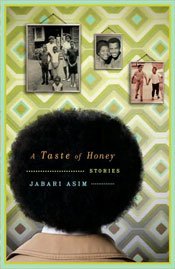

Sometimes I read fiction that I can't accurately describe without sounding like I'm shilling for it. Jabari Asim's "A Taste of Honey" (Broadway Books, 2010, $13) falls into that category. A journalist known primarily for his work in politics and black culture ("The N-Word," 2007; "What Obama Means," 2009), Asim has produced a first volume of fiction that is as potent and memorable as anything else you'll read this year. It will probably be another decade or two before Asim's fiction becomes essential reading in world lit circles, but I believe it will. This anthology is already a literary classic; when it is acknowledged as such (and it will be), that will be a formality.

Dialogue, characterization and little else drive this collection of 16 lightly connected short stories centering on the lives of people living in Gateway City (a common nickname for Asim's hometown of St. Louis) during the summer of 1967. The plots are simple, the scenery sparse, the style breezy and conversational. This is a nude figure study of the African American experience—very vivid, very focused, very full of life—and while it never blinks, it never lingers, either.

And no character just has a story. Lifelong friends Rev. Miles Washington and Ananais Goode, the preacher and the gangster who reappear throughout the anthology, represent different paths to power—both forged in resistance to white violence and racial terrorism. So there is something that should feel contrived about their backstory ("Ashes to Ashes"), but it doesn't; it rings true. Maybe it's because the histories of oppressed communities are full of stories about unlikely alliances that worked or maybe it's just because Asim describes the two characters in such realistic terms.

The author tells most of the stories from the point of view of 9-year-old Crispus Jones, who is shy, feels both awkward and awkward-looking and idolizes his cool and attractive older brothers, Ed, 17, and Shom, 12. His life rushes through a crazy environment that might have destroyed his innocence, though he didn't really have all that much to start with and, ultimately, makes him an extremely wise and perceptive young man. Crispus, like Asim, is an observer of human nature; he doesn't actually do much in these stories, but his eyes and ears give him an active presence, a sort of literary quantum-observer effect. Most of all, he learns—and he's such a well-written character that we can't help but learn, too.

What makes the stories particularly effective learning tools for Crispus, and for us, is the way they connect the abstract violence and interpersonal drama that we mostly just hear about, with the bottled-up tensions that we encounter in our everyday lives. Most literature, even great literature, seems to take place in its own world. But because real people who behave in real ways inhabit Asim's stories, the events that unfold make a certain amount of sense and even start to look disconcertingly familiar.

It's hard not to read some of these stories and not look differently at the family in line in front of you at the grocery store, or at the cracked glass on the windshield of the pickup truck at the gas station. It infuses everyday experience with dramatic arcs, giving every stranger a backstory and every effect a cause.

It reminds us how messy reality is.

Reviewers of this book tend to focus on the historical significance of its stories. Lynna Williams at the Chicago Tribune, for example, writes of how the stories "take us inside the life of a family and community in a tumultuous time," and author Chris Bohjalian writes of how "all of the hope and violence and seismic change that rocked the cities that summer ... [is] all beautifully rendered." I don't doubt its efficacy as a time capsule, but the stories in "A Taste of Honey" have a more universal literary significance. This is, to a certain extent, what life has always looked like, what it looks like now and what it may always look like. Like all great literature, it's bigger than history.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus