In 1961 civil-rights leaders travelled across the United States motivating young people to take hold of a small part of history. Speaking in churches, temples and schools, Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders called America's youth to tour the South in what they called Freedom Rides.

Inspired by the freedom rides of the 1940s, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) coordinated these rides after the Dec. 5, 1960, ruling in the Boynton vs. Virginia case, which determined that racial segregation in public transportation violated the Interstate Commerce Act. CORE leaders wanted to make sure the laws of the federal government were being upheld in the Deep South, where the law required "Jim Crow" segregation.

Six white students and six black students were among the first Freedom Riders to leave Washington, D.C., for New Orleans on two buses. The riders quickly learned that the Boynton ruling was not being upheld in the South. Police arrested many riders for sitting at "whites only" counters or using "whites only" facilities. The riders learned the practice of Gandhian non-violent protests. Even while officers severely beat and berated them, the riders did not fight or harm their attackers. From there, the Freedom Rides continued to grow.

Riders from across the country went to cities such as Montgomery, Birmingham and Anniston, Ala., to make a united statement that segregation would not be tolerated in any part of the country.

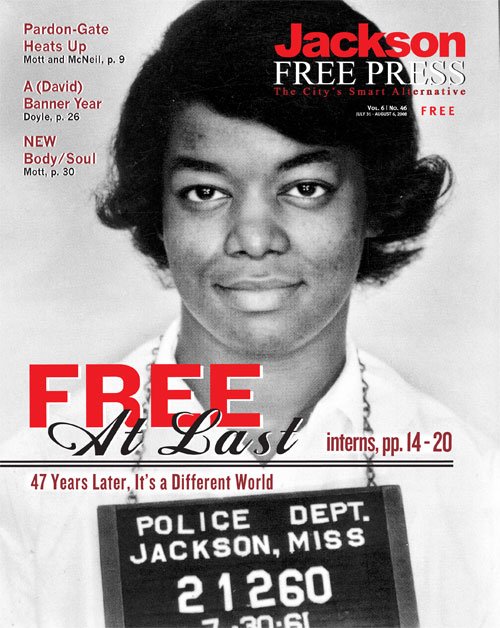

Finally, the Freedom Riders traveled to Jackson, Miss., one of the great strongholds of segregation. Not wanting Jackson to experience the humiliation and stigma that other cities suffered as a result of the violent treatment directed toward the Freedom Riders, the Kennedy administration negotiated a behind-the-scenes agreement with Mississippi and Alabama governors. The National Guard and state police would escort the Freedom Riders, but only if they could arrest the riders for trying to integrate segregated facilities, even though the arrests violated federal laws. Their arrests and subsequent booking photos give us eternally powerful portraits of everyday people who stood together as one to make an immeasurable difference.

REV. FRANCIS GEDDES: No Resistance

by Thomas M. Forrest

"We need a white Protestant minister."

Rev. Francis Geddes happened to be one. When the 38-year-old heard Pennsylvania Rabbi Allan Levine say those words on July 21, 1961, he was at Tougaloo College. Geddes had come from San Francisco to Jackson with the Fellowship Church of All People to listen to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Levine was calling for volunteers to help integrate the airport restaurant in Jackson. They had a racially balanced group of six or seven people already with some Catholics, Protestants and Jews. But they still had a spot open.

"I didn't come here to integrate a restaurant in an airport and go to jail," Geddes thought to himself.

It was 5 p.m., and Dr. King had already spoken. People from the group were about to go out into the community and speak with civic leaders, the chief of police, the mayor and city council members to try to get a diverse group of people to integrate the airport restaurant. When no one stepped up immediately, Levine repeated his question. "Well, we are on our way to the airport restaurant, but we still do not have a white, Protestant minister."

Geddes astonished himself by saying, "Well, you've got one now!"

Members of CORE then contacted Capt. J. L. Ray of the Jackson Police Department to let him know that the Freedom Riders were coming to integrate the airport restaurant. It was between 6:30 and 7 p.m. when the group arrived at the airport. While pointing to an imaginary line, Captain Ray says, "If you cross this line, I'll have to arrest you." When Geddes and the others began to cross the line where Capt. Ray was pointing, Ray said, "You're under arrest." Geddes and the others did not resist.

Officers placed Geddes in the paddy wagon where the other demonstrators spoke excitedly back and forth, annoying the driver. Even though the driver was driving 40 to 50 miles per hour, he abruptly slammed on the brakes, throwing the passengers onto the floor. He did this two or three times until they all started holding on tightly to thwart his game.

Upon arriving at the Hinds County Jail, Geddes saw an officer abusing a young, Jewish woman. The officer took one of her fingers, pressed it and twisted it hard against the ink blot.

When Geddes was served greens for lunch, a friend of his joked, "Well boys, you're in the South." Geddes was bailed out the next day, and he returned to his pulpit in San Francisco a couple of days later. Geddes only stayed in jail one night because the Jackson Police Department had been arresting so many protesters–up to a dozen a day–that they did not have any more room in Parchman, or the city or county jail.

Forty years later, in 2001, Geddes returned to Jackson to a very different reception.

"(We want to give you) a much warmer welcome this time than the last time they (the Freedom Riders) were in Jackson," former Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. promised the Freedom Riders at the reunion. Back at Tougaloo for the Freedom Riders Reunion, Geddes was amazed and proud of the transformation of Jackson since the 1960s. Geddes was impressed to see a black mayor, black city officials and a black population that exercised its voting power.

"It made me feel like I was part of something that was important and very valuable," he said in an interview from his home in California. He added that he was lucky to not face the challenges, harassment and violence that many other Freedom riders encountered. But he is happy to have shared in vital change.

Geddes recalled a woman who was speaking to the Freedom Riders during his first visit in 1961. The woman was standing on the sidewalk and said, "The people from the North are wasting their time." She believed that the people from the North would be arrested, and the protests would be unsuccessful. He remembers thinking, "Lady, you don't know what type of change is going to come out of this."

CHELA LIGHTCHILD: Singing In Jail

by Natalie Clericuzio

"It's hard to deny the truth when it's sung," Chela Lightchild says. "When someone is singing something that's true, it's harder to deny it than if they just say something. Sometimes a song is worth a thousand words." For Lightchild, music helped carry her and the other Freedom Riders through their time spent in jail: a week in jail for simply riding a train into the city of Jackson.

In 1959, Lightchild, a 23-year-old native of Maplewood, N.J., was living in Los Angeles. One evening she attended a play, "Fly, Blackbird," starring future Tony Awardwinner Mickey Grant. This play, written by UCLA professor Clarence Jackson, was a musical comedy that addressed civil-rights issues of the time.

After the performance, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech about the Freedom Ride that was going to occur the following week. Lightchild signed up for the ride that evening.

Despite her family's reservations about her participationher grandmother told her no nice Jewish boy would marry her if she went down there and returned an ex-conLightchild boarded the train from Los Angeles to New Orleans. With her fellow passengers knowing that Freedom Riders were on the train, Lightchild preferred to sit with some of her friends to make the time pass more quickly. To guard against identification, however, the riders sat separately. Lightchild settled for the long ride through the Deep South, feeling calm despite the possible dangers involved. In the middle of Saturday night, Lightchild's coolness dissipated thanks to an abrupt stop.

"The second night out, we were delayed around 1 or 2 o'clock in the morning in the middle of Texas, when the train stopped," Lightchild says. "We were terrified, each one of us. All the Freedom Riders had their heads out the window."

Twenty minutes later, the train started up again, presumably after just a routine stop. Believing no one would realize she was a Freedom Rider, Lightchild's nerves calmed again as soon as the train began moving.

After reaching New Orleans, Lightchild and the other riders, most of whom had never been to the South, underwent a non-violent training course as well as a course on adjusting to the southern accent. The Congress for Racial Equality even put the riders through mock sit-ins, where the riders would role-play and have to deal with ketchup being thrown at them without responding. With two weeks of training under their belt, they began the remaining train ride to Mississippi.

As the train pulled into the station in Jackson, Lightchild saw a crowd of police officers and FBI men. The police tried to rush the Freedom Riders out of the station quickly to avoid violence, while the FBI agents stayed put.

"You could always recognize (the FBI) because they had brown shoes and hats on, and white shirts with ties and a jacket, and it was summertime," Lightchild says. "They didn't interfere; their job was to watch."

Jackson police immediately planned to arrest the riders and place them in jail. Once the riders were outside the station, the officers called the names of the riders, one by one. When the police called Lightchild's name and Mary Hamilton's name (who was African American), they told the two women to step back. Lightchild had lived in California for some time and had a dark tan, while Hamilton was light-skinned with freckles. When the police told Lightchild to go with the other blacks and Hamilton to go with the whites, the two women tried to tell the police their mistake, explaining the reason for Lightchild's dark and Hamilton's fair skin tones.

The JPD of 1959 did not listen to their explanation and, thus, Lightchild and Hamilton integrated the squad cars. At the jail, when Lightchild was put in the African American cell and Hamilton in the white cell, the two also confounded the policemen by integrating the jail cells.

During the booking process, when the officer called her up for her mug shot, Lightchild recalls being glad she had worn her best clothes: a blue woolen, two-piece suit with a gray and white silk shirt and high heels. She had even taken the time to wear make-up and pluck her eyebrows, "stuff I wouldn't do today for anything," Lightchild says. All the riders dressed in nice clothes, and Lightchild wanted to portray herself in a specific manner in her mug shot.

"In my mug shot, I remember thinking, 'Look serious, but look friendly,'" she says.

Within the cells, the riders organized their time. A university professor of Greek provided classical Greek lessons; someone else taught French. Other times were reserved for meditation. However, singing was what really got the riders through the difficult times.

"We sang, and it was great," Lightchild says. "Everybody liked it: 'We Shall Overcome,' 'This Little Light of Mine' and 'Keep Your Hand On the Plow.' The music kept us alive. The music kept us alive, and the guards knew it. The moment we opened our mouths, they just hated it. They hated it. We sang good, too. That made them hate it even more."

For Lightchild, who was literally tone deaf before her time in jail, her time spent behind bars was a time of personal growth as well as an effort to stop injustice.

HELEN SINGLETON: Resolute in her Spirit

by Lisa Anderson

Helen Singleton tried to rest on the cold cement as a rat scurried around her and ran up a pipe. She grabbed a handful of trash from the filthy cell floor and stuffed the pipe's opening. Squeaking and squealing, the rat wanted to break through the barrier. Singleton had already spent one night in city jail, and that second night in county jail, she dozed off merely because she felt exhausted and tried not to dwell on what would come next.

It was Aug. 1, 1961, and Singleton, 28, wore a gray, striped prison skirt in Parchman Penitentiary. Her cell looked out on a 4-foot-deep corridor and a steel-doored room with a strapped chair. This was death row where Singleton was jailed during a summer when the prisons overflowed. "I can stand about anything here, but I think if they march somebody past me to the gas chamber, I'm gonna flip out," she thought.

Separated because of her race and gender from the rest of her group, Singleton sat behind bars alone with resolute spirit. "This must be done," she said. Singleton knew that she and her fellow riders were helping to revolutionize civil rights for black people, that they were testing the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that interstate travel must not be segregated.

Racism had a minimal impact on Singleton in Philadelphia, Pa., where she grew up, and in Southern California where she and her husband Bob moved for college in 1958, but she witnessed the realities of segregation when she visited her grandmother Hazel in Virginia during the summers. Her mother, Victoria, would have to cook chicken and vegetables the night before to make the trip to Virginia without stopping for food.

"We couldn't even stop at restaurants to use the restrooms," Singleton recalled. Once, her mother made cornbread that Singleton and her sister took to a white lady as a gift. The woman slammed the door in their faces and told them: "Don't you know any better? Go to the back door!"

In 1954, Singleton watched the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling on TV. "My goodness! They don't even go to school together down there?" she remembers asking herself. She and Bob participated in sympathy marches in California to support the sit-ins occurring across the country and boycotted the Woolworth's national chain for not serving black people.

Bob, UCLA's NAACP president, became the leader of the Los Angeles Freedom Rider group but didn't want Singleton to go on the July 30 Freedom Ride. "It's not fair for him to ask others to go and have me stay because it's too dangerous," Singleton thought. "I'm going."

Before the Singletons got on a plane for New Orleans with one change of clothes, they called their parents. Bob's mother cried. Singleton's parents were upset. On previous Freedom Rides, segregationists had bombed and burned buses and brutally beat riders.

The riders filed onto the train in New Orleans July 30, 1961, and sat quietly on the more than three-hour trip, knowing they would encounter some sort of a mob and FBI officers in Jackson.

No one in their group was physically injured, but they knew the possibility was real and they had trained in nonviolent civil disobedience before they left.

The group had brought minimal belongings, knowing whatever they had with them would be taken away. They knew they would be stripped, searched and given prison garments. Mississippi officials arrested Singleton and the 14 other Freedom Riders from Los Angeles as they walked into the "whites only" waiting room of the train station. The fact that whites and blacks were traveling together on a train from New Orleans to Jackson was reason enough for local police to warrant their arrests.

Singleton, on her first night in her single cell in the city jail, saw three other black women literally thrown into jail. One woman said that she had been arrested for driving without a license even though she was a passenger. And that is what helped motivate Singleton as she sat in jail for a month with the Freedom Riders.

The Riders sang peaceful songs, such as "We Shall Overcome," in prison. Singleton enjoyed the songs, but as a deadline-oriented person, she didn't want to sing about achieving goals "someday." She wanted set timelines for change. Riders also led hour-long lectures about the topics they knew best, speaking loudly into the corridor to reach one another. Singleton discussed art and anthropology.

Singleton wasn't Jewish, but asked to see the rabbi, anyway. The sheriff agreed, saying, "Your soul needs to be saved."

The rabbi wasn't supposed to bring news to the Freedom Riders–only spiritual talk–but turned to the deputy and said, "What, I can't tell them Roger Maris just hit another home run?"

Singleton left prison early because she had painful swelling around a tooth. After she discovered that she had an abscess, Singleton had to seek medical attention outside prison with the aid of an NAACP attorney. Bob remained in prison.

Just when she thought she'd have a break from the South, Singleton's family prepared for another trip to Virginia, her mother preparing chicken and vegetables once again.

When Singleton's family spoke about her Freedom Ride during the visit, her extended relatives–mostly professionals–disapproved. They said their businesses suffered, and black teachers struggled to get hired because of integration.

"These things will have to change," Singleton told them.

Finally, there came a year when Singleton's mother no longer had to cook the night before trips to the South. The Singletons had helped to make a step for black people, and her mother was thrilled. As she visited in later years with her family before she passed away in 2005, Singleton's mother had no problems getting service at restaurants and stores.

Singleton, now 75, is the mother of three grown sons and a retired art consultant living in Inglewood, Calif. She returned with Bob to Jackson in 2001 for a Freedom Riders reunion where they saw the black chief of police wearing the same uniform she had seen on Capt. J. L. Ray, a white chief, in July 1961. Singleton got chills.

The mayor ceremoniously gave the group keys to the city, and they drove up to take a tour of Parchman.

"It's changed institutionally," Singleton thought, yet there is much more change she wishes to see in this country, like having Barack Obama become the first black president.

When Singleton and the Freedom Riders made their trip in 1961, headlines about sit-ins, boycotts, bus burnings and other activist activities pervaded the newspapers and TV. People around the world heard about the Civil Rights Movement. She challenges the next generation to reach the same level of activism.

"Young people today need to be aware that even though we were fighting for the freedom in our day, what's going on now is that the liberties are abridged in the form of laws," Singleton says.

"They need to be vigilant about their civil liberties. I don't tell them what to do–I leave that for them to decide."

HEZEKIAH WATKINS: 'Outside Agitator'

by Thomas M. Forrest and Ward Schaefer

Hezekiah Watkins was only 14 years old when he and several friends decided to attend a mass assembly on civil rights at the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street in July 1961.

The Rowan Junior High School student walked from Watkins' mother's house on Rigsby Street to the meeting, where he stood as civic leaders told harrowing but exhilarating stories about the demonstrations, protests and sit-ins that were bringing attention to why segregation needed to end.

After the meeting, SNCC representatives asked for volunteers. After listening to the stories about protesters being attacked by vicious dogs and water hoses, Watkins and three of his friends decided they could no longer sit idly during a movement for freedom.

Watkins' first Freedom Ride experience was at the Greyhound Bus Station in Jackson on Sept. 7, 1961, when he tried to buy a ticket to Canton. He walked up to the station's front entrance on Lamar Street, where an officer told him to go around and use the rear entrance.

"No!" exclaimed the furious young Watkins. He stood his ground, refusing to go.

The officer arrested Watkins for his insubordination and took him downtown to the city jail. Alone with him, officers asked Watkins about his place of birth.

Watkins told the officers he was born in Milwaukee, Wis., but was raised in Jackson. They then sent him to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman.

Once he arrived at Parchman, guards placed Watkins in a cell by himself. While he was there, another prisoner told Watkins that he was being put on death row for being an "outside agitator."

Soon, help for Watkins came from an unlikely source. When white-supremacist Gov. Ross Barnett heard about a 14-year-old being placed on death row, he pardoned Watkins and demanded his immediate release.

Watkins was frightened on his way out of Parchman and had no idea what to expect because he did not know where he was going. He slowly gathered his belongings to leave.

Two guards placed Watkins in the back of a paddy wagon, alone, and began a long, hot drive. The truck was dusty, humid, and smelly, and had little ventilation.

During the ride back to the Hinds County Jail, the officers stopped at a convenience store to eat Hart's sweet rolls and rest, but didn't invite Watkins to join them.

The officers would not allow Watkins to leave the bus to urinate, and they refused to give him either food or water. They taunted him by drinking Barq's Root Beer in front of a weary and hungry Watkins just to immediately spit it out in front of him.

After three days, Watkins' mother came to get him from the jail.

"At first, she was totally aghast," Watkins says. Fearing for her son's safety, Watkins' mother initially did not want him involved in such dangerous activity. But the realities of her own life soon helped change her mind. "After her employer and others began to threaten her, she more or less changed her mind," Watkins adds.

"It energized me," he says of her support. He returned to the meetings and continued to volunteer with the Freedom Riders.

In another jail experience a couple of years later, several large officers200 pounds or more each, he recallsbeat Watkins so severely that he stills carries the scars from the attack on his head. The officers escorted him out of the jail, and in their vitriolic rage, they left him stranded on the corner of Fortification and Blair streets.

Watkins had no idea where he was, but the bright, hot sun continued the assault as he lay bleeding on the street in agony and fear.

"Was I aware of what I was doing, the cause, the bigotry, the hatred, the prejudice?" Watkins asked last month, sitting in the back of his store, Corner Food and Market, near Jackson State University. "Was my mind old enough or developed enough to know what was really going on? The answer to that question is no."

Although Watkins did not fully understand the institutional and systematic consequences of racism, he knew that he and his mother were not being treated equally in the workplace or for educational opportunities.

Wearing brown loafers, an off-white shirt and a blue apron, Watkins said he was arrested 100 times between Jackson and Clarksdale, as the organizer of marches, voter registrations and boycotts. He knows he and the Freedom Riders made a difference, although there is a lot of progress that needs to be made.

"I mentor several young men in this community on a daily basis. And they all have goals. I'm just telling them each day, 'Stick with it. You can reach that goal, whatever it is. If you stick with this and stay positive," he says.

PETER STONER: 'Will They Beat Us, Too?'

by Maha Mohamed

When the bus reached Jackson, Peter Stoner rose and walked toward the exit. He was scared, but he was determined to keep a brave face, if not for himself, then for the other riders. As he walked off the bus, he counted down the steps: 3, 2, 1. Finally his feet felt the streets of Jackson. Police officers were waiting for him. The images of earlier Freedom Riders who were caught by the police and beaten until their faces streamed with blood flashed before his eyes. Stoner stood on the street dazed, wondering, "Will they beat us, too?"

Today, 69-year-old Stoner sits in a green and white lawn chair on his patio. The late afternoon sun is high in the sky, which makes the heat unbearable. Luckily for him, his small patio offers protection from the wicked heat. He stares into the distance, looking at nothing particular, and sighs as he recalls the days of his youth.

In 1960, 22-year-old Stoner was studying chemistry at the University of Chicago. Originally from Berlin, Pa., Stoner moved to Chicago to attend school and look for work. He worked as many jobs as he could at the university to support himself. Stoner spent time with young idealistic people like himself who wanted change. But he thought, "What possibly could a group of young students actually do?"

Later that year, Stoner visited New Orleans. After leaving the public library one afternoon, he went to drink from the water fountain. He found one designated for "whites" and the other for "colored." As he stooped to drink, he realized that the "colored" water fountain was set lower. Horrified, he finally realized what cause he could fight for. "I just felt it was a system of organized oppression, and people in the South were victims of the law," Stoner says now.

When Stoner heard about the Freedom Riders project, he took a bus to Montgomery, Ala., to join the other men and women determined to test the 1960 Supreme Court ruling, which illegalized segregation in all interstate public facilities.

Leaning back in his lawn chair, with his large hands folded on his lap, his giant sea-blue eyes appear to grow as he remembers the night when he reached the city.

In Montgomery, the Freedom Riders spent the night at Martin Luther King's house. Unfortunately, the reverend was not in town; however, Stoner remembers that he could hardly tell the house had been bombed six years earlier.

The next day, six or eight others embarked to their final destination–Mississippi's capital city.

Though it would only take four or five hours to reach, Stoner recalls "some of the colored women wanted to sit in the front seat; it was important to them to not sit in the back of the bus."

In Jackson, Police Chief J.L. Ray arrested the riders. Stoner says he and the others were lucky because the police officers did not hurt him. Instead, they whisked him away to the notorious Parchman Penitentiary.

When Stoner reached Parchman, he feared what the officers would do with him. "I cannot say I was not scared, but the Lord watched over me," he says. Stoner and about 50 other white men were placed altogether in a large room, complete with beds and even a bathroom. The riders were separated by both race and gender. The Freedom Riders were also kept separate from the other prisoners of the penitentiary. Stoner says it was not all bad sitting in that room. "We were just in a room, and kept there for I don't know, six weeks, but we could get water anytime we wanted, and we were fed."

For those six weeks, Stoner and the other men got to know one another. He was glad to find that he knew a few of them from Chicago. He says that since then, though, he has not met any of them again.

After his release, Stoner did not return to Chicago. Instead, he enrolled at Tougaloo Southern Christian College in 1961. He did not give up on his dream to make a change in America's system. One of his ambitious projects included helping Mississippians register to vote. During this time, he worked for the Congress of Racial Equality, the organization that produced the Freedom Rides. After he graduated from Tougaloo in 1963, he worked as a full-time civil rights worker for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Since then, Stoner has made Mississippi his home. He received both his master of science and doctorate in chemistry at the University of Southern Mississippi. Now he is writing a book, "The Fried Chicken Murder," involving another story from his youth about his stepmother's attempt to take his father's farm.

Back on the patio, a plump sherbet-colored cat brushes against his legs. Stoner returns to the present. He leans over and gently strokes the cat's long golden whiskers.

He looks up and proudly says: "I felt that the Freedom Rides were a way of successfully doing something about the situation. People have more civil rights. Many things have gotten better; some things have stayed the same; and some things have gotten worse. But race relations have greatly improved; a person like Barack Obama could have never run for president back then."

A Civil Rights Glossary

by Matt Caston

CORE: A group of African Americans on the campus of the University of Chicago founded Congress of Racial Equality in 1942. CORE has fought for freedom and equality throughout every decade. Whether it was against Jim Crow laws in the '40s, the Freedom Rides of the '60s or crusading for community development in the '90s, CORE has always been a champion for justice.

SNCC: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (Snick) originated on the campus of North Carolina's Shaw University in 1960. The organization grew out of student meetings led by Ella Baker. SNCC played a major role in civil rights protests such as Mississippi Freedom Summer and the 1963 march on Washington. SNCC has had great leaders like Bob Moses, John Lewis and Stokely Carmicheal.

SCLC: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference grew out of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956. Originally headed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ralph David Abernathy, the organization grew to incorporate surrounding churches and other community organizations.

COFO: Council of Federated Organizations was an umbrella organization inspired by Bob Moses of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. COFO was made up of many smaller civil-rights organizations throughout Mississippi, and its purpose was to unite them and give them a common goal.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.