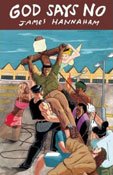

James Hannaham's novel "God Says No" (McSweeney's, 2009, $22) chronicles the coming-of-age of Gary Gray, a man who loves Jesus and Disney World in almost equal measures. But he loves his college roommate, Russ, almost as much as he loves Christ, and not at all in the same way. For an overweight black man dreaming of the Christian life in Orlando, that dormant homosexuality is a lit firecracker ready to go off in his hands.

As he moves from college to marriage to fatherhood, Gray seesaws between his Christianity and his homosexuality. He loves his wife but isn't attracted to her. He loves his daughter but spends more and more non-working hours away from her, getting laid by men in public restrooms and pit stops. He loves Christ but can't walk away from what he thinks Christ condemns.

Gray thinks, wrongly, of his sexual orientation as a costume that he can learn to take off at will. So, when he survives a train wreck in rural Georgia, he sees it as divine intervention. Gray convinces himself that God's given him a chance to go to Atlanta and "grow" out of his homosexuality without his family watching over him. At the end of a year's time, he'll come back home ready for "normal" life.

Hannaham tells the story through Gray's voice, showing how a man can get to the point where he wants to flee his own life. This troubled but tenderhearted protagonist speaks in a plainspoken, gentle way. Hannaham describes Gray's inner turmoil in frank and direct detail, but lets us know how good Gary is as well.

That goodnessor, at least, complexitycomes through in Hannaham's other characters, too. Although Gray spends the novel's last third in a gay reform camp outside Memphis, and even though it's clear that Hannaham views such efforts as fruitless and damaging, he doesn't take cheap shots. Instead of mocking southerners, Bible-thumpers and gay reformers, Hannaham humanizes them. We see their flaws writ large, sure, but "God Says No" loves all of its characters, not just Gary Gray.

The novel works both as a wicked satire of conservative Christianity and as a sensitive portrait of a struggling Christian. Hannaham's contemporary South is a complicated place, where lust makes people strange, and love comes in more varieties than man-woman couplings. Through Gray's example, Hannaham shows how God might say "no" to Christians' rejection of homosexuality. The novel's so good, though, that God might just say "yes" to it.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.