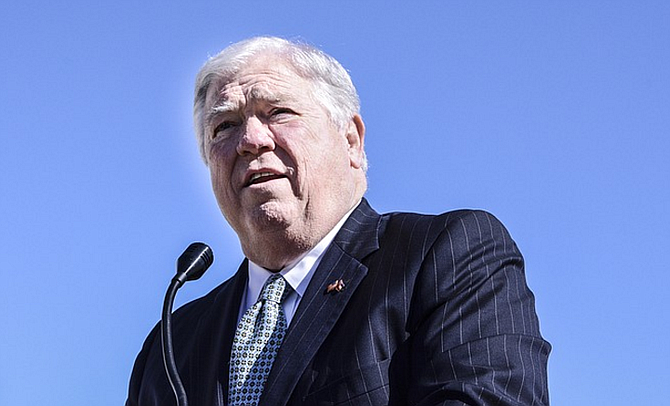

Corporate lobbyist Haley Barbour came home to Mississippi and served as governor from 2004 to 2012, then returned to Washington, D.C., to lobby again. While he was in his home state, he led the effort to bring tort-reform relief to corporations and limit damages. Photo by Trip Burns.

It sounded mighty convincing: "Mississippi faces a crisis in medical malpractice insurance." The warnings by industry have been dire: "This is a wake-up call for Mississippi." The reports of doctors bolting the state have been breathless: "It's the harassment of dealing with meritless lawsuits." When the tort-reform hysteria blew up in 2001, Mississippi, it seemed, was finally on top of something: The state's "trial-lawyer cabal" was harnessing "runaway juries" willing to mete out "jackpot justice" and drive all our good doctors and job-producing businesses out of "lawsuit central" (the state).

To hear the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the insurance industry tell it, we ignorant Mississippians were (and still are) suing each other so much that doctors and businesses cannot afford the outrageous insurance rates they need to protect themselves from our damned lawsuits. Rich trial lawyers were trolling the hospital wards looking for ways to bilk the rich doctors. The only way to limit such treachery was to limit Mississippians' right to sue and collect damages from companies and physicians. The result: Mississippi's Legislature enacted a $500,000 cap on non-economic damages, along with other reforms meant to curb malpractice rates and keep doctors in the state. Crisis averted.

Or was it? Indeed, was the legal crisis even real? Or did the state fall prey to one of the best-funded hoaxes of recent times?

Manufactured Crisis

So far, the debate over tort reform in general, and medical malpractice specifically, has been cast largely as evil lawyers vs. virtuous doctors. Being that people generally need a doctor more often than they do a lawyer, many people have joined the latter camp by default. Bolstered by urgent press reports, many Mississippians have easily bought the line—without much evidence—that doctors are flooding out of the state due to outrageous malpractice verdicts, which in turn lead to exorbitant insurance rates for them. And even when trial lawyers have responded that evidence of that is shaky at best, their credibility has been strained. After all, who can trust lawyers?

In truth, on at least some of the counts, the trial lawyers have been right all along—and unbiased evidence is starting to mount to prove it. In August, the General Accounting Office of Congress released a pivotal 58-page report, "Medical Malpractice: Implications of Rising Premiums on Access to Health Care," prepared at the behest of three Republican congressmen who support federal caps on liability. To their credit, the three men—James Sensenbrenner Jr. of Wisconsin; Billy Tauzin of Louisiana and Steve Chabot of Ohio—wanted to know the facts behind the hype as Congress wrestles with the question of federal tort reform, which ironically is a pet project of the "state's-rights" GOP.

The report focused on five states that industry has identified as "crisis" states for medical liability and doctor flight: Florida, Nevada, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Mississippi. The GAO, the nonpartisan investigative agency of Congress, did the most extensive study to date of the medical climate in the target states, comparing them to four states not identified by industry as "problem" states. After conducting interviews and corroborating reports of doctors leaving and reducing services due to the legal climate, the GAO found that the medical malpractice climate has been dramatically overblown by lobbyists and the media in those five states.

The report sought evidence of the frightening claims that doctors were leaving in droves and substantially reducing services in order to avoid potential lawsuits. "[M]any of the reported provider actions were not substantiated or did not affect access to health care on a widespread basis. For example, some reports of physicians relocating to other states, retiring, or closing practices were not accurate or involved relatively few physicians," the August 2003 report stated.

It further found no major reduction in medical services in the target states due to physicians worrying about them being particularly risky for lawsuits. It confirmed that while some physicians had left, evidence didn't support that the movement was due overwhelmingly to malpractice risks; in fact, the level of medical care in the "crisis" states was largely unchanged. For the most part, when doctors left, others took their place, and in many cases the hospital or clinic started absorbing more of the cost of malpractice insurance to take the onus off the doctors.

Magnolia Exodus?

In Mississippi, for instance, the GAO found no mad "exodus" of doctors, despite dire media reports, such as a Delta Democrat-Times editorial: "All over Mississippi, there have been reports of doctors closing shop—leaving the public at increasing risk—because the price of healing the sick has become prohibitive," the conservative paper declared.

Indeed, in all five "crisis" states, such hyperbole tended to be just that—overblown. "Although some reports have received extensive media coverage," GAO wrote, "in each of the five states we found that actual numbers of physician departures were sometimes inaccurate or involved relatively few physicians." In Mississippi, for instance, the reports of doctors packing up their practices were loosely scattered around the state and, in fact, represented only 1 percent of all licensed physicians here. "Moreover, the number of physicians per capita has remained essentially unchanged since 1997," the report stated about Mississippi, adding in a footnote that the number of doctors here actually increased between 1997 and 2002, from 1.9 to 2.8 per thousand in the population.

This, of course, isn't what we've been hearing the last couple years. Jackson doctor D. Kyle Ball spoke on behalf of his peers in a Clarion-Ledger op-ed on June 3, 2002, calling the malpractice crisis a "brain drain": "These men and women have been forced to make radical changes in their life's work. Many have refused to accept any new patients; many have begun limiting the scope of their medical practice; and many others have elected to retire."

The GAO found isolated incidents of doctors offering fewer services due to the threat of liability, but mostly in rural areas where other factors also affect a doctor's desire to stay. The report cited the example of pregnant women in Central Mississippi who have to travel 65 miles to a hospital to deliver a baby because family practitioners at their local hospital have stopped performing obstetric services due to high premiums. "In both areas," the report added, "providers also cited other reasons for difficulties recruiting physicians to other rural areas."

Malpractice insurance rates have increased dramatically in some states since the late 1990s, GAO found; in 2001 and 2002, rates for general surgery, internal medicine and obstetric/gynecology increased 15 percent nationally and over 100 percent in some states, including Mississippi. And the investigators said that rates of malpractice growth have been slower on average in states, such as Mississippi, that have enacted caps on pain-and-suffering damages—but the rates did continue to rise, 10 percent in states with caps, as opposed to 29 percent in states without. But the GAO warned not to spin that finding too loosely: "[T]he averages obscured wide variation in claims payments and rates of growth across states and over time," it said. This state saw an 18-percent decrease in claims payments from 1999 to 2000, a 61-percent increase in 2001 and a 5-percent decrease in 2002. Premiums also vary widely by specialty and geographic area.

The report strongly reiterated its findings from a June 2003 study that rising malpractice insurance rates are based on a number of factors. The greatest single factor appears to be increased losses for insurers based on paid malpractice claims, but the GAO said the lack of comprehensive data made it difficult to perform a full analysis of those claims. Secondly and confidently, the GAO pointed to bad investments that the insurance industry made from 1998 to 2001 "as interest rates fell on the bonds that generally make up around 80 percent of these insurers' investment portfolios." Thus, income from premiums had to make up for a larger share of the insurers' costs. Third, insurers "competed vigorously" in the boom-time '90s, offering off-the-rate-card prices that did not cover losses as the economy stalled. Fourth, in 2001, reinsurance rates increased more rapidly, in part because of an insurance industry push to make policies more profitable.

To put it simply, the insurance companies were paying out larger malpractice claims, particularly in 2001, but they were also raising rates to make up for flailing investments and less-profitable policies written in boom times. As premiums went up, doctors, legislators and reporters could believe there was a legal "crisis" brewing.

California Dreamin'

The GAO conclusions, which appear balanced between the doctor-vs.-lawyer "sides," come as a relief to some Mississippi trial attorneys, who feel they have been unfairly vilified in the insurance industry's attempts to recoup its losses. "I read the report as affirming what I said back during the (2002) special session about some of the claims the tort-reform lobby was making," said David Baria, a Jackson attorney and former president of the Mississippi Trial Lawyers Association. Baria has said often that bad investment decisions were a major factor in the rate jumps. "Yes, there is a crisis; it's always a problem if rates triple or quadruple overnight. There's always disagreement over whether litigation drove the increases or caps reduce them."

In fact, damage caps have not proved to be the panacea that industry likes to say. States around the U.S. that have instituted liability caps have often found that rates have kept rising and some malpractice insurance providers have kept leaving, as in Mississippi, leading to the conclusion that something else might be at play. Like fierce industry competition, or worse.

California is a case in point. Interestingly, that state is the poster child for many advocates of medical-liability reform. In 1975, the state instituted $250,000 pain-and-suffering (non-economic) caps in response to the first round of spiking malpractice rates in the U.S. Fast forward 28 years, and California's rates are still high, but more stable than many other states.

"You can look at caps and see the way they work," said David Clark, an attorney and partner in Bradley Arant Rose & White, major backers of tort reform in Mississippi. "Look at California 27 years ago; they were running into a crisis. When they imposed $250,000 caps on damages, it brought them back from by far the highest to back in line."

The problem with that example, repeated incessantly by tort-reform supporters, is that a major piece of the puzzle is left out. In fact, after California capped damages, its rates kept shooting up—increasing 190 percent between 1976 and 1988. Californians, in the way that they do, got mad and demanded insurance reform. In 1988, they passed Proposition 103, mandating oversight of insurance companies and state approval of premium rates.

When asked about that part, Clark expressed disbelief that the insurance reforms even happened in California, not believing me until I read him several different news reports out of the thousands about Prop. 103 that are available in the Nexis database. "I never heard about it," he said of the insurance reforms.

If that's true, it might speak to the poor media coverage too often given to vital issues in the civil-liability debate, as referenced in the GAO report. My search of the Nexis database, for instance, turned up no mentions of Prop. 103 in Mississippi press stories that otherwise focused on California's damage caps.

Indeed, an Aug. 12, 2002, Clarion-Ledger article by Jerry Mitchell, headlined "Calif. Held Up As Tort Model," simply left the pivotal point out. Starting out saying that Mississippi's medical malpractice premiums were "skyrocketing 400 percent," Mitchell wrote, "It's also what took place three decades ago in California." He wrote about Gov. Jerry Brown's special session in 1975 to cap non-economic damages, along with other legal reforms.

Then, he wrote: "Since the reforms, premiums have risen 167 percent compared to 505 percent nationally, according to a 2000 study by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners." He quoted Hattiesburg doctor George McGee saying, "California is a glowing success." He quoted David Baria saying that the average malpractice payout per doctor in California is $55,000, but that premiums haven't fallen. And he said that California's average premium of $25,451 is higher than the national average. But he did not say that Californians had rebelled against the insurance industry, and sternly regulated it in 1988—a move widely believed to have kept rates "only" up 167 percent, as opposed to twice that or more.

The Clarion-Ledger used the California example several times in editorials calling for non-economic caps, but without bringing in its insurance-reform component—a breathtaking factual omission, considering that national media around the country have repeatedly reported Prop. 103's role in California's saga.

Media Complicity

Indeed, many opponents of tort and medical-liability reform see corporate media as a co-conspirator with industry, whether on purpose or by simple confusion over the dense issues involved. The GAO warned that media reports on medical malpractice are often faulty or overblown—an objective assessment that makes the state's beleaguered trial lawyers cheer in response.

They say the Mississippi media have been lazy on the topic, and are easily fed incomplete data. Trial lawyer Jim Kitchens of Jackson said in an interview earlier this year that industry has used the state's journalists to pound a "steady rhetoric": "I've never seen such a sustained media campaign about anything."

That may sound like spin, but an analysis of state print media of the last two years shows that "greedy trial lawyers" have overwhelmingly bore the brunt of bad media during the tort-reform debate. They are often interviewed, or disparaged, in stories filled with exaggerated catch phrases like "jackpot justice," "runaway juries," "lawsuit central," and others—disturbing characterizations by the so-called objective media. News stories and editorials alike often start with a dramatic statement, if loosely supported, about the "crisis" and the miserable legal climate for doctors.

This demonization of the trial bar is nowhere more apparent than in the Clarion-Ledger, a statewide newspaper. Starting with Jerry Mitchell's June 27, 2001, front-page article, "Hitting the Jackpot," the daily newspaper has been relentless in its pursuit of a malpractice legal "crisis" in Mississippi. June 29, 2001: "More insurance firms exit Miss." Aug. 22, 2001: "Hitting the Jackpot in Mississippi." Oct. 30, 2001: "Staggering jury verdicts draw calls for tort reform."

Since June 7, 2001, the newspaper has used the phrase "jackpot justice" at least 47 times in articles and editorials, according to a Nexis search. On Aug. 2, 2002, Mitchell began a news story: "Doctors begged, businessmen pleaded and citizens cried for lawmakers Thursday to reform the civil justice system." He and other reporters wrote myriad articles about doctors pressured by high rates, often with large photos of them with young patients: "Medical malpractice lawsuits pushing doctors over edge" and "Surgeons ready to walk off job" and "Tort reform: Just what the doctor ordered?" Usually, trial attorney responses came near the end of the piece, and seldom were everyday citizens interviewed.

Likewise, the paper's editorials beat a steady drum of panic: "Mississippi faces a crisis in medical malpractice insurance" was a typical lead sentence, or "End non-economic award jackpot" or "Medical insurance issues pressing." Most editorials seemed determined that the newspaper be given full credit for uncovering the "crisis," referencing Mitchell's 2001 "jackpot" series at every turn. For example: "As revealed last summer by The Clarion-Ledger's series 'Hitting the Jackpot In Mississippi Courtrooms,' the Magnolia State has become a mecca for out-of-state lawsuits leading to a perception of an out-of-control legal system." Whether or not that "perception" was a reality was an issue the paper did not explore in any depth.

Much Mississippi media, including the Clarion-Ledger, have often displayed disdain for the state's juries, lumping them into a Grisham-esque monolith. "The greatest wildcard on runaway juries is the 'pain and suffering award," where emotional appeals can turn reality upside down," the Clarion-Ledger opined Aug. 26, 2002. (The GAO found that average malpractice verdicts are $500,000, settlements $300,000—far from the outrageous millions that industry reps like to claim. And most large verdicts are dramatically reduced before actually being paid—something few media reports get around to mentioning.)

Some Clarion-Ledger critics like to say the seemingly pro-reform reporting is because its parent company Gannett is a major corporation, and thus it wants corporations protected from lawsuits. But that doesn't ring entirely true; the Gannett News Service conducted a study of "crisis state" Florida's malpractice rates, finding that they cannot be blamed on high jury payouts. "[T]here is no malpractice crisis in Florida's courts," Paige St. John wrote in Gannett's Pensacola News Journal on March 15, 2003. But that in-house study has yet to make it way into the pages of the Clarion-Ledger.

One reporter, Joey Bunch of the Sun-Herald in Biloxi (who has since left the state), provided a notably balanced and informed voice on the issue. During the special session, called by Gov. Musgrove in fall 2002, Bunch gave all the players equal voices, including patients like Dawn Bradshaw of Brandon who entered the hospital with mild pneumonia and left as a brain-damaged paraplegic and later won $9 million in compensation. He only used "jackpot justice" once in print in the dozens of his articles on the topic I found. He also criticized the trial bar, as well as the medical lobbyists and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—the 500-pound gorilla radiating much of the hype.

A Political Wedge

This battle didn't begin in 2001, or in Mississippi, or even in doctor's offices. The medical-malpractice debate is just one more front, and doctors an unfortunate pawn, in a 30-year political battle in Washington between corporations and trial lawyers.

The July 12, 2003, National Journal reports that the stakes are higher than one would think by reading frenetic "jackpot justice" diatribes in local newspapers. "Republicans, in control of both the White House and Congress, are working hand in hand with their corporate allies on a carefully developed and well-financed campaign to battle trial lawyers. If successful, the GOP and the business community could realize two long-sought goals: to revamp some of the country's tort laws, and to weaken a primary funding source for the Democratic Party," wrote Peter H. Stone.

Trial attorneys are, indeed, one of the few ultra-wealthy groups in the U.S. that routinely still give money to Democrats (from 1999 to 2002, 89 percent of trial-bar donations went to Democrats, the Center for Responsive Politics reports). And Republicans don't like that. They also want to protect big business from having to pay out large sums of money in liability trials. Citizens' groups and trial attorneys argue that the courts are a necessary recourse to police corporations that hurt or kill people with their products. If damage pay-outs are limited, the incentive to put out dangerous products is more tantalizing. With caps, the reform opponents argue, companies can just build smaller settlement projections into the budget plan.

The strategy that industry has followed, as outlined in National Journal, is fascinating. First, they battled over no-fault auto insurance in the 1970s, then broad product-liability reform in the 1980s, but without great successes. In the late 1990s, though, industry hit its stride, especially after lobbyist Tom Donahue became president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in 1997 and formed the Institute of Legal Reform, which spent $23 million in 2002 lobbying in Washington and various states. Suddenly, industry and the U.S. Chamber went on the attack—and strategically moved medical malpractice front and center. Everyone loves doctors.

And the strategy is working, especially as media around the U.S. buy into the scheme or under-report the story. Many moderate Democrats are shying away from candidates supported by trial attorneys. President Bush and right-hand man Karl Rove have long pushed the tort-reform political wedge strategy. Bush said in Mississippi last year, "There are good docs who can't get liability insurance or (have) given up their specialties or (are) leaving their practices to go somewhere else. It's estimated by some that this great state could lose 10 percent of your physicians, unless you do something about it." He said that "these lawyers will sue everyone" in a "giant lottery" with "lousy juries."

David Clark agreed with Bush's premise that the state's poor legal reputation can cost us businesses, and thus jobs, regardless of the reality or the reason they give for staying away. "It's difficult to measure 'why' when you have businesses that don't come here. If they're influenced by the tort climate, they don't tell you that," he said. When asked if comments such as Bush's are actually talking down the state to potential businesses and doctors, who might be as scared by the myth as the reality, Clark defended the strategy. "It's no secret; we're not out there trying to slam the state."

But slam they have. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce held a press conference on May 8, 2002, in Washington, D. C., to announce a campaign against Mississippi's legal system. It spent $100,000 on ads in the state's newspapers to plead its case for "common-sense legal reforms now." This fall, the Chamber's Institute for Legal Reform plans "get out the vote" drives for pro-reform candidates in Mississippi, according to the National Journal article.

But the Mississippi plan was already well underway. Nearly a year earlier, on July 23, 2001, the Mississippi Manufacturers Association hosted a meeting of trade associations and lobbyists to discuss tort-reform strategy. According to a written summary of the meeting by an attendee, Alabama political consultant George Burger laid out a five-point plan for our state, starting in July 2001, to educate the public, raise money, introduce legislation, defeat anti-tort reform judges in 2002 and then "change the players" in fall 2003 (i.e. defeat anti-tort reform legislators). Clearly, the group is on schedule with its plan of attack.

A Haley Barbour administration seems likely to ensure that tort reform will be front and center. After the U.S. House voted 229-196 to pass a federal medical-malpractice bill with $250,000 caps, last March, industry hired Policy Impact Communications, an arm of Barbour's D.C. lobbying firm, to pressure U.S. senators to vote for the bill this fall. At the moment, at least, that prospect has dimmed.

Holistic Medicine

The medical-reform lobby hasn't been helped much by reports like a Dec. 3, 2002, Washington Post story showing that 98,000 Americans die and a million more are injured due to preventable medical errors that cost the U.S. some $29 billion a year. And a medical blooper like a young woman dying in the Duke University hospital in February after a botched heart and lung transplant is making it harder to sell malpractice reform to the general public, National Journal reported.

The truth is that most doctors are not to blame for these very costly mistakes. Fewer than 5 percent of physicians account for more than 50 percent of malpractice cases—and a movement is afoot to tighten tracking and regulation of bad doctors.

And, if the major media will report it, research like the GAO study may bring this debate back down to earth a bit, perhaps revealing that every trial attorney isn't an ogre and every doctor isn't a saint. (In fact, there are reports around the state of doctors refusing to treat trial attorneys' families.)

Truth is, something needs to be done about insurance premiums for doctors (and then perhaps the rest of us). You can't blame doctors for being outraged at excessive rates, or for believing some very well-orchestrated hype about why rates are so high.

In some states, alternatives to liability caps are being considered. Mississippi may hold hearings to determine why rates are still high and malpractice insurance providers still bolting the state (we're down to one), even after the caps imposed during the special session. Such hearings could reveal that caps need to be balanced with insurance reforms, a la California. "I would ask the Legislature to hold hearings to determine the overall status of insurance providers given the state of the stock market and the fact that we passed substantial tort reform and still had medical malpractice providers leave the state," Gov. Musgrove told me in August. "I believe you will see me deal with and propose hearings concerning this area." That is, if he's re-elected.

David Clark of Bradley Arant disagrees with the hearing idea. "The insurance companies are there; they have to make a profit.…You can't force insurance companies to come in and do business; if they see a viable market for them, I assume they would come in. … I'm not really sure what a state can do to investigate problems."

Industry might not be pleased, but such hearings would be the first step beyond the anger and hysteria, and a move to finding a holistic approach to curing the ills of both the medical and the legal industries.

Perhaps then the people can finally take this debate away from the "doctor vs. lawyer" mythology and, like in California, re-frame it into a more accurate paradigm: people vs. "cap-happy" industry. Perhaps then we can find solutions that demonize neither doctors nor lawyers as a group, and help the people it's supposed to: you and me.

Donna Ladd is editor-in-chief of the JFP.

Note: After this story went to press Monday night, the following story about the GAO report appeared in the Washington Post today (Tuesday). (An interesting Mississippi media tidbit; as of today, no Mississippi media had reported on the GAO findings, although daily news outlets in the other four states examined in the report as "crisis" states had reported it.)

What Crisis? Malpractice Premium Spikes Don't Force Out Docs

Public Citizen consumer report on myths of medical liability claims

Read a June 8, 2003, Tallahassee (Fla.) Democrat story that looks at the caps vs. Prop. 103 reform in California. And this is very interesting, being that industry used California's caps as a panacea for "fleeing" doctors: A 2001 survey of California doctors "found that despite affordable malpractice premiums, 43 percent of the 2,307 doctors polled plan to leave medical practice in the next three years, 58 percent have difficulty attracting physicians to their practice and two-thirds advise their children to avoid the profession. Low reimbursement, managed care hassles and government regulation are their greatest sources of dissatisfaction."

In response to the GAO report (and presumably this story), Sid Salter of the Clarion-Ledger calls critics of media coverage of tort reform "crybabies" in this Sept. 24 column.

Read the JFP's Oct 2. analysis of Salter's "crybaby" column.

Oct. 19, 2003: C-L editor writer Jim Ewing responds to criticism of The Clarion-Ledger's coverage of "jackpot justice."

Nov. 4, 2003: Clarion-Ledger reports on a new GAO report that disputes the "doctor shortage" claim for Mississippi and other states.

Nov. 9, 2003: Clarion-Ledger editorializes that GAO report gives "incomplete review"

Previous Comments

- ID

- 77185

- Comment

- I agree with everything you said. But I think your empahsis (see Magnolia Exodus?) on numbers of doctors who actually have left is on the whole irrelivant and pointless. The percentage per capita of doctors leaving does not reflect the size of the problem. This focus undermines the large numbers of unhappy doctors who continue to work in the state, horrified over the possibility of uprooting their family to continue to live in the exact same lifestyle they have been accustomed. You go on the say that perhaps their moans & crys are justified. Doctors telling the children not to get into medicine does not boad well for the future. Tort reform does nothing for the growing crises of affordable decent healthcare in this country. Its not the magic pill to cure amercian healthcare (nor is keeping doctors fat & happy the answer). It goes deeper than insurance costs. Thats only one of the pending lawsuit concerns that face the fast growing cost of healthcare today.

- Author

- slackmaster

- Date

- 2003-09-17T10:33:35-06:00

- ID

- 77186

- Comment

- Slackmaster, point well taken. Understand, though, that the emphasis on how many doctors have actually left is the GAO report's not mine, and it's in response to the scare tactics from industry. I in no way mean to say that doctors have it rosy; my bigger point is that they are caught in the middle of something much bigger and more complex than how many malpractice lawsuits are filed in Mississippi. We need good doctors (and lawyers), and I suspect that the big tort-reform blow-up is hurting that, while avoiding what the real questions are. I plan to take that up more in future story. I've spent way too long on this now to only write one story! ;-)

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-17T10:43:26-06:00

- ID

- 77187

- Comment

- Bill Read this

- Author

- Bill Guy

- Date

- 2003-09-17T11:42:16-06:00

- ID

- 77188

- Comment

- The Clarion-Ledger finally wrote about the report todayóinside on p. 7, I believe. Note that this story follows the structure I talk about above, and that a story about the myth of doctors leaving still leads with a story about doctors leaving. There are also a lot of holes here, and she sure didn't mention that the report complains about media overblowing the "crisis." You also don't get the report's strong assertion that bad investments by insurance companies is a vital component to high premiums. Daily media in other states examined in the report definitely have given the report more thorough coverage. Clarion-Ledger story about report One thing that struck me as very misleading is the order of the section about the American Medical Association. It reads as if the AMA just told the GAO to hold the report, and it published it anyhow. The truth is the AMA, along with other interested groups, reviewed the report this summer. The AMA is the only one that, predictably, disagreed with its conclusions. It asked GAO to hold the report; then the GAO went back and clarified its research and examined the AMA's complaints, which did not change the findings. The report discusses that in detail, pointing to studies disseminated by industry that show larger numbers of doctors leaving and such that did not stand up under scrutiny because the samples were too small or AMA didn't provide sufficient data for the studies to be fairly reviewed. The point is, GAO dealt with the AMA's concern, and then was confident enough with the strength of its research to move ahead with publishing the findings. Remember: GAO doesn't have a pony in this race. I wanted to talk about the AMA dissension in the piece, but I had to make choices based on space. But it is important to know all this, because the response is surely going to be to point to those AMA-favored studies that have not held up another objective scrutiny. The truth is, these findings are hard to just chalk up to trial-lawyer hype. Y'all can read about all this for yourself in the report itself, linked above in the study.

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-17T13:28:46-06:00

- ID

- 77189

- Comment

- Better late than never: We're happy to see that a Clarion-Ledger editorial today ran an editorial about medical malpractice that was much less frantic than in the past, and talked more openly about some of the points it's glossed in the pastóespecially that doctor's premiums are clearly affected by much more than malpractice suits i.e. bad business decisions on its own part. "Lawmakers could also look more closely at the insurance industry to see if its claims of unprofitability reflect risk or simply bad corporate investments. And they could also review Gov. Ronnie Musgrove's plan for lower rates for doctors who agree to treat patients covered by Medicaid, Medicare, the Children's Health Insurance Program and the state employee and teacher health insurance plan. Malpractice insurance is worth a second look, but maybe not quite in the same way Mississippi physicians demand." Good, but they need to stayon this and help us call for legislative hearings that include serious discussion discussion of insurance reform; insurance companies should not be exampt from anti-trust rules any more than other company should be. And we certainly agree with the C-L that any reforms should include tighter regulation and disclosure of the "bad" doctors who are responsible for the vast majority of med-mal suits. It's unconscionable that it doesn't. To its credit, the C-L has talked about this in the past; Mississippians should not back off the Legislature until this is included. These are our lives that industry is messing with, and profiting on. http://www.clarionledger.com/news/0309/18/leditorial.html The main quibble I have with this editorial is how it starts, probably in an effort to indicate that its call for med-mal damage caps wasn't the wrong decision (which we think it certainly was). They should look closer at California, and get beyond the AMA press release: the rates did not stabilize after the caps. It took Prop. 103, which targeted all insurance companies, to bring some stablization to the market. Prop. 103 was complicated, and controversial, but it did have a visible effect on premiums. The C-L should at least do its typical he-said-but-she-said-type story on 103 and not just ignore that it happened. Public Citizen, which the C-L references in today's editorial, talks about it all the time; why leave it out of the debate?

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-18T12:54:04-06:00

- ID

- 77190

- Comment

- Excellent, well-researched article which exposes every last one of Mississippi's major newspapers for what they are: cheap, superficial propaganda rags, supported by the massive Karl Rove 21st century McCarthyism agenda. The only entity standing in their way is the scrapy consumers advocate: The Peoples' trial bar.

- Author

- peter k. smith

- Date

- 2003-09-18T14:42:00-06:00

- ID

- 77191

- Comment

- I'm delivering a copy of your paper to various members of the press as a gift from me.

- Author

- jp!

- Date

- 2003-09-18T16:49:28-06:00

- ID

- 77192

- Comment

- Bush continued his campaign against trial attorneys in his weekend radio address. Presumably referring to his proposed $250,000 med-cal caps, he said, "I have proposed reasonable limits on the lawsuits that are raising health care costs for everyone." http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/09/20030920.html

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-22T15:26:26-06:00

- ID

- 77193

- Comment

- A letter to the Clarion-Ledger today from the director of the Mississippi State Medical Association perfectly illustrates the spin I talk about in the above story. William F. Roberts tries to discredit the recent GAO findings (although they're not mentioned until the bottom of his letter, and then without defining what the GAO is, although he pointedly says up top that Public Citizen was started by Ralph Nader) by just brushing aside the well-founded (and rather obvious) conclusions that bad investments are in a significant way driving insurance companies' high premiums. In the C-L editorial, which is linked above, the paper rightly followed our suggestion of the day before by calling for the Legislature to examine the insurance industry now that caps clearly aren't working. Roberts writes: "The accusation that high malpractice insurance rates are tied to investment losses was conceived by the trial lawyers." This is simply false: Who should Mississippians believe first: a biased lobbying association or the unbiased investigative arm of Congress? Remember, medical assocations also sing the praises of California's $250,000 caps without discussing voters' move to regulate the insurance industry (one of the few exempt from antitrust laws). It would be interesting to see his response if/when the C-L decides to wade into that particular discussion. Letter: http://www.clarionledger.com/news/0309/23/l01.html

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-23T12:35:30-06:00

- ID

- 77194

- Comment

- don't hold your breath!

- Author

- Jason Pollan

- Date

- 2003-09-24T03:28:52-06:00

- ID

- 77195

- Comment

- Go read what the "Conservative News Forum" is saying about this story over on the Freepers' popular (and infinitely whiny) forum (Free Republic). The comments, at least to this moment, show an amazing lack of comprehension of what is actually in this article (which is posted without permission, of course) or the GAO reports. Most of the comments are useless--just false accusations that the JFP was started by trial lawyers--but I think it's useful for JFP readers to see how this issue is spun nationally by ideologues, and how advocates of tort reform simply want to lump anyone who is willing to look at this issue with fresh and curious eyes (and without a pony in the race) into their neat little evil "trial lawyer" box so they can push our concerns aside. Anyone who knows me knows that I could give a flip about any particular interest group or political party, other than "the people." We have got to pry this discussion out of the doctors-vs.-lawyers paradigm that is obfuscating what it is really going on that affects all of us. http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/986702/posts

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-09-26T10:44:48-06:00

- ID

- 77196

- Comment

- Mississippi legislators pledge to pass more "tort reform": http://www.wlox.com/Global/story.asp?S=1464072

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-10-01T10:58:29-06:00

- ID

- 77197

- Comment

- Here are more good links on the politics (and accuracy of) the med-mal "lawsuit crisis": Washington Monthly: "How the GOP milks a bogus doctors' insurance crisis" http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2003/0310.mencimer.html GAO Testimony, Oct. 1, 2003, "Medical Malpractice: Multiple Factors Have Contributed to Premium Increases" http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04128t.pdf Bill Minor's column: "Where's all this "jackpot justice" that propagandists have been pounding into the heads of our citizens? It's certainly not in Mississippi." http://www.sunherald.com/mld/thesunherald/news/editorial/6911359.htm Finally, here's one from Insurance Journal: "$The U.S. property/casualty industry's net income after taxes rose to $14.5 billion in first-half 2003 from $4.4 billion in first-half 2002, as both underwriting and investment results improved, according to Insurance Services Office Inc. (ISO) and the National Association of Independent Insurers (NAII). Reflecting the industry's income and unrealized capital gains on investments, its surplus, or statutory net worth, increased 9.9 percent to $312.5 billion at June 30 from $284.3 billion at year-end 2002." http://www.insurancejournal.com/news/newswire/national/2003/09/30/32692.htm

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-10-03T14:29:32-06:00

- ID

- 77198

- Comment

- The Associated Press reported today that "tort reform is least understood issue" in Mississippi. The rather he-said-she-said story didn't get deep into the issue, or mention the GAO report (oddly), but it touches on how the issue is being used as a wedge issue in the state, among unsuspecting voters who aren't clear on what it all means: "Tuck, who was a Democrat until last December, tells voters tort reform will ensure them accessibility to health care. She reasons that tort reform is the only way to make malpractice insurance affordable for doctors. Last year, several Gulf Coast doctors walked off the job, saying they couldn't pay for coverage. And some rural communities found themselves in a health crisis after doctors closed their doors citing the inability to secure affordable insurance." http://www.hattiesburgamerican.com/news/stories/20031006/localnews/401226.html

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-10-07T00:15:45-06:00

- ID

- 77199

- Comment

- Wow, another clueless doctor. Rest easy Doc, Ladd will tell you how it really is up there in Kosciusko. She knows more about your business than you do. The experise amongst her and her followers goes very, very deep. They may even be willing to consult for you. They've got ideas how to make less profit or how to get back at your greedy, greedy insurer. Give them a call, or drop them an email, today! Oh, and before I forget Doc, Blackmon was the most qualified for the job despite those two feet sticking out of her mouth. You should have looked past her abysmally run campaign but didn't because of her race. Come clean Doc. We all know why you didn't vote for her. "Kosciusko Medical Clinic's family physicians have been slapped with almost 30 meritless class action lawsuits since January 1, many of which were filed by Blackmon's law firm. As a result of these frivolous claims, the face of health care here in rural central Mississippi has been drastically and negatively changed: # Skyrocketing malpractice premiums have priced us out of the baby delivery business and threaten to whittle away other vital services. # Physicians are being forced to devote an inordinate amount of time answering these false charges instead of providing patient health care. # We are reluctantly being made to dismiss from our care those patients who have filed these suits, many of whom are suing their family doctors. # At least one of our family doctors has left our practice because of this hostile medico-legal environment." http://www.clarionledger.com/news/0311/20/l08.html

- Author

- VBell

- Date

- 2003-11-20T15:06:40-06:00

- ID

- 77200

- Comment

- BTW, to offer better attribution, a good part of VBell's posting above is directly quoted from a letter to the editor of The Clarion-Ledger by Stanley Hartness, a doctor in Kosciusko. I don't know the accuracy of his comments, and The Clarion-Ledger does not seem to factcheck its letters. So everyone should take that into account. That said, the question is not whether doctors are facing a premium crisis -- they are. No doubt. (As are many Americans.) The question is why, and what can/should be done about it. What I would question in Dr. Hartness' letter is his easy causal jump: "As a result of these frivolous claims...." What the General Accounting Office found was (a) high premiums (b) affected IN PART by high numbers of malpractice claims, in addition to (c) risky business decisions made by the insurers and some other important factors (see reports). The conclusion: It's much more complicated than it's been presented by the industry side and the media, as the GAO directly stated. And it makes little sense to draw causal conclusions based on anecdotal evidence or, worse, hysteria being spread by folks with an agenda. What is needed is a well-rounded public discussion (and public hearings) about the whole picture. That hasn't happened, thanks to the political rhetoric involved. And, VBell, I've had doctors tell me they believe they've been snookered by industry on this issue. It's not about being "clueless," as you so eloquently put it, it's about being too busy healing people to parse through daily onslaughts of rhetoric. The media needs to do the real homework on this topic, not simply represent one side. That tunnel vision is not going to help doctors ultimately, and more and more are beginning to realize it. There are plenty of links to primary and secondary sources in the above story and after it for those interested in learning more about this very complicated topic. And trying to understand this debate is important to every one of us, far beyond the interests of both doctors and lawyers.

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-11-20T15:50:59-06:00

- ID

- 77201

- Comment

- "I don't know the accuracy of his comments, and The Clarion-Ledger does not seem to factcheck its letters. So everyone should take that into account." That's right. The Doc is probably just lying through his teeth. Its all part of the conspiracy. Thank the good Lord that you are here to protect us against all of these bad people and bad groups and bad newspapers we suffer with here in Mississippi. When you talk down almost every single thing about Mississippi, you do it with such a smile on your face and such a light demeanor. Thanks. It really makes a difference when you soften the blow for us like that. And I really like that cape. :)

- Author

- VBell

- Date

- 2003-11-20T20:15:00-06:00

- ID

- 77202

- Comment

- VBell, did somebody steal your rock? Many newspapers don't fact check at all. They rely upon the integrity and reporting skills of their staff writers and freelancers. Hence the Steve Glass and Jayson Blair episodes. Even those that do fact check in general often don't fact check the Letters section. Most people who haven't worked at a newspaper or magazine don't know that. Many people assume that if it's in print, it must be true. Donna wasn't saying anything about conspiracies or intent to mislead. She was simply pointing out that often Letters sections aren't fact checked and therefore should be read with a reasonable degree of skepticism. Frankly everything should be read with a degree of skepticism, but that's another story.

- Author

- Nia

- Date

- 2003-11-20T21:27:07-06:00

- ID

- 77203

- Comment

- The impression I got from the letter was that the primary reason he didn't vote for Barbara Blackmon is that she (on behalf of her client through her law firm) is suing him. That seems an eminently reasonable justification for giving his vote to someone else. I'd say the rest might be considered smokescreen--except that he isn't reporting anything third-hand. These are real suits filed at his place of business. 30??? Would I vote for someone that sued me almost 30 times? Would any of you?

- Author

- Becky

- Date

- 2003-11-20T22:39:02-06:00

- ID

- 77204

- Comment

- Hey, that makes sense to me, Becky. I don't know anything about this particular case, so I can't address it without further research, which was my point. I'm certainly not accusing the doctor of lying; I don't know anything about him or his integrity, but that still doesn't mean that the letter is factchecked. Big difference in the journo world. That aside, though, he also made some vast claims in the letter that tried to characterize the malpractice problem overall, presumably based on some situations he was personally familiar with. His overall conclusions, though, do not match what research has shown overall for the state. So, it could be that he is facing a situation that is more unique to his practice. Again, I can't know without research, but neither can VBell in her rush to re-characterize my statements on this. Also, I mentioned the attribution issue because VBell copied almost the entire letter and copied (more than the "fair use" allotment that we can reproduce without permission) it here without saying what it was or who wrote it. To her credit, she gave the link. But as the Webgoddess (smile), it is my role to ensure that proper attribution is provided for materials posted here. Also VBell, if the JFP bends you so out of shape, simply look away, girlfriend, rather than let your anger get you all twisted up like a pretzel. Or, do some yoga. Besides, as you've pointed out, we only have a half-dozen readers, so what does it matter what we say? ;-)

- Author

- ladd

- Date

- 2003-11-21T02:38:45-06:00

- ID

- 77205

- Comment

- From MoveOn.org: "Statistics Don't Support Bush's Claim that Tort Reform will Minimize Costs" Arguing that his economic policies consist of more than tax cuts geared to the wealthy, President Bush maintained last week in his year-end press conference that tort reform is a key part of his "pro-growth" agenda, saying that it, "would have made a difference" to benefit the economy. Earlier this year, the president went further, saying that the proliferation of medical malpractice lawsuits are "a national problem that needs a national solution." But a recent study by the National Center for State Courts found that medical malpractice lawsuits per capita actually decreased in the most recent ten-year period examined. The president has tried to qualify his support for tort reform by insisting it's needed for plaintiffs with a "legitimate claim . . . [who] deserve a court that is uncluttered by frivolous and junk lawsuits." But the American Bar Association recently found that only a fraction of civil cases filed - 1.8 percent - went to trial. Fewer cases went to trial in 2002 than in 1962. While Bush claims, "everybody pays more for health care" due to "excessive litigation," a study released last month shows that medical malpractice insurers have raised rates on doctors well beyond the cost of payouts, particularly since 2001. Payouts and premiums for medical malpractice claims accounted for less than one percent of total health care costs. Even the president of the American Tort Reform Association said in 1999, "We wouldn't tell you or anyone that the reason to pass tort reform would be to reduce insurance rates." Medical malpractice costs as a proportion of national health care spending are less than 60 cents out of every $100 spent. In fact, malpractice premiums as a percentage of all health costs have declined from 0.95% in 1988 to 0.56% in 2000. On the other hand, prescription drugs costs make up about 11% of all health costs - the second largest portion after hospital spending - and are projected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to reach 14% in 2010. Despite these facts, the president chooses to support a Medicare bill that would prevent the Medicare administrator from negotiating lower prescription drug costs. List of sources included on the site.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2004-01-03T21:45:34-06:00

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus