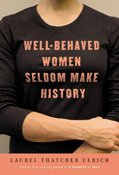

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich knows a thing or two about women. Whether misbehaved or well mannered, daring or demure, naughty or nice; every one of us deserves a podium from which we can broadcast our voices. In "Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History" (Knopf, 2008, $14.95), Ulrich gives all women—from Sweet Potato Queens to Second Wave activists—a place in the context of history. In doing so, she illuminates not only the testimonies of courageous heroines, but also the surprising notion that they needn't always be naughty to get noticed. Sometimes, well-behaved women do make history Ulrich seems to argue; just on their own calculated terms.

Ulrich fashions her argument (and iconic bumper-grazing "Well-Behaved" maxim) around three major works now considered standard reading in many women's studies programs: Christine de Pizan's "Book of the City of Ladies," Elizabeth Cady Stanton's "Eighty Years and More," and Virginia Woolf's "A Room of One's Own." She carefully dissects the texts with the precision of a historical surgeon. With her skilled hands, she offers readers a window through which to view the social injustices each female author faced in her own time, and why women seemed entirely absent from the versions of history they were taught.

Modern women might be shocked at how similar their challenges appear to our own. Ulrich quotes a Pizan scholar, writing, "It's not so much that Christine's consciousness is surprisingly modern, it's that the problems facing women in our time are surprisingly archaic."

Here, Ulrich celebrates the Amazon; a fierce female warrior who shunned society and sacrificed femininity to live free of male constraint. She sheds light on abolitionists and African slaves who fled the South not only to escape racism, but also the undermining of their own sex. She uncovers the roots of the American suffragist movement that produced the First Wave of feminism with its female leaders who dared suggest that even as white women, they, too, were slaves—to their husbands, society and the law.

Through her examination of Woolf's literature, readers get a glimpse of what it might have been like as a woman during Shakespeare's time by vicariously living through the Bard's fictitious sister Judith. And finally, Ulrich treats us to a brief timeline of feminist activity in the 20th century, which produced the bra-burning radicals of the Second Wave.

In most cases, life for our foremothers was just as we might suspect: a long stream of domestic duties and pious commitments like childbearing, rearing, mending and meal preparation. It was an existence devoid of formal education so that they might best serve their husbands and God.

But every now and then, Ulrich highlights a woman who reached beyond those petticoats of constraint to upend her world. Some, like Cady Stanton, broke through the sex barrier with a fierce determination no one could ignore. Others, like Rosa Parks, deliberately chose to behave in a manner that made a larger impact when people least suspected it. No matter, in both cases her ladies seem to say, "Misbehaved or not, we won't stand for subservience any longer."

Coming off the heels of an election year bursting at the seams with women, it's perplexing how at odds we remain with the notion that women can at once be powerful and feminine. We labeled Hillary Clinton everything from a "man-hater" to "a man"; simultaneously attacking her femininity, and so-called lack of it. Enter Palin—the Alaskan Amazon governor-cum-hockey-mom, clutching an infant in one hand and a hunting rifle in the other—who raised more eyebrows than any male counterpart. We assaulted her at a fundamental level for leaving her home and children to serve in political office, and then for superficial things like her wardrobe and hairstyle choices.

Both women had a hand in earning "Saturday Night Live" its highest ratings in 15 years. Apparently, whether poking fun at cankles or presidential pageant queens, we were listening. Perhaps the Third Wave tide is making its way in—only time can tell.

One thing is for certain: de Pizan, Cady Stanton and Woolf would delight in the fact that females were running for national political office, and that one of them triumphed to become our newest secretary of state. And then they'd pick up a pen and start talking back to themselves—writing books, giving speeches and organizing so that they might elect a sister once and for all.

Little girls and women of the world, Ulrich wants you to do that, too. Live and write your own versions of history, starting with Ulrich's very well-behaved record of fearless women past and present.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus