Kelsey Ann Jackson threw up. The thought of going to school that morning made her sick. She cried about the mean girls she would have to face in her sixth-grade class. After her mom dropped her off at her grade school in Brookhaven, Jackson walked as slow as she could to her class, dreading the coming ordeal more with each step.

The cruelty had started back in fifth grade, and no one really remembers why now. Jackson sang during an assembly in front of the entire school. After that, the cold shoulders and the intimidating looks started. Rude comments, whispered insults and wild rumors began with a group of girls who had once been friends. She never got to spend the night at slumber parties, except one time when the girls invited her over just to berate her and ridicule everything about her: what she wore, what she sang, how she acted.

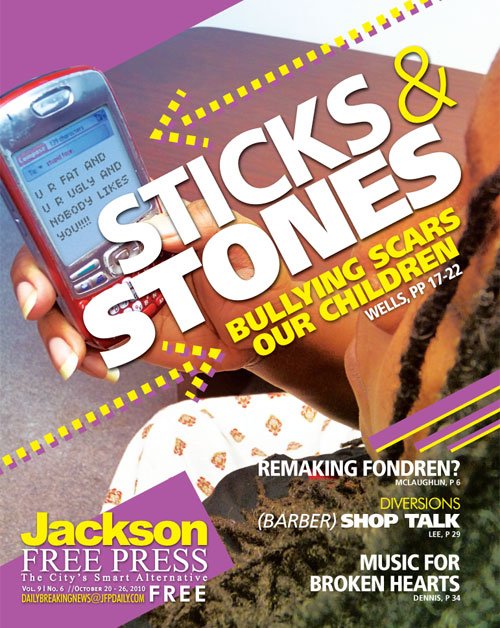

They wouldn't let her sit with them at lunch. They eventually enlisted the sixth-grade boys in the ongoing exclusion and dirty looks. This was about the time the text messages started. She started getting texts with cryptic insults like, "Kelsey, is it true? Did you really do that?" And then there were blunt ones.

"Whore."

It made her throw up.

Now a confident and mature college freshman at Ole Miss, Jackson confronts young girls who bully other girls and challenges the ones who are bullied to end the madness. She started a program, "Mean Girls Aren't Cool," and speaks to groups ranging from small Girl Scout troops to the National Conference on Girl Bullying this summer in San Antonio, Texas.

"Take up for yourselves and others," she said. "When the bully realizes you aren't going to put up with it, they'll stop."

Jackson, 18, came last month to the Anti-Bullying Youth Leadership Conference in Jackson specifically to have a word with the seventh-grade girls attending.

"How many of you have been bullied? Raise your hands," she said. Most of the 12-year-old and 13-year-old girls in the room lifted an arm.

"How many of you have bullied someone else? Tell the truth." She paused. Hesitant arms went up again.

"A lot of you who said you were bullied also raised your hands. Why would you want to do that, after you know what it feels like?"

‘Save a Life'

Jervia Powell, 12, knows what it feels like. Some mean girls in her history class last year bullied her until she cried. She still remembers their taunts. "They were messing with me, saying I was wearing the same shirt every day," she said.

It made her cry more than once. To an adult, that kind of teasing seems silly and easy to ignore, to a child it can be devastating.

Jervia, a seventh-grader at Woolfolk Middle School in Yazoo City, attended the Anti-Bullying Youth Leadership Conference last month. She was one of about 300 participants, most of whom were seventh graders. She is what Attorney General Jim Hood refers to as an ambassador in a statewide cause to stop bullying.

Hood used the conference to announce a collaborative campaign: Fear Stops Here. The attorney general's crime-prevention division and cybercrime unit are launching a website (http://www.fearstopshere.com) aimed at kids and public-service announcements jointly with the state Department of Education's Office of Healthy Schools. The new website includes a link to Jackson's site, http://www.meangirlsnotcool.com, as well as other sites loaded with information on how to stop bullying.

The Fear Stops Here campaign emphasizes the danger of cyberbullying. Text messaging is the new weapon of choice, and social networking sites such as Facebook are where bullies hang out, Hood said. And it seems to be a bigger problem with girls.

"Children will say things through text messaging and social-networking sites they normally wouldn't," he said.

The state has no centralized collection of data about the numbers of kids bullied in schools or how many of those bullied go on to attempt suicide.

"ullying (by females) is really increasing with the ability to cyberbully," Kelsey Ann Jackson said. "Our technology—the Internet, text messaging and cell phones—make it much easier to bully. Now gossip and meanness toward victims can be done in groups and with lightning speed."

Being the attorney general's daughter doesn't make life any easier for Rebecca Hood, 15, a sophomore at University Christian School. She pulled her hair behind her right ear while she held a microphone and faced a room of about 50 girls at the September conference.

"Just yesterday, me and another girl were in the principal's office," she said. "She decided to say things about me that were just wrong."

School's only been back in session for a couple months, but Hood has already come home crying a few times. Her message to the younger girls was to speak up when they see someone attacked, whether it is with closed fists, cruel words or hateful glares.

"Raise your hand if you would be the one to save a life," she said. Most of the girls raised their hands. Hood waited. The rest of the girls also raised their hands.

"I want you to save a life," she said.

Kelsey Ann Jackson encouraged girls to send her e-mails with questions. She shared her story about being bullied and how it affected her. She said she almost wishes at times her bullies had beat her up physically than socially excluding her and spreading rumors.

"I'd rather have bruises and broken bones. They heal," Jackson said to the room of girls.

A New Law

"Bullying has been around as long as schools have been around. It happens frequently, on a daily basis in most schools," Ryan Niemeyer said. A University of Mississippi professor who directs the Grenada branch of Ole Miss, Niemeyer is something of an expert on cyberbullying. His 2008 dissertation examined bullying laws in different states with a special attention to cyberbullying.

Earlier this year, Gov. Haley Barbour signed Senate Bill 2015 that requires all Mississippi school districts to adopt a policy regarding bullying or harassing behavior. The law went into effect this summer, and schools have until Dec. 31 to get policies in place.

Niemeyer, a former teacher in various Mississippi school districts, said the new law requiring districts to adopt bullying policies is a step in the right direction by defining bullying.

"Mississippi definitely needed that policy," he said.

Although bullying is nothing new, cyberbullying is rising at a fast pace. Schools need to address that reality, he said.

"Schools are used to dealing with situations that happen on campus. Bullying has been exacerbated by an increase in technology and social-networking sites. It can be a legal quandary when bullying takes place

off campus," Niemeyer said.

Schools are supposed to protect students on campus, but when cruel text messages and posts are sent at night from home to home, it's not clear when the school should get involved or how. Niemeyer said the standard applied today comes from the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court case, Tinker v. Des Moines. That standard is that there has to be substantial disruption at the school caused by off-campus harassment.

"There has to be a nexus or a connection. That's hard," Niemeyer said. "What's good is that (Mississippi) schools have to implement policies. They are not taking it lightly."

The school policies required by the new law will have to include a reporting process and proposed disciplinary actions. These are both good steps in the right direction, Niemeyer said. The state law also gives a much needed definition of bullying, which, in part, calls it "any pattern of gestures or written, electronic or verbal communications, or any physical act or any threatening communication, or any act reasonably perceived as being motivated by any actual or perceived differentiating characteristic" or "creates a hostile environment."

It's not a perfect law, Niemeyer said. It's vague in parts and is an unfunded mandate.

"Money is tight. An important component is you have to have training," he said.

Enter Bullycide

Psychologists have a new word for suicides that result from relentless bullying: Bullycide.

This year, several "bullycides" have grabbed national attention.

• Phoebe Prince, 15, hung herself in January after bullies electronically attacked her.

• Jon Carmichael, 13, killed himself in March. He got bullied for being too small.

Then, in September, five suicides happened in quick succession:

• Asher Brown, 13, shot himself in the head Sept. 23 after other Texas teens bullied him for being small, having a different religion and not wearing the right clothes.

• Seth Walsh, 13, hung himself from a tree in his backyard after other California teens taunted him for being gay. He didn't die at first. It took a week in intensive care before he passed away.

• Billy Lucas, 15, killed himself in Indiana. Even after he died, the taunts didn't stop. His bullies posted homophobic hate comments on his Facebook memorial page.

• Tyler Clementi, 18, jumped off a bridge and killed himself when his Rutgers University roommate secretly set up a camera and livestreamed a sexual encounter between Clementi and a partner.

• Raymond Chase, an openly gay 19-year-old college student, hanged himself in his Rhode Island dorm room.

A Cyberbullying Research Center study reports that all forms of bullying are significantly associated with increases in suicidal thoughts. Cyberbullying victims are almost twice as likely to attempt suicide compared to those who weren't bullied via text messages or the Internet.

"I hope we never have a child in Mississippi commit suicide," Hood told the middle-school students, teachers and parents who attended September's anti-bullying conference.

No one measures—and perhaps there is no way to measure—the number of kids who consider suicide or who change schools to escape harassment. No one is measuring how many kids who get bullied or leave school are gay or are being harassed because of race or religion. Robert Campbell, with Mississippi Department of Education's Bureau of Safe and Orderly Schools, said the new law doesn't require it, and that the state isn't tracking it.

Nationally, activists have pushed for more anti-bullying policies in schools. The "It Gets Better" campaign on YouTube has messages uploaded from celebrities and everyday gay people who dealt with bullying growing up. The Southern Poverty Law Center is providing a documentary, "Bullied: A School, a Student and a Case That Made History," to school groups across the nation. SPLC is providing the film at no charge and is encouraging educators to contact them.

"Unfortunately, organizations like Focus on the Family are pushing schools to ignore this crisis," reads an e-mail from SPLC promoting the film. "They say that schools should remain ‘neutral' and not mention gay and lesbian students in their bullying policies."

Niemeyer's review of anti-bullying laws reveals that most states do not break down victim categories by sexual orientation or race.

Only ten states have anti-bullying laws that enumerate categories of victims. Illinois and New York passed theirs this year.

"Most of the laws are unenumerated," Niemeyer explains. He goes on to say, "All students need protection."

‘Heart-wrenching'

Bullying will be a hot topic Nov. 5 and 6 at the Mississippi Safe Schools Coalition's third annual Queer and Ally Youth Summit at Millsaps College.

"Some of the stories are heart-wrenching," said Anna C. Davis, 27, a MSSC board member who lives in Hattiesburg.

Davis has seen insensitive language in college classes. A few years ago in an introductory sociology class at the University of Southern Mississippi, the instructor described something he considered silly and ridiculous as "gay."

"I approached him about it after class," she said. She told him she was gay and that she found the remark insulting. He promised her he would never do it again. She saw the professor again recently, and he made a point to tell her that moment had changed the way he looked at everything.

"This was in college at a very liberal university," Davis said. She can just imagine how hard it might be at some rural schools for gay teens without support.

When Audri Ingram was in seventh grade, she came out as a lesbian. When she was in eighth grade, she cut her hair short. Students at West Jones Middle School in Laurel started calling her names like "him," "it" and "he/she."

It wasn't just the kids. A teacher joined in the name-calling and cackling while Ingram was in earshot. The teacher found a letter Ingram had written to another girl and read it aloud to the class. A counselor at the school called Ingram's mother to break the news that her child was a lesbian. Her mom already knew, but the counselor crossed a line as far as Ingram was concerned.

"She outed me," she said. "I never went to the counselor again."

The name-calling followed her into the girls' bathroom where other girls berated her and would chase her out saying she wasn't allowed in there. Ingram wound up not being able to use the bathroom at school; she had to hold it. Every day, she risked harm to her bladder to avoid the bullies. Her mother eventually pulled her out of school and is now homeschooling her.

Ingram, 15, plans to finish high school this year and attend Mississippi State University next fall. She knows kids who cut themselves after getting bullied and harassed.

"If you are getting picked on, write down what is happening," she advises other teens who get bullied. She is the youngest member serving on the Queer Youth Advisory Board for the Mississippi Safe Schools Coalition.

Davis agrees with this advice but wonders if it fits every situation.

"I wish I could say go talk to a teacher, but not all students have that luxury. If you are working in a school, it should be your job to make school the safest environment."

Bullies, many of whom have been bullied themselves, need to see adults behave like adults to learn how to act, Davis said.

"There are no bad students," she said. "There are bad situations."

Punishing v. Criminalization

Another side of dealing with bullies in schools is how the system treats bullies. How do you punish them? How do you teach them to not bully? Many bullies have also been victims of other bullies. It's a cycle schools want to stop.

The challenge for schools is teaching bullies early to change behavior without labeling them as criminals. When it stigmatizes students, labeling is wrong, said Paula Van Every, director of Jackson Public Schools' Safe Schools Healthy Students program. Schools have good reasons for doing it, though. Van Every said it's an effective way to identify which kids need help and what kind of help.

Right now, each school district in Mississippi sets up its own policies for identifying bullying and how students are punished. So far, the cases aren't being forwarded to any centralized state agency.

"I don't think anti-bullying laws are meant to criminalize," Niemeyer said. "Some bullying might rise to the level of criminal behavior. Then that issue is best dealt with the criminal system."

Mississippi's new anti-bullying law focuses on prevention and identification at the school level. It also provides a way to help victims by shielding them from retaliation.

"It gives some direction, but it's vague," Neimeyer said. "It leaves it up to the school district."

The Southern Poverty Law Center is concerned that some kids might get labeled as criminals at a young age without learning how to change their bad behavior. Instead, SPLC encourages schools to find ways to keep kids safe and focus on solutions that are simple, common sense and cost-effective. Bullies need attention—the kind of attention that will ideally repair any harm done and includes everyone involved in a negative situation in resolving the conflict. That kind of "restorative" justice looks at what works best for the victim and the offender. Schools should use this kind of discipline, said Sheila Bedi, the SPLC deputy legal director responsible for juvenile justice and education work in Mississippi and Louisiana.

"Conflicts can be resolved," Bedi said. That's the lesson to teach all students. She also points to Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports, a systematic method and program available to schools.

‘Inside My House, I Was Safe'

Marye Runnels, a Hattiesburg mom who doesn't give out her age, homeschools her 13-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son partly because of her own experience enduring severe bullying. It was three years of abuse.

"When I was in the sixth grade, we moved from Clinton, Miss., to Minnesota. I was harassed about my accent. I was harassed because I thought some guy was cute. I was harassed because I had a different style of clothes. I got harassed in the locker room because I developed early and was a C cup while the other girls were still in training bras," Runnels said.

She went home crying two or three times a week for those three years before moving back to Mississippi.

"I can remember on the last day, walking home, being pelted with water balloons," she said. "I can only imagine how much worse it would be now with cell phones and the Internet. If I went inside my house, I was safe."

Even though she is homeschooling, Runnels' children aren't immune from bullying. Her son has gotten teased at church for preferring sports like golf over football. On a church trip, she witnessed another girl getting picked on and told her daughter to stand up for her.

"My daughter has a close-knit group of friends. I told her if I ever caught her picking on someone, there would be severe consequences," she said.

She thinks more parents should do the same. "Honestly, I think the parents need to play a bigger role. And a lot of parents are bullies," she said.

‘What's Going to Work?'

Last year, 24 students at Blackburn Middle School started down a new path in the Jackson Public Schools system. They learned ways to resolve conflicts, new ways to talk to each other and more detailed ways to listen and solve problems. Eight of those students will become student mediators in a new program unfolding this year at Blackburn.

Malkie Schwartz, director of community engagement at the Institute of Southern Jewish Life, worked with Blackburn educators to develop the program. Schwartz, 29, studied alternative dispute resolution in law school and said it can be applied to school situations. When she came to the institute and Mississippi last year, she asked people how she could best help the community. Blackburn educators then approached her about a mediation program.

"A lot of discipline is telling kids what not to do," she said. A peer mediation conflict-resolution program helps students discover what they could do instead.

An example Schwartz uses is hallway hostility. Every time a student comes into the hallway, the same kid bumps into him. They exchange funny looks. Then someone said something mean.

Through peer mediation, the students could each come and confidentially explain their side of the story. The mediators would ask open questions in nonjudgmental phrases and get both parties to express what they would like to see happen and acknowledge what their options are. They have the option not to talk to each other or the option to not be bothered by the funny looks.

"A student might say, ‘I'm willing to walk away' or ‘I'm willing to smile,'" Schwartz said.

Schwartz said asking them to smile at each other might be too idealistic and expecting them to become friends also might be asking too much, but peer mediators wouldn't hold the hallway bumpers to an unreachable standard.

"They would ask, ‘What's going to work?'" she said.

Last year's initial training focused on explaining the concept of conflict resolution. Students learned the technique of making "I" statements. Saying "I am upset" instead of "You upset me" can go a long way to reduce tension, blame and even funny looks.

"Conflict doesn't have to be negative," Schwartz said. "It can be a learning experience."

‘Tell a Trusted Adult'

If you feel bullied, then it's bullying, the attorney general told those gathered at September's anti-bullying conference. It's harder for parents, teachers and even other kids to recognize what's happening sometimes. If a child seems withdrawn, depressed or doesn't want to go to school, bullying can be behind the sadness. Adults need to pay attention to changes in behavior and intervene.

Jackson's presentation told girls how to not put up with abuse from bullies and how to intervene if they see another kid bullied. One of the biggest problems—and the biggest hope—is the bystander, she said. If more bystanders spoke up when they saw a bully make fun of a victim, the bully would likely stop the behavior. When a kid is getting bullied, she should find another kid to get a witness.

The attorney general said his advice for parents is to monitor computer and cell-phone use closely. If parents are paying for Internet access and cell-phone minutes, don't worry about a child's right to privacy, Hood said.

"Know their passwords," he said.

If text messaging gets out of hand, Hood suggests taking the cell phone away.

Part of the new Fear Stops Here campaign includes an anonymous hotline (866-960-6472) kids can call to report bullying. Mississippi Department of Education operates the hotline and encourages students to call.

If a kid feels bullied, he or she should tell someone. The mantra repeated over and over at the conference was "tell a trusted adult." The stigma of being a tattletale keeps many kids from telling an adult about the abuse. And sometimes when a kid gets the courage up to tell an adult, the adult doesn't believe it.

"Kelsey told a teacher," Jennifer Jackson, Kelsey's mom, said. "Her teacher didn't believe it because the girl was a good student."

"Queen Bee" bullies often are good students, well groomed and socially at the top of the pecking order, writes Roselind Wiseman, author of "Queen Bees and Wannabees" (Crown Publishing Group, 2009, $15). The book, a psychological look at girls who control cliques, was the inspiration for the popular movie "Mean Girls." A "Queen Bee" can frequently be a teacher's favorite student.

The advice for a bullied victim is to keep telling trusted adults until you find one who will listen. Kelsey told her mother and father. They went to the school, but nothing happened. The principal told them they would need to get a petition and get other parents to sign it. When the Jacksons did just that, parents of every girl in the classroom—except one—signed the petition complaining about the ringleader, the most "popular" girl. Even some boys' parents signed. The school brought in a therapist.

"That didn't do much," Jackson said.

Her parents believed her and confronted their neighbors, longtime friends, whose daughter had been part of a Queen Bee's campaign to ruin Jackson's life. The parents brushed off the accusation.

"It was more important that their daughter be popular," Jennifer Jackson said.

"Being bullied made me stronger," Jackson said.

"I like to sing and perform. I got involved in a show choir ... I realized I didn't need those girls. It raised my self-esteem," she said.

Jackson is planning to sing the National Anthem at the Atwood Music Festival this spring.

Audri Ingram intends to study sociology and social work at MSU. Her experience has forever changed her.

"Just because people aren't like you or are different, they aren't bad people," she said. "If you (pick on someone), you are taking someone's life in your hands."

‘I Wanted to Die'

‘They Accepted Me'

Finding Solutions

Looking for solutions to bullying? Get help and ideas from these resources.

Websites

• Fear Stops Here (http://www.fearstopshere.com). Fear Stops Here is a joint campaign of many state agencies and departments, including the Attorney General's office and the Mississippi Department of Education.

• Mean Girls Not Cool (http://www.meangirlsnotcool.com). Kelsey Ann Jackson's website focuses on female bullying. It has lots of statistics and resources, plus information on how to contact her to speak to groups or schools.

• Cyberbullying Research Center (http://www.cyberbullying.us). The Cyberbullying Research Center updates this site regularly with new research and information about the rise of electronic bullying.

• Suicidal Tendencies (http://www.family.samhsa.gov/get/suicidewarn.aspx). Pay attention to suicidal tendencies in your child. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration has a site listing important warning signs.

• Three Little Pigs redux (http://www4.va.gov/orm/Mediation/Pigs_all_scenes.swf). This short Flash animation shows what conflict mediation looks at the case of the Three Little Pigs vs. the Big Bad Wolf.

Book

• "Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and Other Realities of Adolescence," (Crown Publising, 2009, $15) by Rosalind Wiseman. Kelsey Ann Jackson's "Mean Girls Aren't Cool" program is inspired in part by the book. Available in bookstores and online.

Film

• The National Education Association-endorsed "Bullied: A Student, a School and a Case That Made History" is available free to schools from http://www.tolerance.org/bullied. "'Bullied' is designed to help administrators, teachers and counselors create a safer school environment for all students, not just those who are gay and lesbian. It is also intended to help all students understand the terrible toll bullying can take on its victims, and to encourage students to stand up for their classmates who are being harassed," according to the website. Comes with a two-part viewers guide that includes lesson plans and additional online resources. Limit one per school.

Hotline

• Call 866-960-6472 to report bullying in Mississippi schools. Callers can remain anonymous.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus