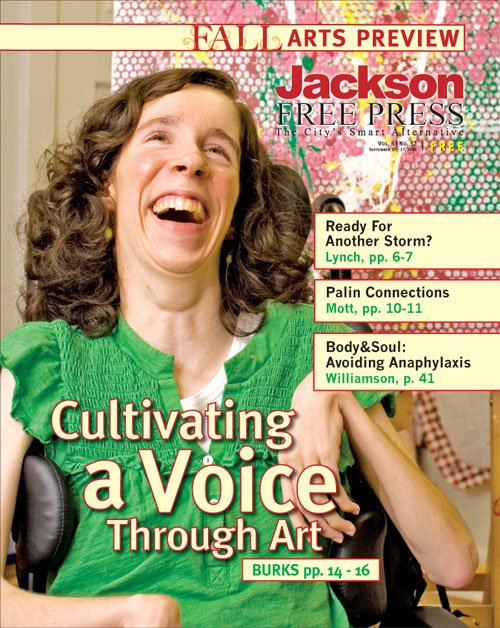

Filtered sunlight streams through the windows of Claire Myers' studio on Thursday morning in Jackson as she waits to begin painting, something she does twice a week. Gray clouds linger in the sky from a recent storm but there's just enough light spilling into the room to illuminate Myers' dangling yellow earrings, which peek through her wavy dark hair. Leaning back in her chair, the 21-year-old artist ponders which canvas to paint.

"Which one do you want to use, Claire?" asks Latanya Harris, gesturing to two canvases, one in either arm. Harris, 30, is a direct support professional from Oxford Home Health Services and has worked with the Myers family for five months. "You want to use this one?" she asks, holding up the 18-inch-by-24-inch canvas. Myers motions affirmatively, and Harris places the larger one in a corner for another day.

As she affixes the canvas to a wooden easel, Myers' mother, Charlotte, detaches her daughter's speaking device from her wheelchair and sets it on the tiled floor next to her. The device, the Pathfinder, is a tool specially designed to help people with limited verbalization communicate; only Claire won't be using it today. She now has another way to express herselfthrough her art.

Myers has cerebral palsy, a condition that limited her verbal capability and took most functionality of her hands at birth. Art classes at Ridgeland High School piqued Myers' interest, and she soon developed a love for painting. Her instructors made art accessible to Myers, but Charlotte set out to make it something she could create.

"This is the only method I know of for artists that cannot use their hands," Charlotte Myers says of Tim Lefens' technique, which she learned at a workshop in Starkville. Lefens, of New Jersey, developed the method to include the use of a trackersomeone who works as the arms and hands of the artist. Charlotte has been Claire's tracker since they began using the technique in 2004. Harris has been training as a tracker for five months.

Using a "yes/no" system, Myers has full creative control over her work as the tracker refers every decision to her. Myers looks upwardand sometimes smilesto indicate "yes," and buries her chin to her chest for "no." She also gazes toward an option she wishes to choose, like the canvas. Whether it be deciding the orientation of the canvas to mixing colors, the tracker eliminates his or her opinion and acts solely as an extension of Myers.

"You have to be patient; you can't interject your opinion," Charlotte Myers says of tracking. "We just do what she tells us to do. This is truly her work, not the tracker's."

Once the easel is situated, Myers indicates that she wants to section off parts of the canvas. Harris moves across the canvas with a yardstick, and Myers indicates where she should stop it and make a marking. Harris and Charlotte Myers lay blue painting tape across the specified marks. The result creates several triangular shapes on the canvas. Charlotte Myers then presents Myers with a color chart. The chart has 12 colors painted on it, each with a number below. That number corresponds to a bottle of Blick acrylic paint. Myers selects red, and her mother asks if she would like to add another color to it. She gazes upward, and the two go through the color chart again.

"One of her main strengths is color," Charlotte Myers says. "She has a really good color sense and makes a lot of interesting color combinations."

Charlotte Myers and her husband Don, a dentist and an instructor of anatomy and physiology at Hinds Community College, make a joint effort to support Myers' work. Don Myers tracks sometimes, and he builds the canvas frames. He also acts as Myers' business manager. "He's a pretty good business manager, isn't he, Claire?" Charlotte Myers asks playfully, stopping a moment to gaze back at Claire as she paints. "Do you get him to do anything you want?"

Myers grins and laughs, nodding her head back in agreement.

At lunchtime, the canvas has lilac and rose-colored sections, and a couple left to paint. The three women break for lunch and head down the hall toward the smell of spaghetti. Myers' studio, which she shares with students, is located in the Privette School at Broadmeadow United Methodist Church. Charlotte Myers calls it a perfect fit.

Horses, Children and Art

After Myers graduated from Ridgeland High School last May, her family began looking for a place where she could paint regularly. Her family didn't want Myers to work in a secluded studio or not be able to interact with people, but they weren't sure what was out there. Myers' cousin, Chris Brooking Richardson, went to divinity school at Duke University with Broadmeadow's senior pastor, Rob Hill, and asked him if he knew of such a place.

"I think I've got a space for you," Hill told her.

The school had just finished renovating the Lanita H. Pittman Children's Art Studio, and Hill knew that there would be times when it would be empty. He also thought it would be a good idea for the children to interact with Myers.

"We're obviously teaching them a lot of things here, but we're teaching them about life," Hill says. "What a wonderful way to experience life in seeing someone like Claire who is in a wheelchair and is unable to do things the way others areand here she is being a full-time artist. 'They could learn a lot from Claire,' is what I thought."

The Privette Schoola private day school for children under 4uses the Reggio Emilia Approach to learning, which focuses much of its instruction on art. In the studio that Myers shares with the students, art projects and supplies line the counters and walls: painted egg shells, Jell-O paintings, construction paper cutouts, birdseed canisters and more. They fit in well with Myers' unconventional tools, such as bubble wrap, loofahs and sponges. Hill marvels at the interaction between the 3- and 4-year-old students and Myers on their first encounter.

"None of them had any questions about the chair. They were more concerned that Claire had not had breakfast that morning," Hill says. "They didn't ask about why she was in her chair, why she wasn't able to use her hands the way they were able to use their hands. In fact, they were going up to her and touching her hands and touching her chair, but not asking questions."

After a while though, the questions came, and some children had unique answers. "Why can't she walk?" one student asked Charlotte Myers when a class of toddlers visited the studio. "Because she needs a new battery," a boy, Charlie, answered.

"The boys like Claire's wheels in particular," one of the teachers says, speculating on why only the boys ask Myers questions.

As Myers paints, a teacher wheels three doe-eyed 6-week-old babies in a Radio Flyer wagon up to the studio door. "Claire, you want to see some of your friends?" Charlotte Myers asks. Myers' arches her back, looking upward, smiling, and letting out a deep moan of excitement. They visit for a moment, then the teacher whisks the babies away for nap time. Myers' smile lingers.

"We were exploring her strengths and weaknesses at school andit's amazing to me when I look backfor years, she's always said that her favorite things are horses and art and young children," Charlotte Myers says. "It's amazing to me how all this fell into place."

ArtShare

Eleven years ago, Myers met Hannah Southerland at a camp for augmentative communication users at the T.K. Martin Center on the campus of Mississippi State University. Myers was 10 and Southerland was 4. Although Southerland lives in Monticello, Miss., the two remained good friends, and when Myers learned Lefens' technique in 2004, they began

a tradition.

"When Claire learned this technique, I thought Hannah just might like it, too. So we invited her to just come and watch Claire, and she just fell in love with it," Charlotte Myers says.

In September 2007 Myers and Southerland began meeting one Saturday a month to paint, often taking a break in the afternoon to shop and go out to eat, before returning to paint more.

The LifeShare Foundation offered them the LifeShare house on the campus of the Mississippi School for the Deaf and Blind to use as their collective art space. The foundation is a private non-profit organization that seeks to meet the needs of at-risk or underprivileged children in Mississippi. Built in 2000, the LifeShare house is "like the Ronald McDonald House" for parents of students at the School for the Deaf and Blind, according to Bob Crisler, LifeShare director of assistive technology.

Crisler had known the Myers family from the time Claire began doing a work study-type program in high school at the LifeShare Foundation. Claire acted as a test subject for Crisler's latest software development project for people with limited verbalization. It was Crisler who suggested Myers use the LifeShare house as a weekend painting studio, and after seeing her work, he encouraged Myers to make her passion into her profession.

"Charlotte showed me (Myers' work) and I said, 'Well, Charlotte, this would be a great job that Claire could create for herself when school is out. What an inspiration that can be to other people to see somebody doing something that you don't really think they can do. But she does it, and does a fine job of it. And that was really the beginning of ArtShare," Crisler says.

It wasn't long before Katy Anderson, another student with limited verbalization from Greenville, joined in on the Saturday painting sessions. Charlotte Myers taught the other mothers how to track their daughters' work, and each artist began to develop their own voice through their pieces.

"It's fun," Charlotte Myers says. "It instills confidence, and they learn from each otherthey love to watch what the other one is doing, sometimes almost too muchand they just enjoy being together. They interpret things through their work."

In March 2008, Crisler approached the Mississippi Arts Center with the three artists' work, and on Sunday, Sept. 7, "ArtShareThree Artists" opened in the upper atrium of the center.

'Get To Work'

Red dots marked the captions of most of Myers' paintings at the exhibit's opening reception. During the first two hours of the show, she had already sold nine canvases. The first piece she ever painted, "One," displays a fire-engine-red background with color splotches across the upper left corner of the canvas. One lone white strip of paint runs diagonally from left to right, contrasting the chaotic greens and blues of the other splotches. Upon seeing it, several people pleaded with Don and Charlotte Myers to sell it, but it was not for sale.

While several people were interested in Southerland's work, she was apprehensive at first about letting her work go. "After she met the woman buying the piece, she was OK with it," her mother Tina Southerland said at the reception. The woman who bought the piece was Mary Kitchens, Don Myers' cousin. "She kind of put a face with the purchase, so I think that helped," Charlotte Myers says.

Myers and Southerland painted two of the pieces hanging in the exhibit together.

After wandering in and out of the exhibition rooms, Myers' grandmother, 85-year-old Helen Putnam, stops in front of one of her granddaughter's paintings, which a man is admiring from nearby. "I'm the artist's grandmother," she tells him proudly. Putnam explains to him that art is in Myers' genes.

Myers' great-grandmother was an artist and seamstress; her grandfather was a sign painter; her aunt, Sharon Grinspan, is a mixed-media artist and photographer; Charlotte Myers did interior design; and Putnam was a calligrapher and graphic artist for the Memphis Commercial Appeal.

"I always worked in black-and-white, working for the newspaper, and now look at what she has done with color," Putnam marvels, raising her index finger to "One."

Looking around the room at all the red "for sale" stickers, Charlotte Myers sighs. "We've got to get to work," she says to Claire, smiling.

"ArtShareThree Artists" will hang in the main gallery of the Arts Center of Mississippi (201 E. Pascagoula St.) through Oct. 3. Admission is free; call 601-960-1557 for more information.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus