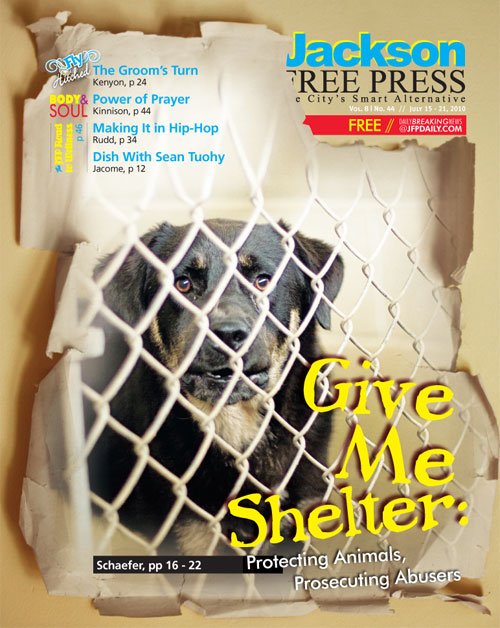

The mutt turned up in the Providence Madison subdivision one day in early October 2009 . A black and tan hound mix, around 7 months old, she was skittish around the neighborhood's residents. She cowered if a human tried to pet her, tucking her tail between her legs, even urinating. Some residents began feeding her, though, leaving dog food on the road for her to eat. When she got into a set of garbage and recycling cans, though, a neighbor called Madison County Animal Control.

Canton animal-control officer Alonzo Esco picked up the stray a couple weeks later with help from a prison trusty, and transported it to the Ruger Animal Wellness Center's kennel on U.S. Highway 51, where the county keeps strays and other animals for owners to claim them. After seven to 10 days, the county usually transports the animals to the Mississippi Animal Rescue League in south Jackson, which has agreements with many regional animal-control units to house--and euthanize, if necessary--animals they pick up.

At the Ruger kennel, the stray settled down. Melissa, who asked that her last name not be used to protect her identity, is a Madison County resident who fed the dog in Providence Madison. She visited the dog at the kennel and began calling like-minded animal advocates in the area, looking for a foster home or family to adopt the mutt. Just before Thanksgiving, Melissa reached Debbie Young, who said she could house the dog at her home in rural Madison County.

"(At the kennel), she would eat out of my hand, she would come up to me, she would roll over, she started to let me pet her," Melissa said. "You could tell she was starting to trust people a bit more. ... She was just an unsocialized dog that would've been a great pet."

She never got the chance. Madison County sheriff's deputies found the dog's body, along with those of six other dogs in a ditch. Madison County police arrested Esco on charges of animal cruelty, a misdemeanor, and illegal dumping. Prosecutors allege that he shot as many as 100 dogs and dumped them in a number of creeks and drainage ditches around Canton.

Antiquated Laws

After 32 years, Debra Boswell is wearily familiar with human cruelty to animals and the difficulty in prosecuting it. Since 1978, she has served as the director of the Mississippi Animal Rescue League. A short woman with cropped brown hair, she speaks rapidly, as if trying to get through the disheartening descriptions of her work as quickly as possible. Boswell can rattle off citations from the Mississippi Code and Black's Law Dictionary with a facility that is startling from a former administrative assistant.

The state's misdemeanor animal-cruelty law is so vague that it hampers prosecutors, Boswell said to the Jackson Free Press when I visited her office in late June.

"We are antiquated in our laws. Alabama, Louisiana, Georgian, Tennessee--they're all flying, passing us by," Boswell said. "We've not even been successful trying to get basic shelter for animals--it's not even required. So we have to use the section of the our code, 97-41-9, that says you will not neglect or refuse to furnish an animal necessary 'sustenance, food or drink.' We have to take that word 'sustenance' and get creative with it, get creative with the word 'neglect.'"

The MARL facility looks a bit like an elementary school, with high windows, industrial tile and water-repellant walls to make sanitation easier. A small black-and-white Boston terrier sat on Boswell's desk chair.

"Get up. You're not being interviewed," Boswell said cheerfully, and the dog obeyed, trotting out the door.

MARL has grown tremendously since Boswell first took over, during a leadership overhaul following a fire. The shelter now takes in more than 15,000 animals a year, compared to roughly 3,000 per year when Boswell joined. The League(tm)s budget has swelled accordingly, from $35,000 to $850,000 annually. Most of the facility's funds come from private donations, along with some foundation grants, Boswell said.

The shelter sits on 47 acres off of Greenway Drive, near some warehouses and a Hindu temple. The large property is important, because MARL now takes in around 40 horses a year, Boswell said. Horses used to be rare, but the economy has made caring for them harder, and many owners are simply giving them up.

On a chair outside Boswell's office door, there is a thick black binder with the label "Euthanizations 2010." It's a reminder that the shelter's "no-animal-turned-away" policy also means that MARL must eventually euthanize between 70 and 72 percent of the animals it houses. The shelter facilitates adoptions, but some of the animals are simply not adoptable, Boswell said. They may be old, sick, ill mannered or just unlucky.

Perhaps as a result, the shelter does not feel overcrowded. The dog runs are noisy, but spacious. Boswell shows me the facility's "Rainbow Room," where families can request private euthanasia for their pet. There's a table lamp, providing softer light than overhead fluorescents and a book called "Dog Heaven."

In addition to housing animals, MARL works with law enforcement across the state in cruelty and neglect cases. Boswell has stacks of pictures documenting the horrors MARL workers encounter.

She lays out a series of pictures taken from a pet-hoarding case near DeKalb, in Kemper County. MARL workers recovered 184 animals, many of them already dead, from the house. The floors were covered in several inches of feces, trash and other filth, and workers needed to use masks just to breathe.

For hoarding cases, a civil action is often effective, Boswell said. Under the civil action, MARL can seize the pets until the hoarder can prove that he or she can care for the animals.

"You've got the little old lady, the cat lady who lives with 75 cats that she can't take care of, and she's in ill health," Boswell said. "Well, all you want to do is get some relief for the cats. You don't want to send the 75-year-old lady to jail."

Boswell brings out more pictures: long-haired dogs whose owners did not brush them, rescued with fur so matted they could hardly walk; starved dogs with backs arched from malnutrition; a tiger seized by Pearl Animal Control that weighed half what it should have.

"With pet overpopulation at the level it's at, 3 to 4 million animals are killed every year in shelters across the country," Boswell said. "No animal should have to die in a shelter. Our goal, for all of us, is that there's (an adoption) waiting list for animals that are coming into shelters."

‘Humane Methods'

On Nov. 24, 2009, Debbie Young called Ruger kennel to ask about fostering the stray that Melissa had looked after. She was too late, the kennel staff told Young. Alonzo Esco had come by that morning and picked up seven dogs: the hound mix, a Rottweiler, two pit bulls, two Australian shepherd puppies and a beagle. He was supposed to transfer the dogs to the Mississippi Animal Rescue League. During the summer, MARL can easily take in more than 100 animals a day, and it would have likely euthanized at least some of the Madison County dogs. Young called MARL, hoping to alert staff that one of the dogs Esco was bringing had a foster home.

"That's when it began to get a little deep, because they weren't there," Young said. "The Animal Rescue League said he had not brought animals there, and they had not seen him for several months."

Young and Melissa then called the Canton Police Department in the hopes that dispatchers could tell Esco that the hound mix had a home. Dispatch gave them another puzzling response: Esco was on vacation.

Through the kennel director, who finally reached Esco, Young learned that Esco claimed he had euthanized the dogs. She filed a complaint with the Canton Police Department.

"If he euthanized them, that's a controlled substance," Young said. "You can't use the euthanasia drugs unless you're certified to do that. If he shot them, then that constituted cruelty, and we needed to find out."

Young finds Esco's alleged actions especially infuriating because of his responsibility.

"The thing that gets me (is that) an animal-control officer is the one person that is paid to actually be the advocate for animals," Young said.

"I understand that those animals would've been put to sleep, because in Canton we've got more (animals) without homes than we've got good homes for them to go into or people that are willing to adopt. But not the way it was done, shooting them, when they're terrified. I don't know if they were running or if he point-blank shot them. There are humane methods for euthanasia. ... Does he know they were dead? Was he absolutely sure before he threw them off into the creek?"

Linked Violence

The city of Canton fired Esco Jan. 5, 2010. After a June 21 probable-cause hearing, Canton police arrested him on charges of misdemeanor animal cruelty and illegal dumping. On Aug. 11, he will go on trial in Canton Municipal Court. He faces a maximum $1,000 fine and six-month prison sentence for each of the five animal-cruelty counts.

But the June arrest was not Esco's first. In April, only months after he was fired, Canton police arrested him on domestic-violence charges for allegedly choking and hitting his live-in girlfriend.

For Nancy Goldman, Esco's alleged domestic violence is further proof that Mississippi needs a felony animal-cruelty law. Goldman is vice president of Mississippi-Fighting Animal Cruelty Together (MS-FACT), a relatively young organization that campaigns for stronger animal-cruelty legislation. Mississippi is one of only four states--the others being Idaho, North Dakota and South Dakota--without a felony animal cruelty law.

"People that are cruel to animals often have the potential to be violent offenders against humans," Goldman said.

Goldman, a psychiatric nurse specialist with her own practice in Jackson, can recite a litany of cases. Luke Woodham, for example, who killed his mother and two students at Pearl High School in 1997, tortured and burned his family's dog five months before his school rampage.

In March 2009, 20-year-old Travis Bradford of Natchez doused his dog in lighter fluid and set her on fire but received only six months in jail, the maximum penalty for misdemeanor animal cruelty. Bradford was in training to become a home nursing assistant for elderly patients, and without a felony conviction, his future employers will have a harder time knowing about his past cruel acts, Goldman said.

Goldman's concern is a personal one. She lost a Labrador mix, Monty, the day after Christmas 2003, when a neighbor shot the dog as it crossed the property line of her home in Learned. The shooter had permission from Goldman's neighbor to hunt on the land. Goldman heard the shot as she read the newspaper by her outdoor fireplace. She sprinted 150 yards to catch up with the shooter as he was leaving on an all-terrain vehicle. At the time, Goldman was unaware of the state's misdemeanor law and did not press the matter with the county Sheriff's Department.

"That was one of the best dogs we've ever had," Goldman said.

In 2008, MARL and other groups pushed for a felony law--restricted to dogs and cats--with the help of a lobbyist provided by the U.S. Humane Society. The effort proved fruitless, but a coalition of citizens emerged around the issue and formed MS-FACT.

"These weren't people associated with animal agencies," Boswell said. "These were private citizens or the voters that put (legislators) in office, and we thought that they had a greater chance for success than we, as an agency, did."

A Close Call

MS-FACT began its push for a felony law this winter, with a petition campaign that gathered more than 25,000 names in support of a stronger law. As with earlier campaigns, the state Senate approved a bill that met advocates' requirements.

The bill, S.B. 2623, sponsored by Sen. Billy Hewes, R-Gulfport, proposed two principal things. First, it expanded the crime of misdemeanor animal cruelty to apply to "any living vertebrate creature except human beings and fish." More significantly, though, it created a felony crime of "aggravated cruelty" to a dog or cat, carrying a jail sentence of between one and five years and a fine of $1,500 to $10,000.

The bill also allowed for a court-ordered psychological evaluation and follow-up visits from a humane officer for up to a year. In an attempt to skirt any objections from the Farm Bureau or skeptical legislators, the bill carried exemptions for self-defense, defense from "economic injury," veterinary practices, ear-cropping and tail-docking, "accepted agricultural and animal husbandry practices," hunting and medical research, among others.

The Senate passed the bill Feb. 4 by a near-unanimous vote, with only Sen. J.P. Wilemon, D-Belmont, opposing it.

When the bill moved to the House of Representatives, however, Speaker Billy McCoy, D-Rienzi, "double-referred" it to both the Judiciary B and Agriculture Committees. Double-referral makes a bill's passage much more difficult, since the measure must clear two sets of committee members before making its way to the full House for a floor vote. And referral to the Agriculture Committee meant that the bill would have to contend with the Mississippi Farm Bureau, whose lobby is especially powerful in the committee. S.B. 2623 died in both committees, never coming up for even a committee vote.

Nancy Goldman, like many members of MS-FACT and other advocates, believes pressure from the Bureau led to the bill's failure.

"(Farm Bureau President) David Waide, I think, initially thought of what is called mission creep: ‘You give them an inch; they'll take a mile," Goldman said. "There was all this false dissemination of information that we were backed by PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), which is pretty ridiculous. I mean, I'm having a steak tonight. I have a leather belt."

The Farm Bureau's opposition is especially hypocritical, Goldman argues, because the state already has a felony crime for cruelty to livestock.

"It's mainly because livestock is considered a commodity," Goldman said. "If you've got a cow or goat or sheep that someone maliciously kills, then that is a felony. What we're trying to do is to get the same penalties that apply to livestock apply to domesticated dogs and cats."

McCoy told the Jackson Free Press that farmers were simply too wary of a felony law involving animals. McCoy said he could not talk specifically about how the failed Senate bill would have made farmers vulnerable.

"We all are--farmers, especially--very cautious when you're talking about a felony, because there are so many things that happen when you're working with animals and somebody could make a charge any day," McCoy said. "I don't know a member of the House of Representatives who's not totally, 100 percent appalled that anybody would want to abuse an animal in any way. But for people that don't understand the care and transportation of animals, it would be easy for them to make an accusation against a farmer or somebody that deals with animals professionally. Just the word 'felony' brings much caution to our minds."

Representatives of the Farm Bureau did not return calls for comment.

MS-FACT is increasing its lobbying and petition efforts this year, Nancy Goldman said. She estimated that the group has added between 3,000 and 5,000 new names to its petition since January.

Boswell said old attitudes about private property are partly to blame for the inadequacy of animal-cruelty legislation at the state level. Laws that mandate shelter or spaying and neutering don't mesh with the rural sensibilities of some lawmakers, she has gathered.

"'You can't be telling people what to do with their private property. You can't, you can't, you can't.' That's what we hear from the Legislature," she said.

Missing Misdemeanors

Not all animal advocates agree with MS-FACT's focus on passing a felony law. Doll Stanley, director of the Project Hope animal sanctuary in Grenada, came to Mississippi 17 years ago to investigate licensed animal dealers for In Defense of Animals, an animal-welfare group active across the country. She stayed, however, when Debra Boswell and others urged her to set up a sanctuary.

At the Grenada site, Stanley fosters and rehabilitates rescued animals. Every other month, she transports roughly 60 dogs to Colorado, where there are families eager to adopt, she said.

Stanley, who calls Boswell her "mentor," believes the state first needs to tackle its existing, inadequate misdemeanor laws.

"The misdemeanor laws we have right now in this state are about as good as toilet paper," she said. "They're thin; they don't have definitions; they won't hold up in a lot of court cases."

Stanley concedes that an ideal cruelty law would have elevated penalties for especially heinous acts of cruelty--like maiming and burning that usually result in an animal's death. But first, the state needs laws that will protect animals that are living but neglected: those suffering from mange, starvation or exposure. And passing a felony law is still no guarantee that prosecutors will apply it and win, she noted.

"Just because you've got a felony law doesn't mean you're going to get a grand jury to say there's enough evidence for a former felony trial that spends taxpayer's dollars and time and then overcrowds our prisons,"

Stanley said. "We've got to work with what we've got. And if we want more, then get out there and get more tax money so we can have more time in jail."

People Problems

A felony law would be a welcome tool for animal control, Gerald Jones said.

Currently the Jackson Police Department's deputy chief for standards and training, Jones has overseen the city of Jackson's animal-control unit since 1998. He has seven animal-control officers working in his section. They have been busy this summer, answering 500 complaints and handling 25 cruelty cases in June alone. Most of those cruelty cases are weather-related neglect, he said.

Jones said his unit aims to prevent the animal-cruelty cases that would qualify as felonies.

"I believe that individuals who abuse animals start out not caring for the animal physically," Jones said. "In other words, before he kicks him off the porch, this is the same animal that doesn't get proper food. What I want to do is start with those complaints. To me that's an indicator that this individual does not care about the animal."

The gaps in state law have left counties and municipalities with the responsibility of defining animal cruelty more precisely. Hinds County attempted to do that June 21, when the Board of Supervisors approved a stronger, more detailed misdemeanor ordinance that describes proper shelter for horses and dogs and specifically bans long-term tethering

of animals.

The county has only two animal-control officers, and an ordinance's effectiveness will depend in no small part on them.

Deputy David Fisher is a stocky guy with a perpetually furrowed brow. If most animal advocates are overflowing with stories and compassion, Fisher is on the other side of the spectrum--the taciturn, horse-whisperer type. The son of the county's former Emergency Operations Director, Larry Fisher, David Fisher has worked for the Sheriff's Department for almost 12 years but only moved to animal control four years ago.

"For years, I begged for this job, because I love animals" Fisher said. "Normally, I would say this isn't the kind of job people are going to beg for."

We met in a parking lot on Terry Road near Interstate 20, and I hopped in his county vehicle, a Ford Expedition with a plastic partition separating the trunk. There was a dip cup and a coffee thermos in the two cupholders, files and animal food on the backseats.

Fisher said that he needed to check on a stray that he'd been trying to trap for a while, but first he needed to pick up more bait. He tried cat food, to no avail. He was planning to use chicken fingers, but if that didn't work, it was on to meatloaf.

We stopped at a Shell gas station at Raymond and Springridge roads in Byram to buy bait. Fisher bought seven fried chicken strips. The cashier asked if he would like fries, too. As we walked out, a ragged-looking, longhaired black stray trotted up to one of the pumps. Fisher asked the station's owner, clad in a white T-shirt and baseball cap, if he wanted anything done about the animal.

"I ain't studying on it," the owner said. The dog's owner lives up the road, but he's just had heart surgery, and Fisher shouldn't bother him, he added.

"Can't do nothing about that," Fisher said as we climbed back in the truck. "He said he'll talk to the guy."

As he pulled out, the owner re-emerged from the station with a bowl and a bag of dog food.

When we reached the stray on Parks Road, there was a dog bowl with water in front of a crumbling, abandoned brick house. Fisher set the trap and tore the chicken tenders in pieces, dropping them in a trail from the grass into the back of the trap. The dog appeared, a young female with black and white markings, and a man approached from across the street.

"I couldn't get her to come to me," he said, nearing the dog as she circled the trap.

"Unless you can catch her, let her go into the trap," Fisher said. "I'm trying to fix this problem."

"I hate to see her go," the man said.

Fisher asked where the man lives. He points across the street. With his mother and father, he said. Those are the people who complained to Animal Control, Fisher

told him.

The dog wolfed down the chicken tenders outside the cage and then gingerly stepped inside. She ate every piece except those against the cage's far wall, the ones she would have to reach further for and step on the cage's trigger. We climbed back into the truck and pulled out.

"Did you get a good education on how people are?" Fisher asked me. "They call about wanting her gone and then turn around and want to interfere with me here. Last week I put a trap out here and somebody actually shut it on purpose."

When I talked to Fisher two days later, he said that when he checked on the trap the next day, someone had shut it again. The dog was still loose.

A Second Chance

After The Flood

CORRECTION: The print version of this article contained several errors. Nancy Goldman is vice president of MS-FACT, not secretary. Goldman did not blame House Speaker Billy McCoy and the Mississippi Farm Bureau for the failure of last year's felony animal cruelty bill; she suggested that pressure from the Farm Bureau may have led to the bill's failure. Travis Bradford was sentenced to six months in prison, the current maximum penalty for animal cruelty, not one year. Finally, Luke Woodham tortured and killed his family's dog, not a cat. The article above has been revised to reflect these corrections. The Jackson Free Press apologizes for the errors.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus