When a tree grows, it marks the passing of each year in distinct rings—thick rings represent the fat years when it grew quickly; thin rings for the leaner years when it barely grew at all. If Jackson were a tree trunk, its ring for 2010 would be one of the thickest, yet. Development in the city—especially redevelopment in downtown—has become more visible, and there's a sense of growing momentum, even a little confidence, to every announcement, every board meeting.

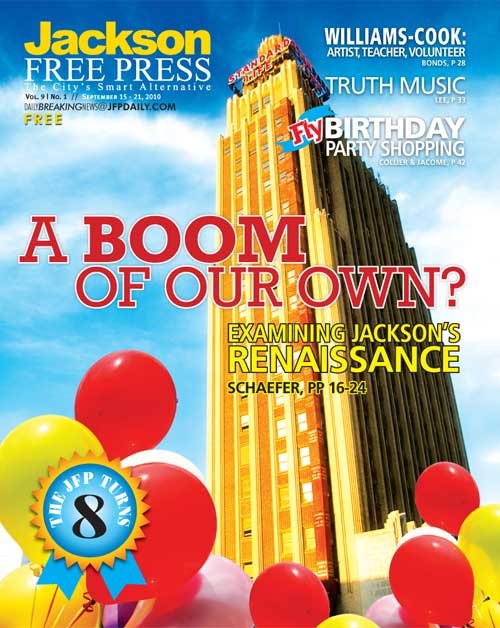

This year has seen the long-awaited renovations of two downtown landmarks. The Standard Life Building opened its doors to tenants Sept. 1. With 76 apartments and 2,671 square feet of retail space, the refurbished Art Deco high-rise adds significant space for the still-small number of professionals living downtown.

Arguably more symbolic, however, was the Feb. 1 opening of the King Edward Hotel. While the hotel is now technically a Hilton Garden Inn, the persistence of the King Edward moniker—and its iconic rooftop sign—is evidence of the building's importance in Jackson's self-image.

Like the Standard Life, the King Edward's tenants and its street-front bar are linchpins of Jackson's nascent downtown community, but the project's greatest contribution may be as a motivator.

The venture was a many-headed hydra: presenting challenges to developers' pocketbooks and political willpower. By conquering the beast, David Watkins gave Jacksonians and developers, especially, a shining example of how hard work and patience can prevail.

Jackson's challenge is to build upon its recent successes. High-profile developments such as the King Edward and the Standard Life prime the pump for further investments and other ambitious projects, but they also help reveal opportunities to fill in the gaps.

Watkins is at work on a row of retail and other businesses across from the King Edward—a health clinic, a wine shop, a deli—the stuff of everyday city life.

But he's also setting his sights high. Last month, Watkins unveiled a surprise proposal to redevelop the Metrocenter Mall into an entertainment venue with Jackson Public Schools' central administration as a kind of anchor tenant and automatic customer base, and an ambitious plan to construct an artificial canal and river walk that would drain into a 35-acre lake south of Court Street. He's also involved in Farish Street, much of which is slated (again) to come online this fall.

These future projects differ drastically, but what they share is a greater focus on the lives of people who already live in Jackson. And this is where they point to an important consideration in where Jackson goes from here.

If Jackson's redevelopment is to last, its progress must be sustainable and focused on creating and improving the communities that support the people who are here.

The Conventional Route

The Jackson Convention Complex opened in 2009 to considerable fanfare and high expectations. City officials boasted of the facility's full dance card—$1 million worth of bookings before the center even officially opened.

The JCC issued a report in January saying the center drew 128,590 people to 323 total "event days" last year, for an economic impact of $21 million. The center has nearly already matched those numbers this year. As of July 31, the convention center has drawn 124,945 people this year for 284 "event days," general manager Linda McCarthy says.

It's become clear, however, that the convention center could be doing more business. The vast majority of events in 2009 were single-day affairs, which usually drew local or regional visitors and are far less lucrative in terms of sales tax and commerce than events that require overnight stays. The convention complex estimates that attendees for a single-day event spends $70 per day, while visitors to multi-day events spend twice as much.

Downtown Jackson does not have the hotel room capacity to support large events, McCarthy says. Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. told the Jackson Free Press in May that building a 475-room hotel complex across Pascagoula Street from the convention complex could increase the center's business by 30 percent. So in June, the Jackson City Council approved a memorandum of understanding with Texas developer Mark Small to help fund the construction of a convention center hotel.

Progress on fleshing out that memorandum of understanding has slowed, but Johnson is adamant that the project will happen.

"From our perspective, the hotel is the big-ticket item that we need to be focusing on," Johnson said. "It's going to have far-reaching ramifications (for) our ability to collect taxes and to spur development in and around the convention center. We can only try to land one big fish at a time, and we're working as hard as we can to make sure the convention center hotel becomes a reality."

With that move, Jackson may have taken steps to support an already costly public investment. (City residents voted to approve a 1 percent sales tax increase to help fund the convention center.) But the push for a convention center hotel also underscored the similarity between Jackson's grab for convention dollars and efforts by other major American cities.

Since 1993, more than 320 convention centers have popped up around the country, representing investments of more than $23 billion by city governments. And, since 2000, convention space in the United States has increased 25 percent, as cities chase out-of-town dollars with ever-shinier boxes to host events.

With the supply of convention space outstripping demand growth for new centers, cities are continually trying to revamp their buildings. Houston expanded its George R. Brown Center by 420,000 square feet, but a 2006 audit showed that the center was generating a little over a third of the 600,000 room-nights originally projected. Washington, D.C., expanded its convention center at a cost of $850 million in 2003, but as of 2007, the center was producing 25 percent less hotel business than expected. For more than a decade, D.C. leaders have chased a convention center hotel to boost convention business, but the project has stalled thus far.

Heywood Sanders, a professor of public policy at the University of Texas-San Antonio, has criticized the convention center economy as an "arms race" that sucks in public investment and hardly ever generates the returns that center planners promise.

Still, with the center already built, the city has committed itself to a competition for convention money. Not only would larger conventions bring more visitors with coveted out-of-town dollars to spend, those larger conventions also help pay for the convention center's operations and the debt on its construction, McCarthy pointed out.

"You have to remember, too, that the operation of the convention center and the bonds on the construction are paid for by a hotel/motel tax and a restaurant tax," McCarthy said. "It's in our financial best interest to book events that fill up hotel rooms."

Business leaders appear allied with the city in backing the hotel. Jackson Chamber of Commerce President Jonathan Lee called a convention center hotel "pivotal."

"If we're going to see things happen downtown, if we're going to keep attracting people downtown, we've got to make that thing work," he said.

Arena Needs

A similar pattern exists in sports arenas. Like convention centers, arenas are massive structures that can inspire communities, offering residents a sense of pride and a photogenic new addition to the skyline. Also like convention halls, arenas often demand substantial public subsidies to stay profitable, and they tend to have a brief shelf life.

Some Jackson business leaders have caught the arena bug. Earlier this year, Downtown Jackson Partners tapped Populous, an internationally recognized consulting and design firm, to do a feasibility study for a downtown arena. Populous has a long track record, not only of studying the feasibility of these buildings, but of designing them as well. The company was formerly associated with HOK Sport Venue Event, another stadium design firm, and is famous for designing convention centers and sports arenas and stadiums.

While early discussions of an arena focused on giving Jackson the opportunity to attract a minor-league sports team, DJP Board Chairman Ted Duckworth says that he imagines the arena more likely serving as an entertainment venue. A sports franchise would take up too much of an arena's calendar with its home-game schedule, Duckworth says, when the real value of a downtown arena for Jackson would be its capacity to attract and host big-name entertainers.

"I don't think, from what I've heard, the desire is for any kind of franchise to call it home," he said. "From what I understand, that dominates too much of the schedule for available concerts and shows."

Duckworth is emphatic that an arena will help the city attract young professionals and build a vibrant nightlife. The Mississippi Coliseum is simply too outdated, with poor acoustics, to host things other than tractor pulls and horse shows, he says.

Lee agrees that an arena could be a "linchpin" for the city's development, but added that it is likely many years down the road. Downtown Jackson Partners and a coalition of business interests are currently seeking private funding for the feasibility study, DJP Associate Director John Gomez said.

Finding Role Models

It's not always bad to be a follower. Economic development is rife with talk about best practices and model examples, and for good reason. Bad development decisions are costly to private investors and often to taxpayers, too, so it makes sense for a city—especially one that often lags behind, like Jackson—to learn from the mistakes of other cities.

Emulating successful cities is a tricky proposition, though. Downtown Jackson Partners has organized fact-finding trips for developers and business leaders to other successful cities in the region: Little Rock, Ark., Baton Rouge, La., and Chattanooga, Tenn. When they return, they are full of ideas.

Little Rock was in part the inspiration for DJP's arena feasibility study. The 18,000-seat Verizon Arena, built in 1999, hosts the Arkansas Diamonds of the Indoor Football League and has hosted NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament games and Bruce Springsteen concerts. It may not be the best model for a downtown arena, however. Former DJP President and current executive director of the Memphis Airport Area Development Corporation John Lawrence says that its location across the Arkansas River from downtown Little Rock has been a liability.

"The problem with that arena is that you can see it from downtown, but there's a river in between," he said. "They don't get a lot of the foot traffic that they really should. With a facility like that, if you're going to depend on your major tenant being some sort of minor-league team, that has about a seven-year lifespan."

Because the economic boost from an arena is temporary, it is essential that smaller-scale development around the arena move in to make the project sustainable over the long-term, Lawrence says.

On the trip to Baton Rouge in 2009, Lee was captivated by that city's Shaw Center for the Arts, a private-public partnership involving Louisiana State University. The multi-purpose downtown facility, with retail, restaurants, performing arts and museum space, was an inspiration, and Lee, along with others, began dreaming of how to transform the Mississippi Arts Center in a similar fashion.

The problem, however, is financing, which Lee says is simply unfeasible in the current economic climate.

Chattanooga has also offered inspiration to some Jackson developers, as a prime example of a city revitalizing itself by reorienting development around its river. Beginning in the 1990s, Chattanooga's city leaders started transforming the city's moribund riverfront into a stretch of public parks and commercial and residential development. The area now boasts a movie theater, a children's museum and the Tennessee Aquarium, the largest freshwater aquarium in the world.

Most media coverage of the DJP Chattanooga trip focused on the city's use of its waterfront. "Every city we've been to has riverfront (development)," The Clarion-Ledger quoted DJP President Ben Allen as saying. "We've got (practically) nothing on the Pearl River."

David Eichenthal, a former chief financial officer for Chattanooga, sees a slightly different lesson in his city's resurgence. Eichenthal, currently the president and CEO of the Ochs Center for Metropolitan Studies, which focuses on development policy in Chattanooga, assessed the city's comeback in a 2008 Brookings Institution report.

"The transformation of Chattanooga during the last quarter century is a testament to a process more than any single investment in physical infrastructure," Eichenthal wrote.

"An aquarium or a park is no silver bullet to reversing the economic fortune in every community. ... The ‘Chattanooga way'—public private partnerships, strong planning, bold implementation and constant input from the public—could be replicated in other communities lacking the natural assets possessed by Chattanooga."

Lawrence says that Chattanooga's redevelopment is exceptional for its focus on the city's existing population. Developers geared their projects primarily toward serving the people already in Chattanooga rather than chasing out-of-town visitors, he says.

"Their philosophy has been: ‘We're going to create the best Chattanooga we can. We're not necessarily doing this to attract people from different places,'" Lawrence said.

Development for Chattanoogans can still look a lot like development for tourists, though, Lawrence concedes. The Tennessee Aquarium brings in considerable tourist revenue, and it has an obvious model in the National Aquarium in Baltimore, Md. Chattanooga also benefitted from the local Lyndhurst Foundation, founded by Coca-Cola heir Cartter Lupton, which funded planning and development efforts in the city's downtown.

Lee says that Jackson has the ability to create its own authentic renaissance. Developers here don't need to copy other cities' attractions, but they can emulate their methods.

"What you can copy is the financing structure," Lee said. "Banks are generally comfortable with what banks are comfortable with. It's not necessarily making their project work here. ... We don't have a shortage of ideas here. ... There's a shortage of money."

Stones Unturned

Ironically, the recession that has sounded like the death knell for some American cities has actually revealed Jackson's resilience and possibly improved its reputation. Jackson has picked up a number of accolades in the past year for weathering the recession relatively well: The Brookings Institution's Metro Monitor picked Jackson in June 2010 as one of its 21 strongest metropolitan areas, recognizing the city's relatively small dip in employment and its solid economy. Yahoo! Real Estate put the City With Soul third on its list of "Best Bang For Your Buck" cities for its low cost of living and stable home prices.

The reason for Jackson's sturdy economy is, as most business leaders will tell you, its stable, three-part foundation of health care, education and government. All three industries are essential in both good times and bad.

"I hate to use this term, ‘recession-proof,' but the fact of the matter is, the health-care industry has not suffered along with other industries during this recession," Harvey Johnson said. "In fact, the University (of Mississippi) Medical Center over the last 18 months, has made (more than) 900 new hires. That indicates to us that we need to be paying closer attention to the health-care industries."

Lee believes that the city has yet to fully exploit two of those industries: education and health care. A recent study by the Hinds County Economic Development District estimated the economic impact of college students on the Jackson metro area at $3.5 billion. Almost 40,000 students attend the colleges, universities and community colleges in the metro area, yet the city has not begun to market itself as a college town until recently. That means building stronger ties between government, businesses, and Jackson's education and health-care institutions, he says.

Johnson said that his administration has only recently begun talking with health-care institutions about city support, but that one possible area could be the development of Woodrow Wilson Avenue as a "health-care corridor," incorporating the Jackson Medical Mall and UMMC.

The city is also working to develop more innovative support for development. As evidence, Johnson points to the opening of a Vowell's Market Place in the south Jackson location previously occupied by a Kroger grocery store. The city enticed Vowell's with a $50,000 grant. The incentive was "a new tool in the toolbox," Johnson says, created using U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development funds. Johnson expects the store to have between $8 million and $10 million in sales and generate over $100,000 in sales tax for the city in its first year.

Big-Ticket Inspiration

Duckworth says that the key to sustaining Jackson's growth is keeping a pipeline of projects in various stages of conception and completion. His own ambitious proposition, the District at Eastover, is stalled for the moment while he negotiates with the state for the northeast Jackson property. The Mississippi Legislature passed a bill this year authorizing the state to sell the old Mississippi School for the Blind and Deaf to Duckworth, but Duckworth says that the sale is still pending.

David Watkins, fresh off his successful completion of the King Edward and Standard Life Building has set his sights on the Metrocenter Mall. Watkins' plan calls for moving the Jackson Public Schools' administrative offices to the mall, to save the district money and act as an anchor for future commercial development. The JPS Board could vote to make the move during the next school year, but the later phases of Watkins' plan, including a movie theater and "water feature" are three to seven years from completion.

Watkins is also shopping another, even larger vision he calls Jackson Riverwalk and Town Lake. The project includes a mile-long man-made canal and a 35-acre lake in downtown Jackson, which would take at least five years to build.

Much like the King Edward and Standard Life, proposals like these generate excitement and spur other developers to dream up their own projects. When complete, they are a source of civic pride and cause for optimism.

"The question that I get most often from friends and strangers is, ‘When are you going to turn some dirt?'" Old Capitol Green developer Carlton Brown said. "After the King Edward opened up, people weren't so harsh in their questioning."

Jackson's growth is not simply a matter of giant steps taken every five years, however. The city is passing smaller development milestones regularly. On the other side of the King Edward, unused storage space underneath the Mill Street viaduct could become an open-air market. Jason Brookins, executive director of the Jackson Redevelopment Authority, introduced the idea, called Union Market, in July and believes JRA could advertise for proposals by the end of the year.

The 34-acre Jackson Square shopping mall at Terry Road and Interstate 55 is currently only 20 percent occupied, but California-based developer Jessie Wright, who bought the property in February, has plans to bring a roller-skating rink, soul-food restaurant, grocery store and call center to the mall.

While ambitious, expensive proposals are less likely to find funding these days, it's still essential that developers have the ideas, Lee says: "They've got to be in the hopper. We've got to continue to look at those things even when the money looks slim. You think about how farther along we would be if we had more projects in the hopper when the (federal) stimulus act was passed."

Streets and Lights and Pipes

The pace of development is all the more remarkable given the persistent gloom of a national economy that makes banks and municipal government alike wary of loaning money for potentially risky projects.

Old Capitol Green prophet Carlton Brown has had to pursue zoning changes, draft a public-private partnership with the county and city, and secure financing for his planned 50-acre mixed-use development—no easy task in this climate, he says.

"We had to try to structure the financing in the biggest financial collapse since the Great Depression," Brown says. "So you stack all those things on top of each other, and I'm pretty pleased we're moving this fast."

Delays in financing have also slowed progress near Jackson State University, where the first phase of its University Place project—a four-story, mixed-use residential and commercial building—broke ground earlier this year on Dalton Street.

Financing for later phases of the development, which call for market-rate housing near the Terry Road roundabout, is still uncertain.

With the national economy still struggling, loans may remain scarce for some time, but Jackson also has a more immediate threat to redevelopment efforts.

Jackson's aging infrastructure is also "major impediment" to future development, Lee says. "You can't put up a 12-story building if you can't flush the toilet," he said. "It's a very, very real issue."

Old water and sewer lines have held up progress on Old Capitol Green for multiple years, according to Brown and his partner, Malcolm Shepherd. Full Spectrum is in the middle of negotiations with the city and Hinds County over their roles in providing infrastructure for the development. As Shepherd explains it, Commerce Street has never seen the density of development that Full Spectrum is proposing for that area of downtown.

"The nine-inch water line that runs down Commerce Street could not service one of the buildings we're talking about," Shepherd said. "We need a much bigger line. The 13-inch sewer line that services Commerce Street is under capacity for even one of our buildings. In one of those residential buildings, if everybody flushed their toilet at the same time, someone's going to

be unhappy."

The city's infrastructure needs also present opportunities, however. Rebuilding the city's thoroughfares and utilities can fundamentally change the way the city and future development responds to Jackson's population. Brown refers to this as "placemaking," creating public and semi-public spaces that promote the kind of informal interaction between citizens that strengthens a community.

"You need to have those sorts of places to create real community, because real community happens informally," Brown said. "The sort of isolation that was created by the cul-de-sacs of the suburbs worked against forming communities; when you don't know your neighbor, there's no place to gather. It doesn't take a huge investment to create these places, you just need to understand that the creation of those places is important."

Many of the South's iconic cities have these public spaces—like Savannah, Ga., with its 22 park-like squares—but Jackson has less of this available, Brown says.

Old Capitol Green's design is based around 14 square blocks, and nearly every block has an open-air courtyard at its center. The project also calls for a fountain and square at the intersection of Court and Commerce streets, and for an extension of the grassy median and bike paths along Commerce Street.

Street redesign projects in other parts of the city hold a similar promise of making the city more livable. After initial meetings between city officials and residents in 2001, the city has plans to begin preliminary infrastructure work on a redesign of Fortification Street by the end of the year. The redesign will eliminate one lane from the pothole-ridden commuter thoroughfare, creating a three-lane road with a central turn lane, wider sidewalks, decorative street lighting and underground utility lines.

The city has $8.4 million for the $15.5 million project already on hand and is requesting an additional $4 million from the Mississippi Development Authority. City Planning Director Corinne Fox said that the project would make the road more appropriate for the people that live around it.

"It makes (the street) compatible, so it's not just a major road running through the middle of the neighborhood, ...separating the neighborhood and creating a hazard," Fox said. "It's making it people-friendly."

The city is planning a similar project to extend the Metro Parkway, with its landscaping, wide sidewalks and bike paths, from its current endpoint at Wiggins Road to Ellis Avenue, Fox said.

The Mississippi Department of Transportation also awarded the city $2 million for improvements to sidewalks, street lighting and landscaping along North State Street in the Fondren area, a project that is under way.

Although they lack the glamour of restored old buildings or shiny new ones, infrastructural changes are the connective tissue that is essential to giving a redeveloped Jackson its own character.

"There's not a city in the country that you go to and leave thinking, ‘That was the greatest convention center I have ever been to,' because they're all pretty much the same place," John Lawrence said. "One might be a little nicer than the other, and Jackson's is really, really nice. But you go away thinking, ‘That was the coolest little restaurant I ate at.' ... Those are the memories you go away with, things that are authentic to the area, and that's the hardest thing to do. The mistake is assuming it will happen, if you build the big thing, because it will not happen by itself."

Progress, Progress, Progress

Waiting for the Convention Center Hotel

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus