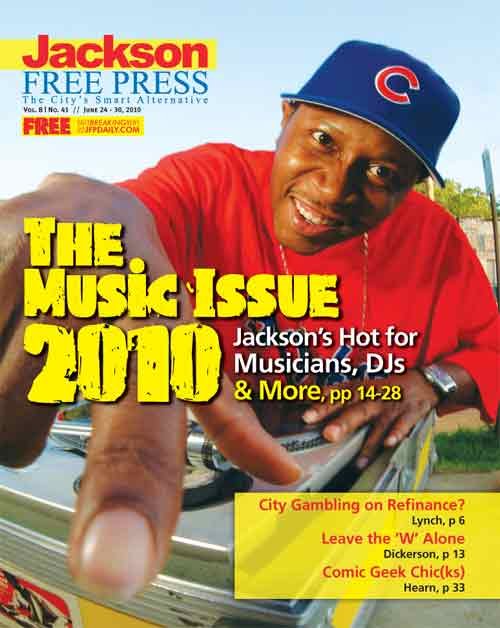

He walks around, shaking hands and hugging people like the most charismatic politician. Slightly baggy jeans, simple loafer-like shoes and a mint green short-sleeved shirt are not the typical attire of someone running for office, but a suit and tie in this environment would stand out like a bonafide Jezebel at a summer tent revival.

Keri Nash, the host of "Spoken Word in the City" at The Roberts Walthall Clarion Hotel downtown, points in the event coordinator's direction. "Give it up for my man, Scrap Dirty. That's my dude over there, y'all. He helps make all this sh*t happen right here."

Thirty-eight-year-old Scrap lifts his tattoo-emblazoned right arm to the crowd, smiles, then nods as someone walks up to him to ask a question. The two rush off. There is, undoubtedly another mini crisis happening that Scrap must handle.

‘A Little Jekyll and Hyde'

In 2000, Rob Nichols—who got his pseudonym Scrap Dirty because he was "scrappy, like the dog, in the street a lot and had a quick temper" and "dirty for Dirty South"—was the host of "Saturday Night Party Mix" at WJMI, where he'd worked for four years. He walked in one day and was told he was being let go.

"I don't even remember what I did, honestly. Like I don't even think I asked at the time. I was just like, ‘OK, I'm fired; what's next?'" Scrap says.

The answer changed the deejay's career path.

"I knew I wanted to create something for deejays who'd been let go like I had," he says, so he started managing, working with Atlanta-based Kurupt of the Tha Dogg Pound, in 2000. The deejay, who'd grown up spinning house music on Chicago's south side, was broadening his horizons.

"To be a manager, at your best, you have to have patience and be a little Jekyll and Hyde. There has to be that compassionate part and that part that don't take no mess," Scrap says.

Though he'd never managed anything besides his own career before, the deejay had experience—at least academically.

Scrap graduated with a bachelor's degree in marketing in 1997 from Jackson State University. Between graduating from Walter Lutheran High School in Chicago, and moving to Jackson to attend JSU in 1993, the deejay spent his time trying to figure out what he wanted to.

"All I knew for sure, at first, was that I was tired of going to Lutheran schools, and I wanted to get away. I went to Lutheran schools from first grade all the way through high school. It was either Concordia College or Jackson State, where my dad went," he says.

To escape his strict school regiment, the adolescent started breakdancing. "I was alright at it, but there was a guy who lived across the street—Alphonso Morris—and I'd always hear this music playing from the front room of their house," Scrap recalls. "I just went over there one day to see what was going on over there. There'd always be people at his house and stuff.

"In the house, he had everything: deejay equipment, an 808, a beat machine, everything. And it was all organized. He asked if I knew how to deejay, and I told him I did. I didn't know what I was doing at all."

Scrap's neighbor knew that the then-10-year-old wasn't telling the truth, so he decided to mentor him.

"We sat on his bed, and he had me to pick out what records he would play, and I'd watch how he'd move the pitch control and all the other stuff," he says.

Most of the music the experienced deejay and his protégé were spinning was disco. This, little did the deejaying novice know, was the most challenging music to learn to spin. "If you were a disco deejay, you could do anything. It's the hardest thing to spin," he says.

Putting Things Together

But Mississippi wasn't completely foreign to the northern boy. He was born in a small community outside Starkville called Crawford, but his parents moved to Chicago not long after he was born. Nichols spent time in the summers with his grandmother, back home in Mississippi.

When he arrived at Jackson State, he had no academic direction or ideas.

"I switched my major so many times. I did mass comm for a while because I was running with Brad (Franklin, aka Kamikaze), and that's what he was doing. So I wanted to do that," Scrap says. "But then I took a marketing class and found that's where my heart was. I could put things together that others didn't see."

He had, in fact, been doing marketing since his first deejaying gig when he was a mere 11 years old at the West side of Chicago's K-Town, a teen club; he wouldn't have been able to get in any other way.

"I was supposed to be home by 7 (p.m.), but I got home at 1 (a.m.) When I got there, my daddy was standing at the door. He was pissed," Scrap says. "I tried to make it better by showing him the money I'd made—I'd made $100. He said, ‘I don't care what you made!' (and) whooped my ass, then he gave me my money back in $10 increments, when he felt like it."

Even then, the pre-teen was spinning music that was uncommon for a youngster to familiar with.

"I played a lot of techno from Detroit, but I didn't know it. And a lot of house music," he says.

House music originated in Chicago, although there's an ongoing argument about its real roots. Househeads, as they're called, agree about a few things, however: Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy, both popular Windy City deejays (who deejayed at The Warehouse and Music Box, respectively) appealed to blacks and Latinos, those who lived in the city's projects, and heterosexuals and homosexuals alike.

"People didn't really party together back then, yet. Frankie Knuckles came from New York when he was 16, and he was used to that. So when people heard what he was doing (musically), it appealed to all kinds of people. He played to a mixed crowed. Gay and straight people partying together? That was something back then," Scrap explains.

The two deejays would blend together things you'd never expect to hear black deejays play—punk rock, Sting, The Police—with the "black music" of the day: Prince and Grandmaster Flash, for example. They'd both throw marathon parties, from 8 p.m. until 8 a.m. the next morning. Scrap was too young to go to their parties at the time, but their thumbprints on his artistry are undeniable.

Scrap quickly became known for reading a crowd well.

Terry Hunter, the now internationally recognized deejay and Scrap's long-time colleague and friend, says Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy were known for making people break down crying on a club's dance floor. Scrap, he says, is no different.

"He can make a crowd move," he says.

Hunter says he met Scrap when he approached him one night at a party he was deejaying.

"I had done a party on the West Side at a cub called Resurrection. The people from the South Side didn't really go over to the West Side back then. But Scrap was just following the music. It's always been about the music for him," Hunter says.

‘I Am a Little Arrogant'

As Scrap gained professional experience while at Jackson State, he decided it was time to hone his business acumen.

"At 11, 16, I just wanted to get out and do things. When I got to college, it was more about getting some money. I loved what I did, but I needed money!" Scrap says.

Those who'd been upholding the house-music banner in Jackson at house parties—Sleepy and Howie from Detroit, Low Down Len from Chicago, Mark Full of Flavor—were leaving. He left for a while, too. But Scrap says he knew there could be a place for him still in Jackson, if he created one.

He started throwing self-promoted parties at the now-defunct club Metro 2001 and deejaying at WJMI for a while. But after the station let him go, he started managing an artist, and immediately, Chris Lighty, owner of Violator Management Brand Asset Group, took notice of Scrap's style and passion.

"Chris was a millionaire by the time he was 18 (from working in the music industry), so for him to notice me was big. And we both knew that deejays need more exposure than working at radio stations," Scrap says.

Around the same time Scrap was building a relationship with Lighty, he also began to forge a relationship with Barak Records founder and CEO RJ Rice Sr.

"I was producing Kurupt, and he was managing him," Rice says of Scrap. "I liked what he was doing, and I like his patience. He's closer to me than some members of my actual family because of his loyalty.

Greater patience, in fact, is one thing Rice says he's learned from his relationship with Scrap.

"I'm from a different generation. This generation—the musicians—they're not so patient with their music. They throw it together quickly," Rice says. "In my opinion … it's more about the money for them than the craft. ... And I think Scrap has more tolerance, and he's patient working with people like that, and it's rubbed off on me."

Barack Records is known for their Slum Village trio—rappers T3, Baatin and rapper/producer J. Dilla (the latter two have passed away)—and its cult following among

other artists like Young RJ and their Grammy-nominated act, Dwele. Currently, the label is set to release an album, "Village Manifesto," July 27. Scrap spent seven months between Jackson and Detroit as the label worked to produce the album that's destined to become an instant classic for followers of Barak-produced music.

"We've got Pops from De La Soul, Fife from A Tribe Called Quest, Baatin before he died. I used to watch these guys when I was coming up," Scrap says.

And as Scrap Dirty works on this album, he works to stretch his experience further beyond only deejaying.

"It's important to wear multiple hats … to not work for anyone else. I think using ball as an analogy is the best way to explain it. Most players are going to flip teams, but the owner is still the same," Rice explains. "Magic retired; Kareem Abdul Jabar retired; and yes, they did make a lot of money. But they didn't make as much as the owner did. ... I think Rob is learning it's more important to be an owner, behind the scenes than only out in front because the career is longer that way."

Scrap still manages people, too. In fact, he founded and manages the 50-some All-Star Violator DJs. No easy task.

"Deejays like to be babysat. They're divas. ... That's just how we are. We get in clubs free, drink for free, and people notice us and treat us like superstars. You can get caught up in that, and it will hurt you," he says. "I never got caught up in the superstar stuff, but I am a little arrogant. I'll admit that," Scrap concludes, smiling sheepishly.

Add to that the three conference calls he has every Monday, Wednesday and Friday; the artists who frequently call to see what new music and beats he can send them; the record label executives who call looking to have their records broken on-air by specific deejays; daytrading Barak assets; deejaying gigs across the nation; local events like the well-attended, monthly "Spoken Word in the City"; the show he co-hosts, "True Soul Café," every Sunday from noon-3 p.m. on WRBJ 97.7; a 5-year-old daughter, Amber, who demands her father's attention; subtract an assistant, and you have Scrap: a busy, busy man.

"The music business stays slow," he explains. "You have to do a little bit of everything. You might get one big check from ASCAP or somewhere else, and you might not see another check for three to four months. Then one month, you may get seven checks."

While the money may be temperamental, Scrap's commitment to help others "come up" is predictable.

Kwasi Kwa, the current program director at WRBJ 97.7 in Jackson, grew up in the same neighborhood Scrap did in Chicago, was familiar with the deejay's sound and followed in his footsteps by enrolling at Jackson State University. While he was in school, he began interning at 97.7.

"It was like a reunion. … He showed me the ropes. I was on the street team when he was doing parties at Metro 2000 on Saturday nights," Kwa, says. "You hired him to be a deejay, and he was going to be the deejay and the promoter. He's put a lot of people on. … He sets you up to do what you have to do, but you have to be prepared for it."

As for his colleague's deejaying skills, Kwa says it's an experience unto itself watching Scrap deejay: "Have you seen him deejay? It's in his veins. It's almost like he gets an orgasm from playing the music. That's his high."

RJ Rice echoes that sentiment. "Most deejays are creative, but they're not visually creative. With other deejays, it's audible, and it's supposed to be. But you don't see anything. Scrap—you're going to want to look at him."

‘A Spiritual Thing'

Like most things, deejaying isn't as simple as it looks. But if you're watching a master, he or she makes it look like something anybody could pull off.

"It's a spiritual thing," Scrap says.

His friend Hunter says: "Anybody that can pick up a computer thinks they can deejay. They can't. You have to know how to blend the records. You have to read the crowd. It's not just about putting two records together. You (could) just use an iPod nowadays, if that's all it took."

"I have so much going on, and sometimes I get away from deejaying for a minute. When I do, I kind of get off balance, lose my center. I can't think straight. I need to get to a turntable and spin some records," he says.

And as for the lessons he's learned along his journey, Scrap says: "I've learned to listen. You can think you know everything, but there's always somebody else who knows more than you.

"I'm probably going to disagree with you right off, because I'm bullheaded," he admits. "But you've gotta listen. It's the only way you'll get anywhere."

For more stories on upcoming musical events, releases, and interviews, sound off over to the JFP's Music Blog and have some fun.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus