The story of Mound Bayou, Miss., is as improbable as it is inspiring. In 1887, former slaves founded the town in the Mississippi Delta wilderness as a haven for former slaves. Mound Bayou thrived culturally and economically for five decades, reaching a population of approximately 8,000 as it overcame the Jim Crow laws and poverty that plagued many southern blacks after the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877).

One of the more improbable facts is this: The founders' ideal of a separate, self-reliant, educated and ethical African-American community had developed on a plantation owned by Jefferson Davis' older brother, Joseph.

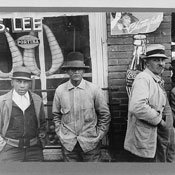

The rise and decline of Mound Bayou is told in an eye-opening, though somewhat disjointed new photo exhibit developed by the Smith Robertson Museum. "Mound Bayou: The Promise Land, 1887-2010" begins with multiple panels of essential written history. The exhibit offers descriptions of the more than 50 enlarged black-and-white, colorized and color photos that follow with only brief captions that lack context. What do the studio portraits of well-dressed citizens tell us, for example, if we don't know the subjects' identities or if they were typical of the population?

A street map placing the photos geographically would have added to our understanding. Recreation and the arts—important aspects of community life—go unmentioned.

On the other hand, the exhibit structure allows viewers to draw their own conclusions. Here are some of mine:

Mound Bayou had many distinguished citizens. Dignified portraits of banker Charles Bank and religious leader Rev. A.A. Casey hang near a snapshot of a smiling Dr. Moise George seated in his Model T.

No one was more important than city founder Isaiah T. Montgomery, a refined man in the photos. Born on Hurricane Plantation near Vicksburg, he was raised with owner Joseph Davis' utopian ideal of an educated slave population with limited self-government. Montgomery's father, Benjamin T. Montgomery, was an educated, high-achieving slave and a friend of Davis.

The father, with Davis' permission, owned a store. Its profits enabled Montgomery to hire a tutor for the Montgomery and Davis children, who learned together in a classroom.

After the Civil War, the elder Montgomery bought the plantation land and established the cooperative black community of Davis Bend. The venture prospered until hit by low crop prices, floods, insects and a labor shortage. Community leader Isaiah Montgomery's search for a more lucrative site led him to found Mound Bayou.

Mound Bayou's leaders were politically savvy. Montgomery worked closely with educator and national black leader Booker T. Washington to develop Mound Bayou's laws and government. A circa 1900 photo shows Washington on an outdoor platform leaning into the crowd as he makes a point. In a 1912 photo, Washington is speaking at the dedication of the Mound Bayou Oil Mill and Manufacturing Co., reportedly attended by 16,000.

The citizens exude a sense of dignity. In posed and candid photos, people were neatly dressed and generally appeared proud. "They looked different than most people who were just coming out of slavery—the intelligence, the ingenuity, the pride, the dignity," said Museum Manager Pamela Junior.

The community revered education. Photos show large, attractive brick schools. "Education was a given in Mound Bayou," Junior explained. "It wasn't a given in other places. When you went out into the Delta, there was not always an education system."

Residents appreciated beautiful architecture. Montgomery lived in a large brick house with an enclosed wraparound porch, the yard filled with flowers. Banks owned a one-and-a-half-story wooden house with a wraparound porch covered in part by a gazebo, all of which cost almost $10,000 to build in 1908. Even a farmhouse featured a gabled entrance and a thick crop of sunflowers out front.

Fine housing implies a strong economy. Mound Bayou had banks, stores, a railroad station and a newspaper—all black-owned—plus several public and private schools. The community made most of its money from cotton, timber and corn. For a time, Mound Bayou was the third-largest cotton-producing town in the South.

Folks were ethical, but sometimes tempted. A 1939 downtown sign that was either a joke or an invitation said: "The Royal Club: Wines, Beer & ____?"

In 1914, declining cotton prices began years of economic problems exacerbated by the Great Depression in the 1930s. Then, in 1941, a fire destroyed several downtown businesses.

In recent years, Mound Bayou has suffered economically like most Delta towns. The population hovers at about 2,000. But in its heyday, Mound Bayou was a model community, as this exhibit shows.

"Mound Bayou: The Promise Land, 1887-2010" will be displayed at the Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center, 528 Bloom St., through June 30. For more information, call 601-960-1457.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.