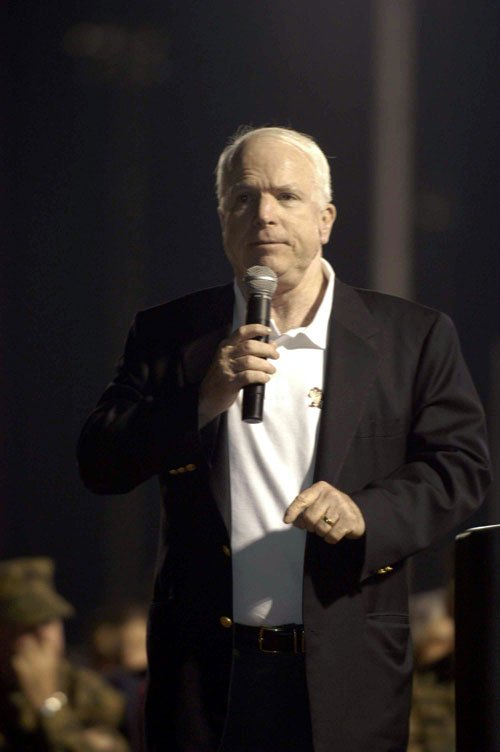

Perhaps one of the more effective openings that Sen. Barack Obama has had for criticizing his opponent, Sen. John McCain, has been in the contrast of their health-care policies. Obama and his campaign have pointed to a part of McCain's plan that will tax health benefits offered to you by your employer, with apparently effective results.

According to an analysis by the Tax Policy Center (taxpolicycenter.com), with the McCain plan, your increased tax burden would generally be offset by the tax credit ($2,500 for individuals, $5,000 for families), assuming the health-care premiums fall under those caps. If your company continues to provide benefits, then the likelihood is that they would be taxed on your returns at less than the credit; if your company doesn't offer benefits, you'd have a small tax credit to apply toward a personal policy.

Unfortunately, whether your premiums fall under the tax credit cap is a big "if." Individual policies tend to be considerably more expensive than company-based policies, and policies for at-risk patients can be astronomical on the open market.

And if you do stick with your company plan because it's comprehensive, that new taxable income could not only be a greater burden than the tax credit, but also, the additional reported income could even send you into a new tax bracket. The end result: Companies will stop offering health-care plans as a perk because they increase the employee's taxable wages. You'll probably just ask them for the cash, instead.

In a perfect world, this would be an intriguing approach, as it could potentially increase access for some classes of workers. (And some form of this plan might be wise for Obama to adopt specifically for contract and self-employed workers.) But, in this imperfect world, access isn't the only problem.

Obama's plan is the more comprehensive choice, if only because it promises an effort to reform the current system. Access to insurance isn't the only problem; the way the insurance companies assess risks, fail to pay claims or fail to ensure procedures are also key issues.

Under the Obama plan, health-care providers can still make good money for offering innovative, effective services; insurance companies, however, will be watched much more closely for exactly how and why they derive their profits. Likewise, the Obama plan encourages more coverage through employment, including credits for small business that offer health care to employees.

Arguably, aspects of the McCain plan could be enacted either simultaneous to the Obama plan or after key insurance and provider reforms have been put into place. But until that happens, injecting more individuals into the marketplace for insurance policies won't solve the current crisis.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus