Prosecutions of a Mississippi Supreme Court justice and a wealthy Gulf Coast attorney considered friendly to Democrats are at the center of the most spectacular congressional investigation of political prosecution in the nation's recent history.

The Jackson Free Press addressed suspicions about the prosecution of Justice Oliver Diaz and attorney Paul Minor last November with a story detailing the U.S. Department of Justice's preference for Democratic targets. That story later became a small footnoteliterally, referenced in a congressional reportin the probe as it unfolds in Washington, D.C.

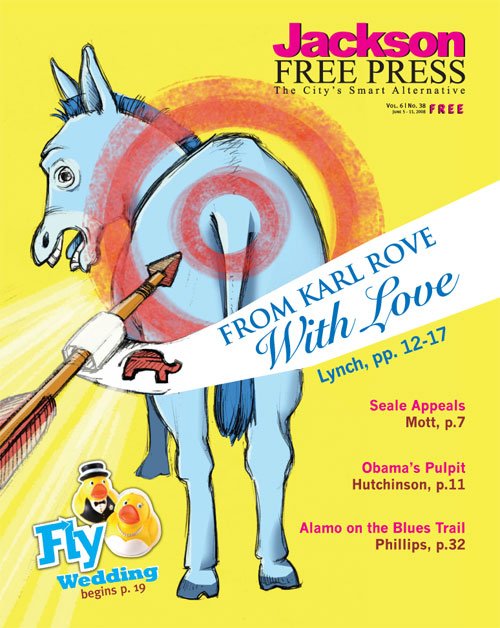

It is a scandal that points, at least indirectly, to the Oval Office. Now dominated by Democrats, the U.S. House of Representatives Judiciary Committee is investigating allegations that former White House Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove used the U.S. Department of Justice as a battering ram to break down the Democratic Party in southern states, and compromise party officials all across the nation with investigations and indictmentsmany of them bogus, or overblown.

In some cases, such as Minor's, the House is looking at whether the White House and the U.S. Department of Justice pursued accusations comparable to those that landed him in federal prison for 11 years as strongly against Republicans who committed similar transgressions.

The April 17, 2008 congressional report, "Allegations of Selective Prosecution in Our Federal Criminal Justice System," catalogues numerous allegations of political targeting in Alabama, Mississippi, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan and Georgia. It also notes a strong possibility of the "political interference of Karl Rove."

The House Judiciary Committee has tried to enlist Rove to contribute to the report, but he thumbed his nose at House members on a recent Sunday news show, saying any subpoenas for him to testify will have to play out in federal court.

The committee wants Rove to appear July 10 to address the White House's role in the dismissal of nine U.S. attorneys in 2006 and the prosecution of former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman, as well as other possible political prosecutions such as those of Diaz and Minor.

Rove, a college dropout who helped put Bush into the White House in 2000, accused the committee of wanting "to be able to call presidential aides on its whim" to testify.

The committee also issued congressional subpoenas to Josh Bolten, Bush's chief of staff, and Harriet Miers, a former counsel who Bush tried to put on the Supreme Court.

Bush wants to keep his secrets secret, however, and cites executive privilege in keeping all three out from in front of the committee and, above all, out from under an oath.

Rove's lawyer, Robert Luskin, responded to House Judiciary Chairman John Conyers Jr. with a letter accusing the Democrat from Michigan of provoking "a gratuitous confrontation" with his client on a case that is "already being litigated in U.S. District Court." Luskin expressed incomprehension as to why the committee "refuses to consider a reasonable accommodation" that Rove offered committee members in good faith prior to the subpoena. His personal demands meant committee members would have to forgo a sworn oath of honesty in interviewing him and would also have to agree not to have his statement transcribed.

Conyers, possibly revealing the extent of his faith in Rove's unsworn, unrecorded statements, issued the congressional subpoena soon afterward, on May 22.

"Although (Rove) does not seem the least bit hesitant to discuss these very issues weekly on cable television and in the print news media (Rove is now a Fox News analyst), Mr. Rove and his attorney have apparently concluded that a public hearing room would not be appropriate," Conyers wrote in a press statement. "Unfortunately, I have no choice today but to compel his testimony on these very important matters."

Disloyalty Oaths

The Rove connection to Siegelmanand later Diaz and Minororiginally sprang from the House Judiciary Committee's interest in the U.S. Department of Justice scandal surrounding a list of U.S. attorneys targeted for firing. In January 2006, Justice Department Chief of Staff Kyle Sampson began pegging U.S. attorneys to ax. That move was not unexpected. After all, former White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales had discussed with Sampson the possibility of replacing all or some of the 93 U.S. attorneys, and the executive office inserted language in the 2005 re-authorization of the U.S. Patriot Act that would make replacing U.S. attorneys even more effortless.

The U.S. Senate later confirmed Gonzales as attorney general in 2005, but White House Counsel Miers was still pushing the mass-firing plan to Sampson in February 2005. In March 2005, Sampson concurred with Gonzales and Miers, e-mailing a list of targets back to Miers. Sampson felt "loyalty to the President and Attorney General" was of considerable importance, and ranked the U.S. attorneys by that loyalty, according to information requests from The Washington Post.

The name of Washington state U.S. Attorney John McKay is of particular interest to the Judiciary Committee. His name was not initially on that list, but appeared on later lists after he blew off Washington state Republican Party Chairman Chris Vance's criticism of McKay's faltering investigation of the 2004 governor's racean investigation that could have changed the 129-vote outcome that delivered Democrat Christine Gregoire into Washington state's governor's office.

McKay later admitted in 2007 testimony before Congress that more than one Republican had contacted him. McKay also received a call between 2004 and 2005 from Washington state Rep. Doc Hastings' chief of staff, Ed Cassidy, asking about the status of a voter fraud case. Cassidy warned that GOP activists were pushing the investigation before McKay abruptly shut down the conversation with a warning that he could not discuss the status of investigations. In September, McKay's name later popped up on a following list of "[U.S. Attorneys] We Now Should Consider Pushing Out," compiled by Sampson.

Unreleased government records obtained by The Washington Post show that the Justice Department listed 26 U.S. attorneys as candidates for firing, including nine who were actually pushed out in 2006. The name of Mississippi U.S. Attorney Dunn Lampton was on the original list of 26. Unlike nine others who were fired, Lampton still holds his job, and some Democrats question how he managed to keep it.

Anonymous sources began leaking news in 2002 that an investigation was underway against well-known Mississippi attorney Paul Minor, a huge Democratic campaign donor. Lampton officially unveiled his investigation in 2003, listing indictments against Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Oliver Diaz, Minor, Diaz' wife Jennifer Diaz, and judges Walter "Wes" Teel and John Whitfield, who took campaign loans from Minor. The prosecution characterized the loan as a bribe because Minor paid off the difference of their loans when the money came up short.

Diaz and the other judges had been up against the powerful influence of the U.S. Chamberan organization that does not have to disclose its donorswhich pours huge sums of money into judicial campaigns of corporate-friendly judges who do not favor plaintiffs in lawsuits. That strategy benefits both the corporations being sued, and helps limit the campaign donations that plaintiff attorneys can give the party they tend to support: the Democrats.

The effort has largely succeeded, with a state Supreme Court that routinely reverses Circuit Court rulings against corporations. In one 2007 case, the court even supplanted the 2006 decision of a Hinds County Circuit court jury with its own opinion, ruling in favor of Prudential Insurance Company of America in a $36.4 million lawsuit against it. The court reversed the jury's decision not because of bad evidence or improper jury instruction, but because it disagreed with the jury's finding.

"Why have juries if all you need to do is overturn them?" asked attorney Alex Alton, who represented the plaintiffs in that case.

A Weak Case Finds Help

The prosecution's case against Diaz was woefully weak. Proof of the alleged bribe must be made clear to a jury, but Diaz had not presided over any of Minor's cases. Even Lampton admitted to the press in 2005 that the first indictment against Diaz was going to be difficult to sustain before a jury.

Lampton no longer comments to the Jackson Free Press regarding the Minor-Diaz issue, but he told the JFP last year that the bribery case was not the one he had wanted to pursue against Diaz. "The Justice Department and I strongly disagreed on how to prosecute that case. The Justice Department got their way, and I believe there was sufficient evidence to convict him, but maybe not for what he was charged," Lampton said.

With no quid pro quo to weigh in on, a jury found the case against Diaz insufficient and acquitted him in August 2005, and could reach no verdict on the other defendants.

Three days later, however, Lampton was ready with a follow-up, shaking out a second indictment for tax evasion against Diaz and his wife. He also said he would retry the cases against the other judges.

The prosecution hoped that Diaz and his wife had improperly recorded $42,000 of Minor's campaign loan on their tax returns as personal income. Many politicians separate campaign loans from personal income on their taxes, however, and the couple had amended and paid the difference on all their tax miscalculations prior to the tax-evasion indictment. Fearing their children could soon be without parents, however, Diaz told the JFP that his wife pled guilty and took two years' probation. The gamble proved unnecessary, though. The jury dumped the case after only 15 minutes of deliberation.

Raw Story revealed in a 2007 article that Lampton had not properly disclosed his own campaign loan proceeds and that he was under FEC investigation at the time of his appointment to the U.S. Attorney's office. Whitfield said as much in his own July 2007 letter to the Judiciary Committee, wherein he pointed out that the FEC fined Lampton for, among other reasons, "his failures to properly disclose the identities of contributors and receiving monies from an illegal PAC."

Whitfield told the Judiciary Committee that Lampton did not even try to hide his opinion on his perceived politics: "He looked me in the eye and told me during the initial (investigation) interview that I would not be involved in the (investigation) if I 'had not been so liberal while on the bench.Ҕ

Not So Minor Pain

Diaz was found not guilty in the 2003 bribery indictment, but Teel, Whitfied and Minor were up for a retrial because the jury had not reached a decision in their case.

This time around, the prosecution took no chances. Helped along by Republican-appointed presiding Judge Henry Wingate, the prosecution succeeded in ruling out the need to prove bribery in a bribery trial. Wingate had overseen the first trial that found Teel and Whitfied innocent, but Diaz said Wingate "abdicated his role" as a moderator and "changed many of his rulings" from the first trial.

"A 'quid pro quo' is a basic requirement in any bribery trial, and Wingate's ruling on this issue sealed the case for the prosecution," Diaz wrote in a 2007 letter to the House Judiciary Committee. "This was clearly an error, and one is left to wonder why the judge changed his rulings."

Wingate also allowed instructions that the jury could find the defendants guilty "even (if the defendant judges') rulings were legal and correct, that the official conduct would have been done anyway, that the official conduct sought to be influenced was lawful and required by law, and that the official conduct was desirable and beneficial to the public welfare," Diaz wrote.

"Because they could not show that the rulings were not correct, prosecutors argued that the simple existence of the loans with rulings by the judges equated to federal bribery," Diaz said in his letter. "With vague charges by prosecutors and rulings like these from the trial judge, it is no surprise that the second jury was able to convict."

Diaz voiced suspicion of "political persecution" that sent "three innocent men ... to lengthy terms in federal prison."

"They were selected for prosecution based solely on their political activities. They were subjected to vague charges of corruption which were impossible to defend against ... . They have been vilified, demoralized and financially bankrupted."

Last year, Lampton denied that the trial was a witch hunt. "It was absolutely not political. The jury heard all the evidence and convicted Minor, and I feel real comfortable about that," Lampton told the Jackson Free Press.

To this day, Minor's father, columnist Bill Minor, says Wingate's attitude has hardly softened since Paul's conviction in September. "We've been trying to get Paul's appeal moving since his conviction last September," Minor said, "but the hardest thing to do is get the case transcripts from Wingate's court. They had such a hard time dragging that out of him."

Others say that Minor deserves the scrutiny he got. Jackson attorney Brad Sessums testified in 2005 that Minor had approached him and his partner Bobby Dallas in 2001, looking for a political donation of "about $20,000 or $40,000" for Diaz, pointing out that Diaz had done the two a good turn in convincing the Supreme Court to uphold a $9 million medical malpractice verdict awarded to one of Dallas' clients.

Sessums said he was concerned enough about Minor's approach to contact the U.S. attorney's office. "The other side had filed a petition for re-hearing before the Supreme Court ... at the time this phone call was made trying to get us to make a significant contribution to retire some of Diaz' campaign debt," Sessums said. "... I don't think it's coincidental that that call was made on the same day the petition was filed," Sessums said.

Minor had fallen short of a "give us this money or Diaz may change his vote" threat, Sessums said. "I had no reason to suspect that Diaz knew Paul was making that call, and Paul was smart enough not to come out and make a direct threat, but it was clear to me what the threat was," he said.

Sessums said neither he nor Dallas donated money to the cause, specifically because they had a case before Diaz. The court did not change its decision.

Minor was acquitted in that case of attempted extortion, but he was convicted of mail fraud in September 2007, and was immediately shackled and led to jailrare treatment for most white-collar crimes, especially considering laws addressing Minor's transgressions did not exist in Mississippi at the time of their occurrence.

Sessums, a trial lawyer, said the case involving Minor made him "sick to his stomach" because of the damage it did do the industry. "The profession had a bad enough reputation before this came out. The industry was sort of staggering to begin with, and they've really whacked it over the head even more," he said.

Minor submitted his own letter to the House Judiciary Committee in 2007, saying that at the time of his loan guarantee to the judges, "it was not against the law in Mississippi for lawyers to do so. Moreover, it was common practice for attorneys to make loan guarantees to judges and to appear before judges to whom they had made political contributions." Minor added that another attorney who frequently made such loans was Richard "Dickie" Scruggs.

Minor was particularly bitter in his letter about Scruggs. Scruggs, the brother-in-law of now-retired U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, regularly guaranteed loans for other judges, but saw no indictments from the U.S. attorney's office until after Congress began investigating accusations of political persecution. Minor noted in his letter that special FBI agent and forensic accountancy expert Matthew Campbell questioned why Scruggs was not also getting booked on the same charges and was "removed from the investigation and transferred to Guantanamo Bay."

"Scruggs, however, had contributed $250,000 to the Bush-Cheney presidential campaign and (the) GOP in 2002," Minor wrote. "The Federal Election Commission Report of September 14, 2000, shows that Scruggs and his wife gave over $500,000 to various Republican causes. Scruggs also guaranteed a $500,000 loan to Republican Lieutenant Governor Amy Tuck a leader in the effort for tort reform (in Missisippi)."

Slimy Trail to Alabama

Minor's fate is worse than former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman. Siegelman, a popular politician who has occupied more than one political post in his home state, made the mistake of being a Democrat in Alabama under Rove's U.S. Department of Justice, but currently is out of jail on bond.

Rove invaded Alabama during the 1990s, riding an anti-regulation wave against "activist judges," similar to the wash engulfing Mississippi via the U.S. Chamber at the turn of the century. The political change had caught on in Rove's home state of Texas, where Republicans now dominate the Legislature and statewide offices, and worked well in Alabama with the help of Republican consultant William Canary.

Like Diaz and Minor, federal authorities hit Siegelman with a bribery indictment, one that sentenced him to more than seven years in prison in 2006. Unlike Minor, however, Siegelman's lawyers got him out on appeal, convincing a federal appeals court that the prosecution's case had big holes.

Siegelman is vocal about what he feels as a GOP war on Alabama Democrats.

"They've done anything that was necessary to retain or gain power. ... They have gone after Democratic candidates, and they've gone after contributors who've supported Democrats in an effort to cut off their main supply and stop anybody that they thought might be a rising star at some level," Siegelman told the JFP earlier this month.

Siegelman's claims go way back to his successful 2002 re-election for governor. Siegelman calls it a success, even though Republican opponent Bob Riley occupied the governor's office the following week. Siegelman appeared to have won re-election on Election Day, but then mysteriously lost votes after one county's vote machine was left in the hands of Republican operatives for a night.

"There was an analysis of the vote patterns in that county, and it showed an electoral anomaly that statistically and mathematically could not have happened," Siegelman said. "The only possibility was that it was electronically manipulated, and the two people who claimed credit worked with Rove and the Republican Party."

Kitty McCulloughalso known as Kelly Kimbroughwas Rove's business partner at his political consulting firm K. Rove & Company in Alabama. The state Republican Party gave her credit for finding the irregularity that Siegelman describes as vote theft. The other operative, Dan Gans, is a self-described electronic ballot security expert who later went to work for a Tom Delay and Jack Abramoff-related company, The Alexander Strategy Groupwhich has been implicated in the Abramoff scandaland had close ties to now Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour. Gans claimed credit on his Web site for finding the votes that delivered the election to Riley.

Writing for Harper's magazine, Scott Horton noted other connections between Abramoff and the Siegelman issue in a June 2007 article. Riley's congressional press secretary, Michael Scanlon, left Riley to work for U.S. Rep. Tom Delay before going to work for Abramoff. Scanlon later pled guilty to conspiring to commit bribery and testified against Abramoff in 2005.

Gans and Kimbrough were two people, among others, who lingered around a Baldwin County voting machine after the reporters had declared victory for Siegelman and gone home. The very next day, about 5,000 votes from that county magically switched to Riley. The odd thing about the new votes was that many of the voters choosing Republican Riley had chosen Democrats on down-ticket races.

"It was as if the voters went Democrat on every ticket, but then got to the governor's race and inexplicably went Riley," Siegelman said. "Keep in mind that this anomaly only happened in this one area of this one county, the one with Republicans hanging around the voting machine in the middle of the night."

Local Republicans agreed to a recount the next day, but Alabama Attorney General William Pryor, a Republican whose 1998 campaign was managed by Rove and Bill Canary, ordered that anybody trying to hand count the ballots were headed for jail.

"We were at a standoff," Siegelman said. "The votes were then illegally certifiedunder Alabama law you can't certify the votes until after 12 noon on Fridayby the secretary of state and the attorney general, maybe a day or two days earlier. Once the vote was certified we had to file an elections contest, taking the case to court."

But Rove and the anti-plaintiff lobby had already worked their magic on the Alabama State Supreme Court, similar to the transformation of the Mississippi Supreme Court. Sessums, for example, acknowledges the shift in attitude in this state, after the "jackpot justice" fury hit Mississippi, egged on by a non-questioning media that regurgitated the U.S. Chamber rhetoric.

"We tried a neurosurgery case up in Lee County back in February 2002. ... The neurosurgeon got stuck with a $3 million verdict. He appealed. ... It was affirmed 5-3 our way. Then they filed a petition for re-hearing. By the time the decision came up again, the pro-business folks had gotten Jess Dickinson to run against (former Justice) Chuck McRae and beat him, and damned if they didn't reverse and remand that prior affirmed case 6-to-1 against us," Sessums said.

The spanking-new anti-plaintiff court was open and ready for business in Alabama, too, according to Siegelman.

"We knew it would be virtually impossible to get a good ruling out of them, and we were very fearful of going into Baldwin County. We'd had some experience with the federal judge down there, so we decide that it was time to walk away from the contest and live to fight another day," he said.

But according to Alabama Republican campaign volunteer Jill Simpson, Rove and company were not yet finished with Siegelman.

The Word of an Insider

Simpson issued a sworn statement to Congress last year that she had overheard conversations suggesting that Rove was involved in Siegelman's post-election prosecutions. Simpson described a Nov. 18, 2002, conference call between Riley's son, Rob Riley, Bill Canary and Bob Riley's campaign flacks. Simpson alleged that Canary had said during the conference call that Rove "had spoken" with the Department of Justice about chasing Siegelman and had advised Riley's staff "not to worry" about Siegelman because "(Bill Canary's) girls would take care of" the governor.

Both Riley and Rove claim the conversation never happened, though Simpson identified telephone records reflecting the Nov. 18 conversation in her May 21, 2007, affidavit. She also identified other phone calls between her and Riley during the 2002 campaign season, as well as a series of letters showing that she had regularly worked on legal matters with Riley since 1998, even though Riley told the Northwest Alabama Times Daily in 2007 that she was just an old-school friend whom he had not seen for "13 or 14" years.

Riley also made himself out as a liar when he told reporters that "Rove has no idea who Rob Riley is." A 2007 Time Magazine piece reported one of Simpson's and Riley's joint clients recounting Rob Riley mentioning Karl Rove "about four or five times" as someone he was begging help from to "settle our business in Washington."

Riley refused to speak to the House Judiciary Committee under oath last October. He also has not returned calls from the Jackson Free Press.

Simpson said Bill Canary's "girls" in charge of dealing with Siegelman were Bill's wife, Leura Canary, and Alice Martin. Both were appointed by Bush in 2001 as Alabama U.S. attorneys. Simpson also testified that Riley told her Judge Mark Fuller was hand-picked by the witch-hunt team to prosecute Siegelman's 2005 case. Fuller, Simpson recounted, would "hang" Siegelman, according to Riley.

Rove claims that he had no hand in the Siegelman case, telling news analyst George Stephanopoulos that he "found out about Don Siegelman's investigation and indictment by reading about it in the newspaper."

When Stephanopoulos insisted that his statement was not a denial, Rove repeated, "I heard about it, read about it, learned about it for the first time by reading about it in the newspaper."

The question of the prosecution's real motives behind their pursuits in both the Mississippi and Alabama cases still hangs in the air, with or without Rove's influence. Siegelman bitterly points to the connections between his prosecution and his former gubernatorial rival.

Polls showed Siegelman favoring well among Alabama voters and that he would take Riley to the cleaners when he ran again in 2006. But in 2004, Martin indicted him with charges alleging he had bid-rigged state contracts. The case was so shoddy that it evaporated before the trial date.

The Alabama U.S. attorneys made a good team, however. Leura Canary made public an indictment in October 2005, for bribery, mail fraud and wire fraud, as well as obstruction of justice. Much of the case was built upon alleged bribes from Alabama lobbyist Lanny Young (who had already pled guilty in 2003 and 2005 to bribing officials). Young said he had given money to Siegelman, as well as a $500,000 donation from Alabama businessman Richard Scrushy to a state lottery initiative funding higher education, that Siegelmanand many Alabama residentsfavored.

An October 2007 edition of Time Magazine reported that Young had also illegally routed money to many Republicans, including former Alabama Attorney General and current U.S. Sen. Jeff Sessions ($22,000) and federal Judge William Pryor ($15,000), but Alabama U.S. attorneys have yet to chase those cases.

A jury acquitted Siegelman of 25 of the 32 indictments that Canary brought against him, but convicted him for the charges relating to a $250,000 check from Scrushy. In retrospect, however, the issue of the check should not have held such weight.

"The original testimony was that the check for $250,000 was given to the capital office by Richard (Scrushy), signed by him on this company on a certain date. But the check was actually delivered by Federal Express to a different office, from a different company, signed by a different person on a much later date," Siegelman said.

The letter, alongside Siegelman's conflict-of-interest issues, threw a big enough cloud of doubt over the case to drive the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals to order Siegelman released on bond pending his appeal.

Last week, 54 former attorneys general filed a brief supporting Siegelman's appeal. Robert Abrams, a former New York attorney general who authored the brief, said the signers had "strong feelings" that an injustice had been done.

Apparent conflicts of interest racked Siegelman's case. Mark Everett Fuller, the judge whom Simpson said would "hang" Siegelman, had been on the Republican Executive Committee when Siegelman was running for office. As governor, Siegelman and Fuller butted heads over a salary increase that Fuller tried to implement for one of his employees. The dispute went to the state supreme court, where Fuller came out on the losing side. Fuller had also been accused by one of Siegelman's DA appointees of falsifying payroll records with intent to defraud the Alabama retirement system.

Fuller did not return calls to the Jackson Free Press.

Alabama prosecutors had other suspicious ties. Leura Canary was the wife of Bill Canary, the campaign manager of Siegelman's opponent. Siegelman's attorneys forced Canary to recuse herself from the prosecution, but they say they never saw her recusal papers.

"It's still in contention whether or not Canary recused herself from the prosecution. We demanded she recuse herself. She was called to Washington, and she came back and said she was voluntarily stepping down, but when we asked for her recusal papers we were denied," Siegelman said.

Siegelman's lawyers say that the Department of Justice still refuses to turn over more than 500 documents related to his case to either Siegelman or the House Judiciary Committee.

Diaz said he never saw Lampton's recusal papers, either. Lampton put FBI Special Agent Kevin Rust in charge of the prosecution, but Rust had donated money to Diaz' opponent in the Supreme Court race.

Lampton played down the donation last year, telling the Jackson Free Press that Rust's contribution was limited to "buying a painting for $200," and explained that "the FBI assigned the agents," not him.

Minor had his own reason for wanting to remove Lampton from the prosecution. Lampton's family owns Ergon, a Forbes 500 company that Minor sued for millions of dollars. Minor was still working on the Ergon suit in 2002, the year Lampton unveiled the case against Minor.

Lampton denied to the Jackson Free Press that the prosecution was biased. Ӆ Every time I've prosecuted a public official, the claim is it's vindictive, whether it's a Republican or a Democrat ... ."

The Judiciary Committee, nevertheless, noted in its April 2008 report that Lampton's eagerness to pursue the cases against Diaz, acknowledging his three-day reprieve between indictments against the judge, as well as Lampton's quote to the Jackson Free Press that more indictments could be brewing.

"There are other things I am aware of regarding Justice Diaz that caused me to refrain from commenting further on [the weakness of the prior case], but it will come out later, and you'll see ..." Lampton told the Jackson Free Press last year.

He has not clarified his statement since speaking with the JFP for that article.

The committee is not hiding its suspicion of a connection between Lampton's prosecutions and the state Democratic Party: "Other concerns, besides the possible defunding of Mississippi Democrats by intimidating possible donors, such as the trial bar, have been raised about the prosecution. The indictment was announced just 90 days before the Gubernatorial election between Democratic Governor Ronnie Musgrove and Republican challenger Haley Barbour, in which issues of Democratic 'corruption' were prominent," the report states.

A New Banana Republic?

Perhaps the greatest affront to America, out of all the issues connected to Rove and his war on Democrats, is the emerging sense of fear. Many members of the defense in both the Alabama and Mississippi cases say they were the victims of shady home invasions, as if criminals were ransacking their belongings, looking for something without the virtue of a warrant.

Diaz said he had stated publicly that he would be out of town attending a graduation, so perhaps the burglary should not have come as a complete surprise to him. But he added that the burglars did not appear to target the more obvious possessions.

"They kicked in my door, and in the living room area where the door opened into there were computers, television, stereos, CD, all the electronic valuables were right there in that room, but none of them were missing. The room was obviously rummaged through, but nothing was taken. I'd had a laptop computer sitting right beside the door. If they'd wanted to they could have simply grabbed it and run," Diaz said.

The office of Mississippi Judge John Whitfield, who was tried along with Diaz and Minor, was set on fire. Whitfield could not be reached to speak further on the matter, but Diaz said Whitfield's Gulfport attorney Michael Crosby reported that burglars had left a mess in his business office and in the hotel room he was staying in during the trial.

Crosby did not return calls to the Jackson Free Press.

Alabama had its own share of persecutions, on par with something out of a KGB movie.

Siegelman's own home was broken into twice during his trial, and his workplace was broken into on one reported occasion during the height of the investigation.

Even Dana Jill Simpson, the whistle blower who approached the House Judiciary Committee with her report on political wars in Alabama, became a victim of arson in February 2007, months before she came forward with her testimony. During that same month, she claims another car ran her off the road. According to Raw Story, a police report revealed Rainbow City resident Mark Roden to be the driver who pulled into her lane. Simpson told Raw Story that "when the trooper asked (Roden) for his employment information, Mr. Roden said that he was an officer with the Attalla Police Department. He was then allowed to leave without a citation."

"I wouldn't think much of my own break-in, but once you combine it with all of the other occurrences that have happened to other people involved in this same situation, it does raise the conspiracy theories to a certain level of credibility," Diaz said.

Siegelman's attorney, Vince Kilborn, said Rove would most likely get indicted for obstruction of justice, though he said there are bigger crimes he could face.

"It is a federal crime to use federal assets for political purposes. If, let's say, Rove and anybody else used a federal e-mail system or assets of any kinda computer, telephone or whateverfor political reasons, that already crosses the line. It would be like stealing public money, like taking Air Force One for a political trip and charging it to the public."

But what of the moral crime of using the nation's resources to beat the country's political system down to a one-party system? A 2007 academic study published by University of Missouri communications professor Donald Shields suggests the U.S. Department of Justice had a strong preference for hunting Democrats. The report found that of 375 investigations released to the public, 10 involved independents, 67 involved Republicans, but an incredible 298 involved Democrats.

If the Republican-led Justice Department was systematically disemboweling Democrats, what would be the crime? That's a question that Kilborn said he can't readily answer, but one that he believes the U.S. Supreme Court should find an answer very quickly.

"There will probably be four Supreme Court nominees coming up, and if Democrats take the presidency, there could be a shift in the court," Kilborn said. "And this issue, they will find, will cut very clearly across party lines.

See also:

Nov. 7, 2007 - A Minor Injustice - Scott Horton, reprinted from Harper's

Nov. 7, 2007 - Dem At Your Own Risk - Adam Lynch

Nov. 27, 2007 - The Permanent Republican: Majority - Part 1 of a series by Larisa Alexandrovna and Muriel Kane

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.