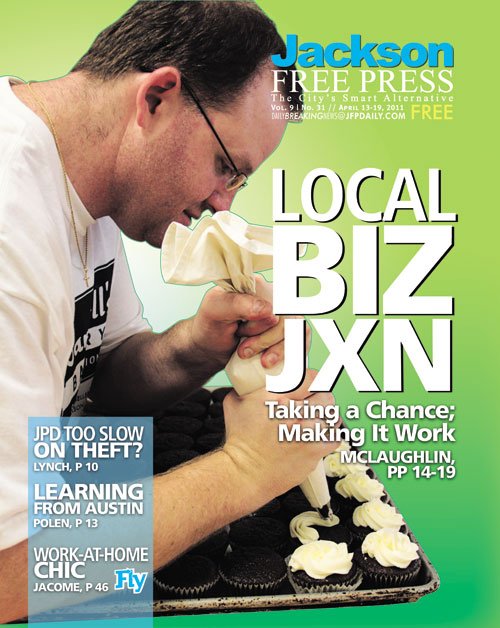

When Mitchell Moore was 4 years old, his parents gave him an Easy-Bake oven for Christmas and changed his life. He was fascinated by the way batter could turn into a smooth, fluffy cake and would spend hours perfecting his creations. The 38-year-old has been baking ever since.

In 1996 Moore started working as a pastry chef at Nick's Restaurant, then located on Lakeland Drive.

Moore left Jackson to work on a film set in Los Angeles in 2002, but came back in 2005 and worked a few jobs before he got an itch to go into business for himself. Because his specialty was cheesecake, he decided that if he could get local restaurants to buy his cheesecakes directly, instead of from distributors, then he would start a business in Jackson.

He decided to take his product to his former employer, Nick's. When owner Nick Apostle sampled Moore's cheesecake, he was impressed.

"It tastes better than what we are selling, and it costs less," Apostle told him in 2007. "It's a win-win."

As orders started coming in, Moore realized he had a problem. He needed a commercial kitchen with a mixer and larger ovens to fill all the orders. That's when Apostle made him a deal he couldn't refuse: If Moore made desserts for Apostle's new restaurant, Mermaid Café in Madison, then he could use the kitchen to operate his own business.

As word spread about Moore's cheesecakes, demand grew. Not just restaurants were buying from him, but people wanted his cakes for holidays and birthdays. He started looking for places to operate his own bakery, but nothing fit his budget. Almost two years after he started his position as pastry chef for Mermaid Café, his friend Jim Burwell, owner of Mimi's Family and Friends in Fondren, called him. Campbell's Bakery in Fondren was closing. Was he interested in opening it back up?

In a matter of days Moore formed an LLC and signed the lease to the building. A month later, on March 23, he opened the doors to his own business.

Supporting Small Businesses

Making the decision to open a business isn't one to take lightly. Forty percent of all new businesses close within their first year, writes Michael Gerber in his seminal business book "The E-Myth Revisited: Why Most Small Businesses Don't Work and What to Do About It," (Harper Collins, 1995, $18.99). The "E" stands for entrepreneur.

The city of Jackson approved 1,280 business licenses in 2010. As many chain stores and restaurants have moved to the suburbs, Jackson has become an attractive community for small, independent business owners.

Jackson Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. said the city has expedited the process of issuing business permits since he first took office in 2009. For example, the city has issued about 70 business licenses per month from December 2010 to February 2011, Johnson said. Jackson has also been able to expand its funding for small-business grants through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Community Development Block Grant program.

Recently, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed cutting CDBG funds by 62 percent—the largest cut to the program in its 41-year history. The program was designed to help municipalities shore up community services as well as economic development. To receive CDBG funds, cities must show that their programs benefit low-and moderate-income residents, prevent or eliminate blight or meet an urgent need in the community.

"We are providing a service that the community needs," said city of Jackson Economic Development Acting Deputy Director Mike Davis, who oversees the program. "It is very rewarding to know that as the result of these funds, over 200 jobs have been created."

The city offers three types of grants: the Storefront Improvement Grant; the Small Business Development Grant; and the Special Economic Development Grant. The city of Jackson awards the grants through an application process, and business owners must match 25 percent of the federal funds awarded.

In 2004, during his second term, Johnson established the Small Business Development Grant Program to provide business owners with operational and technological equipment upgrades such as computers, copiers and cash registers.

In 2010, the city expanded the grant program to include the Special Economic Development Grant. Businesses that make at least $1.5 million in facility improvements and create at least 30 full-time jobs are eligible for grants under this program. One business to receive a grant was Vowell's Marketplace, a grocery store in south Jackson on the site of an old Kroger, which is expected to bring 50 new jobs and $10 million in sales to the city.

Last year, 35 small businesses benefited from Jackson's grant programs. The city issued 24 small-business grants totaling $295,499; 10 Storefront Improvements Grants totaling $89,9330.60; and one Special Business Development Grant for $50,000.

"The funding we receive from the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Community Development Block Grant Program is vitally important in keeping these grant programs going," Johnson said in a January statement in response to Congress' plan to cut the program. "We implore federal decision makers to look at the jobs we have been able to create and save at the local level, as well as the success of the small businesses that have benefitted from this program. The numbers speak for themselves."

Davis said that his department reviews the applications and recommends the grants to the Jackson City Council's approval based on the promise of an applicant's business plan and the type of service provided.

If the U.S. House of Representatives had been successful, the city would have lost about $1 million from its CDBG budget, which Johnson says would have hurt the city's development. In addition to the business grants, CDBG funds also help the city provide infrastructure repairs, park and home improvements to moderate and low-income areas, and 20 nonprofit organizations in the city.

"All funds for these programs would have to be reflected in this major cut," Johnson said. "Some of the programs probably wouldn't survive. Not only would we have problems funding the economic-development aspects of our CDBG program, we would have problems funding other aspects as well."

The budget deal that President Barack Obama and Congressional leaders struck April 8 cuts just 11 percent of funds from the national CDBG budget. City spokesman Chris Mims said he did not yet know how those cuts will impact Jackson.

Making His Own Way

It's March 21, and Moore is a week behind his scheduled opening date for the new Campbell's Bakery. As he gets ready to open his store, Moore is still working as a pastry chef at Mermaid Café until the restaurant fills his position. The night before, he got home at 2 a.m. and woke up at 6 a.m. to prepare Campbell's for opening. Working 14-hour days has become standard these days.

Now, with a payroll and rent to make, Moore is eager to open, but shows few signs of stress. With the help of his wife, Natalie, and community members, Moore has transformed the interior of the bakery, which has been a Fondren staple since the 1950s. When he got word that the contractors who had started the renovations were behind schedule, Moore put out a call to the community and family members. They showed up in droves to help him open.

His wife, who works full time as a dental hygienist, has been helping him on her off hours.

The walls now have a fresh coat of light-blue paint and new baseboards. Moore has added a cake-decorating room with windows where colorful cookie cutters hang on hooks. Bright green and orange chests that Moore bought from N.U.T.S. serves as the bakery's front counters next to new pastry cases. Moore will soon hang paintings from Jackson artists such as Josh Hailey on the walls.

"We wanted it to be shabby chic with mixed-matched plates and mugs to make it feel homey and welcoming," Natalie Moore says as she preps the front of the store for more painting.

At 7 p.m., Moore is perfecting a coconut cake. "I've never made one of these before," he says as he puts icing on the four-layer cake.

The bakery came equipped with ovens, a mixer, two freezers, a mop sink and a walk-in fridge. The tricky part has been learning how to operate the ovens that are almost as old as Moore. The deck ovens open like drawers and once served as pizza ovens in an old Shakey's Pizza location now occupied by Fondren Guitars nearby.

Ron Chane, owner of Swell-O-Phonic, stops in to say hello to his new business neighbor, and Moore points to the floor of the oven to show how it slants. Moore spent the better part of his work day using a jack to move the large ovens so that his cakes would turn out even.

"You should have just tilted it even more, so the cakes would be tilted," Chane, who designed T-shirts for Campbell's', jokes. "It kind of makes it weird, just like Fondren. You could call it Crooked Cakes in Fondren."

"You're the idea man," Moore says, pointing to Chane.

For years, Moore had been saving money to start his business because he did not want to begin by taking out a loan and being in debt. He partnered with former Campbell's owner Robert Lewis, who still owns the equipment. Despite his savings, Moore never thought he would be able to have such a well-equipped bakery.

Moore admits that he underestimated what it would take to actually open a business, but says he should have known better. His father, Delton Moore, who once owned a pharmacy in south Jackson, gave his son three pieces of advice about opening a business: "It's going to take twice as long as you think, and it's going to cost twice as much.

"And finally," he said, pausing, "you are not the exception to the rule."

Moore wipes the sweat off his brow and laughs.

"I still thought I was the exception," he says. "I had it all planned out. I had a list of things I would do every day to open on time. ... I thought I could do all this work all myself."

Moore's father and his mother, Peggy, show up with Chinese take-out. After the family sits down for a meal at the cake-decorating table, they roll up their sleeves and paint furniture until late that evening.

The 'E-Myth'

After a Mississippi Department of Health inspector gives Campbell's the seal of approval, Moore opens his doors March 23. But nothing could have prepared him for what happens as soon as he turns on his storefront sign.

The night before, a reporter from WAPT-TV had stopped by the store while Moore was preparing to open, and interviewed him about reopening the historic bakery. His TV appearance helped get the word out, and a steady stream of customers fill the interior of the bakery on opening day.

Several customers and Fondren business owners who walk through the door exclaim how happy they are that the bakery has signs of new life. Moore, who showed up at 2 a.m. to bake, greets customers while refreshing the pastry case as his wife runs the cash register. By 2 p.m. Moore has run out of petit fours and cheesecakes and is on the verge of running out of cake pops, small bite-sized pieces of cake on sticks.

"We expected this," he says. "But we just didn't have enough time to prep."

Gerber, author of "E Myth Revisited," would say that Moore is in his infancy stage of business in which the work can consume a person, though they do it with a smile.

The majority of small business owners start their business so they can be their own boss and do what they love, but despite their hard work many businesses still fail. Business owners must take on three personalities to be successful, Gerber writes: the technician who enjoys working and getting the day-to-day operations done; the entrepreneur who is the visionary and the dreamer; and the manager who focuses on planning and putting things in order.

Instead of evenly dividing those roles, most small-business owners are only 10 percent entrepreneur, 20 percent manager and about 70 percent technician.

"You're not only doing the work you know how to do, but the work you don't know how to do as well," Gerber writes. "You're not only making it, but you're also buying it, selling it and shipping it. During infancy, you're a master juggler, keeping all the balls in the air."

But when those balls fall, which they inevitably will, Gerber says, that's when a business must transition to adolescence, or it will fail.

"To be a technician is simply insufficient to the task of building a great small business," Gerber writes. "Being consumed by the tactical work on the business ... leads to one thing: a complicated, frustrating and eventually demeaning job."

Transitioning Out of Infancy

One year ago, Chris Paige opened Custom Cuts and Styles, a barbershop in south Jackson on Terry Road, with one hair-cutting station and a handful of loyal clients. Today, he has three full-time barbers, six cutting stations and a styling room for women.

The afternoon of March 30, Paige wraps up a long day of setting appointments, cutting hair and managing his business. A sign that reads "no profanity no cussing zone" hangs next to a 42-inch flat-screen television and his 2011 Jackson Free Press "Best of Jackson" award for Best Rising Entrepreneur.

The 32-year-old Jackson native opened the shop to help revive south Jackson's business community. After he opened, he applied for a storefront improvement grant. With the $12,000 the city awarded him, he got a 75 percent refund on equipment such as styling stations, the television, shampoo bottles and chairs. The grant is only eligible for equipment purchases.

After working a full day, Paige heads to the Academy of Hair Design where he teaches barbering four nights a week.

Paige recently received approval for another grant through BankPlus, which he will use to purchase a sign, and office furniture and equipment, including a computer.

After working in various barbershops for 12 years, Paige took out a small business loan so he could open his shop. He went door-to-door with flyers in the neighborhoods that surround his business to attract new clients.

Paige says the city's support helped him transition and expand his business. He is now eyeing a possible location for a second future barbershop.

With an unstable economy, Paige said he has had to work hard to keep up his client base and is always looking to improve his services—which are somewhat recession-proof, but not entirely.

"(Customers) come and see you depending on if they have a job or not," Paige said. "With the economy down, I did see a decline in my customers. Not because they didn't want to come, but because they couldn't come. You can't just be comfortable with the customers that you have; you have to always try and get new ones in."

As businesses grow and change, they must learn to adapt and mature, Gerber points out. A mature company is founded on a broader perspective. Instead of leaving decisions up to chance, a business successfully grows by knowing where it is and where it needs to be.

Cities such as Little Rock, Birmingham and Baton Rouge have created business incubators to help entrepreneurs transition through the various stages of owning a business. An incubator essentially is a hub where entrepreneurs rent space, and receive resources and business-growth assistance from professionals.

In the fall of 2010, Downtown Jackson Partners provided start-up funds for Jackson to start a business incubator. Wes Holsapple, president and CEO of Jackson's Venture Incubator, said last year that his goal was to serve at least 30 local businesses by the end of the second quarter through its different levels of membership, which allow clients to only lease an office, or use the organization for training, development and networking.

The incubator hosted a private tour April 5 at its new location at the City Centre on Lamar Street, after unexpectedly having to leave its location in the Regions Building. Hertz Investment Group, the owner of the Regions building, had donated space to Venture Incubator since October. The group announced March 25 that the state Personnel Board and a division of the Department of Finance and Administration signed leases for more than 50,000 square feet of space. At the event, several new clients mingle in a small space in the center of its new office. The incubator will host an official open house this summer.

Holsapple, who selects the clients, says the incubator is still growing and hasn't yet taken hold like other cities. But he hopes that his clients' success will create momentum for future business owners. The new clients, who are in the process of moving in, are at various stages in their businesses' growth but still need the support and structure of an incubator.

Emerge Memphis, an incubator in Memphis, Tenn., has been a successful model for helping entrepreneurs meet their goals. Emerge Memphis President Gwin Scott says that incubators must set benchmarks and measure their clients' success to play a prominent role in a city's business growth.

Scott says Emerge Memphis delivered 12,000 consulting hours to its clients last year and reviewed 500 business plans.

"The average company in here grew by 35 percent in revenues last year," he said. "These are metrics that we want to make sure we are continuing to promote. This is time we are spending with companies, and holding them accountable and challenging them to do what they say they are going to do."

Working with the Giants

When California developer Jesse Wright purchased the 34-acre Jackson Square Shopping Center at Terry Road and Interstate 55 last February, the shopping center, which had fallen victim to urban blight, looked like a war zone. The shells of former businesses were filled with trash and the homeless, who took shelter in the space, had started fires to keep warm.

The shopping center's decline started in the 1980s and continued into the 1990s when its anchor store, Zayre's Department Store, closed its doors. When Zayre's closed, Johnson says the other stores "scattered like ants."

"Call it white flight or urban decline, but when taxpayers left the city—white or middle-class citizens—they no longer had interest to come back and keep up with properties," Johnson said.

The shopping strip needed massive renovations, but Wright and property manager Kenneth Johnson were determined to revive it.

Today, the shopping center is hardly recognizable from its former self. The developer installed exterior lights and air conditioning units, and brought the strip mall back to life.

Johnson has big plans for the center. Inside the property's leasing office, Johnson points to a map, which shows that its south building is 90 percent leased. The shopping center now houses Ward 7 City Councilman Tony Yarber's P.H.A.T. Church, a sobriety center, clothing stores and a bingo hall. Johnson recently signed leases for two more clothing stores, a day-care center and a hair salon.

The north building appears desolate at the moment, but Johnson recently signed leases to bring in a blues and jazz lounge, a hair salon and an upscale nightclub—all locally owned.

But Johnson is most excited about plans for an events space and movie theater to move into the 20,000-square-foot space next month. Johnson said that the independent owner, who declined an interview, is renovating the center's former movie theater space to create a dinner theater to show movies and live plays, and provide a venue where bands can perform.

"There is a lot taking place in south Jackson. A few years ago, we weren't a focus. But now I think we have raised enough noise and held the mayor to a standard of focusing on other areas for development besides downtown," Johnson said. "He made that his campaign promise, and he is certainly trying to live up to that."

Johnson has also been steadily working to secure a grocery store in the shopping center to move into the large 40,000-square-foot space that Jitney Jungle previously occupied in the north building. So far, he says, the extent of renovations needed have been a detractor for grocery stores that he has tried to bring in.

As more businesses move into the center, Johnson hopes that the increase of traffic and revenue will attract a larger chain store to serve as an anchor. Eventually, he wants to renovate the strip's blue awnings and brick facades to create an appealing outlet mall, similar in appearance to the Renaissance at Colony Park in Ridgeland. In 2007, Ridgeland approved tax increment financing for developers to build the Renaissance, which is home to several high-end chains such as Anthropologie, J. Crew and Banana Republic.

"If you look at the area now, we don't have population (or) income to support a development like the Renaissance. So we aren't going to see Ann Taylor Loft or Ralph Lauren open stores here. When this area comes back—and I'm not saying 'if,' I'm saying 'when'—our goal is to become an outlet mall," Johnson says.

"Right now, we need tenants that will thrive here and cater to the population—which is low-to-middle income," he adds. "If we can get an anchor store to draw populations, a number of local tenants will thrive as a result."

Johnson says that when it comes to making the decision on what types of stores to lease space to, the strip wants to support local businesses. But in the end, they have to adapt to changes.

"We want to completely tear up this façade, dice larger buildings into small stores, and we have a plan to build apartments on top of the stores," he says. "... We want to create the Renaissance (at Highland Colony Park) of south Jackson. We would want to have a façade that would match them. If these businesses can keep up with this, they can stay."

Johnson added, however, that he wants to replicate the exterior of Ridgeland's Renaissance, and not push small business owners out with high-end stores, even though the rent could increase with the addition of corporate stores.

"It needs to have a local feel and a local vibe to reflect the area," he says. "... I don't want to create too many cookie-cutter stores, because I believe locally owned stores can provide the same services with a smile on their face."

For retail developers, creating options for small-business owners to set up shop can be a challenge. Because of the millions of dollars it takes to complete a development, banks like to see tentative agreements with well-known chain and corporate stores.

"A lot of times, these mega banks want to see corporate chains in contracts because they believe that's a sign of stability," says Jeff Milchen, co-founder and outreach director of the American Independent Business Alliance, based in Boulder, Colo., with affiliates all across the United States. "More and more today, that's less of an indicator, but there isn't a valid reason for that. But that's an issue for developers—there are financiers who want to see big corporate names on the table."

Fondren currently does not have a single corporate anchor store, but its business community is flourishing. In the last month, Salsa Mississippi, a dance studio, has moved to the center of Fondren. A sushi restaurant opened its doors, a new consignment store opened in Duling School, and the Fondren Art Gallery expanded. A new clothing store will soon open in the former Orange Peel space, after the popular consignment store moved to a larger space a few blocks away on Mitchell Avenue.

David Waugh, president of the Fondren Association of Businesses, says his organization supports an anchor store moving into the area, but adds that it's important to find a corporate store that fits into Fondren and won't compete with existing business owners.

"Historically, if you have some of the chain stores on the smaller scale—not big-box stores—they can provide a draw to get people into smaller locally owned stores. We are trying to figure out how that mix works," Waugh says.

For instance, Waugh says, a chain fast-food restaurant like McDonald's would not work because it would compete with Rooster's. But the advantage of a chain is that they bring stability into a business district because a chain can sustain itself through a business' inevitable first-year revenue loss.

"The chains have financing and capital to get through the first few years," he says. "The first year, you won't make any money at all. The second year, you have to pay back what you lost. It's not until the third year that you make a profit."

Milchen echoed Waugh's assessment, adding that if there is a balance, chain stores and small businesses can mutually benefit—but it takes developers, business owners and city leaders to make sure that balance is occurring.

"I think they can live and compete, to some degree, with each other without a problem if there is sufficient consideration given to trying to first fill the needs of what a local business can provide and then looking at other options," Milchen says. "If there are unmet desires in that shopping area, where no local prospect can be identified, it's OK to look at outside companies as a secondary option, not a primary one."

Hard Lessons Learned

During his first few weeks in business, Moore learned some lessons about how difficult it can be to run his own bakery. Because he opened the bakery on a minimal budget, he has to wait for the cash to flow before he could hire more help. Although he had hired a full-time baker, and his wife helped run the cash register, Moore was essentially trying to do all the work himself while the customers were not letting up.

Moore arrives to work at 2 a.m. Wednesday, April 6, to begin baking for the day, and he works nonstop until Thursday at 11 p.m. On Wednesday evening, after making about 60 petit fours for an order due the next morning, he realizes an ingredient has gone bad. He has no choice but to start over on the entire order.

"To make petit fours, you have to bake a cake, slice it and let the icing dry. You can't do it quickly," he says. "It's an hours-and-hours-long process, (and) the people were coming in at 10 a.m. to pick it up."

Moore works a 48-hour shift before he goes home to crash, only to do it all over again. No matter how much he bakes, he can't seem to keep up with his customers' demands.

"I have to work through the night. In the first 15 days of being open, I have pulled four all-nighters," he says. "We keep baking more. I don't keep making the same mistake. But we just keep selling out—the people just go crazy for it. It's a problem, but a good problem to have."

In the past week, Moore has hired two cashiers and two additional bakers. He has plans to hire two part-time cake decorators. While he has always enjoyed baking, he is determined not to get trapped in the kitchen. He wants to be more than a baker; he wants to be a business owner.

Even though the past two weeks have been hard, they have also been some of the most memorable and adrenaline-filled times of Moore's life. He admits he could not have opened without the help of his friends and family, and the support he's gotten from the community has been overwhelming.

"People have said thank you, not just for reopening because they can have cookies, but these people grew up with Campbell's for 50 years, and they don't want to see it gone," he says.

"Now it has a chance."

Related Stories

Shopkeep: Papaw's Crafts

Biz Book Shelf

JFP Business Blog

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus