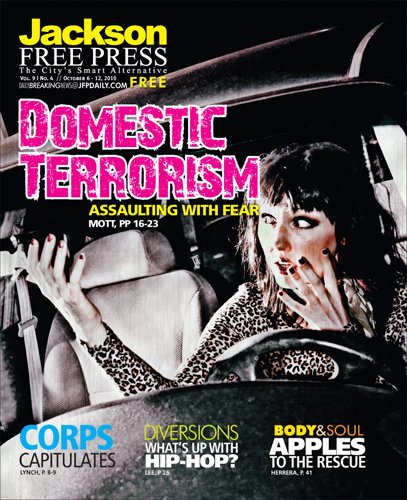

In honor of former Gov. Haley Barbour's pardon of several killers of domestic partners, we are featuring one of award-winning journalist Ronni Mott's domestic-abuse stories at the top of the site each morning. See the full archive here. This story was motivated by Barbour's original grant of clemency to a wife-killer in 2008.

Adrienne Klasky knew for years that Michael Graham would kill her. She just didn't know when it would happen.

Klasky, daughter of a prominent family in the Mississippi Gulf Coast city of Pascagoula, was by all accounts, a lovely and loving person. Most of all, she loved life, her friends say.

Nancy Northern, her niece, remembers her aunt fondly. "She was a lot of fun," she said.

Klasky wanted to be a mother. Like many women, though, she struggled with her weight, and romance and self-esteem always seemed just out of reach. She knew Graham from Pascagoula High School, but for Klasky and her friends, Graham and the crowd he ran with were from "the wrong side of the tracks."

Her friends and family were taken aback when Klasky married Graham in October 1980. They thought she could have done so much better. Eleven months after they married, Klasky gave birth to baby Michael in September 1981. Kevin was born less than three years later, in January 1984.

Graham, however, never quite fit into Klasky's social world. People who visited their home describe him as morose. He didn't speak to visitors; instead, he parked himself in front of the TV in his rocking chair, isolating himself and ignoring everyone else.

From the day Northern met Graham, he scared her. "I just didn't care for him," she said. "Something about his eyes."

Graham apparently had trouble holding down a job. For a while, he worked in Klasky's family business, Brumfield's Department Store, selling men's clothes. Her dad, Lyle Klasky, reached out to his contacts in the community to find other employment for the father of his grandsons, but no one remembers Graham having a job for more than a few months at a time.

"I remember him and Adrienne fighting about that," Northern said.

It wasn't long after Klasky became a mom that she began telling friends that Graham was abusing her, most of it psychological, but he also pushed her around. On at least one occasion, Klasky had marks on her neck, evidence that her husband had tried to strangle her. She didn't report the abuse to the police, though. In Pascagoula, Klasky and her family were well known, and the young mother was embarrassed about her failed marriage, not wanting to bring attention to it and cause her family pain.

Klasky stuck it out for nearly six years before calling it quits. She and Graham separated March 19, 1986. She went to her family and friends for support, back to her tight-knit community.

That's when Graham began stalking.

They Couldn't Do Anything

"A lot of (victims) are afraid to leave," said Lt. Tammy Gaines of the Hinds County Sheriff's office victim's assistance program, adding that most stalkers know their victims. Leaving a violent relationship often precipitates additional violence or escalates the partner's violent tendencies, making it an extremely dangerous time for a victim.

In 1986, Mississippi, like every other state in America, had no laws against stalking. When Klasky reported Graham's threats to the police, they told her they couldn't do anything unless he physically hurt her. Just following and scaring her half to death wasn't illegal, they told her. Pascagoula's police chief at the time, Larry Lee, apologized to Klasky, but said that technically Graham hadn't broken any laws.

California was the first state to adopt anti-stalking laws in 1990 after a stalker murdered "My Sister Sam" TV actress Rebecca Schaeffer in July of the previous year. Schaeffer was 21 when Robert John Bardo shot her in the chest when Schaeffer answered her door. Bardo had been stalking Schaeffer for three years, off and on, and had a history of stalking other celebrities.

In Mississippi, celebrity stalking is usually limited to people who work in the media, because they are the local celebrities, said Lt. Jeffery Scott of the Hinds County Sheriff's office. It's much more likely that the perpetrator and victim know each other.

"It's more of a love type of thing," he said.

In 1992, the U.S. Congress tasked then-Attorney General William Barr to conduct research on the problem and to develop a model for anti-stalking laws for the states. The result of that research provided model code the following year, and the federal government encouraged all state governments to adopt felony stalking laws.

By September 1993, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had put stalking laws on their books.

Mississippi's first stalking law, adopted in 1992, provided for a misdemeanor with a maximum of one year in jail and/or a fine of $1,000 for a first-time offender. Under the original law, a stalker's victim had to prove that he or she was in imminent fear of losing her life to have police and the courts move to protect her, a nearly impossible standard to prove.

"[O]ur stalking law is tied to putting the victim in fear," said Assistant Attorney General Heather Wagner, director of the domestic-violence division in the Mississippi attorney general's office last year. "It goes a little further than that. You have to prove that the person who's doing the stalking is doing it to put the victim in fear of death or serious bodily injury. It's not enough just to terrorize the person so that they're scared to walk out the door; they have to be scared of death. And that makes it a very difficult hurdle to prosecute."

In July of this year, the state adopted an amended stalking law, making it much easier to prosecute a stalker. The law now states that stalking includes "conduct (that) would cause a reasonable person to fear for his or her own safety, to fear for the safety of another person, or to fear damage or destruction of his or her property."

The new law also added a tougher felony aggravated-stalking subsection, aimed specifically at perpetrators who threaten to kill their victims or a third person, or use deadly weapons to punctuate their threats. Aggravated stalking carries a five-year, $3,000 maximum punishment, and adds another year and another $1,000 if the victim is under the age of 18.

The penalties aren't harsh enough for some. Northern chuckled low when asked what she thought they should be. "I don't know if I can say that," she said. "... They need to be locked up. It's scary. How do you know that somebody's not just going to snap one day and kill somebody?"

"When you couple domestic violence with the propensity to stalk, you have somebody who's potentially lethal," said Sandy Middleton, executive director of the Center for Violence Prevention in Pearl. "... It all comes from that root belief that they have a right to do this, and it's appropriate behavior," she added, saying that stalkers and abusers display the same type of obsessive, controlling and dominating conduct.

Middleton believes the new law is solid, but that it will require some new thinking and new questions for law enforcement. "I think everyone's taking it seriously," she said.

Graham, like many stalkers, didn't limit himself to just stalking Klasky. He also stalked her family and friends. Phone records, lost during Hurricane Katrina, showed a repeated pattern of calls from different pay phones in the Pascagoula and Moss Point areas, first to Klasky, then to her business number, her friends and to her family, perhaps a half-dozen calls one right after the other. He never spoke or identified himself, but everyone believed it was Graham; sometimes they saw him as he called from public phone booths.

Still, at the time, none of that was illegal.

On March 30, 1987, a year after they separated, and eight months after their divorce came through, Klasky finally secured a protection order against Graham after a friend witnessed him hitting her with enough force that her glasses flew off her head. Now, police had a reason to give her a bit of security, even though they didn't arrest Graham.

The stalking didn't stop. It became so pervasive that it turned into a joke, something that just happened all the time. "There goes Adrienne," someone would say, "and there's Michael, following her," another would chime in. Over silent phone lines, folks would tell him to show his face or come on by.

‘Assault by Creating Fear'

Stalking covers a wide spectrum of threatening behavior to intimidate victims. Among those behaviors are: making unwanted phone calls (including hang-ups); sending unsolicited or unwanted letters, e-mails or text messages; following (including tracking by GPS) or spying; showing up at places without a legitimate reason; waiting for victims in places they frequent; giving or leaving unwanted gifts or flowers; and posting private, intimate or false information on the Internet, in public places or by word of mouth.

Technology makes stalking that much worse. Stalkers can access their victim's computer for personal or sensitive information, install stealth software where they can see every keystroke their victim makes and steal money or credit electronically. They can also post photos or intimate details on social networking sites where the information can be instantly seen by hundreds, perhaps thousands of people.

"Stalking and domestic violence are not limited to any one group. It crosses race, gender, economic status," Scott said, relating an incident of an attorney being stalked by a woman with whom he had ended a relationship. Eventually, the woman threatened to kill him, his new girlfriend and then herself.

"This guy was scared, scared for his life," Scott recalled.

While most stalking perpetrators are male, it's not uncommon behavior for women. With more than 3.4 million reported incidents of stalking in 2006, more than 2.5 million involved female victims ,according to a 2009 Department of Justice study. The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence says that 87 percent of stalkers are male. And men usually stalk women: 94 percent of female victims have male perpetrators, while 60 percent of male victims have female stalkers.

In Jackson, guys on the streets call their female stalkers "kill me's," Scott said.

"She'll be outside knocking on the window," he said, rapping on the

arm of his chair for effect. Pitching his voice higher, like a woman's, he mocked: "You're gonna to have to kill me before I'm gonna leave."

More than half of all stalking incidents are never reported to police. That rate is slightly higher for male victims (63 percent) than for women (59 percent). In the DOJ study, which did not use the word "stalking" in its survey, fewer than half of the respondents who had been victims of stalking behaviors identified them as such.

In other words, victims don't recognize illegal behavior when it comes to stalking. And not knowing that they have the law on their side, they believe they are powerless to stop their perpetrators.

But telling someone "no"—whether it's through ending a relationship, refusing visits or gifts, or simply telling someone to stop following, calling or e-mailing you—escalates harassment to the crime of stalking when that person refuses to stop.

"Once you tell a person ‘No. I don't want to be bothered; we're done; our time is over,' that's when it becomes stalking. Even though they haven't been violent, continued telephone calls, text messages, e-mails, just all of a sudden showing up ... that's stalking, even if it's passive." Scott said, calling it "assault by creating fear."

Not all stalkers make overt threats to their victims, but about 43 percent do. The types of threats range from saying he or she will kill, hit, slap or harm the victim in some way, to say he or she will kill him or herself, to harming the victim's family, friends, co-workers or even pets. About a quarter of those who stalk will also damage a victim's property. Identity theft is not uncommon.

"Many times, once we bring a victim into shelter, we'll start to see abusers start to stalk her family. Many times, it will be her parents," Middleton said, recalling a case where the abuser broke into the victim's parent's home. "... We also see these offenders stalking other family members, even pets. We had one guy who would shoot at a victim's horses, literally trying to terrify her horses. If he can't get to the victim, a lot of time it will bleed over into the family or the pets."

Their children bound Klasky and Graham together, even as Graham's stalking behavior grew progressively worse. After he handed Graham a contempt citation for violating the protective order in March 1988, a judge ordered that Graham and Klasky had to exchange their boys for visits in front of the Pascagoula Police Station on Live Oak Avenue.

News reports of the time say that Graham attacked his attorney, Richard Hamilton, now deceased, when he lost a case. Graham wanted a refund of what he'd paid the lawyer.

By far the most common scenario for stalking is when the victim and perpetrator have been intimate. Three out of four victims know their stalker in some capacity, and incidents of stalking are highest for divorced or separated couples. About a third of stalkers become violent in some way, with about 20 percent using a weapon. Twenty-one percent of victims report being attacked by their stalker. Of men who murder their ex-wives or ex-girlfriends, most—approximately 75 to 90 percent—stalk their victims before killing them.

On July 22, 1988, Graham was hit with another contempt citation for harassment. Moving beyond following and calling, he began spitting on Klasky's car and the cars of her friends and family. This time he spent a few months in jail.

Pure Terror

On April 7, 1989, a sunny Friday morning, Klasky drove her mother, Barbara Klasky, who didn't drive, to the hair salon. It was promising to be a beautiful spring day, if a little chilly. Temperatures were struggling toward 70 degrees.

It was just over three years since she had separated from Graham; the third anniversary of their divorce was still a few months away. Klasky's friends speculate that Graham's behavior may have been getting too extreme even for his family. Just a day or two earlier, one of Graham's brothers filed a mental writ to have him committed, but the sheriff's department couldn't find him.

By that time, Klasky's life had turned into a nightmare of constant harassment from her ex-husband, and she went to great lengths to try to avoid him. She knew that he had guns, and he'd threatened to kill her many times. At 33, she was back living in her parent's house with her two boys, afraid to live on her own.

The one overwhelmingly common element of stalking victims is terror. Stalking victims never know what to expect from their perpetrators and whether their behavior will become violent. And not knowing is terrifying.

Stalking victims often report symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder: anxiety, mild to severe depression, social dysfunction, sleeplessness and nightmares. Experts call the combination of stress-induced ailments "inescapable shock trauma," because of its immediate nature, and because victims are unable to stop or change their perpetrator's actions. About 30 percent of female victims and 20 percent of male victims end up in psychological counseling.

Graham's relentless, long-term and escalating pattern of stalking is textbook behavior: On average, stalking continues for 1.8 years. When the stalker and victim have been intimate partners, stalking goes on even longer, for an average of 2.2 years. About 11 percent of victims in the DOJ study experienced stalking for five years or more. More than a half of stalking victims say they have lost time from work, and about of a third of them said they were afraid the stalking would never stop. People move, change phone numbers and more to get away from their stalkers.

Around 10 a.m., Klasky dropped her mom back at the house and left to go to work at Brumfield's on Delmas Avenue where she was a buyer. As she sat in her mother's big black sedan on Jackson Avenue waiting for the light at Pascagoula Street to change, Graham pulled his familiar baby-blue Ford F-150 pickup truck up beside her driver's side door, in the lane meant for oncoming traffic.

Without hesitating, Graham propped a 12-gauge shotgun in the open window of his truck's passenger side and pulled the trigger. Hit at point-blank range in the left temple, witnesses say the blast blew Klasky's face off. Her attorney, Jack Pickett, whose office was nearby, did not recognize her. Her father, Lyle Klasky, his store just a couple of blocks away, identified his daughter at the scene.

After three years of stalking and harassing, Michael Graham had made good on his promises. Adrienne Klasky was dead.

Postscript

Graham calmly drove from the crime scene to his attorney's office, who convinced him to turn himself in to police. He was convicted of murdering Klasky Oct. 10, 1989, and received a life sentence.

Heartbroken, Klasky's mother, Barbara Klasky, passed away 10 months after the murder at age 65. Her father, Lyle, died in 1998 at age 77.

"I saw my grandparents age 20 years overnight," Northern said, later adding, "He destroyed my family."

Northern, a 17-year-old high-school junior at the time of the murder, and her mother, Klasky's sister Sydney Klasky, helped Klasky's parents care for the couple's children. Sydney died in 2002, the day the youngest boy graduated from high school. Both boys are currently successful businessmen and are doing well, Northern said. "They want to forget about it."

Graham received three parole hearings, in 1999, 2001 and 2003. At each of the hearings, Klasky's friends and family testified, urging the parole board to keep him behind bars. Graham attempted to sue the people who testified against him, the Mississippi Press Register, then-Gov. Kirk Fordice and a handful of others for slander and defamation of character.

On April 14, 2004, the Mississippi Department of Corrections transferred Graham to the Governor's Mansion as a trusty, duty generally reserved for inmates with good records after conviction.

Four years later, on July 19, 2008, Gov. Haley Barbour commuted Graham's sentence, effectively setting him free on parole through an indefinite suspension of his life sentence.

Barbour did not contact the parole board or any of Klasky's friends or family prior to his decision, and although many of Klasky's friends and family—including her son, Michael—pleaded with the governor to reverse his decision through letters and calls, Barbour has never personally responded to any of them, nor to any media requests, to this day.

Barbour's spokesman Pete Smith said at the time that Graham "performed well and (proved) to be a diligent workman" at the mansion.

Although the MDOC does not release the whereabouts of its parolees, Klasky's friends and family believe Graham currently lives in or near Jackson or Hinds County, possibly in Ridgeland.

Mississippi Rep. Brandon Jones, D-Pascagoula, was 12 years old the day Graham murdered Klasky. As a result of the community's outrage over Barbour's decision, Jones has become an outspoken opponent of domestic violence, authoring several bills toughening Mississippi's laws protecting victims, including the stalking law mentioned above.

"The more people are aware of domestic violence and stalking and stalking laws and what to do—maybe it won't happen to someone else," Northern said. "... I just can't believe Barbour did what he did. I'm disgusted with him, just disgusted."

What Is Stalking?

Stalking and domestic violence are about power and control. No one who truly loves someone else will purposely hurt that person or make him or her fear for their life. No one has the right to terrorize or hurt you. "Everyone should be treated with dignity, fairness and respect," said Lt. Tammy Gaines of the Hinds County Sheriff's office.

Here are a few of the behaviors associated with stalking:

• Following, whether physically or through cyberspace with GPS tracking.

• Obscure behaviors, such as rearranging items, just making sure the victim knows the stalker is out there.

• A person gives you flowers or gifts, even after you tell them you're not interested and refuse other advances.

• He or she calls or texts you several times a day and won't stop.

• A person seems to consistently show up in places you go: restaurants, clubs and other social events. Coincidence? Maybe not.

• You find him or her waiting for you in places you frequent, such as your workplace or a child's day-care center.

• He or she has information about you that isn't widely known. For example, he tells you what you wore last night or what time you got home, although you never saw him.

• Posting private or intimate information or photos on social-networking sites. Note that cyberstalking carries additional felony charges and even tougher penalties.

For more information, see the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence website (ncadv.org) or contact the Mississippi Attorney General Domestic Violence Division at 601-359-4251. To report possible cyberstalking, call 601-576-4281. If you are in immediate danger, call 911.

Stay Safe

If you are being stalked, know that you have the right to live without fear in your life. You have the right to request law enforcement protection and to seek a protective order from the courts. Keeping yourself safe means putting distance between you and your stalker.

If you are in danger, call 911.

• Take it seriously. Stalking can become lethal.

• Don't be ashamed to report stalking. A lot of people are embarrassed, but stalking and domestic violence can happen to anyone. It is not your fault. In Hinds County, contact the victim's assistance program (601-974-2933) for help in acquiring a protective order and to provide other support as necessary. Even if you suspect it, call. "If you think you might be (being stalked), don't ignore it," Heather Wager says.

• Document everything. Keep track of the dates and times of the events; note what was said, if anything, and exactly what happened. Get names and contact information of any witnesses.

• Tell your friends and family what's going on. Give someone close to you your schedule and tell him or her when you will be doing something unusual.

• Tell your employer. Give him or her a photo of your stalker if possible, so that your stalker can be evicted from the premises, if necessary.

• Try to change your routine and your travel routes to and from work and other regular stops.

• Do not speak to your stalker. If necessary, change your phone number and e-mail address.

• Do not "friend" anyone you don't know on social-networking websites.

• Find someone knowledgeable about domestic violence and stalking who can help you through it, whether a social worker, an attorney or both.

• Get support from people who have been there. It can be an ordeal. Join a support group if possible.

• Prepare an emergency escape plan for you and your children, and have a safe place to go if necessary.

For additional information, call the Domestic Violence Legal Help Line at 877-609-9911 or the National Hotline for domestic violence at 800-799-SAFE (7233).

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.