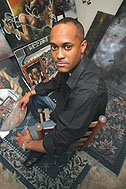

"I always knew I could draw, but I didn't know what I wanted to do with it," 29-year-old Tony Davenport reflects as he looks off into the distance.

Davenport's two-bedroom apartment is also where his studio is housed. Completed and unfinished art pieces fill the dining room; the walls boast pieces of his own work and family photos.

Inspirations

Coming from a family of untrained artists—both Davenport's father and uncle are avid drawers—he recognized his own talent in elementary school. Drawing cartoons fascinated him. Taunted about this absorption by his classmates, Davenport nevertheless kept drawing. He didn't, however, begin to take his talent seriously until he entered middle school.

"I was watching 'Good Times' one day and thought, 'I can do that.'" As the credits rolled at the end of this first African-American situation comedy, the artwork of Ernie Barnes was featured. Years later, Davenport was reacquainted with Barnes' artwork. "It was divine. Things happened the way they were supposed to," he says. "I saw a picture on the cover of the Marvin Gaye album 'I Want You,' and it was Barnes' work." He displays the tattered album cover like a proud schoolboy. "I bought it for the cover, but I listen to the music."

As the artist begins to talk about our "divine right" to produce and enjoy art, one can't help but begin to feel his passion.

"Anytime you can take a sheet of paper and make it make sense, it's a gift," Davenport says. "It's not about black or white, rich or poor; it's about a spirit inside of you. You create what you feel. You know when it's right. It's personal."

The first time Davenport recognized that he'd done a good job was in 1992, during Vicksburg's annual Riverfest. There was a contest for local artists to design a T-shirt, and he won. He says he didn't think he would have a chance at winning, but he tried anyway. Not only did he win, but he was the youngest person ever to have won. That day was the day he knew he was an artist.

The next step was to develop his skills. After he became dissatisfied with drawing cartoons, he directed his attention to fine arts at Hinds Community College and became determined to learn to paint. Davenport says that while at Hinds, he set his mind to "learn everything beyond drawing about art, because I wanted to be versatile."

It goes without saying that he encountered a diverse and enigmatic group of people after transferring from a community college to a university. But aside from the vicissitudes of academia, he explains that he learned not only lots about people but also himself while at the university. The unforgettable lesson: "You're in charge of your own destiny. You can't rely on anyone else." Davenport's art began to mature as he himself did.

The Big Boom

Davenport says that the art climate in the metro area is rich, but more should be done to reach out to those who are trying to produce. Some are looked over because of what college they attended. "The city is ready for a complete artistic boom. Many believe it's already come, but it hasn't," Davenport says. "It's still to come, and I want to be a part of it."

To ensure the boom comes, Davenport is committed to keep producing and be at every event that gives artists an opportunity to showcase and promote art. How can a non-artist contribute? Support events that go on throughout the city. "People support the arts and don't know it. ... People who don't create are the biggest supporters."

Davenport also reports to Powell Middle School each day to teach eager students about visual art. He also gets to play catch-up.

"Appreciation for art should start at a younger age," Davenport says. "The problems that teachers encounter oftentimes are because kids are doodling. And it's not so much that they're bored, but that they need to expend energy. If (educators) are able to mold that energy into something meaningful, it can go a long way." He believes part of the problem with many public schools is that the curriculum doesn't offer enough electives.

The problem isn't new. At Vicksburg High School, he wasn't exposed to much art before graduating and going to Hinds and JSU. "I didn't even want to go to college at first, but my teachers encouraged me," he says.

Artist in Black

"I don't want to be characterized as an African-American artist," Davenport says. "I love my race, but I want to just be an artist. I want people to stop looking at me and start looking at what I have to say."

Davenport says that he is faced with an unavoidable challenge of getting people to accept his style and subject matter, but he sometimes also feels plagued by producing art from a black male's perspective. "I do have socially charged paintings," he says. "As an artist you have a license to say what needs to be said. And if you create it, you need to be prepared to back up what you're saying." His greatest frustration is being locked into one style of painting or expected to express himself in a certain way because of his race.

"Don't expect me to paint people in the cotton fields just because I'm black," he says. "I create for everybody, not just for black people because I'm black. You have to take chances and expand your horizons. Being stuck in one gear doesn't get it. You have to reach out even if they're not reaching back to you."

Tony Davenport will exhibit at Arts, Eats and Beats in Fondren on Thursday, April 20, starting at 6 p.m.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.