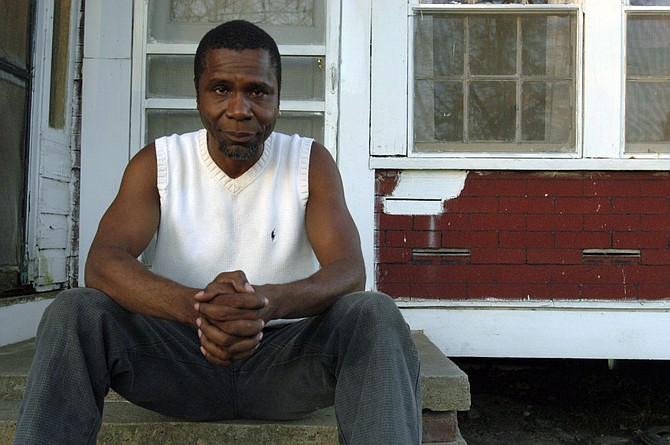

John Ellis Ishmael Briggs Be sits outside his family home in Roxie, Miss., that his parents had to protect from the Ku Klux Klan in the 1960s because his father, Rev. Bennie Clyde Briggs, tried to protect and help local black people. The home has a bullet hole where the Klan shot from the outside into the wall over where Briggs Be's little sister slept. Photo by Kate Medley

When Mary Geraldine Briggs heard a horn blaring outside her small house, under shady oak trees on Highway 84 in Roxie, Miss., she would go get the shotgun and head to the door to protect her family. The horn was the signal from her husband, Rev. Clyde Bennie Briggs, that a carload of Klansmen was on his tail again. His wife was instructed to do anything she needed to do to protect herself and their six kids, and the one on the way. She was armed and ready.

Usually, Rev. Briggs would screech his green Dodge or his white Valiant, whichever he was driving, quickly in front of the house, and the Klansmen would roar on by. The bigots had done their job for the evening—they had delivered a strong message to an uppity black landowner that white supremacists in Franklin County would stop his efforts to help black people help themselves. It was 1964, and the Kluckers, as they were called by non-believers, were willing to protect themselves against an "uprising" by any means necessary.

What confounded the Klansmen—many of them merchants, factory workers, law enforcement officers—was that black Roxie was willing to do the same thing.

There Is a Season

Rev. Briggs was a tall, persistent man with a direct gaze and a booming deep voice that tended to articulate proclamations, not mere words. Unlike many black Mississippians of the era, Briggs had an education—he graduated from Natchez College in 1947 after returning from fighting in World War II—and quickly answered his first calling, and became a schoolteacher. But he wasn't just any teacher—he was an organizer before the word "organizing" became a dirty word in Mississippi. He was determined that young black people make something of themselves. To do that, they had to have a good education.

Briggs taught at the all-black Roxie School, which was just across the road from his house and a few houses east, before it was later firebombed. His former student Valerie Doris Norman (then Sanders) remembers how hard it was for young blacks to get an education in Jim Crow Mississippi, where the schools weren't equal, and most white people liked it that way. Many rural black kids had to farm, so the school year for them only went from October to March. This way, they could help with both planting and harvest seasons, meaning that even children of non-farming families like the Normans and the Briggses could only go to school six months a year.

Norman, now 69, remembers that the Roxie School had only two teachers—one for grades 1 through 4; another for 5-8. There were probably a couple hundred students there; many from completely illiterate backgrounds. Briggs dealt with them all equally, with firm charm, and he knew all their names, Norman said, sitting in her Roxie living room with pale-pink curtains and a baby-blue Cadillac—one of the big ones—under the carport.

"He was an all-around type of guy. He would walk around school and know what everyone was doing. He kept the children straight. They didn't get by him with too much," she said. Briggs felt strongly that young people had too much freedom, and they needed to be productive with their time. He helped start a baseball team and encouraged young people to try for roles they didn't think they were good enough for—like singing in the church choir or applying for jobs.

"He pushed you into whatever you needed to be," Norman said. "When you're young, you need that."

In the 1950s, Briggs faced new callings. "He began to pursue the change coming up with the Civil Rights Movement," Norman said. He was sent on that path by a discovery while teaching. "He found out that class rings were one price for black children, another for whites," she said. Black kids had to pay more..

"You need to know what era we were living in. It was difficult," Norman added.

But Briggs was known as a man who would do whatever it took to help his people—meaning all black people—get a leg up. He worked tirelessly, keeping detailed journals and lists of costs on everything from his car notes to his students' school attendance.

By the 1960s, Briggs had reached another season of what would prove to be a short but productive life. "He was called by God from the school to come into full-time ministry," Norman said.

In those days, a black pastor often ministered at several churches. Briggs was no exception, traveling day and night through several counties to shepherd his flock in five congregations, and start Sunday School classes and sports teams and youth groups.

Norman then attended Roxie Colored Baptist Church—now Roxie First Baptist Church—which was Briggs' home church, near where both of them lived. She had married young. But Briggs wasn't content to let her get caught up in simply caring for her husband and her own children.

"He pushed me," she said. "He'd say, 'Sister Norman, why are you not singing in the choir?'" When the assistant secretary of the church—a man—died in 1961, Briggs urged Norman's mother, Waddell Sanders, to apply for the job. She did.

This kind of relentless drive was what the black people of Roxie needed, Norman said. To her, Briggs is a hero—unsung, but a hero, nonetheless. "I'd put him with Martin Luther King, because he was that kind of man," she said.

Trapped by Kluckers

Rev. Briggs had more in common with Rev. King than his push to empower African Americans, however. He was also an enemy of the white power structure that wanted to maintain the status quo. In Roxie, as in most of America, the rules of Jim Crow apartheid were simple. If you were black, and you didn't rock the power boat, white folks would leave you to your business and might even appear friendly from time to time. If you were black, and you started acting uppity, wanting "communist" stuff like equal rights and good schools and better-paying jobs, you were a troublemaker and would be dealt with as such.

Briggs chose to be a troublemaker. So did many of his friends like J.L. Miller, a choir director at Mount Olive Church, near Kirby, for "60 some odd years."

"Reverend Briggs and I, we were carrying people to the county seat to register to vote at the time," said Miller, sitting on his Roxie deck next to his wife, Christine, a long-time teacher herself whom he calls "Baby." Only about five black people were registered in the county then, and like many blacks who served in the military in non-Jim Crow locales—even voting by absentee ballot while there—when Briggs returned from the service, he was appalled. "When he came back, he found that Franklin County was in the background (of the movement for freedom), and we teamed up and started taking people out to Meadville to register to vote."

Official Meadville wasn't amused. "We thought we had quite a number of people registered. But when it came time to vote, the people that we had thought was on the book was not on the book. So we started to make complaints," Miller said.

The noise they made captured the attention of the area's growing terrorist organization, he said, which had rebooted in 1964 with a vengeance. "Well, at that time, the Klansmen had moved in, and so they would try to block us. We would leave one direction and come back another to keep them (from following us)," he said.

This wasn't an easy feat, being that Klan members constantly watched people they suspected of activism. They even signed on some African Americans to help them watch, Norman said. "They did dirty things. They needed Uncle Toms."

"They had people watching us," Miller said. "We caught on to what they were doing, so if we had to go to Brookhaven, we would leave like we were going to the theater in Natchez. And we'd go around through the country... . Then we'd come back through Crosby and come up that way."

Sometimes the ruse didn't work, though, especially on stretches of road where it was hard to see who was waiting ahead—like "flats" between hills. One time, for instance, Briggs was driving along near a place known as "Roadside Park," and Klan vehicles encircled him—a horde of white men trapping one black man. "They thought they had Reverend Briggs hemmed up, but some kind of way somebody else come along and interrupted, so he was able to escape," Miller said. He believes Briggs would have died that night had the other car not come along.

Miller remembers another night when Klansmen, wearing hoods, trapped him after a choir rehearsal because they thought he had been to some sort of civil rights meeting. "They waited for me down there at what they call the Baby Branch." (The Baby Branch is a creek where a baby drowned once, giving the creek a reputation for being haunted.)

The Klansmen forced him to pull over, and five or six surrounded his car, as others waited in theirs. "I happened to have a car full of children. (The Klansmen) started talking, and the children started making a lot of noise. So they opened the road and let us go on by," Miller said.

At first, the Klansmen would sometimes cover just their faces with hoods, if they concealed their identities at all. Then they got more serious. "When they started to burning crosses and burning churches, they were in a hood and their robes," Miller said.

Eliminating 'Agitators'

Sometimes, though, local Klansmen would not cover their faces as they did their dirty work. One night, Norman heard her dog, King, barking ferociously outside. She turned on her porch light, and as she did, she saw the light go off at her mother's porch across the road. Then she saw a white Packard Clipper about 100 yards from her house. She could see two men jumping in the car, presumably scared by King, including a local man whose face was not covered.

Later, at church, Norman discovered that every other black house along the road had gotten a gift of a threatening flyer left on their porches. "They was real nice. They put a rock on every note," Norman said with a laugh.

Norman, whose home was armed in case an intruder came calling, was a bit bummed that she didn't get a flyer, too. "Let me see one!" she remembers saying to fellow church members at Roxie Colored, after she heard everyone whispering, "Did you get one?"

The Klan activity in the area was no joke, though. Even as other parts of the state—especially Neshoba County, where two white New Yorkers were killed along with a black man from Meridian in June 1964—captured more media attention (and would continue to do so for decades), southwest Mississippi was the heart of Klan country with FBI agents, not to mention civil rights activists, pouring into an area on the verge of an all-out race war.

Southwest Mississippi, with Natchez as the epicenter, has even been dubbed "Klan Nation," as so many Klansmen joined up in the 1960s. Many were part of the extremely violent White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which was said to order "eliminations" of prominent "agitators" like Michael Schwerner, based in Meridian, and Vernon Dahmer Sr., an NAACP leader in Hattiesburg.

Sitting in his living room in south Natchez in July 2005, former White Knights Province Giant James Kenneth Greer Jr. told the Jackson Free Press in his first media interview that so many young men joined the Klan back in the 1960s because they believed what they had been taught their whole lives—that "colored" people were inferior, violent, and a threat to white communities and schools.

"Young people tend to do stupid things, get themselves in trouble," he said of his earlier days, shaking his head.

The White Knights' fiery rhetoric and glorification of violence against blacks—Greer talked of the Cottonmouth Moccasin Club that only men "who had killed a black" could join—attracted many of the blue-collar men who went to work every day in plants like International Paper and Armstrong Tire & Rubber in Natchez. Like many of the Klansmen in the area—including Charles Marcus Edwards, now believed to have immunity to testify in the upcoming federal kidnapping case of James Ford Seale—Greer worked at IP. And he believed the hype then.

I Want Justice, Too: Re-opening KKK Cold Cases in Mississippi

Investigation by Donna Ladd and Kate Medley of 1964 murders that sent an old Klansman to prison

Greer also participated in efforts to scare away "agitators" with car chases and beatings, and was called before the House Un-American Affairs Committee on Jan. 14, 1966, along with other alleged Klansmen, including Seale and Edwards, to testify about the Klan's violence in Mississippi. (They all took the fifth and refused to answer questions.)

In his 2005 interview, the former Klansman talke about the confusion that led him to participate in such a violent organization. "I got in the Klan, and I talked Daddy into going to a meeting," Greer said then. "He told me, 'Son, that's a bunch of fools.' He was 100 percent right; it don't take but a few fools to mess up your whole world."

Greer described a world, a Klan nation, in which the sustaining mantra was resistance. The group would stop at nothing to protect what they held dear—segregation enforced by the law. "People in the South, especially people with young girls, kids, little girls, they just couldn't stand the idea—and I was one of them—of putting their children in school with them 'nigger boys.'"

By 1964, much of the violence was motivated by something beyond racism: The Klan was growing more and more paranoid about black people arming themselves to fight back.

'All the Negro Trouble'

On the evening of May 2, 1964, a state highway patrolman and a Franklin County deputy showed up in Crosby at the church where Rev. Briggs was working that day. They told him he had to return to Roxie with them so they could search the Roxie Colored Baptist Church, which he pastored, for a cache of guns. They said a source had told them that "a group of guns was hid in the church and some white men was going to bomb the church that night," as he wrote later in his journal, among meticulous lists of tithes and who was signed up for his church youth groups.

Later, under the headline, "Things Hapened in 1964 in Franklin County (sic)," Briggs wrote: "No guns was found in the church—but the law officers advised the pastor to see to the church being locked when all leave the church." (Briggs referred to himself in the third person in his journals.)

That wasn't the only significant event of Saturday, May 2, but Briggs wouldn't know that for a couple months. May 2 was also the day when Klansmen Seale and Edwards, of Franklin County, allegedly abducted Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore, both 19, from Meadville before driving them into the Homochitto National Forest just down the road from Roxie. There, according to FBI files, the group of White Knights beat them nearly to death, then later tied engine parts to their bodies and dumped them into the Ole River, an offshoot of the Mississippi River in Warren County, near Tallulah, La.

That story is well known by now. What is less comprehended, even as it seems to be at the heart of the federal 2007 indictments against James Ford Seale, is that this was not likely a random heinous act. Instead, it is likely a tale of violent and persistent paranoia—the Klansmen were scared of violent "Muslim uprisings," and they were looking for guns that they believed African Americans were hoarding to use against them.

FBI files from 1964 tell the story. On page 3 of a Jan. 12, 1965, report about the story, the agency writes: "James Seale was heard admitting that he was the one who did most of the questioning of the two Negroes. He was also heard making the statement that he wanted to kill the colored Preacher Briggs, whom he thought was stirring up the Negroes in the Franklin County area."

The report continues: "It appeared that James Seale had been trying to get information from the two Negroes as to who was in charge of the Negro agitation in Franklin County. Also, the rumor had gotten out that the Negroes were bringing guns into Mississippi. The Black Muslims were supposedly getting the guns and were going to start an insurrection."

"He said it had been determined that James Seale and others kept beating the Negroes until one of them finally said the guns were in a church, and it appeared this had probably been said by one of the Negroes to stop the beating."

Later in the report, the FBI states that Clyde Seale, the Exalted Cyclops of the Franklin County Klavern and James Seale's father, said that the Klansmen were bent on knowing who was behind the agitation in the area. "During the beating, the two Negroes were questioned repeatedly and consistently about who was causing all the Negro trouble in Franklin County. The name that the boys kept using was Briggs, a Negro preacher at Roxie, Mississippi," the FBI attributed to the Seale father.

The 2007 indictment against Seale charges him with conspiracy because, according to investigators, he kidnapped Dee and Moore because he thought that Dee was involved with civil-rights activity and, therefore, would know who was hiding weapons. The indictment also revealed that, after the beating, the Klansmen are believed to have taken the near-dead young men to one of their farms nearby, while others got law enforcement to go search the church—an account that meshes with Briggs' 1964 journal entry.

It is unlikely, however, that Preacher Briggs would ever know why his church was searched that night. And it wasn't until 2005 that his family would learn that the Klansmen who likely killed Dee and Moore were also obsessed with their father, or that Briggs was named in the FBI documents. They learned that fact when they read the July 20, 2005, story about Thomas Moore's trip home looking for justice in the Jackson Free Press.

A Shot Across the Klan's Bow

"Until you printed what you printed, OK, we had always been led to believe that our daddy was killed for what he was doing with the Civil Rights Movement, because of what he was doing with voter registration," said John Briggs, a black Muslim who also goes by John Ellis Ishmael Briggs Be.

Briggs Be and some other members of his family have long believed that his father was killed for his work for black freedom in the 1960s. The official report is that Briggs, then 42, took ill suddenly on Jan. 18, 1965—from acute pneumonia and meningitis, his death certificate says—and died shortly after arriving at University Medical Center in Jackson.

The son has never bought the official report, believing for decades that his father was poisoned, perhaps by an "Uncle Tom" working with the Klan as Briggs was making his minister rounds. And although he cannot prove it, Briggs Be believes that the government covered it up. He says that his mother, who used to meet her husband at the door with a shotgun, believed that her husband may have been killed until she died in 1987.

Considering that the Mississippi state government at the time was funding a white-supremacist state spy agency, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, and feeding license-plate numbers of "agitators" like Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney to sheriff-Klansmen who planned to execute them, Briggs Be's belief is not outside the realm of the possible.

It is also not a certainty.

After reading the Jackson Free Press story about Thomas Moore's journey for justice, Briggs called the Jackson Free Press. "You're talking about my father," he said with a tone of urgency. "That's him in the FBI report. We didn't know about this." The story had not called Briggs by name, but had referred to the Klansmen's statements about a "black preacher in Roxie." Considering that Briggs was the preacher known far and wide for his Movement work, it was immediately clear to his family that their father was named in the FBI report. But no one had ever told them, nor had investigators been in touch with them over the years.

Even if he could not prove that his father was murdered, Briggs Be wanted his father's story told. So do others whose lives Briggs touched, as we would soon learn.

Courage of the Father

Sitting in the small house where he grew up in Roxie, where his brother Charles still lives, Briggs Be talked about the courage of the father whom he used to accompany on his rounds to churches and community members. What he remembers the most is his father's activism, and he tells a more militant story than is often told during Black History Month every year, when the virtues of a non-violent Civil Rights Movement are celebrated.

The truth is, many blacks in Mississippi—especially in the Klan-entrenched southwest part—did not win their rights by putting their children in front of water hoses and attack dogs. Many black Mississippians, like those in Roxie, claimed their American birthright by arming themselves and sending a message to whites that they would fight back, or even kill, to protect their families.

Briggs Be, who lives in Biloxi and does civil-service work and is building a cabin on land in Franklin County, remembers his father's association with the Deacons for Defense and Justice, a home-grown movement that began in 1964 when black men in Jonesboro, La., decided to protect themselves with guns rather than take a bullet for the cause. These progenitors of "black power" were arguably the shot across the bow that broke the back of white supremacy in that region (helped along by FBI infiltration and federal assistance that finally came, if belatedly).

The son also believes that there were, in fact, guns hidden in Franklin County, even if they were not found in the church that night. Earlier this month, he showed the Jackson Free Press a graveyard, a clay-bedded stream and an outhouse behind the now-abandoned church his great-grandfather built, Old Pine Grove Baptist Church, where he has heard that guns were hidden back then. He also tells of meeting Malcolm X on Chambers Road in the early '60s, where the chief spokesman for black self-defense had snuck into the area with other members of the Nation of Islam, dressed as a hobo, to meet with local men, including his father. (This newspaper has found no record of those meetings, but Malcolm X was indeed known to sneak into unfriendly areas to meet with supporters.)

Miller confirmed that the Deacons for Defense started forming in Franklin County in 1964, but he does not remember any visits by Malcolm X or guns being hidden in any particular place, although they were in every black home in Roxie, he said. In fact, Miller brought up the Deacons while talking about his work with the NAACP at the time, and without being asked about the clandestine group. "(The Klan) had got so bad, the blacks had got so afraid, that we started having a mass meeting at different churches and locations in different counties trying to (tell) people to don't be afraid. ... We were very lucky and able to organize the NAACP," he said.

Then he added: "So that kind of put a dent in the Klansmen because when we got organized, we had the Deacons for Defense. So (the Deacons) had weapons. And (the Klan) found out that we had those weapons. So they kind of like backed up." Miller said the Deacons scared the Klan by facing them down and even cornering them when they caught Klansmen following them. "We caught a couple of their men," he said. The Deacons didn't hurt the Klansmen, he said, but "talked kind of rough."

"So one of them told me, 'If you don't kill me, I'll never do it again.'"

Miller also remembers that, sometime after May 2, the FBI, too, came to the church looking for the guns.

A Different Kind of Deacon

Lance Hill of Tulane University has written one of the few books about the Deacons for Defense, compared to probably hundreds written about the non-violent Civil Rights Movement, which was more myth than reality for many in southwest Mississippi. "Reflecting class tensions within the African American community, the Deacons spearheaded a working-class revolt against the entrenched black middle-class leadership and its nonviolent reform ideology," Hill writes in "The Deacons for Defense" (University of North Carolina Press, 2004). The Deacons were girded by blacks who were no longer sharecroppers, and had shed the sharecropper mentality of "just taking it" from white people who mistreated them.

"Their political strategy was confrontational, disdainful of nonviolence and independent of white liberal control," he wrote. Hill explains that the Deacons were born in 1964 for two reasons: because the violent Klan militias were re-emerging as the terrorist enforcers of the white status quo, and because the federal government was failing miserably at enforcing civil-rights laws and helping blacks in the South. "The rise of white supremacist violence in response to desegregation made armed self-defense a paramount goal for many local black organizing efforts."

The Deacons weren't officially organized until January 1965 (the month Briggs died), but word about the need for armed self-defense had spread through black communities in the region through much of 1964, and self-defense groups started forming, even if they weren't officially sanctioned. It is likely that the Franklin County Deacons were an unofficial chapter, but that didn't mean they were less determined, or less armed.

Hill writes in his book that the Deacons formed to protect their families and other blacks, not to be an army of aggression. He quotes Natchez Deacons president and barber James Jackson speaking at a meeting, as seen in the documentary "Black Natchez": "I believe just like Martin Luther King and everybody else, I believe in non-violence. I really do, man. I think that non-violence is the only way to solve the problem, you know. On the other hand, I believe that our people should stop getting killed." He added that he did not hate whites. "I like white people; I like green people; I like any color people ... but when people is killing me off, killing my mother and my sister off ... it's time for us to do something."

The 'Myth of Nonviolence'

The Deacons' story has been told, but not often, and that part of Mississippi's history seems to end up on the cutting-room floor, leaving a narrative that reads "bad whites, helpless blacks, northern saviors"—what Hill calls the "myth of nonviolence."

Yet many older African Americans in southwest Mississippi know well the power the group wielded—near-Klan-like ability to scare a group of people of the opposite race when they showed up en masse in front of a meeting or a march or the home or business of someone being threatened.

In her book, "A Little Taste of Freedom" (University of North Carolina Press, 2005), historican Emilye Crosby credits the Deacons for keeping the Klan out of Port Gibson, for the most part. How? They showed up outside a community meeting where prominent whites were discussing whether to invite the group into town; the calm, armed black men seemed to tilt the scales against escalation. Much like Malcolm X did nationally, they even spread rumors that Deacons were going to destroy downtown and created a false minutes book that they planted for the sheriff to find. In other words, they fought back with what Crosby dubbed "psychological warfare."

It worked. "Deacons' self-defense and willingness to take up arms created space for non-violent protest and political activism," she wrote. "Moreover, in the process, they inspired many other blacks and provided a vehicle for the movement to achieve, at least in part, a number of goals without having to wait for court decisions or electoral victories."

In present-day Roxie, Norman nodded knowingly at a mention of the Deacons for Defense, as if the name of the group was as common to her as that of Dr. King. It is clear that she remembers living amid people in the 1960s who were willing to fight back. During the time when the Klan was burning crosses in the area, she remembers her own husband, Bailey, now deceased, saying: "I will not run. I pity the person who comes to my house to burn a cross. I'll leave them right there." Her husband kept a gun loaded. "We would not run from nobody," Norman said.

She also remembers good white people who were not cowed by threats, who would help their black neighbors. Her husband worked at International Paper, alongside many Klansmen, during a time when pushing for higher pay or a better job could get a black man killed. But he had a white supervisor from Louisiana who pushed him to better himself. "Whatever job they put before you," he told Norman, "you accept it, and I'll help you." By the time he retired from IP, her husband had the authority to fire people, even white ones.

Norman makes no secret that Briggs, and his courage, was a model for all of black Roxie. "He would face (Klansmen) head on. They didn't like it because he stood up," she said. Briggs risked his own family to "stand up for the black race, period."

She remembers Briggs proclaiming an anthem of self-defense from the pulpit not long before his death: "I will not stop. I will not be run off the road. I will run over them."

The Light Kept Burning

Rev. Briggs' journal from 1964, though, shows a Klan determined to knock him off his path. On May 24, he was coming home from a church service at New Bethel Baptist Church, east of Meadville. When he neared Roxie, two cars full of white men tried to stop him on the highway, but he would not pull over. They followed him to his home, and then one of the men got out "and did a lot of big talk and told Rev. Briggs that the next time they try to stop him he better stop."

Then, his journal shows, on July 13, the bodies of Dee and Moore were found. "On that same night, someone shot into the home of Rev. Clyde Briggs with a rifle," he wrote.

That night has lived in infamy in the minds of Briggs' family members and many of his neighbors. Peachie Morgan, then McCoy, is a 65-year-old woman who recently moved back to Roxie after years away in Florida. She was friends with Henry Dee, knew the Moore family, and grew up next door to the Briggs house. The remains of her family's home is still several hundred yards west of the house where Charles Briggs now lives. She remembers Briggs driving home at night honking his horn for his wife to get the shotgun. And she recalls vividly the night of July 13, 1964.

"I remember the night they shot up in the house. ... And that's when my father wanted to get involved in it, but my mom was afraid of that," she said.

Briggs' small daughter, Chasity, was already asleep in her bedroom on the north side of the house facing the highway when the white men came. They pulled over on the side of the road, at a northwest angle to it, and shot into the window of the bedroom where Chasity slept. The bullet came about 80 yards, through the bottom of the window, flew over the bed she was sleeping in and then lodged into a door frame on the other side of the bedroom.

The bullet hole is still there today, as is the bullet. "My mother wouldn't let the Sheriff's Department or the FBI or anybody else take the bullet out because she thought they would do something with it," Briggs Be said, standing in the bedroom, surrounded by pictures of his mother and father and great-grandfather, who first owned land in Franklin County and started passing it down through the generations. "It's still in here."

So is the pain. Charles, who was 5 when his father died, still lives in the house with that bullet and the family photos. He remembers his dad being taken away by his Uncle Perry after he took ill; he also recalls his mother's quiet faith, which bolstered his dad's activism.

"Dad was the theologian, but my mom was the holy one," said Charles Briggs, who today attends the Roxie First Baptist Church and often reads his Bible.

In his journal, Rev. Briggs continued to chronicle Klan activity for the rest of 1964. He stapled in an Oct. 7 news clipping with mug shots of Seale and Edwards, titled "Held in Torso Murders." He wrote about the Klan abduction of Burl Jones, 27, on June 21, out of the Meadville jail (although he didn't name him; the JFP found Jones and interviewed him in 2005). Much like the Dee-Moore case, the Klansmen took Jones into the woods and tied him to a tree, then "beat him unmerciful and left him for dead," Briggs wrote. "The young man came too and made his escape. He left Franklin County, Miss. (sic)"

Briggs then notes another attack on his homestead on Aug. 10, when a group of white men "shot two times at a light in his yard, broke the globe of the light but the light kept burning."

Under that entry, Briggs wrote, "No arrest was made in connection with any of those crimes, although each of them was reported to law officers of Franklin County, Miss."

Briggs died on Jan. 18, 1965, a week before his youngest son was born.

Seven days earlier, local district attorney Lenox Forman had dropped charges against James Ford Seale and Charles Marcus Edwards.

After Donna Ladd and photographer Kate Medley reported this story about Rev. Briggs' journal, and the original story about Thomas Moore's journey for justice, the journal was used as evidence, along with other reporting by this newspaper, in federal court. John Briggs Be was a witness in that trial, helping to convict James Ford Seale for the kidnapping of Charles Moore and Henry Dee. Seale later died in prison.

Previous Comments

- ID

- 80929

- Comment

- well written story. I see a gift membership to the NRA in your near future. ;-)

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-21T16:58:18-06:00

- ID

- 80930

- Comment

- Can you imagine how different this would have turned out if they didn't have the right to bear those arms? This is why it is soooo important for us to protect our rights.

- Author

- LawClerk

- Date

- 2007-03-21T17:24:37-06:00

- ID

- 80931

- Comment

- Nice work, Donna. You did right by your sources ; ).

- Author

- Ben G.

- Date

- 2007-03-21T20:13:28-06:00

- ID

- 80932

- Comment

- Thanks, Ben. ;-) It's remarkable to me, 'Fish, that I've become such a mouthpiece for the NRA. It's inadvertent, I promise. This is bigger than gun rights; this is about the right to be human and treated as a human. LawClerk, they didn't really have the right to bear those arms, any more than than they had the right to vote or to have equal schooling to whites, or anything else that stepped over the Jim Crow line. Remember that it appears that the Klan called a deputy and highway patrolman to go look for the guns they were supposedly stockpiling—according to the indictment, while Dee and Moore were near death at a farm waiting to be thrown into a river. I can only imagine what they would have done to Preacher Briggs if they had found guns. I wouldn't exactly call that the "right to bear arms," but I see your point. I will say that, ever since I studied Malcolm X and black nationalism in some detail while in graduate school, I've wanted to write about the hypocrisy in states like ours of white people who believe that have the absolute right to defend themselves with guns, but the minute a black person arms themselves for protection, it's a different ballgame. That's changed somewhat, but not all that much when it really comes down to it. It's more the hypocrisy than the guns I'm interested in, but I think there is a common ground here for folks who feel strongly about gun rights. It is vital to understand about our history (and I would argue our present if you stop to think about the hunted becoming the hunters in many instances) that black Mississippians were not *allowed* to defend themselves or their families. At least until they defied that prohibition and risked their lives to do it anyway. Might there be some sort of connection to the gun play we see today in our black communities? I don't know, but it's interesting to ponder. There really is a lot to think about here, I think. I will be doing more stories to push these issues even further. I've been wanting to do this for a long time. I appreciate all your comments and thoughtfulness. Cheers.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-21T22:51:56-06:00

- ID

- 80933

- Comment

- damn, for a second there I thought I was reading Thomas Sowell. ;-) He made the same points several years ago about how gun rights were selectively protected when different ethnic groups were involved in the South. Enjoy is the wrong word to use but I can think of no other word to use right now than to say I enjoyed reading the piece.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-21T22:58:52-06:00

- ID

- 80934

- Comment

- Time to go to bed. Good night Ray Good night Emily Good night Itodd Good night Lady Havoc Good night Brian Good night Donna Ellen Good night Pike Boy.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-21T23:00:47-06:00

- ID

- 80935

- Comment

- Thanks, 'Fish. It's OK that you "enjoyed" the piece. Really. ;-) I'm not surprised that Sowell made the same points (although I'm continually amazed at your attempts to place me on one end of some binary spectrum. Barking up the wrong tree there). This isn't a partisan issue, or even necessarily about gun rights. It's about equality. My point is that you don't have to be a supporter of guns in any fashion to understand why it was so horrifying that blacks weren't even allowed the right to defend themselves in their families *in the same way* as whites until they reached out and took that right for themselves. But at a heavy cost. And the fact that so many whites have so long misunderstood Malcolm is a key point, too. In grad school, I analyzed all of his speeches and the media coverage of them in papers like the New York Times. His message was that of *self-defense*—even as he worked to help scare white supremacists, especially when he was talking to white audiences or to (white) media. Reading about the Deacons' ploys in South Mississippi (I LOVE the fake minutes book; snirk) reminded me of Malcolmn's brilliant use of rhetoric to scare the bejeezus out of white folks. Looking back, you can hardly blame him, especially when it comes to Mississippi. It wasn't like nonviolence was working here; white resistance in our state was too violent and, perhaps, our compassion pathways were quite tuned, yet. (A lingering problem.) Whatever it was, the worst race violence happened in our state, and that's a fact that it's time to face. Desperate times called for desperate measures. It's unfortunate that the courage that so many blacks showed in defending their families and other blacks hasn't exactly made it into our history books. It is adding insult to injury that not only did whites treat blacks so horrendously then, but now want to take most credit for the Movement and refuse to ackowledge the legacies of the horrors of white supremacy. Do we ever learn?

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-21T23:10:27-06:00

- ID

- 80936

- Comment

- It's Donner-Kay, I have you know. And don't EVER call me that. Night, night.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-21T23:11:14-06:00

- ID

- 80937

- Comment

- Donna, point well taken! I guess I'm saying that as humans, they had the right, even though MS didn't want them to have them... exactly so they wouldn't be able to fight back! "Laws that forbid the carrying of arms. . . disarm only those who are neither inclined nor determined to commit crimes. . . Such laws make things worse for the assaulted and better for the assailants; they serve rather to encourage than to prevent homicides, for an unarmed man may be attacked with greater confidence than an armed man." -- Jefferson's "Commonplace Book," 1774-1776, quoting from On Crimes and Punishment, by criminologist Cesare Beccaria, 1764

- Author

- LawClerk

- Date

- 2007-03-22T07:05:41-06:00

- ID

- 80938

- Comment

- Here are some additional articles I found online about the use of control policies to keep Blacks from protecting themselves. gun control gun control

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T08:22:31-06:00

- ID

- 80939

- Comment

- Great column with great detail, history and story lines. Mississippi was a horrible place, and I don't know how any reasonable and decent person can deny it, or support that history and legacy by keeping that rebel flag as the state flag or hold steadfastly to the old ways of Mississippi, except they like, preter and intend on keeping a symbol of that ugly past. I'm convinced that voting to keep that flag is a blatant message by whites to blacks that we don't give a damn what happened to black folks, and that what my ancestors did, I condone, acquiesce to, and protect them for it, at any rate and cost to you that I can. I only wish the supporters were still bold and dumb enough to admit it. Like the rest of the south and elsewhere, we wear the mask, these days. I don't buy one word of that bullcrap about slavery and Jim Crow being the way it was back then and everybody had to accept it. Every white person knew it was wrong, and nearly every white person supported it by deeds or inaction. And to have the nerve to call us VIOLENT when the world has never seen anyone more inhumane and violent than the white man. I'm glad that some blacks realized the only way to stop evil was to shoot and kill it. The Klan was and is fecal trash just as any supporter of it is. Frankly, I'm a little bit surprised that dumb, poor white boys would join it willy nilly without even understanding the implications of what they were to accomplish. Howewer, I'm not suprised that white business men, merchants, police officers and the so-called white intellegentsia were members or supporters. They, by and large, are our real racists, and they used poor whites to do their dirty works. Telling the truth about our past is therapuetic, and it will set us all free to move forward together. Hiding and running from the truth are the arsenal of a coward who don't want freedom and justice.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T08:51:53-06:00

- ID

- 80940

- Comment

- Ray, you make a good point. I have a problem with a lot of the journalism that goes out about the Klan because it seems to let the rest of white society from that era off the hook. The Klan, folks, was the terrorist wing—the hicks doing the dirty work, you could call it—of a statewide conspiracy to keep black people down. Until we understand that about our history, we are stuck and will continue to chase our tails. That's why I believe it's so important that Mississippians tell our own stories, with unabashed honesty and in great detail. Catching an old Klansman cowering from cameras on his doorstep is one thing; sitting down and talking to him about the conditions that led him to do such a thing is another. Also, it is so vital for the families of victims (and Preacher Briggs was certainly a victim of Jim Crow, regardless of how he actually died, even if he did die standing up; bless his soul) that these stories be told, over and over again. This is why it infuriates me to hear journalists and public figures proclaim that "this is the last case." Nope. Believe me, these stories are going to be told. We don't have a home office in Virginia, or D.C. or somewhere, telling *us* to move on. May Preacher and Mrs. Briggs rest in peace.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:23:31-06:00

- ID

- 80941

- Comment

- And to have the nerve to call us VIOLENT when the world has never seen anyone more inhumane and violent than the white man. Speak, Ray. White people still have a lot of soul-searching to do. It's damn cynical to go around whining about crime in the black community that our policies created.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:24:52-06:00

- ID

- 80942

- Comment

- "when the world has never seen anyone more inhumane and violent than the white man." oh really?

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:28:01-06:00

- ID

- 80943

- Comment

- Well, King, we can debate that issue, but I know of no one tantamount or paramount in modern history. I probably should have said the modern world of the last half century or so. Prove me wrong if you can.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:39:54-06:00

- ID

- 80944

- Comment

- Ray: Please tell me you are not that ignorant. Rwanda? Slavery in the Sudan? Yes, there is slavery there. How many mass murders have occurred in Africa? Then there was the killing fields in Cambodia. Those were Orientals, not Whites by the way. It was pretty systematic too. Then there were the killings done when the communists came to power in SE Asia and the "re-education" camps. Remember Chairman Mao and his purges and cultural revolutions? Ah yes, then there is the humane treatment by Arabs of others, including Arabs who are not of their own sect. THen there was the Armenian genocide by the Turks, who were pretty brutal themselves. Do you really want me to keep going? If I were you, I'd be begging for that sentence to be deleted.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:44:21-06:00

- ID

- 80945

- Comment

- It would also be intriguing to substitute "the U.S." for "world" and see what comes up. Of course, I think an argument about "most violent" would ultimately miss the point—which is that white Americans treated black people like chattel to be sold, hunted and killed until very recently. At that point, white America started incarcerating and blaming black people for all of our violence, and tried to make it seem as they created the violence in America problem. That is flat wrong, and it's time we acknowledge it.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:46:06-06:00

- ID

- 80946

- Comment

- Kingfish, why not be respectful? There are very good answers to your questions, and you're making yourself look like a jerk the way you're framing this. Do you truly believe that the white man has had NOTHING to do with the violence in Africa? Come on, dude. You can do better than that. That's up there with your old comments about the playing field being level between whites and blacks after the Civil War. Stop being blinded by your whiteness. I am white, and I don 't hate myself because of it—but I also don't fool myself into thinking that my ancestors are some of the most violent people who have walked this planet. If we want to solve the problems of today, we will face that—just like they had to in Nazi Germany.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:52:09-06:00

- ID

- 80947

- Comment

- Or, I should say "post-Nazi Germany."

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:52:29-06:00

- ID

- 80948

- Comment

- You look at the problems between ethnic groups in other parts of the world and ours seem pretty mild. Not excusing for one second slavery, which was evil and immoral, and the Jim Crow laws and their ilk. However, when you compare it to the genocides, mass murders, final solutions, killing fields, re-education camps, cultural revolutions, Mid East, ours have seemed pretty mild. Yes, there was a civil war but I think it is a testament to our policital system and culture that we have dealt with these problems and issues without falling into the deadly abyss that has trapped so many other parts of the world. For example, were there civil rights problems? Yes there were without question and they were widespread. However, they were also dealt with rather successfully by our constitutional system. Compare that to other parts of the world where ethnic conflict too often is resolved at the point of a gun. After all of our problems me and Ray can go eat lunch together or have a drink and no one thinks twice about it despite the friction that occurs in our society. If me and Ray were living in Palestine, Iraq, Japan, or somewhere else, we would be ostracized or killed for doing so if we belonged to different ethnic groups.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:53:53-06:00

- ID

- 80949

- Comment

- Just saw your post. I have not said for one second the past should not be confronted and dealt with. I am taking issue with Ray's one sentence about the White man being the most inhumane and violent than the white man. Slavery is still being practiced by Blacks in Africa. The white man has nothing to do with that. In fact, one of your heros, Nat Hentoff has strongly criticized the Black Civil Rights leadership here for not condemning it. I fail to see how you can blame the White man for the genocide in Rwanda. In fact, while we are talking about Africa, are you going to acknowledge how many Black tribes in Africa enriched themselves selling their fellow Blacks to slave traders? My main point however is that EVERY ethnic group is guilty of genocide, mass murder, and inhumane, systematic treatment of their fellow men or other groups. There is no race worse than any other.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T09:58:38-06:00

- ID

- 80950

- Comment

- I take it you think what you set forth above is worse that what happened in Europe, here and elsewhere by your forerunners to blacks and many other non-whites throughout the world. I'd have to do an in depth study of the situation, and read many more scholary and honest reports comparing the atrocities before I would ever accept your un-proved conclusion. You know that I'm not even close to being ignorant, and know I know, to some degree, about all the atrocities you mentioned. Thus far, you haven't proven anything to me about my comments that you take issue with other than that you are still defensive about what many would call the undeniable facts of the modern past. That's fine with me, as I make no pretense of my hurt and anger about the past wrongs to us. I'm going to study this issue before making that comment again. If I'm right I won't have any hesitation or issue about repeating it.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:02:32-06:00

- ID

- 80951

- Comment

- I'm not defensive nor have I denied anything at all. All I have done is taken issue with your "worst" comment. Prove? I have written pretty well established facts. I didn't make up the Killing fields. Have you bothered to look at the genocide practiced over in Asia? Go look up how the Turks ran their empire in the 20th century. Look up Armenia while you are at it. Just do some research on Mao. Then there is the Sudan. Rwanda. Pretty well known stuff there. My "unproved conclusion" is that every group has participated in atrocities, genocides, and practices such as slavery that were pure evil. There is no group worse than the other. The Asian communists who took power and then butchered their own people were every bit as systematic as Whitey. However, feel free to do research on the subject. ;-)

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:09:34-06:00

- ID

- 80952

- Comment

- "I take it you think what you set forth above is worse that what happened in Europe, here and elsewhere by your forerunners to blacks and many other non-whites throughout the world" Do I think that the killling fields and resulting slavery in cambodia were worse? yes I do. Was there a wholesale systematic slaughter of Blacks in this country? No there was not. Did whites come in in this country and butcher tens of thousands or more like in Armenia? Was there a rape of Nanking in this country committed by Whites against Blacks. ALL I am doing is placing things in context, not excusing anything from the past. I have not excused one sin or cime. Just saying that there was worse or more out there.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:12:58-06:00

- ID

- 80953

- Comment

- King, what you're doing is jumping on someone else's subjective opinion about "worst"—and, yes, one can make a very good case for it, although you would never listen to it—and trying to change the subject away from the horrors by our ancestors that has created the mess we have today. Why not deal with what's in front of us? Also, you're just a dumbass if you try to point to the violence of Africa without taking into account the efforts of white colonization, mining (in every possible form) and the slave trade. That is the white bigot's favorite excuse, and it's ignorant, probably because our history lessons are so whitewashed in this country. Be bigger, and smarter, than that.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:20:39-06:00

- ID

- 80954

- Comment

- However, feel free to do research on the subject. ;-) Kingfish, are you dense enough to believe that the people you're talking to don't know anything about the Killing Fields or the atrocities in Africa? The problem here is that you are parrotting the defensive white version in order to prove Ray wrong. In so doing, you're making yourself look very uneducated about the real world and the factors that have created conditions of violence. In so doing, you are proving my original point. Thank you.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:22:58-06:00

- ID

- 80955

- Comment

- Well, now. I never excused any other group or said other groups were free of similar indiscretions. I said no one has a history more violent than the white man. I'm still not convinced I'm wrong. And I'not accepting your conclusion just because you say otherwise, just as I don't expect you to accept mines. My money is on the fact that neither of us know the real answer to that question at this point. I could be wrong and will accept tit when I see otherwise. I don't know necessarily that one group is better or worse than another, but I know as far as single-minded, world-wide, imperialistic hostilities, encroachment, violence, and theft toward others; King, your forerunners stand alone, at the top. Can you deny it?

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:25:40-06:00

- ID

- 80956

- Comment

- My apology to anyone I offended other than King.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:28:23-06:00

- ID

- 80957

- Comment

- Ray's right, Kingfish. You just jumped into the binary well once again. What's curious is why it would offend you so that a black man would think that there is no history more violent than the white man's. It's a waste of time and energy to try to argue that point by trotting out black atrocities. That's Jim Giles' and the Citizen's Council's modus operandi. Why not choose to be part of the solution instead of repeating tired white protestations?

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:29:55-06:00

- ID

- 80958

- Comment

- You are correct. I won't listen to it when I know history well enough to objectively disagree with it. I have not whitewashed anything. I have not denied anything. Find where I have? I have not said there were no horrors associated with our ancestors. However, I am taking issue with a "worst" label and I think it is more than worthy of criticism. I am dealing with what is in front of me, which was the above quote. I found it bigoted to say the least and a smear upon a whole race of people. I found it very offensive because I know for a fact it is not true. As for Africa, I am aware of the problems contributed by colonialism. However, slavery has been practiced by all ethnic groups. All of them. The Sudanese didn't practice slavery because of the White man. Considering they are next to Egypt, I can assure you that they were already very familiar with the concept before the first European appeared. They practice slavery today and that is NOT the White man's fault despite your protestations to the contrary. I'd like for you to explain Rwanda being the White man's fault to me as well. If you want to argue we should've intervened, you have a point. However, White people did not cause that genocide and did not participate in that. Why not deal with what is in front of us? I"m all for it. What I said about our constitutional system and how we have been resolving our problems is how we have been dealing with it. I am all for open and honest discussions on race.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:30:52-06:00

- ID

- 80959

- Comment

- as for getting offended, I get just as offended when someone says that about the White race as Ray would if someone said all Blacks are stupid and violent. Thing is, I like Ray and read his posts on here and respect his opinion so I was a little disappointed to see him write that statement.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:36:24-06:00

- ID

- 80960

- Comment

- ... as long as they don't make white folks too uncomfortable, eh, 'Fish? You're flapping on the shore here, friend. You know enough history to make whitewashed arguments (I assume inadvertently). So did the Citizens' Council. Do you realize that you often repeat, nearly word for word, much of their propaganda on these types of issues? Again, I don't think you're doing it on purpose, or that you're a bigot. I think you've drunk the Koolaid and don't like people to criticize white folks without giving equal time to people of other races.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:37:23-06:00

- ID

- 80961

- Comment

- You're whitewashing King because you desire to jump from the early 1600's to the 1960's when the white courts finally agreed to honor the constituion. You can't handle what happened in the interim. Lots of folks can't.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:39:20-06:00

- ID

- 80962

- Comment

- I know this country didn't have a constitution that far back. So don't bore me with that correction.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:42:19-06:00

- ID

- 80963

- Comment

- Not at all. If ray don't say worst or most, we are not having this discussion. If it was about the sins that whites committed in the past and today, I have no problems with that and doesn't offend me one bit. You are reading a little bit too much into what I am saying. The only thing I am taking issue with is that worst label. I haven't read CC stuff so I have no idea what they say or write. Ray: as for your take on history, another theory, proposed by Paul Kennedy (The Rise and Fall of the Great Empires) is that Europe was composed of several nations which were all competing with each other. Islam and Chinese civilizations had become static empires with little competition or innovation and thus stagnated. Each went through their aggressive growth phases, just at different times (which is what happened to Japan and Germany to some degree). If you were living in 900 AD you probably would've said the same about Arabs if living in N Africa or Europe and someone would've pointed out how bad the Romans were.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:44:10-06:00

- ID

- 80964

- Comment

- get just as offended when someone says that about the White race as Ray would if someone said all Blacks are stupid and violent. Oooo, 'Fish, nice attempt at a bait and switch. Ray did not say that all whites are stupid, or violent. This is a false dilemma (or one of those other fallacies that I forget the name of). What he opined was that there are no races with a more violent history than white people. I hate to tell you this, but it is impossible for you to prove that particular statement wrong. It's curious that you're trying so hard. Quit while you're not as far behind.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:45:39-06:00

- ID

- 80965

- Comment

- "You're whitewashing King because you desire to jump from the early 1600's to the 1960's when the white courts finally agreed to honor the constituion. You can't handle what happened in the interim. Lots of folks can't." Haven't whitewashed at all. Ray. In fact, I've acknowledged it. Look familiar: "Not excusing for one second slavery, which was evil and immoral, and the Jim Crow laws and their ilk. "

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:46:11-06:00

- ID

- 80966

- Comment

- My main point however is that EVERY ethnic group is guilty of genocide, mass murder, and inhumane, systematic treatment of their fellow men or other groups. There is no race worse than any other. Unfortunately, if you buy into statements like "white men" are the "most" inhumane or violent EVAR, then you are ignoring the common failings of "man" throughout history. We (humans) are the only beings on Earth that have gone out of the way to find numerous ways to maim and kill our fellow men. Societies from every shade of color have searched for ways to torture and kill those who were not from their sect or culture. I think humans are basically good. But, humans have shown they can be as evil as the devil on earth when not kept in check. American men have a bad record of abusing women and it took years for women to vote or gain an equal footing. The Suffrage Movement eventually prevailed, and started the ground work for women to be equal in this country. Some say it is still not equal. It certainly isn't perfect. But, should we go on record as saying American men are the worst EVAR when it comes to womens rights and abuse? Trying to determine who are the "worst" abusers in history by race, sex or creed is a pissing contest I wouldn't want to get into.

- Author

- pikersam

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:49:10-06:00

- ID

- 80967

- Comment

- I know he didn't. I was merely criticizing making a general statement he made about a Race by pointing out what some idiots say about his race and how he would find it offensive if it were made.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:49:59-06:00

- ID

- 80968

- Comment

- that is the point I am trying to make Piker. Thank you for making it more eloquently for me.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:51:39-06:00

- ID

- 80969

- Comment

- ... however, I assume, Pike, that you are not offended that a black man who grew up during Jim Crow would think that, right? That's the point. This 'Fish's p!ssing contest, and it's stupid. Sadly, it's also familiar to those of us who have studied intimately the history of white supremacy in America and Mississippi. It's the same arguments. Also, note that it pulls the discussion away from what happened right here on the home front that contributes to our problems of today. My suggestion is to ignore 'Fish's taunts and stay on topic going forward.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:51:56-06:00

- ID

- 80970

- Comment

- Pike, do you think that suffrage prevailed because women whitewashed their abuse by men by going around saying that, well, women act just as badly toward men? No.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:52:54-06:00

- ID

- 80971

- Comment

- I was merely criticizing making a general statement he made about a Race by pointing out what some idiots say about his race and how he would find it offensive if it were made. But, it didn't work because you didn't use a parallel argument, 'Fish. You just look like you're trying to change the subject. Go back into the water.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:53:54-06:00

- ID

- 80972

- Comment

- actually I can understand why someone who grew up during that would think that. Just like an old man who fought the Japanese in WWII and might have seen Kamikazes attacking his ship or buddies blown up by them might get offended over Kamikaze's name ( I know I am assuming alot about your caller here).

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:54:55-06:00

- ID

- 80973

- Comment

- for the record, there have been no taunts. I have posted nothing out of anger or with any malicious intent.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:56:21-06:00

- ID

- 80974

- Comment

- King, I take it you have an unstated point you're trying to make? We're not even debating any more. I'm merely listening now, hopeful you have a point of some kind. You haven't proven anything at all, except you don't like the statement. I don't like the statement either, and wish you had information it's totally false. I intend to discuss it with a real historian though. Cheers, my brother!

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:56:31-06:00

- ID

- 80975

- Comment

- However, (just saw your last post) if someone were to say that American men were the worst ever to women, yes I would take exception to that. All I would have to do is point to how women are treated under Muslim regimes in general.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T10:57:44-06:00

- ID

- 80976

- Comment

- King is engaged in pandering self-esteem and confidence regardless of horrific facts while simultaneously trying to inoculate himself and others from self-evaluation and blame. I could write more but it won't do any good. Don't worry, my comrades, King's tirade provides not contestability here whatsoever. I can barely respond to him for laughing so hard.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T11:11:27-06:00

- ID

- 80977

- Comment

- No self esteem problems here. I'm just dealing with ignorance and some good old bigotry. Only reason you are laughing so hard is you don't know enough about world history or else you would see why I am arguing with you. I remember Ladd slamming a poster for saying how violent Muslims were. Never mind there is a creed and a long history to back up such a statement. However, let a bigoted statement be made about White people and that is perfectly ok. Double standards. got it.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T11:31:34-06:00

- ID

- 80978

- Comment

- King, that was not a bigoted statement. That was merely a comment on U.S and World History as I view it, and a comparison of claims about blacks and white. I'm likely to not even accept your version of tainted or concocted history. The claim that blacks were violent in any real or calculatable way toward whites during Slavery and Jim Crow is a total lie, just as to claim white men weren't monumentally and peerlessly violent and inhumane to blacks during those periods is a lie. History my ass, you don't really won't to talk about the history of your forerunners, which explains your changing the subject matter and blaming the messenger instead of the assailants discussed in that piece. Unless some Klansmen or truly ignorant people are reading alone, you're not fooling anyone. Where I grew up we don't throw rocks and run. What else you got!

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T11:49:16-06:00

- ID

- 80979

- Comment

- Ladd, of course I can see where a black man who lived through some of Americas darker days could think that "whites" are the worst humans EVAR! However, that doesn't make it true. Obviously, a majority of white folks finally said enough too. So far, it is still not enough of us; but, it is a snowball going downhill. We just need to increase the grade. And, sometime Ray likes to bring it hard to get that ball rolling. That's Ray. And, you have to expose the bad to bring forth the good as you asked in regards to the women's movement. I was not saying that they have to shrink to a lower level to move forward. It's those the hold themselves to a higher standard that prevail in the long run. MLKjr, Martin Luther, and Gandhi come to mind. Even Rosie the Riveter was a symbol of a higher standard - a higher ideal. No, I agree with you on that point. But, I don't want to perpetuate that the "white man" is the most evil human being nor more than I want to hear some white guy say blacks are the worst thing to happen to planet earth. Ray likes to use absolute extremes when he tries to make a point. In particular, republicans and whites are the scourge of all of the worlds ills at times to Ray. But, Ray is smart enough to know that the logic is not there to support his absolute "truths" about either. I know this is true because many times Ray finds agreement with those across the aisle, both church and political. I like Ray "the defense attorney" over Ray "the late night public access wacko" he sometimes portrays. ;-)

- Author

- pikersam

- Date

- 2007-03-22T11:57:53-06:00

- ID

- 80980

- Comment

- um, Ray, I think you missed something. I have not denied anything done in the past. period. Got it? That means slavery. Jim Crow. The Klan. Race codes. I liked reading the article and think it is a story that needs to be told more. I am against gun control and those stories are great reasons why I am against it. I also did not say one word against Blacks. What I said was that you were making a statement I thought was pretty ignorant and bigoted and said it would be the equivelent of what some white racist redneck would say about Black people and gave an example of that. I think after law school and practicing law you understand that kind of argument. However, if you want to say I was saying something against Blacks go ahead even though you know I did not do so. We can talk about the history of my forerunners all day. We can even start a seperate thread about it. The only thing I had was the worst tag. Especially when I look at the history of Islam, Orientals, the Aztecs, and other groups. That was it. However, you and others seem to think I was trying to deny white history when I expressly did not do so.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T11:59:56-06:00

- ID

- 80981

- Comment

- But, I don't want to perpetuate that the "white man" is the most evil human being nor more than I want to hear some white guy say blacks are the worst thing to happen to planet earth. Pike, are you paying attention to what Ray said: He said "the world has never seen anyone more inhumane and violent than the white man." Read his words carefully and consider why this bothers you so. If you pay attention to the words, he is saying that non-whites are not (or have not been) *more* violent than whites, which is what is presented and accepted every. single. day. in our country. It's conventional wisdom, without consideration of why the hunted have become the hunters, in too many instances. Why doesn't Ray get to say that without white guys jumping him, considering that as a black man he has to listen to proclamations about his community being the most violent constantly? Kingfish's response was predictable, and hackneyed, and I applaud Ray for drawing it out so it can be discussed. (He is smart if you hadn't noticed.) Thank about his statement, and the reaction to it, carefully.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T12:53:55-06:00

- ID

- 80982

- Comment

- Oh, and notice how Kingfish just called Ray "ignorant and bigoted" for that statement.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T12:56:35-06:00

- ID

- 80983

- Comment

- Pike that'a a decent classification of what I try to do here. Believe it or not, I usually make an effort to be correct or at least arguably correct. I didn't say and didn't mean to say white folks are the most evil people on earth. I said what I said in a certain context and wasn't changing it to make King feel alright. Yes, I know some people relish a chance to attack me. I recognize that I can be wrong. I not against change or correction, and much of what I try to do here is encourage others to change. I have said numerous time that I have met wonderful people of all races and some bad ones of all races too. As far as being bigoted or making comments that are bigoted; King, I bet a fair observer would find my comments less offensive than yours if they viewed all comments made by us from beginning to end of the time we started posing with the JFP. I admit I don't write to please southerners and Mississippians. I know too well what most would rather hear, but they will rarely hear it from me. I prefer to take them where they don't want to go. Pike and many more are living testaments that there is a plan to my method. At first they hate me, then, they learn I'm neither racist, hateful, dumb, clueless, et al. Certainly not scared. We have done Donna's wonderful piece a disservice by going off on an inconsequential tangent.

- Author

- Ray Carter

- Date

- 2007-03-22T12:57:24-06:00

- ID

- 80984

- Comment

- It's OK, Ray. I think there's something appropriate, if sad, that my piece about black people not being "allowed" to defend themselves ended up with reactionary, if incorrect, readings of what you said. Dialogue between (and among) races isn't supposed to be easy or comfortable. Like you, I do not exist to make white men, or anyone else, comfortable. I'm here to tell the truth. And you are right in your assertion that set 'Fish off: Other races are not more, nor have been, more violent than white people. We white folks need to get off our high horses about it and be part of the solution instead of fingerpointing and blaming everyone but our frackin' selves. Honesty. Real history. Solutions. That's why I wrote this story. The road there will be bumpy, but stay on it, all.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T13:03:41-06:00

- ID

- 80985

- Comment

- The only thing i had a problem with was this: "And to have the nerve to call us VIOLENT when the world has never seen anyone more inhumane and violent than the white man." I agreed with everything he said in that post before and after. I'm going to slam someone on here for making sweeping generalizations about ethnic groups every time whether here or on other sites. I challenged him by showing that that was not true about white people that all groups have done things just as evil as the others have done. That is not whitewashing history despite how you twist it Ms. Ladd. You just don't like being challenged on some issues. You really want to defend saying that there has never been anything more inhumane or evil than the white man? You really want to defend that one? Once again, you ignore my saying that he has done plenty of evil. Slavery (all groups have practiced it although the version practiced here was worse than the Roman version in some ways). Final Solution. More "minor" evilis such as Jim Crow. I don't blame the Blacks at all back then for not taking that garbage and defending themselves. I agree with most of what Ray wrote. I liked the story and think it needs to be told. I even went so far as to post a link to it on other sites. I even see where Ray is coming from. The only thing I have a problem with is the statement about White people in general and even then I am not denying anything, just putting in context and saying I thought it was bigoted. Now crow about how this argument is over, how I am defensive, how binary my thinking is, how I mean well and don't get it. I do react quickly, not because I am defensive but because I thought the statement about white people was either going too far or ignorant. Maybe it exposes some resentment still in Ray. I know he is not an ignorant person so I was a little surprised by it.

- Author

- Kingfish

- Date

- 2007-03-22T13:32:43-06:00

- ID

- 80986

- Comment

- You've made no coherent argument about what's wrong with that statement, Kingfish. You've twisted it backward and forward to try to make it say something it didn't. You've called Ray ignorant and bigoted. You've tried to compare the Rwanda situation to the U.S. (instead of, say, Nazi German). You're weaved, and dodged, and bellowed, and you have said nothing to back up the names you called Ray because of that one simple statement. I'm with him: With the history I know well, in this country and elsewhere, it is appalling that white folks state wih superiority that other races are more violent than our own. That in no way negates the violence by other races; what it does is take people with my skin color off some superiod pedastal they have put themselves on. When we can do that with any kind of consistency, we might, just might, be able to work together to do something about the violence in this country and other countries. Ray has said nothing ignorant, 'Fish. You just refuse to actually ackowledge what he said, probably because it's too painful. Why, I don't know. White people love to say that we're not responsible for what our ancestors did—but then turn around and act like they're being blamed when once tries to talk about what their/our ancestors did. I don't have that sickness. I know *I* didn't do it; I also have no problem admitting what others did, on the road to understanding the legacy of it, and fixing it. It's a liberating place to be. You should visit it more often.

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T13:39:00-06:00

- ID

- 80987

- Comment

- And 'Fish, I *love* being challenged. That's when I'm at my best. Or hadn't you noticed. ;-P

- Author

- DonnaLadd

- Date

- 2007-03-22T13:39:42-06:00

- ID

- 80988

- Comment