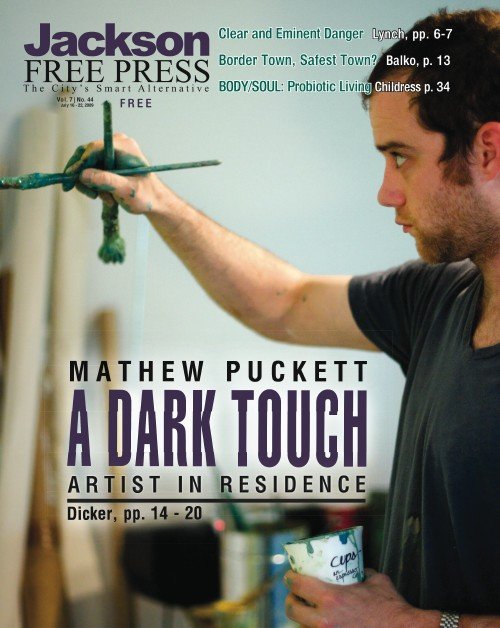

Mathew Puckett's workspace on the second floor of One to One Studio is full of oil paintings of variations on his image. There's the one of him in profile sitting in a wooden armchair, a small figure staring into an empty room. There's the close-up of him in a T-shirt, framed by a bright blue sky and marbled clouds and looking off to the side. More notably, there's the 8-foot-by-4-foot nude figure looking straight ahead, his thin body painted from the waist up and literally larger than life.

"It's not important that they're me. ... It's just painting out of convenience because I'm always here," he says with a laugh. "And it's hard to find somebody who will sit for you for a few hours every day." He says that he prefers painting in the mirror to working from a photograph.

Puckett, a 29-year-old Jackson native, seems to accept life's paradoxes. While he is relatively new to the professional art scene, he is already receiving the accolades of a seasoned painter. Although he appreciates the increasing attention he is getting for his two major upcoming showsone at the Mississippi Museum of Art and another at Fischer Gallerieshe isn't quite comfortable with it, yet.

Marlboros and Mumbles

"I tend to mumble," Puckett warns me as we sit down in his studio on a humid Wednesday morning in late June. He's not exaggerating. He speaks from the back of his throat, in a soft Southern drawl that's easily drowned out by the whirring of the small air conditioner in the corner of the studio.

After a couple of minutes, Puckett reaches down from the rusty metal stool he's sitting on and grabs a pack of Marlboros from the concrete floor.

"Mind if I smoke?" he asks.

"I'm not a huge fan," I tell him, laughing uncomfortably. "Thanks for asking."

He smiles and nods, as if it's not a big deal, and tosses the pack back onto the floor, which is splattered with colored paint and littered with dozens of items: an open toolbox, scattered tubes of oil paint and even his keys. He says that while it's messy, he notices when someone has come in and moved something.

As we begin talking, I can sense that he would be more at ease with a cigarette. I tell him to go ahead. He picks up the pack, lights up, and turns slightly away from me to divert the smoke.

"I'm still getting used to getting attention for my artwork and being approached about it," he says, scratching the back of his curly head with the hand holding the cigarette. "It's pretty new to me. The Invitational made a big difference."

Last December, Puckett applied for The Mississippi Museum of Art's 2009 Mississippi Invitational, which showcases recent work by visual artists who live and work across the state. Every other year, the museum showcases the work of artists who show exceptional talent and diversity in their work.

This spring, Peter Plagens, an internationally known art critic for Newsweek, judged the Invitational and visited the 15 finalists, including Puckett, in their studios. Soon afterward, Plagens selected Puckett as one of the 10 artists included in the Invitational show.

Puckett will display several of his paintings at the Mississippi Museum of Art from Aug. 1 through Nov. 29 as part of the seventh Invitational.

That same week, on Thursday, Aug. 6, Puckett has another show opening at Fischer Galleries in Fondren. His paintings will be the main attraction, accompanied by the portrait sculptures of artist Stacey Johnson.

Puckett slouches and rubs his eyes, which look a little bleary. In order to prepare for the show at Fischer, he's been in the studio as much as possible over the last few months.

"I tend to work really slow. So I have to be working a lot, otherwise I won't get anything done," he says, sipping a mug of coffee. "Normally it would take me, probably, between eight and 10 months to get that much work done, so I'm trying to squeeze it into three or four months." Fortunately, he had completed the pieces for the Invitational before the application deadline last year, so he can focus on preparing for the Fischer show.

"The work I'm doing for the (Fischer Galleries) show, I think it's the first time I've done a real series," Puckett says. He says that while he's always wanted to do one, he hasn't been settled enough to focus on one theme.

"I like working this way, because at the beginning of each painting there aren't as many questions," he says. "I know what colors to use, and what kind of space I want to make."

Puckett's paintings for the Fischer series are of lone figures in rooms with blue and green walls formed from strong lines.

"I don't think I've ever done a painting with more than one person," he says. "Putting a second figure in automatically adds another psychological dimension." He expects that he'll begin to include multiple figures or other objects into paintings in the future, but he hasn't felt a need to do so, yet.

"For things that I'm trying to get at now, one figure does the job," he says. "Some sort of tension, whether it be between the figure and the ground, or between the surface and the space."

Puckett's figures tend to be small compared to their surroundings.

"Do you see themes of isolation in your paintings?" I ask.

"I was thinking about that," he says, "because I think it's something a lot of people see." He says that he gives less attention to how the figure is feeling than to its relationship with its environment, and to the color and composition of the painting.

"It's the viewer's job to put the psychology into it," he says, smiling.

Picking it Apart

A shy child, Puckett kept to himself and spent a lot of time figuring out how the things around him worked.

"I'd just take everything apart," he says. "Whatever was around melike a remote control ... just to see how it worked. Even a plant, I'd open it up and see what was in there." His parents didn't mind, he says.

"I'm just curious about things. I want to know why," he says. "My girlfriend always makes fun of me, because I'm like, 'Why is this happening? Why is this? Why is that?' It can be people's motivations, or how something's madelike a piece of furniture."

Puckett went to St. Andrew's Episcopal School from kindergarten through 12th grade. Although he always liked art, he was "not like Picasso"that is, he didn't have an especially prodigious interest or skill in the subject. He does remember one colored pencil drawing from high school, a doodle that turned into a more complex pattern, which a friend told him was exceptionally good.

Puckett's parents, neither of whom are artists, supported him in whatever he chose to do and trusted him to make his own decisions. They divorced when he was in fourth grade, but he remains close to both of them.

"In high school, I had terrible grades and just didn't do any work," he says. "I think I was just lazy. So, you know, they weren't real excited about that, but they didn't give me too hard a time either."

He skipped school to do art or hang out with his friends, especially in his junior and senior years.

"We were always in trouble," says classmate Josh Hailey. "We were artistic troublemakers, but nothing that a couple of detentions or suspensions couldn't handle."

Early on, Puckett became friends with Hailey and William Goodman, who were both in his class at St. Andrew's. All three became well-known Jackson artists, and their classmate Douglas Panzone is an acclaimed graffiti artist in Charleston, S.C.

Hailey says that the 60 students in his and Puckett's class "all came out to be either doctors, lawyers or art majors."

St. Andrew's had a culture that nurtured artistic development from an early age Hailey says. Students took art classes each year, and the "eccentric" teachers at St. Andrew's "pushed us to see abstract stuff when we were real young."

Mrs. Mitchell in particular, who Hailey says was around 3 feet tall and wore muumuus every day, "was just the best art teacher ever."

"She let us do everything and anything we wanted," says Hailey. He and Puckett, along with their classmates, had a chance to experiment with different mediums in Mrs. Mitchell's class like photography, sculpture and painting, and different arts like theater.

"I always thought Puckett would come out as a writer," says Hailey. "He's ridiculously intelligent. ... He knows a little something about everything." Away from Jackson and Back

After graduating from St. Andrew's in 1999, Puckett didn't want to go to college right away. Instead, he moved to North Carolina, where a good friend lived.

"I think I was the only person in my graduating class who was undecided about my future," he says.

He began doing maintenance work for the company that managed his apartment complex, and for a five-star restaurant called Crippen's. He came in once a weekon the day that it was closedto maintain the kitchen equipment. He was allowed to cook just about whatever he wanted to, except for the expensive foods like filets and lobsters.

After six months or so, in the spring of 2000, Puckett decided to enroll in the University of Southern Mississippi because he felt that he needed some direction. After a semester, he transferred to Ole Miss, where he remained for a year.

"I didn't really get anywhere when I was in Oxford," he says. "I'd just go to class, then go to work, then just come home."

After staying another semester to work in a bakery, Puckett ended up back at USM. He doesn't know exactly why he went back and forth between colleges. His early 20s are fuzzy in his memory.

"I think I was just kind of aimless," he says.

Eventually, Puckett left school altogether and moved back to Jackson.

"School wasn't doing anything for me," he says. "Really, after that semester, I didn't expect to go back. I didn't really like school."

Puckett started working for restaurant owners Tim Glenn and his son, Nathan, baking bread for Rooster's, Basil's and The Auditorium.

Nathan Glenn says that Puckett understands the delicate balance of ingredients that go into good quality bread and has the patience to work with them. "Probably some of the same qualities that show up in his art, show up in his bread," Glenn says. "He's actually one of the only artisan bakers I've ever met. He's mostly self-taught."

Glenn says that Puckett, one of his best bakers, will still fill in at the restaurants occasionally, particularly to train new employees. He describes Puckett as the tortoise from the fable "The Tortoise and the Hare."

"He's kind of laid back," Glenn says, "but he's always going to finish ahead of everybody else, and it's gonna be better, and more efficient."

After a few years of working in the restaurant business, at age 25, Puckett began talking with the Glenns about collaborating with them, possibly opening a restaurant in the future. He decided that he could develop his business skills in school, so he enrolled at Millsaps as a business major. He thought he would give school "one last try."

"I had no intention of doing art," Puckett says.

He took a painting class as an elective, and there he realized that he didn't want to go into business. He liked the physical act of creation too much. He changed his major to art.

"Food and paintings are material things. ... There's a lot of touch involved," he says. "Above any kind of intellectual response (to my paintings), I want the first response to be a visceral sense, almost a physical feeling."

Today, Puckett thinks it was helpful for him to wait until he was older to choose what he would study. Whereas his younger classmates at Millsaps were still exploring what they wanted to do, he made the decision more quickly.

Although Puckett says that "it's kind of strange talking about my work, and art in general," he thinks that Millsaps taught him how to do it effectively. Within the course of a given hour, he'll quote the likes of Da Vinci and Mark Rothko, and refer to the art of William de Kooning and Kandinsky. The bookshelves in his studio are lined with his art textbooks, which Puckett refers to when he needs inspiration or guidance from the masters.

"Emerson said that reading is for the dark times, when you don't know what else to write," Puckett says. He believes it's the same with painting.

Finding a Routine

Shortly after graduating from Millsaps last spring, Puckett began renting his studio space at One to One Studio and became a full-time painter.

Every morning on the way to the studio, Puckett picks up an espresso at Sneaky Beans in a paper cup that he rinses out and uses as a container for paint. He likes to drink a couple bottles of San Pellegrino sparkling water per day. From the looks of the cardboard box on the floor, which is brimming with green bottles, he's had this routine for some time now.

Puckett points out that both espresso and Pellegrino are Italian. "That's funny, I never really realized that until just now," he says.

"Have you been to Italy?" I ask.

"Yeah," he says. "I spent most of my time in Rome. That city is kind of a museum in itself. If you want to go see Caravaggios, you just walk around and just find Caravaggios and Berninis everywhere."

Puckett keeps to a fairly regular schedule, which he says disciplines him out of his lazy tendencies.

"When it wasn't so hot outside, I really liked to get into the studio about 9, stay until lunch and then go and eat sushi," he said. "Then I'd go on back until 6 or 7, and then I'd go home and cook dinner. Those days always felt real good. I'd get a lot done, and then eat good food."

Now that summer's heat is warming up his second-floor studiodespite the air from the big fansPuckett gets in as early as he can and leaves by 1 p.m. While the reduced schedule has limited the time he can paint and sends him home exhausted, he says that it has also helped him create more structure.

Puckett says that he normally comes into the studio every day for at least a little while, even on weekends.

"I start getting antsy and irritable if I don't come in here," he says. "If I was to not come in for a week or something, I feel like I come back in and I don't know what I'm doing. Like I don't how to paint anymore," he says. Although he still has the technical skills, he says, he loses touch with his creative intuition if he doesn't use it regularly.

Puckett steps over the mess on his floor as he talks, walking over to a table against the wall. He's put a sheet of glass on top of it, but it's impossible to see under the thick splotches of paint, various paint-covered cups and containers and brushes, and a wayward stack of CDs.

There's a small boom box in the corner that's playing Tom Waits' soundtrack to "Night on Earth." Puckett usually listens to music while he paints, which keeps him company in the empty studio. While he shares the space with artists Robyn Jayne Henderson and Shambe Jones, they keep different hours.

Puckett seems to prefer folk music with meaningful lyrics and a melancholy sound: Waits, Leonard Cohen, Nick Cave and Cat Power. He says that while he's painting, he's "not thinking lighthearted thoughts." Translating an idea to a physical form is an intense process.

"The paintings aren't that important, really," he says. "They're just the result of that (idea)."

Oil painting can be a slow process, because the paint takes so long to dry, he says. He'll work on a painting day after day until he's satisfied that he's captured a complete idea. A painting is finished, he says, "when it becomes what it is, not necessarily what you intend it to be."

Philosophy and Art

At some point during his studies at USM and Ole Miss, Puckett became a physics major. He wasn't any more diligent about schoolwork than he had been in high school, but he would read books like "The Elegant Universe" and "In Search of Schrödinger's Cat" at home. Both art and physics, he says, are trying to capture the intangible and understand the world through exploration.

"Ideas will bend to something physical most of the time," Puckett says. He believes that he's getting better at translating his idea to the canvas but still likes the mystery involved in art: how a particular blend of paint will behave on the canvas and what image will ultimately emerge.

Puckett says that he'd rather his paintings raise questions for people than make a statement of any kind. "I think a lot of the asking 'why' is more just kind of posing the question," he says. "A lot of the time, it's more important to think about it than to actually know. I don't want everybody to come away from (my paintings) with the same conclusion, if there is a conclusion."

He'd rather inspire curiosity in his viewers, and have them wonder about elements of the painting, and why they look a certain way. For this reason, he tends to use loose brush strokes, to blur the lines between figure and ground.

Puckett points to one of his paintings. "If you look at it really closely, it just looks like drips of paint," he says. "It doesn't look like there's any form to it, which is something I like. I like that if you look at it really closely, you're not going to be able to see what it is. And then it's only paint at that point. If you look at it further away, it becomes something.

'What's In His Head?'

Exactly one week after our first meeting, I'm back in Puckett's studio. The picture he'd been finishing, modeled on a photo of his girlfriend, is now propped up against the others on the west side of the room. A blank canvas now hangs on the wall, on which he has sketched in pencil a pair of vertical rectangles and a series of zigzag horizontal lines.

This time, I ask Puckett to paint while we talk, and he seems more comfortable. Not only is he able to move around the room freely, but he is also able to use the precious morning hours to work on the Fischer Galleries series.

As he talks to me, Puckett mixes green and white paint with linseed oil in a paper cup and thins it with turpentine. He loads a thick brush with paint and begins swiping up and down on the upper left corner of the canvas. I have to lean in to hear him, because he's projecting his low voice toward the canvas and swishing loudly with his brush. Now and then, he steps back to look at the painting from a distance. He walks over to the couch to punch a text message into his cell phone with one finger, so as not to cover the device in paint.

A half-hour into our talk, the door of the studio opens, and Marcy Nessel, the owner of Fischer Galleries, walks in with a smile on her face. It quickly becomes clear that Nessel is the type who rarely doesn't smile. She says most things with a bubbly laugh so contagious that it's impossible not to laugh yourself. At first, Puckett says, he wasn't sure if she was really that cheerful all the time, but over time he's come to realize that she is.

Nessel seems to bring out the lighter side of Puckett, who tends to be serious, at least about his work. When she's around, her positive energy almost palpable, Puckett's eyes brighten and he smiles more than usual.

Dressed in fitted linen pants and a stylish belt that shows off her slim figure, Nessel has stopped by to see Puckett's paintings, some of which she hasn't seen, yet.

She walks around the studio, starting on one side where Puckett has hung a couple of paintings on the wall.

"That's looking great!" she says with a huge grin, cooing over one of them.

She examines a smaller canvas on an easel, featuring a seated, faceless figure and a color palette of dramatic blacks and reds. Two blank canvases lie on the ground beneath it.

"That's a little darker!" she says. "This is the triptych?"

Puckett nods. Nessel pauses, taking it in.

"Huh!" she laughs, finally, as if she's not sure what to make of it.

"Yeah, it's a little weird," he says.

Puckett follows Nessel to the other side of the studio, where several large canvases are propped up against the wall, one on top of the other. Nessel looks at the painting in front, the one of Mathew in profile in the chair.

"Oh, I love it!" she says. She pulls the canvas forward to see the one behind it, a portrait of an older man staring straight ahead. It's one of the few paintings that Puckett has modeled on someone elsehis stepfatherand not on his own reflection in the mirror. The man's face is beet red against the tan background. Nessel squeals and giggles.

"Ok, I have to say that the background of the painting is" She pauses. "I love it, I love it, I love it." Nessel turns to me. "His background is a painting within itself," she says. "It's this great montage of paint and form and interesting design layout. Look at the simplicity of the background, in contrast to the intensity of the face. His work causes you to think, 'What's in his head? What's going on with this guy?'"

Discovering Fischer

Puckett met Nessel long ago through his parents, who have known her for more than 25 years, but he didn't know her well until she opened Fischer Galleries in Fondren in November 2008.

"I went into her place the opening night, and I thought, 'This is it. This is the place I want to show.' He liked all of the pieces in the gallery, including those of his friends Ginger Williams, William Goodman and Baxter Knowlton.

Nessel remembers that Puckett stopped by the next day. "He said, 'I'm painting, and I really think that my work would show well in the gallery.'"

Nessel invited him to bring over some of his work. He did, and she knew right away that she wanted to represent him at Fischer. Instead of the landscapes or abstracts more common to Mississippi painters, Puckett painted human figures in a style that Nessel compares to the work of the masters.

Nessel points to what is probably Puckett's best-known painting, a large nude. "When Puckett completed this," she says, "we hung it in the gallery, in this spot where you could see it through the doors at night. We put a light on it at night, and I would have people who would come by the next morning and say (gasps and puts her hand to her chest) 'We drove by, and I've got to see that painting.' It's so striking."

As a gallery owner, Nessel promotes Puckett's show through press releases and mailed announcements. "What I try to do is get him out there," she says, "get his name recognized in the community, which"

"It's going pretty well," Puckett interrupts, with a laugh. Nessel laughs, too. Both are aware that with two shows opening in August, his reputation as an artist is growing quickly. Puckett was recently filmed, along with Hailey, for a feature on Mississippi Public Broadcasting's "Southern Expressions." The weekly television program spotlights artists in the state, interviewing them about their work and capturing them in the studio. Puckett's episode will air on MPB later this year.

After Nessel leaves to head back to the gallery, I ask Puckett how he feels about her seeing his work for the first time.

"It's already done, so I know I'm not going to go back and paint on it anymore," he says, adding that the limited time before the opening wouldn't allow it anyway.

Nessel has been very supportive, Puckett says. "She seems to like my work, so I don't worry about it much."

'Something You Do'

In August, Puckett will start a two-year master's of fine arts program at the Memphis College of Art. Of the school's 320-member student body, about 14 are MFA candidates. Puckett estimates that nine of these 14 have a studio art emphasis like he does. Having gone to a small school growing up and having graduated from Millsaps, he chose a small art college over a large university.

Before visiting a handful of colleges, like the Savannah College of Art and Design and the University of Memphis, Puckett researched some of the big names online, like Yale and Columbia. While he was blown away by the well-known, high-caliber faculty, he couldn't justify the price tag.

"I just don't see going $90,000 into debt to come out and be like, 'I'm a painter!'" he says, raising his voice an octave and waving his hands in the air. "I don't know if I'd be able to make it just paying rent, let alone paying off those student loans."

He says that while the networking and exposure at big-name schools might help accelerate his career, he feels that it's most important to be at a school where he felt comfortable and would make progress with his art.

"I'm going to the school to learn something," Puckett says. "It's not really much about the degree. Although that'll help if I want to teach someday, which I think I probably will. Even if I'm super successful, I still feel like I'd want to teach."

A couple of schools, SCAD in particular, were not a good fit, although he respected the work of the professors.

"There are too many art-school kids there, in their art-school-kid uniforms," he says. "You know, with their dyed hair that's gelled up and stuff. They all look the same. It seemed like, for a lot of them, it was more like being 'on the scene,' or something like that. Like an artist was something to be, rather than art being something you do."

Having had the chance to explore different art forms in his undergraduate art program, Puckett hopes to hone his craft in graduate school.

"You're already expected to be good at whatever you do, whether it be painting, or sculpture, or whatever, and have a particularly substantial knowledge base about it," he says. "Grad school, I think, is more about developing what you do, and developing your ideas and how you translate those into physical things."

An Unclear Future

After art school, Puckett isn't sure what's next. "I think it depends on what happens during art school," he says. "Hopefully it'll be a really dynamic two years and a whole lot will happen, just as far as what I learn how to do."

No matter where his art takes him, Puckett expects that he'll come back to Jackson, whether right after graduating or 10 years down the line.

"Jackson's a good place to live for an artist. Living is pretty cheap here, and the way things are now, if you get enough connections and get in enough galleries or publications, you don't really have to live in New York or Chicago. You can live here for cheap and make work here, and send it (elsewhere)."

"So far, if I can pay my bills and if I feel like I'm progressing, I think that's pretty good. As long as I feel like I'm learning something and making some kind of improvement, I think that's pretty good."

Puckett has just begun to sell his paintings and is already getting recognition for them. He's glad that Fischer Galleries is in Fondren, a hub for the arts community where he hangs out with his old friends Hailey and Goodman, as well as other artists like Williams, Knowlton and Twiggy. He says it is not intentional that he's friends with a lot of artists.

"Most of them I've known not really as artists, just who they are," he says, adding that he's been friends with them since he was young. "I feel real fortunate. I don't think that happens very often."

'Blank'

Two weeks after our first meeting, Puckett and I meet inside Sneaky Beans café. He seems more relaxed than he had in the studio. He leans back against the wall behind him, holding a near-empty paper cup of coffee.

"I had a messy day today," holding up hands with residual blue and green paint on them. As he talks, Puckett fiddles absentmindedly with his surroundings, with the swivel chair behind him, or with his phone when it sounds to announce a text message.

"How do you feel about being interviewed in such depth?" I finally ask him.

"I don't know, I guess I'm just not used to it, so it's kinda weird," he says. It's just strange knowing that it's going to be published."

"It's not that it's been like" he pauses.

"Torture?" I ask.

"Yeah, it's not that it's been like that. It is really weird talking about myself, you know, but it's actually better than I thought it would be."

Hoping to give him a break from trying to describe in great detail what he knows he can never satisfactorily describe, I end our last interview with simple word associations.

"I'll give you a word, and tell me the first thing that comes to mind," I say. He nods in agreement.

Paint, I say.

"Mud," Puckett says.

The past.

"Rich."

Jackson.

"Home."

Fame.

He pauses, then shrugs.

The future.

"Blank," Puckett says.

The Mississippi Museum of Art's 2009 Mississippi Invitational show runs from Aug. 1-Nov. 29. Museum members only are invited to attend an opening reception on Thursday, July 30, from 5:30-7:30 p.m. The Fischer Galleries show opens on Aug. 6, with a reception 5-8 p.m. which Puckett will attend. The show ends Aug. 20.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.