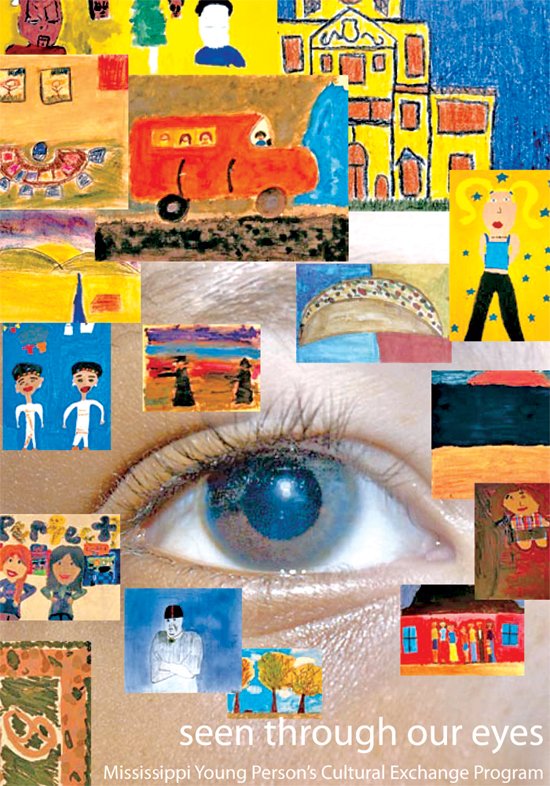

The Mississippi Young Person's Cultural Exchange Program placed culturally diverse students in an artistic setting. Photo by Courtesy Patricia Crosby

Tucked away in a classroom of the Mississippi Museum of Art, the work of over 50 young Mississippians covers a full wall with a riot of faces and colors. The paintings, collages and mixed-media works are the product of a diverse group of young people, aged 10 to 17, black and white, from rural, suburban and urban communities. The group was drawn together by the Mississippi Young Person's Cultural Exchange Program, a two-year collaboration between four social-service and arts organizations: the Madison County Cultural Center, Operation Shoestring in Jackson, Moore Community House in Biloxi and Mississippi Cultural Crossroads in Port Gibson.

The Mississippi YPCEP originated with a Mississippi Cultural Crossroads pilot program from 1994-1995. Patty Crosby, an artist and executive director of Cultural Crossroads, says the pilot program opened up the creative process to her students, making conversation and reflection an integral part of making art.

"I just found (that) asking the kids after they finished their particular piece of artwork to talk about it gave us incredible insight to the kids themselves and what they were thinking about when they did it," Crosby says.

Based on that initial success, Crosby solicited participants for a statewide program in 1998. The program began in earnest in January 2000, with adult artists and community members leading students in discussions and guided activities based on nine different themes: What Makes Me?, Family and Friends, Place and Neighborhood, Food, Celebration and Spirituality, School and Work, Play and Recreation, Sickness and Healing and Past, Present and Future. Program leaders exchanged art between the different sites, using the work of a different community as a starting point for more conversation and art.

While these themes served to ground the children's art, the program leaders were careful not to impose adult notions of art's definition or meaning on the young artists. As in the pilot program, they asked students to write a brief note about each piece they finished. The exhibit displays these notes, along with the theme they address, on each work's label.

The notes capture each artist's voice, giving a sense of the personality behind the works. Sometimes that voice is matter-of-fact, as in a self-portrait by LaShawndria Monroe, which bears the note, "This is a picture of me. This day, I had my hair up in a ponytail with a purple bow in it. I think I had a good-hair-day that day." Other times, it is exuberant, as in Kristen Kyles' large watercolor of a Pop Tart, whose label simply declares, "I am in love with Pop Tarts."

In some cases, the voice provides a counterpoint to the subject matter. "Salt Treatment," a drawing by Joseph Marquez, is a stark depiction of a child's wounded arm, with another poised above it, shaking salt onto the cut. His note reads, "When I am hurt my dad puts salt on my wounds to make them heal." The straight-faced tone of the caption echoes the drawing's clinical composition: just the two arms, extended into blank space. The drawing leaves out any sense of pain, excluding the faces and bodies of father and son.

One of the most striking things about the exhibit is something that's not visible. The class and cultural boundaries that the program sought to cross appear, if at all, in a subdued manner. There are some notable exceptions, such as a quietly powerful drawing of segregated water fountains, but for the most part, the children's art tends not to dwell on inequality or difference.

The lack of such serious subject matter does not mean the children were unaware of it, though. "By and large, when you ask children, who are pretty optimistic in general, to talk about and draw these topics, they talk from hopes," Crosby says.

Crosby calls the Mississippi YPCEP, which ended in 2001, "a life-changing way to do art with children." In the years since the program ended, participants' lives have changed as well. Hurricane Katrina destroyed the program's art at Moore Community House. Many of the children have since graduated from high school; one is even finishing law school this summer.

While the exhibit presents the seemingly universal optimism and exuberance of youth, it is also a document of individual young people, and it is their relationship between the general and the specific that makes the exhibit so compelling.