Thank God for the recession.

Wait: Let me start over.

As a fan of hip-hop and a lover of the culture, I consider the recession a blessing in disguise. See, hip-hop is a genre built on struggle. The truly great music of the genre has come out of great American tragedies.

Hip-hop itself was born when the powers-that-be removed programs that taught grade-school students how to play live instruments, forcing them to resort to making music from old records and their own made-up lyrics. It's a lemons-to-lemonade art form.

The war-torn and drug-riddled urban streets that came out of the crack era birthed the social commentary and hard-hitting lyrics pegged as "gangsta" rap. In the early '90s, N.W.A. shined a national light on the almost third-world conditions in Compton, Calif.

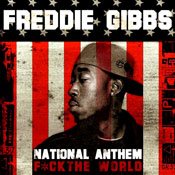

Over the last couple years, hip-hop artists have returned to grittier roots. The "gangsta" rap epicenter has shifted from Los Angeles, though, and moved to one of the hardest-hit victims of the recession: the Midwest. The automobile industry crash, political mischief, and the war-like murders going on in Detroit, Chicago and surrounding areas have made the Midwest ground zero for damage the recession caused. And the Midwest's hip-hop ambassador is Gary, Ind., native Freddie Gibbs.

Gibbs is a menacing figure when you first see him: square-jawed, droopy-eyed and gravelly-voiced. His songs are unapologetic, raw depictions of the dire straits the Midwest is facing. On "Murda On My Mind," Gibbs spits about Gary's "60 percent unemployment, why you think we selling dope?" His delivery is a millisecond slower than the members of Bone Thugs N' Harmony, and his voice is half an octave higher than Scarface's. But his subject matter and poetic attention to detail is the closest thing to Tupac we've ever seen and will probably ever get.

This is why Gibbs has been in every publication from The New Yorker to L.A. Weekly, without even releasing a full LP. His breakthrough mixtape "midwestgangstaboxframecadillacmuzik" made Gibbs a national phenomenon. And his latest project "Str8 Killa No Filla," accompanied by an EP named just "Str8 Killa," has created an undeniable musical force.

In the same way that N.W.A. narrated a Compton that was a microcosm of American's larger issues and failure in the black community, Freddie Gibbs is making the Midwest the new Everytown, USA.

"I'm from the ghetto, the ghetto, the ghetto ghetto / To make it out where I'm from, yes you gotta do something special / especially when we stressin' these economic conditions / conditionally causing us to cook the rock in the kitchen." Gibbs rhymes on the track "The Ghetto."

Gibbs' style is particularly catered to the South: His double-timed delivery is an aesthetic that has always caught on below the Mason-Dixon line. His hero is the late Pimp C, a Houston rap legend who is still considered a southern treasure. (Gibbs also shares Pimp's raw, not-the-most-flattering depiction of relationships with women—also another similarity between Gibbs and Pac.) And, most importantly, if anyone can relate to the violence and economic straits of the Midwest, it's the people who live in the South.

The rapper, who was briefly signed to Interscope before the label realized he was too rough around the edges and not marketable, has used the Internet and his uncompromising sound to become a major underground name in hip-hop. But to ascend to the upper echelon of superstardom, he needs a wider fan base beyond blog readers and Midwesterners. His emergence can and should begin by reaching the south. So give him a shot; you may even thank the high heavens for the recession, too, when you've finished listening.

David Dennis Jr., aka Jackson, is a rapper. Check out his music at http://www.myspace.com/jacksontherapper

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus