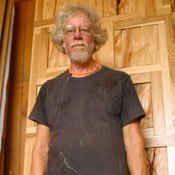

Fletcher Cox is finishing a pair of doors when I visit his shop on a rainy Wednesday. They're the last in a set of 13 pairs that he's been commissioned to make for the new federal courthouse under construction in downtown Jackson.

The doors are pecan, a frame-and-panel construction with two columns of square panels on each one. It's easy to imagine them as elegant, sober barriers to courtrooms and judge's chambers. But there's a playful aspect to the doors that cuts against rigidity. The square panels are offset slightly, and Cox will affix rough, unfinished squares of pecan that look like a split log in those spaces.

When the paired doors hang together, they'll be "bookmatched," so that the staggered columns mirror each other.

Cox harvested the wood for these door panels himself, starting two-and-a-half years ago with a pecan tree cleared from the courthouse site itself. All the trees he used had either blown over or been cleared already. After drying the wood, he began assembling the doors in January. The panels that look unfinished aren't actually so—he removed loose pieces and splinters, first by sanding and eventually with tweezers. The "natural"-looking pieces actually required more work than the planed, regular ones.

It's an irony that Cox appreciates: His woodworking is one long attempt to reconcile the natural and the man-made.

Building a Reputation

Cox, 67, wasn't always a master craftsman.

Born in Williamsburg, Va., Cox grew up near Richmond, the son of a journalist and an English teacher. Neither parent was a true artisan, but his father was handy and made some of the family's furniture, Cox says.

"It was very IKEA-looking stuff, but that wasn't around in those days, so I give him some points," Cox says. "He used particle board, which was thought of as a cheesy material, but he made very simple cubes out of it and painted it with enamel, so that all the cheesiness turned into this lovely texture. It was a pretty good idea."

Cox liked drawing and tinkering but never pursued either formally and headed off to Columbia College, in New York City, planning to study marine science. He loved microscopes and the undiscovered worlds in drops of seawater, he says.

At college, he discovered that he loved to read, eventually graduating with a degree in English and comparative literature. His future wife, Carol, was the graduate English secretary and sat at a desk across from his favorite professor's office. After graduation, he convinced Carol to head west with him. He wanted to go to Seattle, but they only got as far as Wyoming, where he taught high school and junior high science for two years before the winters drove him away.

Carol grew up in the South, moving to Jackson when she was 14. The couple moved to Tougaloo in 1973. That same year, the pair visited the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian had just opened the Renwick as its new museum dedicated to crafts, and the gallery's inaugural exhibit, "Woodenworks," stunned the couple. The exhibit featured innovative wooden furniture by five artists who would become the progenitors of a resurgence in American hand woodworking: George Nakashima, Sam Maloof, Wendell Castle, Arthur Espenet Carpenter and Wharton Esherick.

"We were both tired of working with words," Cox says. "We both looked at it and said, ‘Maybe there's a life here.'"

Cox apprenticed himself to a furniture repairman in west Jackson. Working amid a mountain of chairs and tables, Cox did little more than strip furniture for nine months. He studied how pieces were put together, though, and learned how to sand. He also visited Jackson public libraries and read all the woodworking books he could find—about six, he estimates.

The couple started woodworking together in Tougaloo and brought their tables, boxes and bowls to regional craft shows. Through shows, Cox picked up commission work crafting altars and other religious objects.

By the late 1980s, Cox had developed a reputation for his woodworking. In 1989, then-Gov. Ray Mabus enlisted him to lead a team of master craftsmen—glassworkers, metalworkers and other woodworkers—to add and enhance architectural details to the governor's mansion. Cox worked on the mansion's ceilings, railings and columns.

"His idea was that if we could make a display of craftsmanship made by Mississippians, that it could be convincing manufacturers who were interested in moving here, that we do in fact have a trainable, skilled labor force," Cox says.

Subsequent governors were less enthusiastic, though, and had much of the work removed and sent to storage by the state Department of Archives and History. Cox has used grant money to plan for refurbishing some of the pieces, which have been transferred to the Mississippi Arts Commission, and he hopes to get a larger project grant from the commission in preparation for public displays around the city.

In 2006, Cox won a Governor's Award for Artist's Achievement.

For more than a decade, he has shared shop space with a crew of other local woodworkers, carpenters and designers: Bill Rusk, David Thomas, Kevin Herrington, Joe Partridge and Jeff Goodwin. The group started working together in 1996, sharing a space in the Millsaps Arts District, but they moved to their current barn-like warehouse off Highway 80 six years ago. They share large equipment—sanders, planers, band saws—and help each other with heavy lifting.

Goodwin, an architect who operates his own residential design-build firm, first met Cox in 1994, at Mississippi State University's fifth-year architecture program in Jackson, when Cox was a visiting professor there, doing design critiques. Goodwin had worked his way through school as a carpenter, and he found in Cox the inspiration to ignore the conventional track for architecture-school graduates.

"It was Fletcher that basically said that the vanilla path isn't the only one," Goodwin says. "He did it by example. He gave me the courage to stick to the path, the artistic pursuit, the whole, hands-on notion of it."

In Goodwin's practice, he designs projects and puts them together himself. When he was starting, Cox helped connect him with clients and patiently answered questions, though Goodwin admits he "pestered the hell out of him."

Cox works almost exclusively on commission now. He treats a client's request like a puzzle, using early interviews to discern the essence of a piece.

"I did a conference table for a small law firm, and in the course of the conference with the partners about what it was going to be, one of them said, ‘It has to be wide enough so that if the guy on the other side goes for me, I can get away from him,'" he says. "That gives me a dimension for the top, but it also gives me an idea about this conference table as being a zone of confrontation."

Cox devised table legs that tilt toward each other, a pose that could either look antagonistic or conciliatory. For a material, he picked cherry. The black cherry that grows in the south is dark, streaked with minerals and full of character, he says. It tends to grow faster and in the open, developing branches lower in the trunk.

"I really cannot design anything without knowing what species I'm working in, because they feel so different that they lead to differences in shape and proportion," he says.

Tree and Board

"Starting with a tree is quite different from starting with a board. The wildness lives on in the wood," Cox once wrote in an artist's statement.

For the past 20 years, off and on, Cox has been working on a series he calls "Raw and Cooked." The works—coffee tables, cabinets, doors—attempt to reconcile the properties of wood as it exists in nature with the demands, both aesthetic and functional, of people.

The project came to him first as a problem. On a cross-country road trip, Cox was mulling over his profession, when he had an epiphany. "I realized with great sorrow that I would never make anything as beautiful as a tree, especially the tree that died to provide me the wood to make something not as beautiful as what was killed," he says.

"So I spent a couple years trying to get over that thought, and then it sort of morphed into ‘Well, what about it? What about the tree and the board? How can we think more creatively about it and less despairingly?'"

The question led Cox to "Raw and Cooked," a theory about the line separating man and nature, about how it's largely imaginary. He blames Rene Descartes, the 17th-century French philosopher and mathematician—of Cartesian geometry and "I think, therefore I am"—for introducing that false dichotomy.

"Wood as you find it, it's very shapely, it's sinuous, it's sensuous," Cox says. "Wood as you buy it in boards—once you sand it up, you've basically got a two-dimensional graphic representation of wood on a Euclidean solid."

The furniture pieces join the wobbly, gnarled shapes of wood as it comes from trees—its "first nature," as Cox puts it—to finished, planed pieces in regular, artificial shapes—"second nature." The flat top of a coffee table might start square at one end and taper to a point where the board splintered off the log. Cox sands the pieces so that the "raw" and "cooked" elements blend into one another.

"There's kind of an instantiation of a unity there between first nature and second nature that sort of gives the lie to Descartes," he says.

For Goodwin, who named his first child Fletcher in Cox's honor, his mentor's work is a source of continual awe.

"He can make a natural piece of wood, and a milled, machined piece bleed into one another, and you can't decipher it," Goodwin says. "It's almost like the organic and the manufactured are blurred. He'll take classical notions of proportion and detailing, and he'll dissolve them basically, back into organic shapes. It blurs style and tradition and just washes it with this timeless effect."

For all his ease with big ideas, Cox sometimes struggles—or refuses to explain—his creative process. When I ask him whether he finds any difference in making secular and religious objects, he says he doesn't know how to answer the question.

"I'm confused about the relationship between idea and design, because a lot of design work is felt," he says. "It's inarticulate, the same way that writing a poem is, in a funny kind of a way, inarticulate. My wife, who's a poet, says, ‘You feel something moving up and you try to throw a net of words over it.' So the net of words is ostensibly articulate, but the feeling you're trying to get to—she says the net is never as good as the feeling."

Cox goes back to sanding the last set of doors. When he's done, he'll slide them onto a vacuum table and attach the rough square panels with epoxy. Every piece that goes into one door has a corresponding letter and number label, written in neat pencil—horizontals start with a letter, verticals start with a number. When it's time, he'll button up the plastic envelope surrounding the table and flip on the vacuum pump, using 14.5 pounds per square inch of pressure to hold the pieces in place while the epoxy sets. There's no margin for error.

A newspaper clipping pasted on the I-beam behind the vacuum table reads, "Fletcher Super, But Not Enough." It's about a (football player), he says. There's a running back out of Yazoo City that has bumped him from first place on a Google results page for his name, he says with a rueful grin.

"With all of these arts, if you're going to be good, it just gets harder as you go on," he says. "The technical stuff gets easier: As you learn to anticipate where your opportunities to screw up are, you can take steps to forestall screwing up, so you spend much less time repairing mistakes. But the design stuff, the creative part gets harder and harder, because the bar gets higher and higher as you raise your expectations."

For more about gallery openings and local artists, be sure to check the JFP Events for upcoming events, as well as the Arts & Culture Blog for more culture shock(ing).

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus