The 1960's remains pivotal in Mississippi's bloody road to ethnic equality. Had it not been for a group of college students and a handful of volunteer organizations, though, Mississippi's leap forward may have been postponed for years.

by Byron Wilkes

September 29, 2010

The 1960's remains pivotal in Mississippi's bloody road to ethnic equality. Had it not been for a group of college students and a handful of volunteer organizations, though, Mississippi's leap forward may have been postponed for years.

During the summer of 1964, hundreds of college students joined even more Mississippi blacks to take part in the Mississippi Summer Project, known as Freedom Summer.

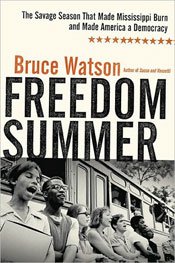

One of the most comprehensive accounts in recent times of this extraordinary and courageous effort is Bruce Watson's "Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy" (Penguin Group, 2010, $27.95). Watson's work gives a rigorous retelling of Freedom Summer, from the years and months preparing for the event, to its execution and the retaliations from white Mississippians that pervaded its duration.

The story arcs over the summer of 1964 and follows the tales of volunteers, teachers and those registering voters, as well as prominent figures in the movement, like Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer.

Watson's use of firsthand interviews with volunteers on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and black Mississippians impart the intricacies of the group's training process and what they expected coming to Mississippi versus what they experienced.

During the volunteers' first night in Mississippi, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner went missing after leaving Philadelphia in Neshoba County where they had been investigating a fire at the Mt. Zion Methodist Church.

Watson's sweeping retelling of the events that followed includes Rita Schwerner's poignant actions after learning of her husband's disappearance, including telling then President Lyndon Johnson to his face that he wasn't doing enough to search for the men.

Letters sent from volunteers to their par- ents reveal the extent to which these students and others were dedicated to the cause and Mississippi, as menacing as it seemed.

"... I sense somehow that I am at a crucial moment in my life and that to return home where everything is secure and made for me would be to choose a kind of death. ... I feel the urgent need, somehow, to enter life, to be born into it."

All in all, Watson's book gives one of the most intimate examinations of Freedom Summer this reviewer has ever perused. The level of detail and craftsmanship with which Watson tells the story of Freedom Summer bestows a version of Mississippi's past rarely told, and one that should be read by anyone who today enjoys civil rights in America.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus