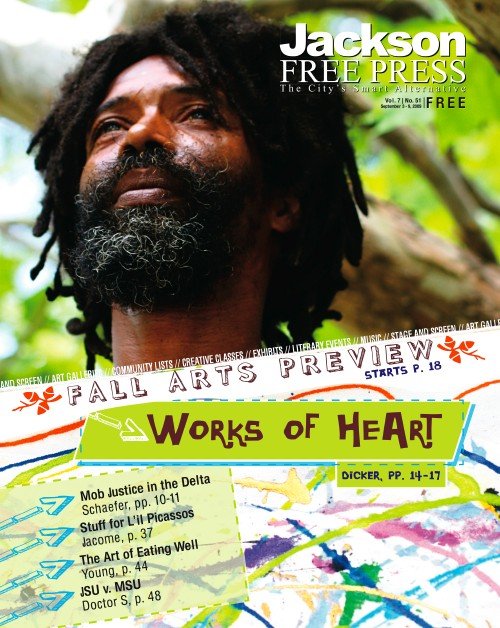

Michael Lewis stands in front of a table covered with a sheet of canvas, which he has splattered with colorful acrylic paints in the style of Jackson Pollock. He surveys his work in silence, straightens the canvas so it lies flat and picks up a small bottle of orange paint.

"I'm just gon' add a little," he says. He squeezes paint directly from the bottle and adds three large spirals along the bottom of the canvas and a few squiggly lines along the edges. His thick dreadlocks fall in his eyes, and he brushes them aside with his thin fingers.

"That's it," he says, bringing the bottle down on the table with an air of finality.

Lewis is a 52-year-old homeless man and a client of Stewpot Community Services, a non-profit organization that meets basic human needs like food, clothing and shelter. Lewis is also a talented artist, and he has found his niche in the HeARTworks program, which provides weekly art sessions for Stewpot clients. The program is independent of Stewpot but has ongoing permission to use its cafeteria space.

Through hour-long art sessions every Tuesday morning, Lewis has created a series of paintings that will be on sale at HeARTworks' first annual art show Thursday, Sept. 10, at Fischer Galleries in Fondren. Artists will receive 80 percent of the proceeds from their pieces, and Stewpot will receive 20 percent.

Founded a year ago by Stacy Underwood, and run through a partnership with her friend Jamie Randle, HeARTworks has created a way for Stewpot clients to find a voice through their art, share their talents and earn money from doing so. Volunteers have found themselves transformed by working with those less fortunate.

Now the program has a chance to expand its reach by sharing clients' work with the greater public through a one-night-only art show.

Art: The Great Equalizer

It is a Tuesday at 10 a.m., and about 20 people, mostly middle-aged and older, are seated at round tables in Stewpot's cafeteria, absorbed in creating art. A man with a short Afro and beard is painting an ocean scene, carefully dotting green paint onto jagged brown cliffs with a small brush. As he works, he talks to a friend seated next to him on a metal folding chair. At the next table, a couple of older women are gluing fabric squares to strips of white cardboard and adding touches of paint, while Stewpot staff and volunteers walk around the cafeteria setting up for the daily noon-time lunch.

Underwood and Randle had arrived at 8:45 a.m. as usual to transform the cafeteria into an art space for an hour. They're easy to spot, even in a big room. Both fit and beautifulUnderwood a curly blond and Randle a striking brunettethey are always in motion. You can hear them laughing and bantering with clients from across the room. They have covered the cafeteria tables with white butcher paper and distributed various art supplies according to the projects their students are working on. Each week, they carry client art projects and big boxes of suppliesoil pastels, clay, watercolorsup and down two flights of wooden stairs, from their cars and back.

The two women, along with potter and volunteer Warren Wells, circulate around the room and greet their clients with enthusiasm. They distribute snacks, like chocolate chip cookies, and give gentle pointers if the clients want them. "Add a bit of yellow here," the women suggest, "and maybe some polka dots?"

Underwood and Randle don't see themselves as teachers, but rather providers of a welcoming creative space. Though they might give artistic advice to clients, or present their work in an appealing way, they never alter the work itself. Over time, they've gotten to know their clients' preferences and regularly introduce them to new materials and project ideas. The most important thing, they believe, is that the clients enjoy themselves.

"You got the nose on that rabbit just right!" Underwood says, looking down at the drawing of a client named Mary Ann Young. "That angle is hard to do!"

Young, an older woman who always sits alone at a table by the window, continues looking off into the distance and doesn't reply.

Underwood raises her volume a notch. "Do you want to work on it a bit more?" she ask. Young doesn't react. Underwood nods and adds the painting to the small stack of artwork in her hand.

Randle leans over to Underwood, saying softly, "I asked Mary Ann if she wanted to work on it more, and she said, 'NO!'" She barks out the word gruffly and laughs. It's clear that Randle is fond of Young and is tickled by her personality.

"She's had enough for today, and that's OK," Underwood says, laughing, too.

I approach Darryl Washington, 41, to ask him about the art table he'll be featuring in the gallery show. He has painted a small wooden table silver and created a cityscape under its glass top out of a computer motherboard, a fan blade, and other recycled odds and ends.

Washington has titled this piece "City on the Sea." He points out an oil rig drifting on the water, and a helicopter hovering over the table, attached by a wire. Though it is difficult to understand Washington as he drawls and softly mumbles his words, he clearly demonstrates pride in his work.

Though he had liked to sketch as a child, Washington did not pursue art seriously until he moved to Jackson a year and a half ago. His small hometown of Tutwiler, in the Mississippi Delta, didn't have art classes or many other enrichment opportunities.

Washington left school in 11th grade to begin working as a residential painter, and then as a brick mason.

Upon arriving in Jackson, Washington helped paint two murals on Stewpot's Opportunity Center. Soon afterward, he discovered the HeARTworks program and began coming on Tuesday mornings.

One day, Underwood brought some tin-can tops and scrap wood to HeARTworks, and Washington decided to glue the pieces together to form a robot. He painted his sculpture, attached wires for hair and entitled it "Man on a Mission." This first foray into 3-D art eventually led him to design the art table.

Currently, Washington works as a landscaper a couple of days per week and hopes that his painting and 3-D art becomes successful enough for him to do it full time.

"There's no one that I love more than the other," he says. "If it's anything dealing with my hands, especially something like art, I just love it."

Around 10:50 a.m., tempting smells begin to fill the cafeteria as the Stewpot staff prepares lunch. At 11 a.m., Bingo starts in the library, where one of Stewpot's regulars loudly announces the letter and number combinations. People begin to drift in the door and take their seats at the lunch tables. Several students continue working under the ceiling fans and fluorescent lights, completely absorbed in their art despite all the distractions.

As I walk around the room, I'm struck by an awkward feeling. I can't tell who is "in need" and who is not. I hesitate to start asking anyone questions, because I don't want to make any assumptions about a person's socioeconomic status, mental capacity or role at Stewpot.

It occurs to me that this is one beautiful thing about art: It has the power to equalize. At HeARTworks, everyoneno matter what his or her circumstancesis an artist above all else.

'Mollison was Jesus to Me'

The half-hour service happens every day at 11:30 a.m., but today's service is special. It's a memorial for Mollison Holmes, one of Stewpot's longtime clients who died unexpectedly the previous weekend from a heart attack. The chapel is packed in a small room adjacent to the cafeteria, with standing room only.

Against a backdrop of muffled voices outside the door and the clamor of the lunch setup, the service opens with a prayer. The audience joins in to pay tribute to Holmes, a middle-aged man who was both deaf and mute. Several stand up and share stories about the ways Holmes expressed himself: through his warm smile, and through the paintings that were a source of confidence.

Underwood and Randle walk to the front of the room. They are both in tears. So is Greer, Underwood's 9-year-old daughter, who has come to HeARTworks today with her 7-year-old brother, Jimmy. Four-year-old Ian is home with a sitter.

"I loved him so much," says Underwood about Holmes, sniffling and wiping her eyes. "He was my first friend here at Stewpot."

She points to a framed picture on the wall, of a dark-skinned Jesus kneeling in the Garden of Gethsemane.

"The very first day I was in here, he did this, and it just took my breath away," Underwood says. "That was Jesus to Mollison, and Mollison was Jesus to me."

After Randle and several other folks share their memories of Holmes, the crowd sings a few rousing gospel songs, clapping and swaying. They give a proper send-off to a man who might not otherwise have had a memorial service at allif not for the collaboration of Stewpot and HeARTworks.

Through the program, Holmes was able to leave the legacy of his paintings. Some will hang at Stewpot and the Billy Brumfield house, the Stewpot temporary shelter where Holmes slept. A few pieces will go to his mother, and several of his best will be available for sale at the Fischer show. Underwood and Randle have intentionally priced them higher than the rest, to share proceeds three ways: among Holmes' mother, Stewpot and a fund started in Holmes' honor, called the HeARTworks Memorial Fund. The fund will launch a small library of art books, which Mollison loved, for anyone to use for inspiration.

"We feel that he would have wanted that," Underwood says.

'Same Kind of Different As Me'

After the service, Randle and I follow Underwood back to her house in Belhaven and sit down in the kitchen. The women's eyes are still red from crying, but they exchange stories and laughs about the morning's art session.

"You got more out of Darryl today then I ever have," Underwood tells me. She and Randle don't tend to ask about their clients' lives, because they want to build trust by not prying. Over time, she and Randle have learned bits of information about their clients, but they rarely have a complete picture of anyone. Despite the gaps in their knowledge, they have become close with the folks they've seen week after week over the course of the last year.

Last summer, Underwood got the idea to start HeARTworks after reading the book "Same Kind of Different As Me," by Ron Hall and Denver Moore. It tells the true story of a multi-millionaire and a homeless man finding common ground and lifelong friendship despite their different lots in life.

"(The book) puts an absolute new face on homelessness," Underwood says. "Everybody needs to read it."

The book so inspired Underwood that she decided that she wanted to volunteer with the homeless and needy at Stewpot. She began brainstorming ways to best use her talents.

For some time, Underwood had been searching for satisfying ways to make use of her art studies from the University of Mississippi. She had never felt called to run an art gallery or be a full-time artist herself. In fact, when she tried to paint on her own, she'd find herself staring at a blank canvas, frustrated by artist's block.

"Two weeks after I read ("Same Kind of Different As Me,"), it was like a cartoon lightning bolt," Underwood says with a laugh. "Art for the homeless. I just knew it. I feel like out of nowhere, God laid that upon my heart."

Rather than focus on children or women, she wanted to reach the "older, middle-aged, distraught community" who are often forgotten.

Nearly right away, the program began falling into place. Underwood e-mailed a similar art program for the homeless in Austin, Texas, for advice and received not only a gracious reply, but also an entire plan for program success. Within just a few weeks, she arranged to meet with Stewpot staff members Don London and Tara Lindsey and got permission to start HeARTworks sessions in the cafeteria the following Tuesday.

"She was just so excited and overjoyed," says Lindsey, who says that she found Underwood's enthusiasm contagious.

As a petite, privileged white woman walking into Stewpot to offer her first art session to a group of clients who were poor and mostly black, Underwood felt nervous. However, meeting the kind and hard-working people like Mollison Holmes convinced her that her idea might not be so crazy after all.

After the first session, Underwood knew that she needed help with the program. She introduced HeARTworks' to her long-running women's Bible study group and asked if anyone could volunteer on a regular basis.

Out of 20 or so women, Randle was the only one who raised her hand. The two women had at least a couple of things in common: They had both graduated from Jackson Academy, two years apart, and they had both studied art but hadn't yet found their creative niche. Randle, who lives with her husband and children in Madison, was a graphic designer turned professional photographer who had felt the need for inspiration in her work. HeARTworks was exactly the kind of opportunity she had been looking for.

Underwood and Randle began working as a team, providing art sessions for Stewpot clients every Tuesday. London vetted the attendees to make sure they were "on the up and up," as Underwood puts it, arranging for them to sign up for art passes at Stewpot's Opportunity Center.

Stewpot's clients took a while to adjust to the new activity. At first, they complained about their usual Bingo time being moved to accommodate the art. Some would ask for money every week, which frustrated Underwood at first. She turned to her faith for guidance.

"God just said, 'What do you expect?'" Underwood says. "'This is the most needy part of your entire city. You drive up with your highlights and your gold hoops, and you don't think you're going to be asked for a couple of dollars? Get used to it!'"

Once the women kept coming back to Stewpot week after week, Underwood and Randle say, the clients began trusting them as friends. They don't ask the women for money anymore. "I think they would feel guilty doing that," Randle says.

When clients do make requests, they are for small necessities. B.C., a man who always sits with his friend James and sips a cup of steaming coffee, asked Underwood for a pair of gloves and a hat last spring. This summer, he asked for a pair of sunglasses. Underwood is happy to oblige, because "so little means so much."

It is clear, when hearing Underwood and Randle speak, that the program is one of their greatest passions. They're happy that their older children have visited the program, so they can appreciate their station in life and understand the personal rewards of service.

HeARTworks "permeates every bit of our family life," Underwood says.

Everyone Is Changed

HeARTworks' Sept. 10 show at Fischer Galleries falls on the week of the program's first anniversary. Underwood says that it was difficult for her to ask others for help with the event. She thought that local businesses in particular are bombarded for donations all the time and felt nervous about being turned down.

Nevertheless, she mustered up the courage to e-mail out a few requests and was stunned by the outpouring of generosity.

Chris Newcomb, CEO of Newk's Express Cafe, said by e-mail, "Anything you need, gratis to you."

Tasho Katsaboulas, the owner of Kats Wine Cellar, said that he was thrilled to give back to a population that often passes through his property everyday. He volunteered to donate to the event every year.

"Everyone who gets involved is changed," Underwood says. "It's not that people don't want to help. They just don't know how."

Fischer Galleries owner Marcy Nessel was enthusiastic, too, when Underwood approached her about hosting the HeARTworks show. Nessel had volunteered with Stewpot during the early 1990s, providing peanut butter sandwiches and fresh fruit to children at the after-school program. She told Underwood that she would happily host the show free of charge. In fact, she said, "Thank you for letting me do this," and offered to have them back every year.

Nessel will help Underwood and Randle price and display the art in the gallery. Prices will generally range from $20 to $225, so the art is affordable for many, with a few items priced higher or lower.

Community members are invited to come by the gallery Sept. 10 between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m., for a sneak preview before the art is available for purchase (from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m.) Because there is another art show at The Cedars that night, Nessel hopes that art lovers will find it convenient to stop by both locations.

To prepare for the event, Underwood and Randle have taken over Underwood's attic. The women have covered a pool table and the floor with stacks of paintings, wooden frames and boxes of supplies.

"My husband can't wait for the show," Underwood says with a laugh, gesturing at the clutter.

Together, the women choose the best pieces from each client, making sure to select work from all of the 30-or-so people who have participated during the year. If Underwood wants to include a piece that Randle thinks won't sell, she vetoes it. When they disagree, they do it by laughing and sassing each other.

With the help of their friends from Bible study, Underwood and Randle have framed around 100 works and attached silver spoons to the lower part of the frames.

Most of the spoons are tarnished antiques, reminders of the beauty inherent in everyone, including those who weren't born with the proverbial silver spoon in their mouths.

Next to each piece of artwork will hang a card featuring the artist's picture and a few details about him or her, so buyers can feel a personal connection with those they've supported.

"The message a person sends when they put (HeARTworks art) on their wall is, 'I'm serving the community this way,'" Underwood says.

While Underwood and Randle have invited the artists from HeARTworks to attend the show, they expect that they would feel more comfortable having a private reception at Stewpot. For this reason, the women are hosting a celebratory brunch on the program's actual anniversary, Tuesday, Sept. 8. They will fill the cafeteria with the clients' framed artwork before taking it to Fischer. Bellwether Church will cater a hearty meal for clients, complete with table linens, to congratulate them on their work.

Until now, Underwood and Randle have bought most of the supplies for HeARTworks out of pocket. They hope that as the program grows, members of the community will also be inspired to give.

For starters, they hope to have a successful turnout at the Fischer Galleries show, in order to highlight the best aspects of Jackson's impoverished population and provide a way for them to earn money.

Change Your Own Life

Over the year, Underwood and Randle have seen positive changes in their clients. Margaret Lear has improved immensely in her art skills, for example. Other clients, like Mollison Holmes, learned to express through art what they can't articulate. The women have seen clients build confidence in themselves and trust in other people. Even when the HeARTworks participants are homeless, they have something to look forward to each week: the pure enjoyment of creating art in a safe space.

Underwood and Randle have seen not only changes in their clients, but changes in themselves. Underwood says that she now understands the peace that can come with living simply. She's also learned what it means to look someone in the eye and really see that person, no matter who they are.

"Now I'll be driving down the road and see someone who looks like they've been walking a really long time and I'm wondering: 'Oh, do I know them? Is that Michael? Is that James? Does he need a ride?" Underwood says, laughing as she mimes craning her neck out of a car window.

"I want to pull over and get 'em," Randle says, "Which I would never have thought of before doing this program. I would have been scared to death. There used to be a fear around homeless people, and I don't have that anymore."

Both women say that they've realized how much of a difference just one person can make in a community, and how much a volunteer benefits from service.

"The life you change is your own," Underwood says. "Serving and giving, you're really doing that for yourself."

While Underwood is content with helping even one disenfranchised person express himself through art, she is eager to expand the program. One significant development is that Frank Spencer, the CEO of Stewpot and a lawyer, is helping incorporate HeARTworks as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Eventually, contingent on sufficient funding, Underwood would love to start an urban art center with a storefront to sell clients' art.

It all started with a stroke of inspiration, and one year later HeARTworks has brought together Jackson area residents from all walks of life: volunteers, the homeless and needy, nonprofit staff, small business owners and potential art buyers.

'There's Some Good to it, I Guess'

Michael Lewis is reading an article about the program that has just been published in Metro Christian Living, a free monthly magazine. Lewis traces the lines of text slowly with an extended index finger. He had worn the same look of intense concentration the previous Tuesday, while he was painting.

"What do you enjoy about painting, Michael?" I ask him. Still reading, he takes his time answering me.

"It just changes your day," he says, without taking his eyes from the magazine or his finger from the page.

Lewis, in a plain white T-shirt with a large wooden cross hanging around his neck, lays down the magazine and walks over to his newest painting, which is drying on a table nearby. On a small piece of canvas, he has squirted swaths of glossy black and white paint on top of a wild smattering of color.

"I call it 'Out of Line,'" he says, the wooden cross shifting across his chest as he gestures to his work. Lewis pauses, as if considering why he chose the title.

"Everything's not straight," he says, as serious as ever. "It's not perfect, but there's some good to it, I guess."

HeARTworks Show at Fischer Galleries

HeARTworks will display its clients' work Thursday, Sept. 10, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. at Fischer Galleries (3100 North State St., Suite 101, 601-291-9115). Art is available for purchase during the reception only, from 5 to 8 p.m. Cash, check and credit cards are accepted. Eighty percent of proceeds benefit HeARTworks clients directly, with 20 percent supporting Stewpot.

Newk's Express Cafe and Kats Wine Cellar will provide food, including soup samples, and beverages.

Around 100 pieces will be available for purchase, including paintings, sculpture and found art. Framed art will sell for between $20 and $225. Smaller items such as miniature spoon keychains, T-shirt and note cards will be priced from $5-$10.

Ways to Get Involved in HeARTworks

1. Support the program financially. Buy art pieces at the Fischer show Sept. 10. Donate to the program, in any amount. Your funds will go directly to supplies and snacks for clients in the Stewpot community.

2. Donate art or food supplies. Any new or gently used art supplies of all kinds, including salvaged materials, are welcome. You may also donate individually wrapped, non-perishable snacks.

3. Volunteer. On Tuesday mornings, volunteer with the clients, distributing art supplies and snacks, providing feedback, and doing art alongside them if you like.

To donate or volunteer, contact Stacy Underwood at {encode="stacyu@comcast.net" title="stacyu@comcast.net"}.

Be sure to check-out the JFP Calendar for listings of art shows, music performances, and live events.

Nathan Glenn is on Fire

The World's Window

Mississippi Blues: A Pictorial History of Poverty in the Rural South

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.