Lincoln "Chips" Moman is one of the most successful record producers in history. A music visionary with a knack for matching songs with artists, he was the genius behind Elvis Presley's "Suspicious Minds" and "Kentucky Rain," Dusty Springfield's "Son of a Preacher Man," Neil Diamond's "Sweet Caroline," Dionne Warwick's "Lost that Lovin' Feeling," Petula Clark's "People Get Ready," Wilson Pickett's "Midnight Mover," Joe Tex's "Hold On To What You Got," Willie Nelson's "Always on My Mind," and the list goes on and on.

Carrying out Moman's vision was an extraordinary group of southern-grown musicians known as the 827 Thomas Street Band. In 1985, Moman told me: "I'm a pretty good musician, but every one of them is better than me. I'm not in their league."

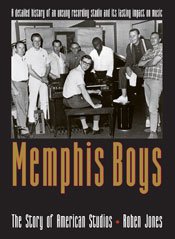

The story of the 827 Thomas Street Band is told in Roben Jones' "Memphis Boys: The Story of American Studios" (University Press of Mississippi, 2010, $50). Handpicked by Moman for his Memphis-based American Studios, the band played together through the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Moman's career had three major creative surges during that time: the early years at American Studios; the mid-years at his Nashville studio; and his 1985 return to Memphis, where he recorded at a renovated fire station named 3 Alarm Studio. This book covers the first two periods, but not the third, even though his band stuck with him to the bitter end, commuting to Memphis from Nashville.

Today, the musicians all live in Nashville (Moman resides in Georgia) where they still are considered among the best studio musicians around. They acquired the name "Memphis Boys" when they moved to Nashville in 1973 and started churning out country hits that had a decidedly Memphis feel to them, which is to say the music was soulful and had more of a rock edge to it than the music recorded by Nashville session players, few of whom employed accent horns, hard-driving drums or blazing guitar riffs. Doing what came naturally, the Memphis Boys laid the foundation for country music's Outlaw Movement and pretty much everything that is now defined as "country."

I have known Moman and the "Memphis Boys" since the mid-1980s, when I wrote about music for The Commercial Appeal and later in my magazine, Nine-O-One Network, the first southern-based publication to ever achieve newsstand distribution in all 50 states. I featured Moman and the band in the first and several subsequent issues, and spent countless hours in the studio with them, watching them effortlessly weave Moman's inspired ideas and gambler's hunches into memorable music.

Each of the players in the 827 Thomas Street Band is a star in his own right and could have achieved success on his own, but they have recorded together for more than four decades because they are a family, having started out together in their late teens and early 20s, going through all of life's crises and challenges as a supportive unit. Today they are in their late 60s and early 70s, miraculous survivors of a hard-living culture that long ago felled most of

their contemporaries.

Two of the core band members are Mississippians—keyboard players Bobby Wood and Bobby Emmons. Two are from Memphis—Gene Chrisman on drums and Mike Leech on bass. The fifth member, legendary guitarist Reggie Young, is from Osceola, Ark. Once they began cutting hit records in the early 1960s, as often as not with African American singers, record executives from New York traveled to Memphis to witness the studio's "black" music phenomenon first-hand. To their amazement, they discovered that all the band members were white.

Years later, after they had relocated in Nashville, playing sessions with Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, and Kris Kristofferson, Moman found himself in trouble with the IRS over a bill for past-due taxes. In 1986, Moman recalled to me the band's reaction, explaining his devotion to his musicians: "Bobby Emmons was the first one. ‘I just heard about it,' he said. ‘The bank told me they would let me have $80,000, and I'll have it for you by this afternoon.' Reggie came in and said, ‘Hey, man, I'm gonna borrow some money on my farm. I can let you have $100,000.' Bobby Wood called. They all came to bail my ass out. I said, ‘I don't want you to do that. Let me see if I can't take care of it myself,' and I did take care of it myself. But do you know what kind of an honor it is to have your friends offer to do that for you? These are special people. Whatever I got, it's theirs if they want it. That's the kind of relationship we've got."

There are things that I like about this book—beginning with the fact that someone took the time to tell their story in great detail (few people in Memphis knew their names, even when they were enjoying a string of more than 100 hit records)—but there are things I do not like such as the hefty price; the two-column text format, which makes the book read like a dictionary; the author's excessive reliance on interview quotes at the expense of research (just because someone says something doesn't make it true); and the passionless, plodding writing style that does not come close to capturing the energy that characterizes the incredible music created by the Memphis Boys.

That said, the book is well worth reading. To put it in musical terms, it may not be a chart-topping hit, nor will it win the writing equivalent of a Grammy, but you can learn things that you did not know about the most respected studio band in America.

James L. Dickerson is the author of two award-winning books that focus on Memphis music, "Goin' Back to Memphis: A Century of Blues, Rock ‘n' Roll, and Glorious Soul" (1996 Gleason Award finalist) and "Mojo Triangle: Birthplace of Country, Blues, Jazz and Rock ‘n' Roll" (IPPY best nonfiction book of 2006 from the South).

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus