the hole. … I don't want to live like that. I don't want to feel like I'm under the gun."

Nevertheless, Paul said confidently that he would share what he learned in the program with others, not by telling that they're wrong, but by encouraging them to look at their behavior.

"For me, it's been good. … I've learned a lot," he said.

Marty can now see controlling behavior among his family and friends. He has an uncle, he said, who is extremely controlling and friends who display the same type of behavior he once did.

Since taking the class, he has been disassociating himself from those people, or trying to have them see how their attitudes and actions are poisoning their relationships. Some of his friends are actually seeking Marty out for his advice, a situation he finds mutually supportive.

"I have someone to talk to, too," he said.

Some of the blame for the prevalence of domestic violence has to go to the mainstream media, Marty said, who "advertise" violence to make money. "It's entertainment," he said, and women, especially, aren't given the information they need to change their circumstances. Relating an incidence where a woman friend refused to report her abuser, he said: "I think she's afraid, but she's (also) brainwashed" into passivity.

Once a happy, vital young woman, today, she's isolated, her abuser controlling every part of her life. "Her friends don't come around anymore because they feel she's stupid," he said. "She doesn't go anywhere now. She just stays at home.

"I wish they'd open the program to people who aren't forced to go in, have it open to everybody. … Sometimes I just feel that men need someone to talk to on their level. That's where the class helped me," Marty said. "… There wasn't anyone in the class that didn't do nothing to get there."

Middleton said the program is open to "volunteers," men and women who recognized their need for help before they get into real trouble, and she is also looking for ways to extend it to include support after participants complete the program. To date, the Batterer's Intervention Program boasts a zero recidivism rate.

"They can always come back; we tell them that … just to keep it fresh in their minds," she said.

Jasmine is looking forward to working again, getting her children back and then going back to school. She's a caregiver by nature, she said, and wants to get a nursing degree. She's also looking forward to having a grown-up relationship with a grown-up man who treats her with respect and takes responsibility for his life.

"I'm still trying to figure it out," Jasmine says. "Know what I'm saying? I'm still trying to figure out why my actions are the way that they are. But I do know now that when a man hits me, that's not love. I know that he's going to do it again."

After about 10 weeks in the program she already knows to disengage from arguments, and has seen how effective it can be.

"It's making me a better person," she said, and she isn't afraid to be on her own any more. "You can't save a person that doesn't want to be saved," she said, "I'm not going to let anyone control my life again."

The Batterer's Intervention Program

The Batterer's Intervention Program is designed to curb domestic violence through coordinated community response. Based on the Duluth Model developed in 1980 in Duluth, Minn., the Center for Domestic Violence Prevention held the first class for batterers Sept. 15, 2009. Currently, it is the only such program in the state of Mississippi, and proceeds from the Jackson Free Press 2009 Chick Ball provided the seed money for initiating the program.

Judges direct batterer's—usually first-time offenders—to attend the 24-week program, which is staffed by trained facilitators and uses a range of tools to teach offenders alternatives to coercive, controlling and abusive behavior in intimate relationships. Individuals who recognize a need for intervention can also sign up for the classes without a court order.

The program works to ensure safety for the partners of the participants while also working to end domestic abuse by creating a culture of deterrence.

To find out more about the program, call 601-932-4198, or visit The Center for Domestic Violence Prevention website, http://www.mscvp.org.

To find out about the Jackson Free Press 2010 Chick Ball, scheduled for July 24, call ShaWanda Jacome at 601-362-6121 x16.

If you are a victim of domestic violence and need help, call the 24-hour crisis hotline: 1-800-266-4198.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 157902

- Comment

Bravo, Ronni. Bravo.

- Author

- Sophie

- Date

- 2010-05-19T21:41:00-06:00

- ID

- 157903

- Comment

I second that, Ronni. Congratulations and thank you.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2010-05-19T22:40:25-06:00

- ID

- 157912

- Comment

Enjoyed the read and learned a few things about myself and a few others - family and friends, male and female. Domestic Violence is a real and sad issue in the sense of being capable of turning victims into perpetrators and pretty much destroys an environment down to a single fiber.

- Author

- Don Smith

- Date

- 2010-05-21T08:15:29-06:00

- ID

- 157914

- Comment

Too bad the Irbys were not a part of this program: If we are to believe her reports of physical abuse-not only against her but also her daughter. I have worked with both the abused and the abuser and I must admit that usually, they are both victims coming from histories of our classic abuses: physical, emotional and sexual. (Often starting in childhood and in the home-house) Occassionally, the abuser is the female and the male is too embarrassed to talk about it or to file charges. It is so sad when hands become weapons to harm rather than a special body part that can give comfort and joy. Thanks Ronni. This is a subject that we need to continue dialogue on.

- Author

- justjess

- Date

- 2010-05-21T12:34:51-06:00

- ID

- 157916

- Comment

As a facilitator for this program - thank you! I am so grateful for the Jackson Free Press's efforts to ensure that domestic violence remains front page news. Fantastic job, Ronni!

- Author

- Whitney

- Date

- 2010-05-21T13:42:56-06:00

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus