It was like a reverse funeral procession. We were the third in a line of about five white vans, driving down the gravel road that led past a double set of mechanized cyclone fence gates topped with barbed wire to the one-story brick building that houses Mississippi's death chamber. When I first started representing death-sentenced prisoners, all the prisoners on Mississippi's death row lived here. The simple plastic bucket that still hangs from the outermost guard tower brought back memories of my frequent visits to Unit 17. We would park my non-air conditioned, 1963 Buick Special Edition and drop all keys in the bucket before the first of the fence gates would creak open and allow us into the yard.

But this day, May 21, 2008, only one prisoner lived at Unit 17: Earl Wesley Berry. When the Mississippi Department of Corrections built the new maximum security Unit 32 in the early 1990s, death row was moved to one of its six wings. Unit 17's small brick structure was retained for only one purposeto be the "death house."

A week before, Berry had been moved here and kept under constant surveillance pending his execution for the 1987 murder of Mary Bounds. As he told us during our attorney-client visit earlier that afternoon, the guards would come by several times an hour, calling his name. Earl didn't seem to know that this was the suicide watch, making sure that he stayed alive long enough for the state of Mississippi to kill him.

'Like He Was Dumb'

Earl Berry had been considered "slow" his whole life. He didn't walk until he was 2, he nursed until he was 4, and he didn't begin talking until he was 5. (He also couldn't tie his own shoes until he was 7 or 8, but then, neither could I). His brother carried him when Earl was 5, because he still tottered when he walked.

Earl wasn't just a slow developerhis mental difficulties continued into his school years. A teacher at one of Earl's schools told us that he "appeared withdrawn most of the time. He tried to fit in, but he had trouble doing that." A classmate noted that Earl "did not seem to mature like other young people did." Other observers said that Earl "seemed to prefer to play with younger children rather than with children his own age" and was a "child in a grown-up's body."

Earl failed first and third grades. He was "transferred," not promoted, from second to third grade. After repeating third grade, he was "transferred" to fourth grade, and then "transferred" again to fifth grade. On an achievement test he took when he was in fourth grade, Earl scored in the third percentile in reading (1st grade equivalent), 11th percentile in mathematics (4th grade equivalent), and eighth percentile in language (2nd grade equivalent).

As we all know, mental problems like Earl's can become fodder for classmates' ridicule. As James Berry, Earl's brother, told us, "Other people treated Earl like he was dumb and teased him because of his speech impediment and because he had so much trouble with reading and writing."

At age 13, years before the death of Mary Bounds, Earl was given an intelligence test at school; his IQ score was 72, which is within the scientific range for mental retardation. Earl dropped out of school when he was in 7th gradeat age 15.

After leaving school, Earl lived with his grandmother. He never learned to care for himself. As James recalls, Earl did not cook, clean, iron or do laundry. Although all the Berry children were assigned such chores, Earl was unable to do them and, thus, never learned the necessary motor skills to accomplish these simple tasks. He had to be told when to bathe and change his clothes. It took Earl three attempts to get a driver's license, and even then he had to take the oral examination because he couldn't read the written test.

Earl got into trouble early in life, and was imprisoned in 1981, before Mrs. Bounds' killing. In that previous incarceration, the prison's medical records show that he was diagnosed as mentally retarded. But Earl wasn't taught any skills or trades in prison. Like most in Mississippi's criminally negligent penal system, Earl was merely housed, having his mind formed by scores of antisocial attitudes, behaviors and desires.

After the unspeakable horror of Mrs. Bounds' murder, as he awaited trial in jail, Earl was tested again, by a mental-health professional who mostly tested defendants for the prosecution. He scored Earl's IQ in the low 80s, above the line for mental retardation, but noted signs of brain damage, finding indications of dysfunction in the left side of the brainmanifesting itself in problems with judgment and abstract thinking.

'In a Man's Body'

For reasons that aren't clear, the pre-trial testing Earl received was not comprehensive. The higher IQ results were inconsistent with the score of 72 in junior high school and later scores of 68, 73 and 74. An 83 IQ didn't fit Earl's history as "a child's mind in a man's body." But in essence, the pre-trial test led Berry's trial lawyers astray. They did not present Earl's retardation to the two juries which both sentenced him to death (the case was sent back for re-sentencing because of improper jury instructions in the first trial).

Earl's second set of lawyers was supposed to be led by a specialist in constitutional law and post-conviction procedure. After years of having execution dates blocked by the federal courts because prisoners had no counsel, in 1999 the Mississippi Supreme Court recognized in the Henry Curtis Jackson case that defendants facing execution must be given appointed counsel with expertise in post-conviction appeals. In 2002, the Legislature responded to the Jackson case by creating the Mississippi State Office of Post-Conviction Counsel.

But the state office's first director, Jack Williams (the lawyer who won the Jackson case), had been, it seemed to many of us, pushed out of office. He had been assigned 16 cases right off the bat, and when he resisted pressure to rush the preparation of those appeals, he was ousted. The replacement director, Robert Ryan, had scant experience in post-conviction appeals, but he got the message: Move cases quickly, no matter what, no complaining. A series of appeals were quickly filedand just as quickly rejected by the Court, which seemed genuinely surprised at the haphazard work product that the state office threw together.

But the attorney general saw an opportunity and moved to take advantage of it. The state filed motions to remove private appointed counsel from death-penalty appeals in the state courts. Currying favor, the MSOPCC itself objected to anyone other than the director being appointed and compensated in death-penalty post-conviction cases. Although both the attorney general and MSOPCC made Orwellian noises about seeking "quality representation" for prisoners, the reality was that lawyers who had actually won death-penalty appeals were being replaced by the inexperienced director. By the time Berry's appeals were being prepared, the MSOPCC had taken over 24 out of 27 capital post-conviction cases. Private counsel were only allowed to represent death-sentenced prisoners on post-conviction review if they agreed to waive any payment and proceed pro bono.

In October 2007, as Earl's case was winding through its last appeals, Ryan, who was about to resign, had finally seen the error of his ways. He gave a sworn statement that Berry's appeal was filed by an attorney who "had not had an adequate opportunity to investigate and present all of the claims," and that the cases handled by his office "for all practical purposes had had little done on them by (the attorneys in the office) and desperately needed additional investigation and supplemental petitions."

A supplemental petition was filed in Earl Berry's case, but while it discussed mental retardation, it did not have a sworn statement from a mental health professional giving an expert opinion that Berry was retarded. This simple requirement was all that the Mississippi Supreme Court needed to grant a hearing on mental retardation. The MSOPCC provided no expert affidavit for Earl's case until August 2004, after the Mississippi Supreme Court had already ruled against Berry on his first post-conviction appeal. And this affidavit was not from a mental health professional, but from an Australian political scientist.

Of Counsel

In October 2007, David Voisin and I were asked to help with the case. David is a quiet, brilliant and effective Yale Law School graduate who has spent his entire legal career representing death-sentenced prisoners. He was a law clerk in 1992 when I was director of the Mississippi Capital Defense Resource Center, a non-profit organization that handled death-penalty appeals. Justin Matheny, an associate at Phelps Dunbar, prepared the groundwork for the lethal-injection challenge and continued to monitor developments on that front nationwide.

My paralegal, Michael Richmond, kept the logistics of our strike force running smoothly and without stress.

Jamie Priest, a talented young attorney who read about the case in the newspaper, soon joined us. His rapid research and clear writing soon made him a "go-to" member of the team. In January 2008, Glenn Swartzfager was appointed to begin a new day at the State Office of Post-Conviction Counsel, replacing Ryan as the new director. Glenn grew up hearing his grandfather tell stories of fighting death-penalty cases, and he carries that family spirit forward in its third generation. Van Williams, who suffered through the previous regime at the MSOPCC, maintained connections with the Berry family.

We succeeded in winning a last-minute stayliterally 17 minutes before Earl's executionin October 2007, but that stay depended on the U.S. Supreme Court's consideration of the Baze v. Rees case on lethal injection in Kentucky.

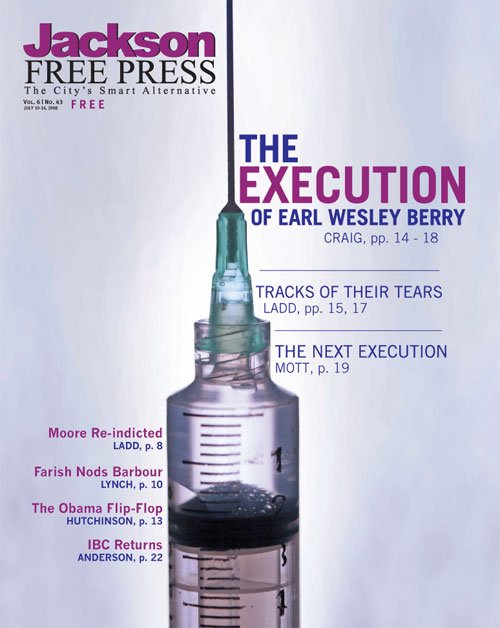

On April 16, the Supreme Court affirmed Kentucky's procedure, but in a very fact specific opinion that left open a lot of questions. For example, the Mississippi protocol uses the same three drugs as Kentucky, but uses a lower dose of the first drugthe anesthesia that is critical to whether the second two drugs cause excruciating pain. A lower dose of anesthesia was one of the factors in Angel Diaz's botched 2006 execution in Florida, which caused then-Gov. Jeb Bush to temporarily suspend executions. Mississippi's two grams of the anesthetic sodium thiopental is one gram lower than that used in all but three other states.

Unlike Kentucky, Mississippi does not have minimum qualifications for the IV execution team, does not provide the training required in other states and has no "back up plan" in the event of failed IV insertion or other errors in the chemicals' administration. In short, we haven't taken the necessary steps to make Mississippi's executions as humane as animal euthanasia.

But on April 23, the U.S. Supreme Court removed the stay it imposed in October against lethal injections in Mississippi, opening the door for Attorney General Jim Hood to seek the execution of Earl Berry. As it had in the case of Ron Foster, the attorney general's office asked for the execution date to be set on Earl's birthday, and while the Mississippi Supreme Court denied that request, it used that day to announce May 21 as the date the death sentence would be carried out.

From that point on, our team filed every pleading we ever heard of, and at least onean "original habeas corpus petition in the U.S. Supreme Courtԗthat I had never filed before. Despite the evidence of retardation, despite the proof that Earl never had the representation we claim to guarantee to all facing a death sentence, and despite the lack of safeguards against the premature injection of a paralytic drug that would suffocate Earl to death, no Court would re-open the case. We received word just before 5 p.m. on May 21 that the last appeal was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Then, the Gurney

And so Van Williams and I rode in the procession to the death house the afternoon of May 21. We had spent an hour with Earl and his family, watching Earl gamely try to keep his mother and grandmother from sobbing, hearing the chaplain talk about the genuine faith that Earl has nourished in his last years, and watching the camaraderie between the Berry family and the MDOC guards who had been assigned to them in this last week.

After the execution, it angered me to read Commissioner Chris Epps speak as if Earl's family didn't want to be there for him. The fact is that Earl asked his cousin Greg to keep his mother and grandmother from the witness room by all going home together, if necessary.

The vans lined up behind Unit 17, and MDOC went efficiently about the preparations for witnessing. Epps later claimed that more than 40 members of the Bounds family had asked to view the retribution for their matriarch's murder; we did not see nearly that many.

We were ushered into a small cinder-block room with a group of reporters. Through the glass we could see Earl strapped to the gurney, his arms outstretched and tied to beams extending perpendicularly to his body. It looked like a horizontal crucifixion.

Two sets of IV lines, one in each arm, wound back through holes in the cinder block to the secluded room where two paramedics would push the three drug cocktail into Earl's veins. The whole effect was like a seventh-grade science fair version of an execution. I wondered what the Supreme Court in D.C. would say if they saw it.

The execution chamber itself was full. At Earl's head stood Darryl Neely, former Jackson City Council member, now a member of the governor's staff. Next to him stood the infamous Dr. Stephen Hayne, whose testimony sent Kennedy Brewer to death row for 15 years for a crime he didn't commit. Epps stood at Earl's feet, next to the chaplain. Lawrence Kelly, the Parchman superintendent, stood across from Neely.

Earl's eyes were open, and as he told me he would, he declined to make a final statement. He continued to breathe and shudder for several minutes. Nobody will ever know whether he was unconscious when the second drug was given; Earl was paralyzed, unable to move or speak, even if he was suffocating, the chemicals burning him internally.

There has been considerable skepticism expressed toward our concerns about lethal injection. Almost all of the Supreme Court (with the exception of Justices Scalia and Thomas), and even the state experts in the Kentucky case, agreed that without sufficient anesthesia, the second and third drugs given in the "cocktail" are a quiet but excruciating form of torture.

Hayne declared Earl Berry dead at 6:15 p.m. on May 21, 2008. Darryl Neely, who had twice consulted his Blackberry during the execution, patted Hayne on the back and shook his hands. The efficient MDOC guards ushered us back to the vans, and we were soon on our way home in the warm Delta evening.

I did not attend the post-execution press conference, but many people commented to me the next day about the gleeful faces in the front page picture of The Clarion-Ledger. I'm not sure it isn't fitting, after all. If retribution is the goalif revenge is what Mississippians want from the death penaltywhy not celebrate it?

But pardon me for noticing that the Mississippi that boasts of having "a church on every corner" seems deaf to the words, "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone."

Jim Craig is a partner in the law firm of Phelps Dunbar, LLP, and is co-counsel in Walker v. Epps, the lawsuit challenging the Mississippi lethal injection procedure. He is also co-counsel for Dale Bishop, scheduled to be executed on July 23. He is a member of Mississippians Educating for Smart Justice (MESJ) and Fondren Presbyterian Church (PCUSA).

Tracks of Their Tears

'Dereliction of Duty'

JFP Index

• Wrongfully convicted Mississippians released from death row since 1976: 3 (Larry Fisher (1985), Sabrina Butler (1995), Kennedy Brewer (2008))

• Mississippi death row inmates executed in that same time: 9

• Mississippians executed since 1954 (when the state stopped using the electric chair): 40

• Number of those executed since 1954 who were white: 13

• Inmates currently serving death sentences in Mississippi: 63 (3 women, 30 white, 32 black, 1 Asian)

• Next scheduled execution: July 23, 2008 (Dale Leo Bishop)

• Anticipated executions for the remainder of 2008: 3 (including Bishop)

• Cost of executing a death row inmate, according to Corrections Commissioner Chris Epps: $14,000

• Median cost of a death penalty case, from trial to execution, according to a Kansas legislative audit: $1.26 million

• Median cost of a non death-penalty case, through end of incarceration, according to the Kansas study: $146,000

• States without a law granting prisoners access to DNA evidence that might exonerate them: 7 (including Mississippi)

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.