Dust shimmers on the gray pickups and egg-crate-grille Chevrolets as tinsel and Christmas lights pierce the dark night. It is Dec. 22, 1969, and people are gathered on Main Street in Mendenhall looking up to the second floor of the jail, trying to see John Perkins through the bars on a second-floor window. They can hear children inside the jail.

"It's so dirty in here!"

"I'm going to smother up here!"

Eleven-year-old Georgia Ann Quinn is crying in the damp, dark jail, peering out the window to her older sister down below. But, like the other young people, she won't leave the cell without Perkins, her minister and mentor.

About 50 black people are on the street below, summoned by John's wife, Vera Mae, who told everyone she could find that they have Brother Perkins, Doug Huemmer and some children in the jail. The group had crossed the railroad tracks and marched up Main Street toward the jailhouse together.

Nearly all Mendenhall's black leaders are in the crowd, holding a vigil below the window. They are all looking up.

Perkins' oldest daughter, Joanie, 12, yells out: "Momma, they're beatin' up Daddy. And they broke Doug's glasses."

Almost 40 in 1969, John Perkins has blue eyes, thick glasses, a goatee and a slight stutter. He had come to the jail a few hours earlier to check on two local teenagers, Roy Berry and Garland Wilks.

Mendenhall police had picked Berry up and badly beat him for allegedly calling a white woman on the telephone. And they arrested Wilks for raising his voice to a white storeowner instead of surrendering to the obligatory, "Yassir."

Perkins is in the cell with 12 children, including four of his own, who are fresh from a Voice of Calvary Christmas pageant rehearsal, and Huemmer, a white volunteer from Glendale, Calif., who had plans to fly back home for Christmas that night. They all came with Perkins to the jail because he thought they all would be safe from arrest in numbers. He was wrong.

"Stand up!" Perkins yells to the crowd below.

Perkins tells his supporters to calm down and remember what they are after. He restates the demands of their community: better jobs, better living conditions, paved streets. Then, as he is speaking, the idea for a boycott comes to him.

"Don't buy one thing from the businesses on Main Street until they give us our basic human rights!" he shouts. He tells them they have to take a stand for themselves because the justice system isn't working. Right here. Right now.

Take to the Sky

Beyond the gates of the John M. Perkins Foundation at 1831 Robinson Road are open pink flowers and towering pear trees. The grounds contain the Perkins' former residence, the Antioch Guest House, an amphitheater, the offices, a playground, a community garden and a recording studio.

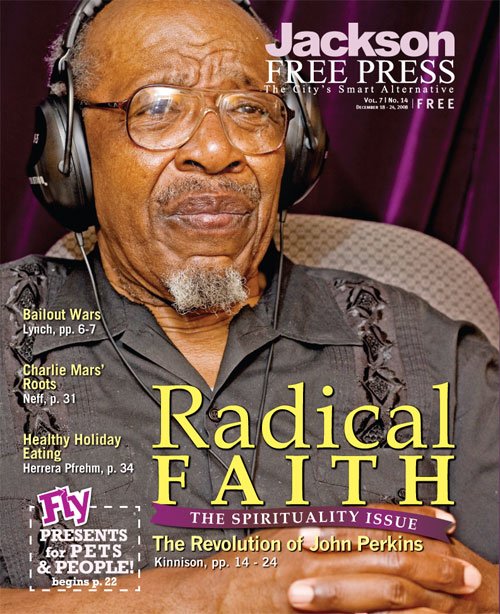

Now 78 with holes in his navy-blue polo and dust in his brown sandals, Perkins is rocking on the porch. The man known among evangelicals as the father of Christian Community Development smells like sweet olive oil and gardenias.

Perkins says he doesn't want to be like TV evangelists or leaders of large American churches who tell their congregants how to live. He doesn't want to be a cult leader. "I don't look at those followers of those preachers as very intelligent. I don't want too many people to believe in the way I act," says the evangelical with many liberal political and social views.

A third-grade dropout from Greenwood Elementarythe all-black school that served eight grades near his home in New HebronPerkins learned to read through what he calls the "collective classroom" and through his Uncle Bill's subscription to the Jackson Daily News throughout World War II. He liked "Sky King," with its "helicopters and monorails of the future."

Perkins shared a three-room shack on the plantation of Mr. Fred Bush with his grandmother, Babe Perkins, his five siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles. His mother, Maggie Perkins, had pellagra, a protein deficiency that was supposed to be extinct in the United States by the time he was born in 1930.

Maggie died when Perkins was 7 months old.

His father, Jap Perkins, visited him once when Perkins was 4 years old. He stayed for one night, and the next day Perkins followed him all the way to the train. "Naturally, we would both go," he thought then.

But Jap lived with a woman in the Delta who didn't want his kids around. Jap and Perkins walked a few hundred yards, and Jap turned and hit him with a switch telling him to go back home. He hit him with the switch again and again until one of Perkins' aunts came and took the boy back home.

Growing up, Perkinsthen called "Toopy"had to fend for himself. When he was 12 years old, he and a friend took a day's work hauling hay for a white plantation owner. He thought he would make a dollar and a half or two dollars.

"At the end of the day, he gave me 15 cents! I could hardly believe it. Fifteen cents!" Perkins says.

He didn't know whether to take the money or not. "I was afraid. Afraid if I accepted the money, I would hate myself for taking it. Afraid, too, if I didn't take the money, the man would say I was an "uppity, bigot n*gger" or maybe a "smart n*gger."

He took the money. "I took a long look at what had just happened to me and really began thinking about economics. That man had the capital: the land and the hay. He had the means of production: the wagon and the horses. All I had were my wants and my needsand my labor. So I was exploited," Perkins says.

Perkins looked up to his brother, Clyde. His grandmother couldn't afford to raise them all and had to give away his other five siblings, but she kept him because he was the baby and kept Clyde because he was old enough to work in the fields.

His family was known for their bootlegging, gambling and overall toughness. "The Perkinses just wouldn't take nothing off of nobody," Vera Mae says.

At that time, the white leaders sent away "tough" black boys like Clyde to World War II. Clyde returned with a Purple Heart, several combat awards and an honorable discharge. He was no longer "accustomed to his place," though. War changed his view of selfhood. And 16-year-old Perkins noticed the difference in his brother.

One Saturday evening in summer 1946, Clyde grabbed the Mendenhall deputy marshal's club as it went to strike him from behind for a second time. The marshal stepped back and shot Clyde twice in the stomach. He died later that night.

"I saw the blue coffin lying open on the red earth," Perkins says. He knew if he didn't free himself from the cycle, he says, "I would have just adjusted myself to an inferior life. I wouldn't have to do anything but just exist."

"I think everyone is born with a little intelligence, but I think society dumbs them down ... When I was a child, when I was working in the field, I talked to myself. I talked out loud. Always talking, thinking, trying to understand," Perkins says now. "George Washington Carver did that. He talked out loud to his plants. And they talked back to him. He learned what was inside the plants and turned it into productivity."

In 1947, the same year electricity came into his family's home, his family sent Perkins to California to find prosperity, and to avoid the fate that befell his brother.

The Economics of Faith

Raised in that tough family in New Hebron, Perkins had no concept of God or religion. He thought black churches with their wailing and waving were just a people blindly following others. He thought the Bible was full of superstition and old wives' tales. He served the church of money and success.

In California he found hope, and money, before he found God. There he made 98 cents an hourthe same as white workersat the Union Pacific Foundry in South Gate as part of a crew that made cast-iron pipes for sewage and plumbing. It was a major step up from the $20 dollars per month a black man could expect in Mississippi.

"I could see glimpses of hope that were once blocked off to me," Perkins says of his life in California.

After some time in the coastal town, he helped his crew devise a new production line setup that improved efficiency. "Under the old system, each crew would produce between 90 and 100 pipes a shift. But under the new system, production went up into the thousands," he says.

As production increased, their wages stayed the same. Perkins led a strike that succeeded in bringing new wages and benefits to the Foundry's workers. "Even years later, with some of the other things I managed to do, I still look back to that event as my claim to fame: pulling that strike together. I never forgot the potency of united action," Perkins says.

By then, though, Perkins wanted more than paychecks. He yearned for a faith that is internal rather than external.

In 1949, Perkins talked with Vera Mae Buckley outside Pleasant Hill Baptist Church during a visit to New Hebron. "I knew I had met the girl I was going to marry," he says.

Perkins went back to California. He and Vera Mae wrote letters and made plans. In 1951, Perkins was drafted into the Korean War. After basic training, they had a whirlwind wedding and honeymoon.

While in Korea, Perkins read everything he could get his hands on. He learned about communism, economics and anything he thought would quench his thirst for faith. Perkins got out of the Army in January 1953. Vera Mae moved to Monrovia, Calif., that same year.

Their first son, Spencer, was born in 1954. As Spencer got older, he pestered Perkins to go with him to Bible class. Perkins went with Spencer and, over time, started to entertain the idea of God existing for a black man.

Perkins began studying with Jack MacArthur of Calvary Baptist Church in Burbank, Calif., and J. Vernon McGee, a Presbyterian minister in Pasadena.

By 1958, Perkins was on his way to becoming a well-known Christian leader in Pasadena. He was an ordained Baptist minister and conducted Bible studies with people in his community. He befriended not only black Christians but white evangelicals. He even preached at some white churches.

In 1960, Perkins knew God wanted him to return to Mississippi. Neither he nor Vera Mae wanted to come back. Their by-then five children were happy in California. But, that summer, they returned to Simpson County to start a ministry.

The following year, they bought a large tent in which they held meetings in towns around Simpson County. "Not usual 'tent meetings' with flashy singers and a big production and all. No way," Perkins says.

Perkins returned to Mississippi on a platform of youth evangelism. He wanted to teach young people about Christianity, help them go away to a Bible college and then return to the community as leaders.

Digging Ditches, Building Hope

Dolphus Weary, now the director of Mission Mississippi, was standing in the crowd below Perkins' window in Mendenhall that night in 1969. Then 23, Weary was the first young person to complete John Perkins' youth program.

"The scary thing about it was if they could lock up our leader, our hero, then what did that mean for any of the rest of us? Could they just decide to do anything they want to any of the rest of us?" Weary says, sitting in his office in the Plaza Building in downtown Jackson.

Weary grew up in D'Lo, Miss. He attended Harper High School, which also served as a junior high and elementary school along with about 500 to 600 black students.

Weary, then 17, met Perkins in Mendenhall in 1964 when his friend Leonard Stapleton took him to a tent meeting led by Perkins and Vera Mae. He was surprised to find a preacher who lived in the community. In the early 1960s, the black church in Mississippi was still a place where people met to hear a preacher from 50 to 100 miles away and leave an offering, not an institution that reached out into the community, Weary says.

The black community had little infrastructure. When it rained, the streets were perilous and filled with potholes. When it was hot, the dust settled over everything.

"He (Perkins) was sick of our people living in dust," says Artis Fletcher, another teenager Perkins groomed into leadership. Fletcher is now the pastor at Mendenhall Ministriesthe ministry that Perkins and his family started in 1960.

Preaching self-empowerment and community redevelopment did not mesh with the way black churches had always done things, though. Perkins was not well received.

"It was two-fold: One, it had to do with his message was a message of community development. So in some ways the black church rebelled against his message, and the white community wouldn't hear his message at all," Weary says.

Like Perkins, Weary had grown up working in the cotton fields and constantly doubting his self-worth like Perkins. "If hopelessness was driving me out of Mississippi, hatred had driven John out," he says.

Weary learned that one of the things Perkins did as a new Christian was visit California prison camps in the San Bernardino Mountains. The boys in the camps were only 13 to 17 years old, stationed there to help contain fire outbreaks in the mountains. When Perkins saw these young men, he knew the problem had to be dealt with at its source: Mississippi.

"I respected him for that choice," Weary says. "It wasn't the one I would have made. Here was a guy who had it made in California. He had a good job and was moving up in his company. He'd just bought a 13-room house. But he had such a desire to see things change, to make a difference."

Weary took a trip back to California from Mississippi in summer 1964 with Perkins, Vera Mae and their then-eight children in the summer after his junior year of high school. There, he discovered a new way of life, full of possibility. He met the people who had helped transform Perkins' hatred into a passion for Christ, selfhood and community.

"When I got to California and saw orange orchards and the ocean and all, it was like an impossible dream come true. I just wondered, 'What am I doing out here?'" Weary says.

By 1965, Weary was a high school senior and knew he wanted to get out of Mississippi. But he didn't know how.

Basketball became his ticket out. He tried to play at Mississippi Valley State College, but failed to earn enough to pay tuition. He got a basketball scholarship to the Prentiss Institute, but his loans were choking him. Finally, he got an appointment with the coach at Piney Woods Junior College in Piney Woods, Miss. He promised Weary a basketball scholarship. Blindly, Weary dropped out of the Prentiss Institute and arrived at Piney Woods only to discover he had never been registered.

Down and broke, Weary took a job laying sewage pipe in Anguilla, Miss. He recalls his time digging ditches as a period when he felt ashamed of his poverty and of not being able to break out of the black man's cycle. He had to do something, so he went back to Piney Woods to try for another spot for the January semester. He got in and claimed his scholarship.

As things started to go better for Weary, he began to feel a tug toward ministry. His role model was still John Perkins.

Voice of Calvary

By 1962, Perkins' ministry in Mendenhall was expanding. Perkins farmed in the mornings and performed Bible studies at schools in Simpson County and surrounding counties in the afternoons. That year, he took his savings of $900 and bought five lots on the outer edge of the black part of Mendenhall.

Weary, his brother Melvin Weary, Artis Fletcher, Leonard Stapleton and several other boys from the ministry helped build the shell of a large house for Perkins and his family to live in on one of the lots.

In 1963, Perkins went back to California to ask his friends for money to continue his ministry in Mendenhall. Calvary Baptist Church in Burbank had a particular interest in rural ministries and came through. Perkins would act as a rural ministry spokesman for Calvary Baptist for the next seven years.

Perkins returned to Mendenhall with $6,000part donation from Calvary Baptist Church and other churches and part proceeds from the sale of his California home. With this money, Perkins developed Berean Bible Church, Glenna Bell Hall School and acquired a school bus. To honor his new sponsorship, Perkins called his ministry "Voice of Calvary."

"I liked the way that John was interested in living among us in the neighborhood," Weary says. "It was another way he was different than other preachers."

During Weary's second year at Piney Woods, Perkins introduced him to David Nicholas, the director of admission at Los Angeles Baptist College and Seminary. Nicholas invited Weary to attend.

Weary was plagued by old feelings of inferiority. He remembered how dirt would crumble from his boss' boots up on the bank and fall onto his back while he dug down in the ditches. He feared he couldn't make it outside Mississippi academically or even as a basketball player.

Finally, Weary went. He and his friend from Piney Woods, Jimmie Walker, became the first full-time black students at the Los Angeles Baptist College. From there, Weary went onto Los Angeles Seminary, to coach the LABC freshman basketball team, and to play basketball for the Crusaders, a team sponsored by the mission group Overseas Crusades, on a six-week tour of the Far East.

But, like his mentor, Weary was needed back in Mississippi.

Weary came home to Simpson County each summer while he was in school at LABC. The first summer, he tried to get a job comparable to his education, but there were only cotton fields, cornfields and service jobs available to black men.

So he and Perkins sat down and came up with a vacation Bible school for young black boys that focused on leadership and self-empowerment. Weary traveled to several churches a day giving Bible studies each summer. The focus of the group meetings was empowerment through faith and pride in one's self.

Continuing that theme, the decrepit school bus Perkins used to bring adult men to his Fishermen's Institute for Bible school began taking blacks to the voting polls. In 1967, there were 50 registered black voters in Simpson County. Perkins and his crew traveled around educating people about voting rights and standing with them when they went to register. They helped register 2,300 blacks to vote.

"Some of the churches in California that had been supporting John Perkins saw a dichotomy between social justice and evangelism: Either John was preaching civil rights, or he was preaching the gospel," Weary says. "Somehow they couldn't see that these were not opposites. It was not either/or, but both/and."

Perkins could no longer preach his "whole gospelԗwhich included the need and will to seek education, health care and better wageswithout becoming involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

"One of the greatest tragedies of the Civil Rights Movement is that evangelicals surrendered their leadership by default to those with either a bankrupt theology or no theology at all, simply because the vast majority of Bible-believing Christians ignored a great and crucial opportunity in history for genuine ethical action," Perkins says.

Perkins found himself between evangelical Christians and civil rights workers. He was neither. He was both.

The social changes Perkins, Weary and friends were making in the black community cultivated a group of like-minded people with the manpower for the boycott he urged that night in the Mendenhall jail.

Vera Mae got the boycott rolling by daybreak while her husband and Doug Huemmer sat in jail. She convinced blacks to go shop in Magee or Jackson instead of Mendenhall. Young blacks started picketing the businesses. African Americans with signs on the street corners kept most white shoppers away, too.

The petition, "Demands of the Black Community," began: "The selective buying campaign in Mendenhall, Simpson Co., was launched today, Dec. 23, 1969, primarily to secure employment in the business establishments in our town." Blacks were 30 percent of Mendenhall's consumer base, according to 1967 Simpson County records.

The deputies removed the children from the cell by force on the night they were arrested. But Huemmer and Perkins waited to make bail the evening of the last shopping day before Christmas to make white shop owners sweat and allow the boycott to have maximum effect. "Christmas Day, everybody tried to pretend it was like other Christmases. But we knew a new road had been taken," Perkins says.

The boycott continued through January and February after Perkins' release and began to draw blacks from all over the state to picket on Saturdays. Each Saturday they walked the streets of Mendenhall chanting, "Do right, white man, do right."

Perkins had no idea the boycott would propel him into a larger spotlight. He inspired blacks with the idea of "green power," as Perkins calls economic power, but he also inspired whites who didn't like "smart n*ggers" to take action.

Jail As Classroom

"I'm Grandpa Perkins. You are my grandkid, I'll be your grandpa," he says while handing out Bibles to a room of 16 black boys at the Hinds County Jail on July 19, 2008. "It's great to see you all. Not good to see you here but good to see you as a human being."

The kids respond with "Yes, Sir." If this were an audio scene, one might think he is speaking to a prep school. But their hands and forearms are full of home-scratched tattoos, and they are wearing brown and yellow jumpsuits, white socks and plastic, tan sandals.

Perkins takes his hat off. The boys begin playing with it, trying it on and reading the ministry's logo on it. An inmate named David, 17, sits in the front row, tapping his left foot.

Grandpa Perkins slams his hand down on the table. "You're going to get out of here. ... I was 7 months old when my mother died. Now, I get $2,000 a lecture. People pay to hear me speak. This ain't the end. I've been in jail, too," he says.

"Open your Bibles to Matthew, Chapter 4."

Their teacher Mrs. Holmes, a small white woman dressed in frilly floral complete with shoes with flower appliqués, sits in the corner nodding after Perkins' proclamations.

"There's no person in this room more important than you," Perkins says under signs that read, "The Motivation Formula" and "The 'Reality' Ride."

"I feel it's my honor to be here with you guys," Perkins says. "Anybody want to read?" Before he could finish asking, hands went up.

"That's beautiful. That's beautiful reading, guys," he says afterward.

He begins to lose them. The boys in the back start laughing among themselves.

"Y'all want to be successful?" Perkins asks. They answer with a resounding "Yes." He says that he paid for his new house with $159,000 in cashier's checks.

"Can you bond me out?" one of the boys squawks at him.

"My mother died of starvation," his elder answers without missing a beat.

Perkins tells the boys he has traveled the world. They can do it, too, he says. He didn't finish third grade, but now he has eight honorary doctorates. They can do it, too.

Grandpa Perkins sounds like a politician rallying his constituency. He gets louder with each example. And even the boys in the back discussing their new ideas for tattoos look up from their arms and listen. "You can fool some of the people some of the time. But you can't fool all of the people all the time," he warns.

David has one tattoo on his left hand that says "Jack" and another on his right hand that says "Town." He is attentive. He sits up in his seat, rocking back and forth, nodding and saying "Amen." He's been in for one month. The boys in this room committed felonies. "They didn't do no little thing. They did something serious," Perkins tells me.

"Boy, demons can get into you." He stops and looks around. He says it louder this time: "Demons can get into you. But Jesus can cast them out. You've all done crazy stuff. It was crazy, wasn't it? You know it was crazy." The boys laugh, nod, and a couple are weepy-eyed.

David tells me afterward: "I've never met him before. But I understand what he's saying. I want what he's saying."

One in three black boys will go to jail, the Children's Defense Fund reports.

The Vision and the Prophet

"His concepts, his principles about community make sense," Eric Stringfellow says.

"The key is to have people with the wherewithal to live anywhere, who choose to live there. There are complex issues when you live there. Look at Jackson: I don't think we have a level of sophistication among our leaders to really address the problem."

Stringfellow is the director of Tougaloo College's mass communications department and the former public editor of The Clarion-Ledger, where he still writes a weekly column.

"It's more than just a church thing; it's a social action thing. Before John, I was taught to keep church at church," Stringfellow says.

In 1971, the Perkinses lived up the street from Stringfellow and his five siblings. He joined Perkins' Good News Club, a sort of vacation Bible school, when he was age 12.

"We were neighbors," Stringfellow says, leaning back in his chair wearing a stark blue pullover, khakis and sleek glasses. "He's probably shaped my life more than anyone else. He's in the top three. It's my father, my grandfather and Reverend Perkins."

The Perkins family moved from Mendenhall to Jackson in 1971. Threats on their lives from the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists in the area drove them out.

They prayed about the move to Jackson for years before finally leaving Mendenhall. And, at first, they commuted the 90 miles everyday. In 1973, they bought a small house on St. Charles Street, in West Jackson. The neighborhood continued to decline.

Around the same time, Weary, then 27, came home from California with the hope of working with Perkins in Mendenhall. But, with Perkins living in Jackson, Weary took over the Mendenhall ministry. Within a few years, Weary had facilitated the development of a black-owned construction company, a housing co-op, a counseling center, an economic development program, legal services and an expanding health center. All these structures are still in Mendenhall today on the same plot of land Perkins bought in 1962.

When asked if Perkins ever pushed him too far with his strong personality, Stringfellow responds, laughing, "Good question. Good instincts." He says he stood up to Perkins. "John is strong-willed, but he wants to be challenged," Stringfellow says. "I've always found him that way. If you challenge him, if you stand up to him, he respects that."

Perkins is a bull who plows in headfirst, and Weary is a gentle man with a clerical collar, an office in a tower and a luxurious voice. "He (Perkins) will tell you today, 'I can go into a place and make people mad and Dolphus can go behind me and smooth people over,Ҕ Weary says. "I'm a bridge builder; he's a prophet. He has a prophetic message. That prophetic message needs to be heard, but prophetic messages make people uncomfortable."

Weary says that it was only five years ago that he found the courage to stand up to his "spiritual father." Weary was driving Perkins to Yazoo City and wanted to tell him about a solution to a problem he had.

Perkins, of course, started giving advice. Weary said, "Shut up!" Weary told Perkins that he didn't want his opinion; he just wanted him to listen. That's the day Perkins says Weary grew up. Weary was 58 years old.

While the strong-willed Perkins was trying to get a new Voice of Calvary off the ground in the 1970s, the white church was going to Chicago and Phoenix to work with Native Americans and Africa to work with Africans, while not doing very much to help the needy in their own backyard, Weary says.

"John was a completely different sort of minister. His faith made a difference," Weary says. "It went beyond emotionalism. It was a faith attached to reality. He tied it to voting, to politics, to poverty, to the here and now. That made him very attractive to black folks in Simpson County."

It's always been difficult to classify Perkins. "He is full of unexpected surprises," says Charles Marsh, director of the Institute of Lived Theology at the University of Virginia who wrote about Perkins in his 2006 book, "Beloved Community."

"He is also a moral conservative. He's pro-life. He admires much about the blunt power agenda. When you try to fit that into a neat mold, you can't. And that's what makes him so interesting to me," Marsh continues. "But also what makes him perhaps a bit difficult to recognize at the local level."

Perkinswho is today known nationally more than inside his home statewas willing to go outside Mississippi to raise money for his ministry here. "California was the first pipeline, and then he went to Colorado and Seattle, Wash. So when I came to the ministry, I started traveling in a network of about 12 cities," Weary says.

The primary funding came from large white churches outside the South like Calvary Baptist Church in Burbank, Calif. Out-of-state churches began to put Perkins' ministries in their budgets and send volunteers to work in Mississippi. The volunteers took the message home with them, Weary says, even as far fewer volunteers came from within Mississippi.

Voice of Calvary still had to deal with racism and segregation. "In Lawndale (a ministry in Chicago), you had a white guy coming from Wheaton College into a black community. And he paid his dues," Weary says. "But you could draw a circle around Chicago and find all the resources you need."

The "white guy" who started Lawndale ministries is Wayne "Coach" Gordon. He had already relocated to the black community of Lawndale on the south side of Chicago and was working as a teacher and coach when he read Perkins' autobiography "Let Justice Roll Down" in 1976. Gordon was living out the tenets of Perkins' community development theoriesthe three R's: relocation, redistribution and reconciliationbefore he read Perkins' book or had met Perkins.

Relocation means living among the people you are trying to help. "It's about making friends," Perkins says. Redistribution means bringing education, talent and resources back to poor neighborhoods but also working to rectify the social and political structures that created the "need" in the first place. And reconciliation, in its simplest definition, means reconciling Christians as one body of Christ.

After reading his book, Gordon took Perkins as a mentor and asked him to be on the advisory board of Lawndale. The ministry has grown in 33 years into a framework of community development that includes the Lawndale Christian Health Center that now serves more than 75,000 patients and the Lawndale Christian Development Corp. which provides housing, educational enrichment and community advocacy.

During the 1970s and '80s, Perkins became popular on the national evangelical stage, appearing at Billy Graham crusades, political prayer breakfasts and at the Urbana Youth Leadership conferences. Carl F. H. Henry, Frank Gabelein, Charles Colson, Tony Campolo and Doug Coes befriended him.

"He appeared at Christian colleges and seminaries, lectured to student organizations from Harvard to Howard, and was invited onto the boards of evangelical and human rights organizations, including Bread for the World, the National Black Evangelical Association, and Koinonia Partners. He became a Ford Foundation Fellow and a consultant to Democratic and Republican presidential candidates," Marsh says.

But even as hundreds of evangelicals and social-rights workers were coming to West Jackson from all over the nation to stay at Voice of Calvary, learn the Christian Community Development model and take it back to their own communities, Jackson's churches and social groups were still uncomfortable with Perkins-style ministry.

"There was a little bit of rebellion in terms of how he (Perkins) was received by black leaders in Simpson County and some of that spread over to Jackson as well. It was about a comfortable system that wasn't working for the greater good of the community," Weary says.

In 1982, Perkins moved back to Pasadena where he and Vera Mae started the Harambee Christian Ministries that, like his other ministries, focuses on the needs and individual faith of the urban poorespecially mothers and children. In February 1983, Perkins and Vera Mae started the John M. Perkins Foundation for Reconciliation & Development. Its mission was to spread their Christian community-development ideas around the world.

Christian organizations, modeled after Perkins' ideals, began springing up all over the nation. In 1989, Wayne Gordon and Perkins decided to bring these groups together under he Christian Community Development Association. Gordon was the founding president of CCDA, and Perkins the founding chairman. Gordon says he and Perkins have been to more 100 cities together to speak. The CCDA meets annually and has 8,000 individual members and 500 member organizations.

Perkins returned to Jackson in 1996 to retire, according to Fletcher, who was the first boy to ride around with Perkins from morning to night in the mid-'60s.

Weary says that he personally wanted to see Perkins take local leaders like himself and propel them into a broader recognition using his national network when he came back to Jackson the last time. "Mentor us. Get us out there," he says.

But after the sudden death of Perkins' son, Spencer, of heart failure in 1998, Perkins dedicated himself to Spencer's work at the John Perkins Foundation in West Jackson. The foundation renovates and rents houses in West Jackson primarily to single mothers and their children through their Zachariah 8 program. They host interns from all over the nation. The Antioch House serves as a meeting place and hotel for out-of-town Christian leaders and a facility for their after-school program.

Perkins' latest project is the Retreat Center. He and Vera Mae moved across the parking lot from their old house into a large structure on Robinson Road. Starting in January, he will begin hosting retreats for pastors, educators, and community and ministry leaders there. It is part of his plan to continue his work while staying closer to home.

The Spencer Perkins Foundation, on the John M. Perkins grounds, hosts facilities including a playground, three basketball courts, two classroom buildings, pavilion, amphitheater and baseball field. They have an Afterschool Program, Summer Arts Camp, Girls and Boys Club, and Good News Clubs at different times during the year.

Community workers from all over the nation come in every year to learn from Perkins and volunteer to build houses and working with children in the community. Westmont College, in California, sends 20 to 30 students each summer to volunteer at the Perkins Foundation. Andrew Koch's best friend attended one of these trips in 2005 and went home to Santa Barbara raving to Koch about his experience in Jackson.

Success, Redefined

Koch, 23 and white, is Perkins' assistant and office manager. He met Perkins at Westmont in fall 2006. "I just needed something meaningful. I grew up in Minneapolis constantly confronted with the problems of the city."

Perkins' story and message wasn't new to him. Perkins was involved with the church he grew up attending in Minneapolis. "But it struck a new chord with me after the enlightenment of college," he says, allowing the word "enlightenment" to take on a slightly exalted tone, mocking himself.

"Oh, you're a writer," Perkins said. "Come down and work on my memoir." Koch recalls: "I thought that's insanity. I can't just pick up and do that."

Koch says he wanted to make sure Perkins didn't turn out to be crazy. "I wanted to make sure he wasn't another Jeremiah Wright," he says. He discovered that Perkins' story was not only true but also meaningful. "And I guess he is a little crazy," he says, laughing.

Perkins did not give up. In late August 2007, Perkins called Koch and said, "Come on, we have a position for you."

Koch says he knew so many men in their late 20s who went to the beach everyday, drank and worked in a restaurant. He says that he was afraid that if he didn't take Perkins' offer, he would wake up in six or seven years and realize he had wasted years of his life. So he moved to Jackson.

"I'm enjoying ministry right now," he says.

Koch, who calls his boss "JP," is blunt about both the work of Perkins and about Shane Claiborne, a young, white Christian community leader in Philadelphia, Pa., who has created a modern, cooperative community. "I think both Claiborne's message and JP's message can be alienating. JP advocates relocation. Not everyone can come back. How can they help from where they are? And with Shane Claibornenot all of us are granola-eating hippies who can live the way he lives. How can ordinary people help?"

"I think there is a real longing for it," Koch says of social action. "I get to travel to schools with JP every few months. Everywhere we go, we run into young people like us who have a thirst for change. ... We see people who have a radical desire to see God at work in people's lives." Koch says that Christian Community Development is not just a personal religion but a religion that can permeate through the community creating radical systemic change.

Weary says Koch and others like him are the current generation of Dolphus Wearys and Artis Fletchers. "(Perkins is) taking the work in West Jackson and building on it," he says.

Elizabeth Perkins, the youngest of Perkins' eight children, is the executive director of the John M. Perkins Foundation. Irma Driver is the president of Voice of Calvary Ministries, and Ernestine Skiffer is the president of Mendenhall Ministries. Skiffer says that women coming on the scene may be the new movement. The black men had to struggle to be taken seriously and make headway as leaders. Now, these women are opening doors in the same way Weary had to and Perkins before him.

Two other women, Alexis Spencer-Byers and Lee Harper, started Koinonia Coffeehouse at 136 S. Adams St. in West Jackson. Koinoniaa New Testament word for fellowship and the name of an "intentional" multiracial Christian farming community in Georgia in the 1940sopened in June right off the Jackson State parkway. Harper, a striking, black woman with dreads, says they are not directly affiliated with Voice of Calvary Ministries. "But we get a lot of prayers from over there," says Harper, smiling, brewing coffee behind the counter on a cold December morning. "It's hard to say we're not kin."

Harper and Spencer-Byers attend Voice of Calvary church. Harper was president of Voice of Calvary for three years.

Spencer-Byers, a petite white woman from Massachusetts, moved to Jackson for an editorial internship with Urban Family Magazine, which was run by Perkins' late son, Spencer, and published by Perkins. And in the last 10 years she has worked for both Voice of Calvary Ministries and Mission Mississippi.

"My husband grew up in John Perkins' ministry. He has been a part of the ministry since Mendenhall," Harper says. She and her husband, Larry, live above Koinonia.

Harper and her family live by the three Rs, spending more than 20 years in the West Jackson community living by the tenants of relocation, redistribution and reconciliation, she says.

"You have to sacrifice," she says. "I was a business major, and they teach you that a big part of a business plan is the location. ... This is the right location for us and what we want to accomplish. This is our community," she says.

Harper says she is not in this to make money.

"We are out to contribute to the economic development of the community. All vibrant and thriving communities that are nurturing and productive have economic development," she says. "Without economic development, we will never get rid of the blight. We are not going to have the kind of success that most people recognize as success," she says.

'This Is So Wrong'

It has never been the exact time or season for Perkins in Mississippi. In 1960s Mendenhall, not even the black churches would listen. In 1970, he began to travel for resources to send home. He left in the '80s for California and didn't return until 1998. It wasn't until the late '80s that speaking opportunities for a black evangelical Christian man began to open up.

"The problem with a visionary is that he can't stay around his own vision too long, or he'll mess it up because he goes from one vision to the next," Weary says. "He and I used to argue about him wanting to start something else when we hadn't worked out the last thing."

The success of Mendenhall is that Weary came back and developed it. The success of Voice of Calvary is that various presidents stayed and developed it. The success of the Perkins Center depends on how well Perkins' daughter, Elizabeth Perkins, is able to take hold of it and how much Perkins is willing to let go of it, Weary says. "That's been the challenge of a visionary prophetletting go. And it's not bad; it is just the reality."

In 1994, Marsh attended the 30th anniversary of Freedom Summer. One of the sessions focused on who continues to live in Mississippi to carry out the unfinished business of the Civil Rights Movement. "And there were names flashed on the screen. No mention at all of John and Vera Mae Perkins. And I just thought, as my students would say, 'this is so wrong,Ҕ he says, drawing out the last word like a teenager.

Perkins' followers believe he hasn't stayed put in Jackson for any period long enough to keep local generations aware of him. "I've lived my life by the dozens. I lived in each place for around 12 years and then changed," Perkins says.

"For me, I had never heard his story until a couple years ago. And then I began to hold him in high regard. It may just be a lack of information," says Stan Buckley, pastor of First Baptist Jackson, the largest Baptist church in Mississippi.

Buckley doesn't think Perkins' relative obscurity in the city and state are due to his race: "As far as being open to him, for example, Dolphus (Weary) speaks at our church. As far as somebody (a black man) speaking, that is really not an issue these days."

"I think his gifts are better utilized on a national level," says Koch, whom Perkins called to ask whether he should wear the black shirt when having his picture taken for this article. "Yeah, the black shirt is good," Koch says, like a proud papa.

"A prophet is without honor in his own town" is the line Weary, Stringfellow, Marsh, Koch, Elizabeth Perkins, Artis Fletcher, and Gordon all quoted in regard to the paucity of knowledge about Perkins in Jackson. The exact verse is Mark 6:4: "There is no Prophet without honor except in his own country, and among his own relatives, and in his own home."

"I think being a Christian social visionary is work that really can't be measured by the normal standard of success or failure. I think the success is the kind of vision that was born in his five decades of struggle, his five decades of commitment to the poor," Marsh says.

"Look, in 1964, thousands of organizers came to Mississippi. It was cool. It was sexy. This was hip activism. They all left. They all went on to other things. The Perkinses never left. I mean they spent some time in poor neighborhoods in Pasadena. But they have been walking the walk. I think that's the story of how you stay; you keep your hands to the plow. How you keep doing the work long after it has stopped being cool or sexy. That's not about success or failure; that's about perseverance."

"I regard John Perkins as the most influential African American Christian leader since Dr. King," Marsh adds.

There Was No Fear

On Saturday, Feb. 7, 1970, John Perkins, Rev. Curry Brown and Joe Paul Buckley were arrested when they tried to get Huemmer and some Tougaloo students out of the Brandon jail. Authorities had picked them up on a reckless-driving charge in Plain, Miss., while they were trying to return to Jackson from one of the boycott marches.

Rankin County Sheriff Jonathan Edwards, his son Jonathan Edwards Jr. and deputies beat them badly. They beat Perkins unconscious. They shaved Brown's and Huemmer's heads. They poured moonshine on their scalps and in their wounds.

They stuck a fork with two middle prongs bent down up Perkins' nose and down his throat. "When I came to, I heard them ordering Rev. Perkins to mop up the blood on the floor," Huemmer testified in the trial. "Rev. Perkins was lying sorta stunned on the floor, and they kicked him until he got up."

They made Perkins mop up his own blood because word came that the FBI was coming. The FBI never came.

Through the night, the deputies made Perkins read the demands of the black community of Mendenhall while blood gushed from his head and his throat swelled from the fork.

Huemmer and the Tougaloo students testified that they were sure Perkins would die that night. He didn't. Alfoncia Hill, a lady from the community, signed over her property and bailed Perkins out the next afternoon.

Perkins still suffers physical pain from the beating. Two-thirds of his stomach had to be removed because of it. He suffered a mild heart attack shortly after the beating. The pain was constant. He began to overlook it. He learned to keep going.

While recuperating at Mount Sinai Hospital in the all-black town of Mound Bayou, he confronted his hatred of whites. He decided he couldn't live and hate. So he let it go. If he were reading this, he would say, "It ain't that simple."

But, now according to his friend Lowell Noble, who lives at the John M. Perkins Foundation with Perkins nine months out of the year, Perkins' one regret is that he did not focus more of his ministry on poor whites in the community. "Isn't that amazing? He really means it," he says.

In July of this year, Perkins went into Baptist Hospital because he was having intestinal problems caused by the stomach issues that have plagued him since the beating. "I thought more about dying when I was in the hospital this time," he says. "... I thought of it in reality. It was a part of the sickness and meditation, pain and so forth. There was no fear."

"That's a process in major revolutionary leadership where you live beyond death. .... You think about that your death is going to be more important than your livin'," he says. "I think that's when you become an effective people, society changer. (You) recognize death is a reality and what you are doing has death in it. And I think you move beyond that."

"Did you get any sense of who I am?" Perkins asks during one of our last interviews. He smiles, pulling at his black button-up shirt around his scar that starts from below his belt and continues, all puffy patchwork, to the top of his stomach.

"I talk to the out-of-the-way people. That's what I do. That's my life, taking these thoughts down in books," he says.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 142390

- Comment

Thank you. His story cannot be told enough.

- Author

- lanier77

- Date

- 2008-12-18T09:45:18-06:00

Comments