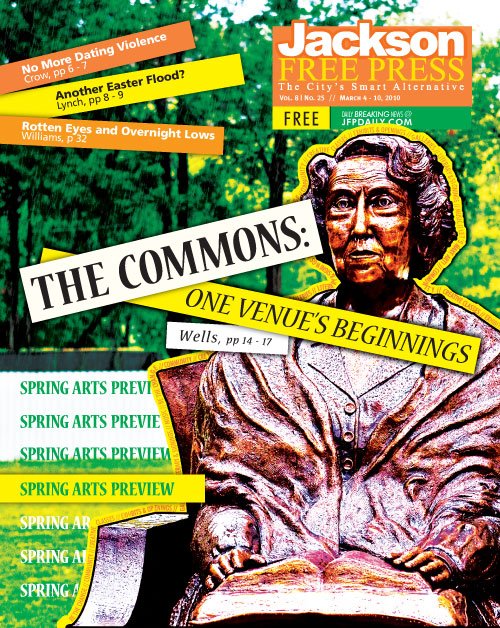

Under the quiet gaze of an oversized bronze statue of Eudora Welty, a friendly but insistent workman keeps asking Jonathan Sims what to do about the dishwasher. Sims can't answer right away. He looks down at the brick-imprinted concrete covered with wet leaves and concentrates.

Sims, 30, has a lot to think about. In a tan corduroy blazer, he looks more like a liberal-arts professor than the director of art events at the Commons at Eudora Welty's Birthplace. He's gentle and soft-spoken, quiet in his movements and thoughtful. He's always thinking things out.

"I've got other stuff," the workman says, spreading his hands out and smiling. "You call me."

As the workman walks off to the left, a plumber walks up from the right and hands Sims an invoice, then leaves. A handful of construction workers file back and forth behind Miss Welty's statue, working on an addition to the largest building. A little boy in yellow boots jumps into a small puddle left from days of rain.

Sims is patient and calm as he goes into the Common Grounds Coffee Shop, sits down and pulls out his brown date book. It reveals an upcoming drum circle, a bluegrass group, a poetry reading—but wait. He's not quite certain about these dates and needs to double check.

Sims has more on his plate than the average Renaissance man. Not only is he the events director at the Commons, he's also the artist in residence. His duties include scheduling arts events, promoting the Commons with a budget of nothing, building shelves and other basic carpentry like the movable bar in the gallery. He's a sculptor and a potter, and has a potting wheel and kiln on site, right under his apartment. He gives demonstrations of his work here from time to time. He's a musician, a graphic designer and a painter as well. He's also working on a master's of fine arts degree from Mississippi College.

He always carries with him his brown date book, always thinking about how to fit it all in.

Good Intentions

Between the yellow Victorian house on Congress Street where Welty was born, and just one block from the Greenwood Cemetery on West Street where she is buried, the Commons is a crammed complex of good intentions.

And in the middle of February, it unexpectedly closed.

It's only a temporary closing, insists Judith Thompson, director of the Commons who oversees all operations. A salad bar might be going in to attract a lunch crowd. The idea is for the complex to be open again by April 13, Welty's birthday, if not well before then.

David Morris and Joe Nassar own the property. The two are partners in the consulting firm of Morris and McDaniels, a company that tests and evaluates employees such as firemen and policemen internationally. They run that business out of the actual house Welty was born in; it's not part of the Commons complex. The Commons is a separate business that has to turn a profit to promote the arts, its primary mission, Thompson says.

"A sense of place is very important," Thompson says by phone. While she's home with a sick child. "We want a place for artists and musicians to share their talents, and to promote and highlight Mississippi artists. We're looking at the future and moving forward."

The nearby ominous and massive new Mississippi Supreme Court building overshadows the Commons at Eudora Welty's Birthplace. The huge temple of justice dwarfs the shrine to Jackson's patron saint of literature.

The small, understated sign in front of the Commons is like the subdued signs that accountants and lawyers put in front of their offices. Behind the simple, white wooden sign with black lettering is an oblong parking lot full of gravel and backed by a tall white fence. This, as it turns out, is not someone's private back yard. It is the almost-hidden entrance to the Commons.

Six buildings sit on the property in various stages of renovation and realization. The most startling is the Commons Hall, a new building sitting on the footprint of an older building. Its flat siding, massive columns and bulky banisters seem out of proportion with the historic neighborhood. Inside is a massive fireplace, large enough to walk into. Upstairs are three bedrooms, each with its own bathroom. The idea is that one day, visitors could rent these rooms.

"It's definitely a project in phases," Thompson says.

The Commons got two façade grants through the city of Jackson about 10 years ago to begin renovations. At a dedication ceremony for the large, bronze likeness of Eudora Welty in October 2008, visitors witnessed the "soft" opening of Tattered Pages Bookstore and Congress Street Coffee.

On any given afternoon this winter, the bookstore and the coffee shop have been empty except for an employee at the cash register. Occasionally, a lone customer sits in the corner, working on a laptop with ear buds in place.

It's not always this dead. Sometimes, Jamie Weems plays his mandolin with a Cajun band while couples sway in a contra dance. Kids bounce and squeal in one of those big jump machines. And for the $5 cover charge, everyone gets some gumbo. But that's not every night.

About once a month, a drum circle beats rhythms here. A writer's group hosts readings for its members. One group recently screened a new film here.

A blue grass group sang in the gallery one night, performing on the small stage built into the Victorian cottage's front bay window. This old house is in the middle of renovation with brown paper covering skeletal walls. It was meant to be a restaurant.

"That fell through," Sims says.

Now it is called the Gallery. The word is even on the door. But the un-insulated house isn't friendly to some works of art affected by the elements. Drawings by children at Davis Magnet School across the street are supposed to hang here soon. The teacher in charge hasn't called Sims back, yet, and he isn't sure what is happening with those plans.

Thompson knows a lot of people want to know what happened in the past: Welty's past, the property's past. For her part, she's interested in moving the Commons into the future, one phase at a time. As soon as the downstairs bathrooms and catering kitchen are complete in Commons Hall, she can start booking more wedding receptions and other functions in the space.

Right now, she is seeking a company to come in and operate a restaurant inside the Commons.

"We don't want to be a museum. We are a living, breathing, progressive venue," Thompson says.

A Sense of Timeliness

The yellow house at 741 N. Congress St., is not part of the Commons, although it is adjacent. This yellow house where Welty was born and lived out a sheltered childhood is home to the testing firm the owners operate.

A tall, imposing metal gate wraps around this house plus some adjoining properties across the street from Davis Magnet School. A woman closing the gate and headed to her car is suspicious of anyone approaching.

"This isn't the museum, you know," she warns. "No, you can't go in there,"

The gate isn't locked. A prominent plaque is on the wall by the front door, but no one could read it from the sidewalk.

This is what it says:

"This house, built by Christian and Chestina Welty in 1908, was the birthplace and childhood home of their daughter, Eudora. Many of the events memorialized in Miss Welty's book, One Writer's Beginnings, occurred here and take on a sense of timelessness for those who visit.

"David Morris and Joe Nassar purchased the property in 1979 for offices. Their restoration efforts reversed a tragic decline in the condition of the house and preserved it for its later acquisition by the Mississippi Writers Association to serve as the focal point for the Eudora Welty Writers Center. The foresight of the Mississippi Legislature is funding this project and the leadership efforts of Jo Barksdale, Writers Association Executive Director, combined to make possible this living tribute to one of Mississippi's greatest writers."

All Things Welty

Jo Barksdale's arms are full of notebooks, reports and documents. The woman whose name is so prominent on the plaque on the house at 741 N. Congress St. is wearing a red and black houndstooth jacket and comfortable jeans. She's a mix of old Jackson and laid-back southerner.

She's in front of the McDade's Market on Fortification Street, "Miss Welty's Jitney Jungle," where so many Jacksonians say they bumped into the famous writer buying her groceries and sundries.

Barksdale grew up in this part of Belhaven, and her family was friends with the Welty family and many other key Jackson families of the 20th century. She puts herself in the generation right after Eudora Welty's. On a drive around this part of town, Barksdale points out where Ross Barnett lived, where the Hederman family lived when they owned the daily newspapers, where she lived, the way she walked to school.

About 25 years ago, Barksdale wanted to find a brick-and-mortar home for the Mississippi Writers Association. The group was more than a club for published authors. It had plans and a vision for a Writers Center with workshops, lectures, public school programs and a resident writer or two.

As Barksdale began investigating the possibilities, she talked to Ken P'Pool at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

"Why not the house on Congress Street where Eudora Welty was born?" he suggested to Barksdale.

It seemed like a win-win situation. The house needed serious repairs, the neighborhood was in transition, the association wanted a home—Welty fans could rejoice.

Barksdale talked to David Morris, one of the owners of the then-dilapidated building, who said he loved the idea. She began developing a plan for a Writers Center complex that would take up much of the block on Congress Street where Welty's childhood home was located.

Her detailed plans included architectural renderings, layouts and grids, a 44-page business plan, a proposal for an annual Eudora Welty Film and Fiction Festival that would help fund operational costs of the center. A spa, a bookstore, and rooms for rent in a bed and breakfast would also generate income.

Her plans not only mapped out the potential complex; they spelled out staffing requirements and operational expenses. She touched on pricing strategies and restaurant marketing. She had charts projecting cash flow for the coming 10 years to prove to the Legislature she could make this Writers Center self-sufficient.

Barksdale took her bound reports and plans, with photos and charts and hard numbers, to the Legislature and succeeded in getting $2 million in funding for the Writers Center. The money was a non-interest loan to be repaid.

Miss Welty was present when then-Gov. Kirk Fordice signed the bill. Barksdale said Welty supported the project and liked the idea.

Suzanne Marrs disagrees. In her book, "Eudora Welty: A Biography" (Harcourt, 2005), Marrs briefly mentions the plans. "Barksdale hoped to transform Eudora's birthplace, which now housed Morris's consulting business, into a Mississippi Writer's Center and a tourist mecca," Marrs writes.

"Eudora, having already given her Pinehurst Street home to the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, did not want to lend her name to this new project but in attempting politely to withhold such support, she failed to say no in a convincing manner."

Barksdale says she has proof that Welty supported the plans and that Marrs doesn't know what she is talking about. Barksdale has letters and notes from Welty about the project and a picture with a note on the back from Welty thanking Barksdale for her efforts in creating a Writers Center.

She also questions Marrs' claims to be the ultimate authority all things Welty. Then she says she doesn't want to talk about Suzanne Marrs any more.

Welty made the front page of The Clarion-Ledger in March 1995 on the day Fordice signed the $2 million bill. Part of the money was to purchase the property and part was to implement the Mississippi Writers Association plans, Barksdale said. The paper said Welty supported the efforts to turn the property into a resource for writers. This was the high point of the project. It soon began to fall apart.

To get the money, several actions had to happen on time. The Legislature chose an appraiser to look at the property.

"The Legislature offered Dr. Morris the appraised price for the property, but he refused it," Barksdale reads from a handwritten statement she wrote on piece of loose-leaf notebook paper. "The Legislature could not (and maybe would not) appropriate more money for the purchases. The Mississippi Writers Association didn't know that Dr. Morris planned to hold for his price."

Without the property, the vision of the Writers Center died. The Eudora Welty Film and Fiction Festival died, too. The first one took place in 1996. The plans Barksdale made included the Junior League taking over the festival. A second festival never happened.

Even the Mississippi Writers Association died. Its membership had grown to about 800, but as the project died, interest waned.

"I don't know where the money to build Dr. Morris' project is coming from or what his plans are, or if the Legislature is funding his project," she says, still reading from her handwritten note. She continues reading:

"Even though I designed the original plans for a statewide Writers Center and had spearheaded the projects in connection with it, Dr. Morris has never contacted me about his plans. He, of course, knows ours. We couldn't gain entrance to his property and raise funds without his complete cooperation."

Barksdale says Welty never wanted a museum made out of her childhood home, and all the players agree with that idea. Everyone wants to honor her desire to keep her birthplace a living, breathing office building full of work and utility.

Welty once visited the home of a well-known author in the midwest whose home had been turned into a museum, Barksdale says. A stuffed dummy sat in the chair, replicating the author. Welty was horrified.

Driving around the temporarily closed Commons, the car slows down just past the Ole Tavern on George Street, which in Welty's childhood had been a neighborhood grocery store, rumored to hold a brothel upstairs.

That's another story.

Through the tall metal fence, Barksdale sees the massive bronze statue of Welty in the center of the complex. It's the first time she's seen it.

"Oh, no," she says. "She wouldn't like that at all."

For All the Arts

David Morris, who owns the property, agrees. Welty would not have approved of the statue. Other than that, he thinks she would have liked everything else developing on this corner of George and West streets.

"Miss Welty and I had several conversations of what vision she would be comfortable with. We've been pretty true to what she wanted," Morris says.

The $2 million the Legislature approved for the project in 1995 would have been nice, but Morris contends that it was the state that didn't want to pay the appraised value of the property. Morris says he asked for three appraisals from different sources.

At some point, it became clear it wasn't going to happen.

He says he heard of discontent within the Mississippi Writers Association, but doesn't elaborate.

Sometime after that, while talking to Leotyne Price's brother, George Price, Morris says he had an epiphany. He was explaining the concept of the Writers Center to Price.

"It should be for all the arts," Price said.

"And he was right," Morris says. "It's for all the arts."

He and his partner Joe Nassar are funding all the improvements and additions. He says the two facade grants are the only ones the Commons got.

Morris wants to restructure the hours the coffee house and book shop are open so the business side of the Commons can get a better return. He says the temporary closing is just until he can install the soup and salad bar, but he doesn't have a definite date for a reopening.

He's also expecting the final touches on the Commons Hall soon so it can be rented out for social functions.

"Wedding guests could use the bedrooms upstairs," he says.

Finding a local restaurant to come into the complex and complement nearby Two Sisters and The Tavern is another goal, one he sees realized within a couple of years. He also wants to have a farmer's market and festivals and lots of events. What he doesn't have is a specific time table.

"We're in no rush. It's like the Oriental saying: We have a long time to get it right. It won't be done in my lifetime," Morris says.

The Spoken Word

Janine Jankowitz, 23, holds a Writers' Spotlight periodically at the Commons. Her day job is with the Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Her passion is writing.

The Writers' Spotlight is a chance for writers like herself to perform their works in front of an audience. It's a little different from an open-mic night where anyone can get up and read who-knows-what. Jankowitz selects writers to perform, striving for an equal number of recurring and new voices. There has been four of these events so far.

"I was so happy when I heard about the Commons. And I heard Eudora Welty's name, and I thought, 'she's a writer,'" Jankowitz says.

"It's a wonderful opportunity. It's free, it's beautiful, and they've been open to having us. They often will contact me and ask when the next Writers' Spotlight is. It's inspirational to be around other people in the arts."

The next Writer's Spotlight is scheduled for March 27 at 7:30 p.m.

The future of the Commons seems uncertain with the temporary closing and organizational questions lingering.

Barksdale is skeptical of the funding and wonders how the private company is building and renovating the complex. Sims, the artist in residence, says scheduled arts events will still happen and he will schedule even more in the future, even though his promotions budget is limited to word-of-mouth strategies. Thompson says the complex is a huge undertaking, and the owners are slowly implementing new money-making elements into the Commons.

"It is a private business. Obviously, we can't operate at a loss. Our hope is through these means to support the arts. We're more in the spirit of promoting the arts," Thompson says.

Across the street and up the hill is Eudora Welty's grave in Greenwood Cemetery.

A large cedar limb fell recently, just a few feet away from her tombstone. On her grave marker, an engraver inscribed passages on the front and the back of the stone. On the front is a quote from "The Optimist's Daughter,» the 1973 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Welty wrote. The passage reads:

"For her life, any life, she had to believe, was nothing but the continuity of its love."

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.