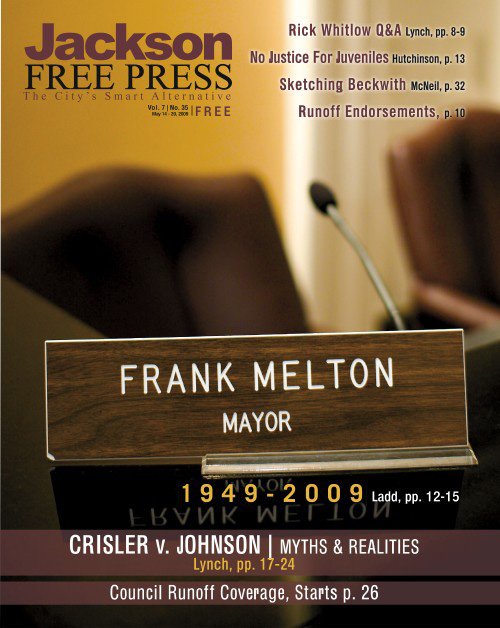

Mayor Frank Melton and I disagreed on many things, especially the way he ran the city and his style of "crime-fighting," but we met in the middle on a few things.

One of them was his dog Abby.

I first met Abby in April 2006 when Mr. Melton invited me into his home to meet the young men who lived there, have dinner and then go on a nighttime ride-along in the Mobile Command Center, the first of two I did with him. (He invited me on many; "We gone roll tonight, Donna!" he'd announce to my voicemail, usually after about 10 "missed calls" from his number).

Abby was mean-looking at first glance; she was, after all, a rottweiller. But I have a way with dogs and all animals, and it didn't take long for me to become fast friends with Abby. At Mr. Melton's house, she would follow him around, dragging her leash, or play with the bodyguards in his huge bedroom as he and I spoke in there at a table on one of my visits to his Northeast Jackson home.

Or, on the ride-alongs, she would trot obediently with Melton as he marched her on a leash toward a line of traffic on Bailey Avenue during what I would think of as "joy searches"—he didn't really seem interested in finding anything—or onto the porches of houses where he would burst in without a warrant, usually ending the visit with laughs and lectures.

Several times, I put myself on Abby patrol as Melton and the bodyguards suddenly leaped from the Mobile Command Center to flex their muscles (and sometimes guns), leaving her close to the busy street we were parked in. I would grab her leash and scratch her head, thinking that she might look just a bit relieved that she was left behind that time. She was, after all, an old dog.

Melton himself told me that Abby was mostly for show on the ride-alongs—that she wasn't really a "police dog," but his long-time animal companion.

I missed the visit to Albert "Batman" Donelson's mother's home on April 9, 2006, even though I joined Melton's entourage afterward that night. Apparently, Abby had helped scared the bejeezus out of her when Melton, the bodyguards and their submachine guns had marched up on her porch, with him yelling through the door.

But like much with Melton, Abby wasn't what she appeared to be. She was gentle and part of the facade of the armed man in the bulletproof vest who declared to me on his first ride-along, "Donna, you know what? I run Jackson!" Then he snickered, and added, "I do it in a weird way, but I run Jackson." You can then hear him on the tape telling Abby to stay out of the street.

Those were in the early months of Mr. Melton's mayoral tenure—back when he really did do what he wanted, just as he had in Jackson since he arrived here in 1986, and befriended then-Mayor Dale Danks and started riding around with police officers so he could connect with the young, needy men of Jackson. No one stopped him.

In this city, Melton became larger than life.

‘Call Me Frank'

Frank Melton did not lead a charmed life, exactly, but he could be incredibly charming.

When I first started covering the then-mayoral candidate in early 2005, he was nothing to me. He was another candidate, a "folk hero" to hear many long-time Jacksonians tell it, who talked straight about crime and drugs and the city's problems, especially those perpetrated by his fellow African Americans. To me, he was someone who had an amazing ability to say what people wanted to hear, and to make promises he couldn't possibly fulfill. What was remarkable was how much people believed him—or desperately wanted to.

It was as if an entire city—or a lot of it—thought they had found a man who would single-handedly solve all its problems so the rest of its residents wouldn't have to worry themselves over hard stuff like poverty, and crime,

and education.

I had missed Melton's "Bottom Line" years in Jackson, and so I went at Melton with fresh eyes and no preconceived notions.

I was surprised by what I found, both good and bad.

In the early months, I didn't spend a lot of one-on-one time with Mr. Melton, as I have insisted on calling him for four years now, even as he told me every single time he heard me to "call me Frank." But I refused to succumb to his charms, which I quickly learned had a way of fooling people, as charm can do.

At first, during his campaign, I was surprised to see how much of a protective unit he kept around him at all times, and I don't mean just armed bodyguards. He had that sister-in-law, Carolyn Redd, in from Texas to deal with his public relations, and she just tended to raise my suspicions with her defensiveness about him. (Current campaign folks, take note.) It was as if his people were afraid to allow him to be alone with me, for me to ask him questions, for him to answer.

But Melton and I managed to end up in the same place quite often, and we had many intense conversations. The first came when I kind of slipped into a breakfast at BRAVO! restaurant during his campaign, one held for rich white ladies of North Jackson. (Redd didn't recognize me at the door; she's not from here, after all.)

It was at that breakfast that I started seeing the complexity of Melton as he and the ladies brought up odd and disturbing "rumors" about himself from the past and then laughed them off, blaming "the police." Afterward, he and I spoke one-on-one for the first time, with him challenging me to look into his past. I would fulfill that promise over the years, and what I reported alternatively made him mad at me and led him to tell me that he respected my work, as he told me most recently in March in his City Hall office for our final interview.

He would often tell me that "they" did not want him talking to me, but that he had decided to anyway.

After Melton and I spent many intense hours together in March and April 2006—in his office, his home, the Mobile Command Center and on the streets of Jackson—I truly started to understand how charming he could be and began to understand how some people seemed to be so mesmerized by him, as if he had scattered gold dust on their heads.

"I have my Melton force field up," I'd tell people after meeting with him.

And I did. When I would arrive to meet with Melton, I would brace myself, knowing that we would laugh, and rib each other, and make bad jokes, and even cajole. (At least I would cajole; I got him to allow me and my photographers to go on the Mobile Command Center by saying repeatedly, "Please, Mr. Melton. Pretty, please." Photographer Kate Medley said it a few times, too.)

At one point in his bedroom sitting at a table with him and then-Chief Shirlene Anderson and Assistant Chief Roy Sandifer, with the bodyguards chasing Abby around the room, he was going on about something, chuckling away, and I suddenly yelled out, "You are so full of sh*t!" As my eyes got big at what I had just said to the mayor of Jackson, he and the rest of the group guffawed at me.

When I left Mr. Melton, I had to detox from his charm. It's so easy to think about the soft, funny, OK lovable side of him when you should be thinking about the constitutional rights of the people he targeted—the people on the other side of his force field. So many times I've had to reach in, pick up my brain and turn it to "the rest of the Melton story," so to speak.

I also grew to realize that his charm was likely his greatest strength and his most challenging curse. It too often shielded him from reality.

A Lonely Man

Mr. Melton told me more than once that he was a lonely man. He said he didn't have many friends.

Early on, that was hard to understand. He was always surrounded by people, it seemed—adoring police officers, his chiefs, the bodyguards, young men of Jackson. How could he be lonely?

But, gradually, I grew to understand that most people around Mr. Melton either needed him, or just wanted something he could give. Maybe it was money, maybe it was prestige, maybe it was protection or even silence. There had to be a reason that he lived far from many of the people who likely loved him the most, surrounded by people who let him say what people wanted to hear, and answer him with what he wanted to hear.

I believe that Mr. Melton's disarming charm drew the wrong people to him, for the most part. He and I discussed in March that he was often surrounded by yes-people who wouldn't challenge him enough. (And, I would argue, wouldn't get him enough help.)

Sure, the responsibility lies with him for drawing people around him who would tell him what he wanted to hear, find a way to help him do what he wanted to do, and help him cover up things he did that he shouldn't have done.

But, Frank Melton is nothing if not a massive tragedy. He is so much bigger than one charming politician. I've said for years now that he is a symbol of a broken city in a broken state. I'm not sure he really could have lived, or at least existed as he did, somewhere else.

Mr. Melton drew his power in all its forms from a city, and a state, where so many people have refused to take responsibility either for creating or for aggravating our problems. He hated poverty, especially in the black community, and he despised the broken-down houses that dot our city, in large part because absentee owners get away with leaving them there for the government to deal with (or keep making money off them).

But his impatience, and probably the yes-folks with forked tongues, kept him from using his charms to really do something about that poverty. He managed to assemble a rather unbelievable rainbow coalition of supporters, but he did not know how to help them find common ground. Instead, his campaign—and later his administration—was plagued with petty vindictiveness, turf battles, slammed doors and selfish grabs for power (and bond money).

He also seemed to have an incessant need to do it all himself and get credit for doing it himself. One of the more puzzling conversations I ever had with Mr. Melton happened after we featured Will Jemison, a young city administration employee who worked with youth, as our Jacksonian profile in the paper. He called me in a tither, upset at the feature.

"How many kids has he ever sent to college?" he demanded. I sat puzzled, holding the phone.

"He didn't say he had sent anybody to college, Mr. Melton."

Mr. Melton would readily lambast groups such as 100 Black Men for not doing enough for the young men of Jackson, but wouldn't use his own capital to form programs to help the most young people. Everything had to be personal, to a fault.

By most accounts, Mr. Melton did do a lot for many young men and some young women. I've gotten to know young men—former criminals—who say that he saved their lives when no one else would pay them any mind. That he taught them to swim, gave them money, spent time with them and moved them into his home.

Some of them sat through his federal trial, and I know they are very upset at his death. My heart breaks for them, and I wonder who will take them seriously now and try to help them stay out of jail, to start over.

But as always with Mr. Melton, there is always another side to his coin. Sometimes when I need to shake off the Meltonian force field, I think of Evans Welch, the schizophrenic drug user who lived at 1305 Ridgeway St., the tragic young man who hurt himself much more than he had the ability to hurt others. Everyone knew that. Melton knew that.

Still, Mr. Welch became Melton's public symbol of all-things-evil in poor parts of Jackson. And the landlord of the duplex—Jennifer Sutton—was transformed into a greedy plaintiff wanting everything she could get from Melton and the taxpayers after he got intoxicated and gathered teenagers and cops to sledgehammer her property. Melton attorney John Reeves' personal (and I would argue racist) indictment of her in Melton's federal trial earlier this year is one of the more disturbing pieces of rhetoric I've heard in this state in a long time.

Even as the man who would save the black people of Jackson sat there and listened.

Dying with Dignity

When I heard on primary night that Mr. Melton had gone into cardiac arrest, I wasn't really surprised, although he always did manage to surprise me with his specifics—such as the sledgehammers on Ridgeway, or his health failing as the polls closed.

I immediately felt as if a very difficult, stubborn, incorrigible member of my family was gravely ill. During the trial and then when he and I met in March in City Hall, it was clear that he was very frail. He seemed to be telegraphing that he did not believe that he had long to live, that he was going to go down fighting. He said he didn't have anything else to live for so, yes, he was going to run for office again.

"I think I can handle another term. If that's not the case, Donna, I'll tell you what," he said. "After 23 years, the only thing I'd ask of the voters of Jackson is that if I'm not going to make it health wise, please let me die with dignity. Just let me have my dignity in death. Let me be doing something to help other people, and if it doesn't work out, it doesn't work out. But I'd really appreciate being able to move along with my dignity intact."

I've thought often about those words—"with my dignity intact." What did he mean by that? Maybe he wants us to think about his best side and not to dwell on his negatives. Maybe he wants us to move past the parts that were distasteful and perhaps hurt people, even as we remember what he did for many people, especially those that no one else had bothered to care about.

Personally, I don't believe that allowing Mr. Melton to die with dignity means we have to forget anything, or stop trying to understand the full complexity of Frank Melton—and I'm not convinced he wants us to. Sure, he would love the glowing things being said and written about him now—I mean, he was a narcissist if I ever met one, and a rather lovable one—but I also think he bore the burden of what the community had hoisted on him, how we as a whole exploited his weaknesses in order to abdicate our own responsibility to each other.

The Frank Melton I talked to in March still believed in himself and his heart, but there was also guilt in there about things he has done wrong, and toward people he's hurt, I think. He never knew how to tell the city to stop using him as a receptacle of our demons, but I believed his eyes cried out for that. I believe he long begged for help that the city did not know how to give him.

Maybe it's why he liked me, no matter how hard I was on him. Maybe he knew I would tell the truth about him in all its complexity and challenge the city to face its role in this tragedy. Or at least try to.

Or, maybe he just liked to joke and laugh with me. Then again, maybe we both just loved his dog.

Goodbye

Abby died on Monday before Melton went into cardiac arrest on Tuesday evening.

In March, the toughest part of our conversation was about Abby. I would most always ask about her, even if Melton and I were then butting heads about something else. It was one of those topics, along with talking about the young men in his home, that always lightened him up.

In March, he told me it was just the two of them these days.

"There's nobody there now but Abby and myself, and I usually take Abby down to the pool with me. Not that she can do anything. Some days she'll get in and swim; some days she'll just run the bank when I'm swimming," he said.

Times had changed a lot since I visited Melton in his home, young people all over the place—some looking happy, some afraid, some suspicious—guns hanging in his bedroom, badges on his dresser, laughing bodyguards, baked chicken on the table. His loyalists from the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics have moved on, too: Chief Shirlene Anderson has long since been forced out of a job she could never handle—at least as the second to Frank Melton—and Assistant Chief Sandifer succumbed to cancer.

Abby had been with Melton through thick and thin, for most of the time he lived in Jackson. He had taken her to the vet, who wanted to put her down. But the mayor said that he wanted Abby to die at home with him at 2 Carter's Grove.

On Tuesday evening, shortly before the polls closed, Melton was found in his home, unresponsive. He had gone into cardiac arrest, before learning the outcome of an election that he would ultimately lose.

May Mr. Melton rest in peace, and his memory in all its complexity inspire us to a better day. I certainly will miss him.

Previous Commentsshow

What's this?More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.