A half moon disappeared as the sun rose out of the Atlantic Ocean on Sept. 1, 1832. The humid coastal winds filled the sails and carried the ship through the waves as J.W. Martin captained the Schooner Wild Cat, a 40-plus ton sailboat, out of the port of Charleston, S.C.

The ship headed south out of the port, just beyond the coast of white-sand beaches, bordered by a thick forest of oaks and palms.

Among the tons of cargo, six pieces were unique. By law, Martin had to fill out a manifest of these six possessions and present it to the collector or surveyor of the port when the ship arrived at its destination—New Orleans—in a little more than three weeks. On the pre-printed, fill-in-the-blank manifest, he recorded the owner of the cargo and where the owner lived. He also recorded the basic information of the cargo by name, sex, age, height and color.

Willis — male, 20, 5 feet-8 inches, black.

Jack — male, 25, 6 feet, black.

Hector — male, 20, 6 feet, black

Adam — male, 20, 5 feet-8 inches, black.

Maria — female, 19, 5 feet-4 inches, black.

Mary — female, 7, 3 feet-6 inches, mulatto.

On board, these six young people knew they would probably never see their families again. They were headed to their new home and their new owner. They would spend 23 days on the Schooner Wild Cat before they reached the Gulf Coast's largest port.

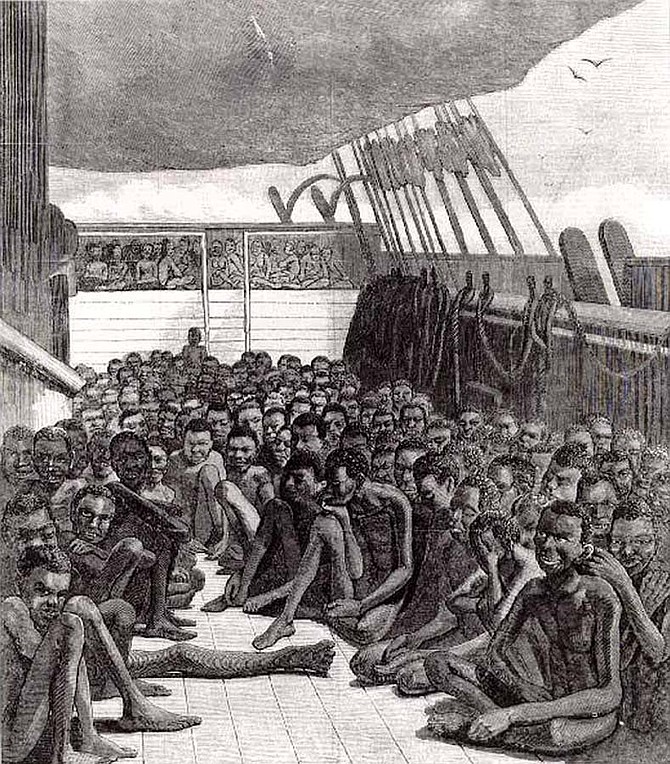

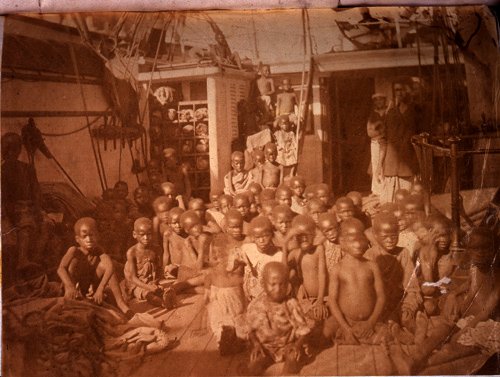

These six passengers likely spent the trip with chains on their wrists, ankles and even their necks. They suffered hot, cramped, shadeless conditions above deck, and even more crowded and damp confinement below. Dysentery and seasickness were common on such trade vessels.

Once they arrived in New Orleans, the collector of the port would check the six young slaves against the information on the captain's manifest. If they matched the description given, the collector would sign the manifest and give the slaves over to or ship them to their new owner.

In 1832, these six people were likely going to spend the next 30 years working a cotton farm—-free labor to help their already-rich owners build more wealth.

Interstate Slave Trade

The U.S. Congress outlawed the African slave trade in 1807. Transporting people from Africa for slave trading after Jan. 1, 1808, was punishable by death in the United States. It was still legal, however, to buy, sell and transport slaves within the country for almost another 60 years until after the Civil War.

During that time, the purchase and sale of people like Willis, Hector, Jack, Adam, Maria and Mary was a large part of the economies of the southern states, and particularly in the major port cities along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.

Eli Whitney's 1793 invention, the cotton gin, forever changed the agriculture and economy of the Gulf Coast states, and the slave trade. Weather conditions were perfect for cotton in the country's most tropical region, and cotton farms began to spread across the southeast like wildfire in the first half of the 19th century.

One problem sprung up with the white-fiber plant, though: Cotton took a lot of hands and a lot of time to pick. So as more cotton fields were planted, farmers needed more workers to pick the product. And there were a lot more cotton fields every year.

Between 1820 and 1830, cotton production in the South nearly doubled. It doubled again in the next decade.

Cotton didn't grow as well in Atlantic Coast states like the Carolinas and Virginia or in more northern slave states like Kentucky, so as cotton production increased in the southern-most states, plantation owners in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama grew in wealth and land holdings.

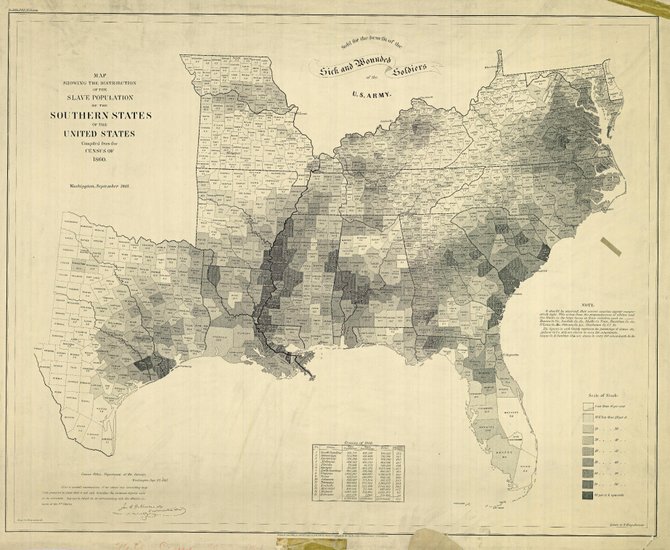

Because they could not legally bring more slaves from Africa, they bought their slaves from states that grew crops like tobacco and rice, which needed fewer workers than cotton. As a result, the slave population in Maryland declined from 1830 to 1850, and Virginia's was steady. Meanwhile, Louisiana's slave population more than doubled, Alabama's almost tripled, while Mississippi's quintupled.

The fastest way to transport the slaves was by boat, so Atlantic port cities like Charleston and Norfolk, Va., became slave-shipping hubs. Most were headed to New Orleans or other Gulf of Mexico ports, such as Mobile, Ala.

These cities flourished from the purchase and sale of human beings. As cotton production grew, the slave population followed step-for-step. Nowhere was this truer than in Mississippi, the country's largest cotton-producing state by 1860. According to that year's census, the last before the Civil War, the slave population of the state outnumbered the white population 436,631 to 354,000.

The only thing that stopped the growing flow of human trafficking through these port cities was a four-year fight between the northern and southern states now known as the Civil War.

By the time Mississippi seceded from the Union in 1861, slavery was so ingrained in the state's economy that the state's leadership could not imagine a world without it. In the state's 1861 Declaration of Secession, the third paragraph calls slavery "the greatest material interest of the world." It further explains that slavery was a necessity for the state's agricultural economy because "by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun."

The dependency on slavery, which helped make Mississippi one of the wealthiest states in the Union by 1860, led to a deep racial divide across the South that saw little bridging for the first 100 years after the Civil War, until the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s.

Now, nearly 150 years after its abolition, slavery's effect can be seen, heard, felt, smelled and tasted throughout the Gulf South's heritage, history and culture.

Some people, though, think it is time for that legacy to have an official home.

A Matter of Heritage

Lloyd Lazard believes he knows what that home should be. At 71, the New Orleans native's small frame is topped with hair that has begun to turn white on the sides. His glasses and salt-and-pepper beard do not hide the wrinkles in his dark brown skin left from years of work and stress.

For more than 15 years, a large portion of Lazard's work has been toward his dream—to build a Slave Ship Museum in his home city, and a sister museum and national park of Mississippi Delta Region heritage and culture in Jackson. He said there is a public law that not only supports, but mandates, his vision.

The Lower Mississippi Delta Initiative gave Lazard the idea for the museums in 1996. Two years earlier, in 1994, Congress had enacted Public Law 103-433, which under the LMDI calls for the recommendation and implementation of both a Native American and an African American Heritage Corridor and Cultural Center to be built in the Lower Mississippi Delta Region.

After reading the law, Lazard began searching for possible locations for the center in New Orleans. His research soon turned into his life's passion. When he speaks of the museum and cultural center, Lazard's deep voice is saturated in confidence and conviction that the project is the right thing to do for all of the Lower Mississippi Delta.

"We live here," Lazard said. "Our life is for the future. What happened in the past is the past, but we've still got to interact with the past to make it to the future. The knowledge and context of where we're trying to go is to bridge that gap, so there can be understanding as we move through the 21st century."

Beginning in late 1990s and continuing into the current century, Lazard wrote letters to bishops, presidents, governors, congressman, federal departments, school boards, port authorities, planning commissions and anyone else who might be able to help his dream become a reality.

Lazard's vision of the project includes combining the Native and African American museums by creating a Delta Region national park and museum in Jackson, where all races in the region's culture and heritage would be taught and celebrated.

Jackson would house the headquarters of the Delta Region Heritage and Culture Corridor. There, visitors could encounter educational exhibits covering aspects of the history and traditions of all of the races and ethnicities that helped build the Lower Mississippi Delta, from the French who first colonized the area in 1699, to the melting pot of the United States of America in this century.

Like the new lives of countless African American slaves during the slave trade, the corridor, Lazard said, should begin in New Orleans. There, he proposes that the National Park Service, which would run the operations of the museums, build a full-size replica of a slave-era ship used to transport Africans to America. The ship would serve as a large part of a museum, educating visitors on aspects of the slave trade, the heritage and culture of the slaves, and how they helped form the culture across the Lower Mississippi Delta.

In the ship, the visitors could see first-hand what the perilous trip across the Atlantic Ocean was like for millions of Africans snatched from their homes. They could see the cramped quarters, where thousands of slaves were chained for months at a time and learn why hundreds of thousands died before ever reaching the shores of the New World.

Between 2000 and 2005, Lazard's dream led him to write letters to former President George W. Bush, the National Park Service and former Gov. Haley Barbour, among many others. Bush, NPS and Barbour, as well as the Port of New Orleans and New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond, responded with letters of support for Lazard's vision.

"I appreciate your interest and thank you for sharing your thoughts with me," Barbour wrote in a letter dated Feb. 21, 2005.

"If I, or my staff, can be of assistance to you in any way, please do not hesitate to contact me," Barbour added.

None of Lazard's contacts offered solutions, though, to the sky-high hurdle that stands in the way of the multi-million dollar project: funding.

Where's the Money?

While Public Law 103-433 created means to fund the planning stages of such a museum and cultural center and also improvements to exhibits, it did not create funding to build such massive projects as the ones Lazard has proposed.

It did, however give the Secretary of the Interior specific orders for requesting funding from Congress for the museums:

"The Secretary, in consultation with the States of the Delta Region, the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Director of the Smithsonian Institution, the Lower Mississippi Delta Development Center, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and appropriate African American, Native American and other relevant institutions or organizations in the Delta Region, is further directed to prepare and transmit to the Congress a plan outlining specific recommendations, including recommendations for necessary funding, for the establishment of a Delta Region Native American Heritage Corridor and Heritage and Cultural Center and a Delta Region African American Heritage Corridor and Heritage and Cultural Center with a network of satellite or cooperative units."

Through LMDI, the National Park Service provided Lazard with a $25,000 grant in 2005 for a feasibility study on the National Slave Ship Museum. The Urban Design Research Center and Urban League of Greater New Orleans conducted the study. The study's findings are 34 pages long, plus nine pages of conceptual floor designs. The New Orleans City Planning Commission created a separate 30-page New Orleans Riverfront Vision 2005, which included a slave-ship Museum.

UDRC proposed in its study that the NPS build the museum at 1600 S. Peters St. in New Orleans, at the site of the former Entergy Market Street substation.

The six-story substation has more than 69,000 square feet per floor. Two tall smoke stacks stretch out of the top of the now-empty building. The study states that Entergy had the Slave Ship Museum as part of its plans for the future of the site, which is located on the banks of the Mississippi River near the Port of New Orleans. As is required in Public Law 103-433, the plans included musical, folklore, literary, artistic, scientific, historical, educational, and political contributions and accomplishments of African Americans in the region.

Along with an authentic slave-ship experience, the museum would include exhibits of art, books, and other artifacts compiled by the National Park Service and participating university and college departments of history and archeology.

A theater and music hall would present performances of traditional African festivities, as well as the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra and Mardi Gras Indian Tribes. A 6,000-square-foot restaurant would serve traditional African dishes and Creole dishes from the New Orleans region.

It also included local university backing. Southern University at New Orleans, under biology professor David Adegboye, would establish a DNA laboratory where descendants of slaves could trace their ancestry, a museum of organisms relevant to the region, and a molecular biology laboratory at the museum.

SUNO, which has Louisiana's only department of museum studies, also proposed housing the department in the Slave Ship Museum and using the facility for graduate-level students.

The UDRC study was far from comprehensive, though. It contained basic floor plans, but lacked artist renderings. UDRC included price estimates, to the tune of about $75.6 million, but not precise figures or bids from contractors for the cost of the project.

Nearly $58 million would go toward renovations, and UDRC estimated it would cost about $6 million to build the slave ship replica.

The study also failed to address Lazard's ideas beyond New Orleans, namely the sister museum in Jackson.

According to the study, UDRC needed another $350,000 to compile a complete feasibility study. In August 2005, Lazard submitted a request to the NPS for further funding through LMDI to finish the study and begin construction on the museum. In a letter to Lazard, Patricia Hooks, the Southeast regional director of the NPS, wrote that NPS could not afford to provide more funding, because it gets a "small amount each year" for the LMDI.

"Expansion of the Delta Initiative beyond this small grant program must be done through the congressional appropriation process," Hooks wrote. "Given the overarching need to address the condition of some of our parks' natural and cultural resources and support facilities, we are currently not in a position to advocate diverting funding for these high priority needs to other activities."

Then, in August 2005, the same month Lazard wrote the NPS, Hurricane Katrina destroyed much of the Gulf Coast, and Lazard's 11 years of lobbying and planning was quickly washed to the back of everyone's mind.

After the initial shock and confusion of Katrina washed away, Lazard had to face medical complications that kept his dream simmering on the back burner a little longer. Recently, though, a now-healthy Lazard is back on the battlefront, lobbying everyone he can find to get funding for the museums he believes will be a vital part of the culture and economy of the Gulf South region.

Lazard said that he believes spreading the word of Public Law 103-433 and helping get heritage and cultural centers built is his life's mission.

Lazard Comes to Jackson

Jackson was founded in 1821 and named the state capital the same year. The municipality soon became an urban city due to its newfound status as the seat of state government, as well as its strategic location..

Prior to the Civil War, slaves were brought to Jackson mostly by way of New Orleans and Natchez, the state's largest slave market. After buying slaves in Natchez, owners would often bring slaves to Jackson via the Natchez Trace.

Though the largest slave populations belonged to plantation owners in the state's southwestern counties along the Mississippi River, in 1860, Hinds, Madison and Yazoo were among 16 counties with more than 10,000 slaves. In Jackson, most slaves served as domestic servants or manual laborers.

Lazard brought his proposal and request for funding support before the Jackson City Council at its regular meeting May 15. At City Hall, Lazard said that the concept for the Lower Mississippi Delta Region corridor is to show the region's entire history, including Native American life and the French settlement of Biloxi in 1699 to the present day.

"What we are proposing is to create the national park for this project, The Delta Region African American Heritage National Park and Museum of the Delta Region, in Jackson," Lazard said. "What we are intending to do, by the grace of God and cooperation of the city of Jackson, is to develop two museums, one in New Orleans, one in Jackson, Mississippi."

The Jackson museum would house the national headquarters of the Lower Mississippi Delta Heritage and Cultural Center and Corridor in Lazard's plan. Like the museum in New Orleans, the Jackson Museum would house music and theatrical performances, as well art, literature and artifact exhibits of African and Native American culture.

Lazard said if the local governments of Jackson and New Orleans don't act, the federal government will not do anything to enact Public Law 103-433 and build the museums and culture centers the law mandates.

"Since 1996, the law put on me the vision of how to implement (this)," Lazard said. "I'm here today to talk to you all to help bring this into reality."

The plans are in place, Lazard said; the only problem is funding.

"The reason there is a lack of funding is because there is a lack of request for funding," Lazard said.

City Council members did not comment on the project at the meeting. Ward 2 Councilman Chokwe Lumumba, who invited Lazard to speak and added his presentation to the May 15 agenda, is going to present a resolution to the Council in support of building the Lower Mississippi Delta Region Culture and Heritage Center in Jackson.

Museums Thriving Elsewhere

While the large expanse of Lazard's proposal is unprecedented, slave-trade museums, public and private, exist on a smaller scale in the U.S.

In Charleston, S.C., one of the nation's busiest slave-trading hubs up until the Civil War, the city owns and operates a museum located in a former slave auction house, built in the 1850s.

Tony Youmans, interim director of the Old Slave Mart Museum for the city of Charleston, said the museum is a popular tourist destination. Visitors get a unique experience, he said, because the museum is site-specific. There they learn about the slave trade in Charleston both before and after the abolition of the international slave trade.

Anywhere from 100 to 200 people visit the small museum every day, Youmans said, at $7 per person and $5 for students. A large portion of its visitors are senior citizens and international tourists.

In Sandy Spring, Md., a small, entirely volunteer group runs a privately owned museum dedicated to educating the public about the lives of slaves in the area. Winston Anderson started the Sandy Spring Slave Museum and African Art Gallery, located about 20 miles north of Washington, D.C., in 1988 from a collection of artifacts he had amassed over a number of years. In addition to his collection, the former ship builder created a model cross-section of a slaving clipper-ship, which gives museum visitors a small look at what conditions were like below deck for slaves.

The museum also purchased a former slave residence from a nearby farm and relocated it to the property. There, visitors get to see the cramped quarters that often housed one or more entire families.

The small, private museum is open to the public by appointment only. Anderson's daughter, Laura Anderson Wright, now heads the board of volunteers who run the museum. Its most common visitors, she said, are school children on field trips and senior citizens.

"It is definitely a community museum," Wright said. "In an area that has the Smithsonian (Institution) within 30 minutes from us, you're not going to, nor would we ever try to compete with museums of that caliber."

Wright said heritage tourism has become more popular in the area since the economic downturn in 2008. Many people are looking for things to do in their community or within an hour's drive. That has brought a lot of local visitors to the Sandy Spring Slave Museum in recent years.

While a small museum like Sandy Spring may only draw tourists from neighboring towns and cities, Lazard has proposed something far greater for Jackson and New Orleans. With the funding, research and cooperation of multiple colleges and universities, as well as federal, state and local governments, museums of such high caliber could draw in crowds from all over the world.

With performances that encompass our region's culture and history in traditional music, dance and art, visitors to the Slave Ship Museum and the Delta Region Heritage and Culture Museum would be entertained by world-class performers while learning about our rich heritage in the arts.

From the fields of archeology, history and genetic biology, the museums could provide comprehensive learning experiences to teach children and adults about the affects slavery and the people involved have had on this region of the country and where it is today.

DNA testing could help visitors find ancestors who were slaves. A pair of shackles could teach a child about the bonds of slavery. Photos, artist renderings and literature could teach visitors about the abuse, mistreatment and dehumanization of slaves.

All of this could be used to educate us about our past, to assure we don't make the same mistakes in the future, Lazard said.

Lazard will continue to lobby everyone he can to try to see his vision of these museums realized. He said he knows it likely will not happen in his lifetime. All he can do, he said, is make sure as many people as possible know about Public Law 103-433 and the possibilities it provides before he dies.

He is trying to be all any of use can be, he said, a tool of progress.

"We are living in a period of change," Lazard said. "All we are is instruments of change."

Related Stories

Big Plans, Little Progress