Tom Sancton has had an interesting career as a journalist. He is a former Time magazine reporter and editor, contributor to Vanity Fair, Fortune, and Newsweek, and author of a bestselling book about the investigation of Princess Diana's death.

But it turns out the most interesting things about him are his family ties and his adolescent jazz apprenticeship in New Orleans with Preservation Hall old-timers, some of whom were contemporaries of Louis Armstrong.

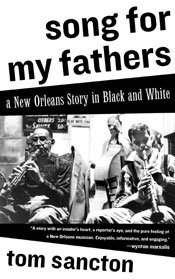

I overlooked Sancton's memoir, "Song for My Fathers: A New Orleans Story in Black and White" (Other Press, 2010, $14.95), when it was published in hardcover four years ago, but I am grateful that its reissue in paperback found its way to my doorstep.

Sancton grew up in racially segregated New Orleans, where his father worked as a reporter for the Item and garnered a reputation as an unrepentant liberal during the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, when going against the grain could get you beaten up or worse. His mother, the daughter of a Mississippi Supreme Court justice and debutante in her native Jackson, was no less interesting, especially for the grace with which she supported her husband and then her son on racial issues. With parents like that, how could Sancton do anything but become the only white teen in New Orleans to play clarinet with the "mens" of Preservation Hall.

Sancton's notoriety as a teen was such that a local television station did a story on him as part of a series named "Terrific Teens." The story was taped at Benjamin Franklin High School, so he figured that when it aired he would be greeted as a star by the other students. "Instead," he reports, "people avoided me in the halls. The gym teacher, Coach O'Neal, took me aside and said, ‘I thought that show was going to feature Franklin. It was all about you and those people at Preservation Hall.' He didn't need to be more explicit. I understood then that ... a young man trying to live in two worlds was considered weird."

If the heart of this book is the New Orleans music scene—not the hit-making superstars who rode about town in limos, but the lowly pioneers of jazz who drank cheap whiskey and made music because it was all that they knew how to do—then the soul of the book is the author's account of his relationship with his father and mother.

The book chronicles the author's complicated family and music relationships in an engaging manner that makes it difficult for the reader to separate the two. The moving death of the author's mother is matched by his determination to repair a broken relationship with his father, due in no small part to his sometimes unflattering portrait of his father in the hardcover edition of this book. In the paperback edition, he writes of his mother's final days and his father's rejection, initially, of his attempt to be the good son.

After his mother's death, his father refused to allow him into his home, so bitter was he over their relationship. Concerned about his health, the author drove by his house on a regular basis and left groceries on the doorstep. Finally, he received a note from his grieving father: "I don't need any more food. But I would appreciate it if you could come over and replace some light bulbs."

It was the opening that he had been waiting for. Later, his father told him: "We're as different as a biological father and son can possibly be ... but we have to find a way to work it out."

I have always had a weakness for coming-of-age books set in the South; however, it was not until I read Sancton's memoir that I realized that such books are flawed as art if race is the engine that drives the story. After all that has been written about growing up in the South, beginning with Mark Twain's fictional adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn (thinly disguised memoir), and continuing to the present-day deluge of memoirs about growing up amid racial hatred, there is absolutely no reason to think that anything has been learned from all those hard-fought experiences, at least not by the population as a whole.

Southerners are not quick learners when it comes to the past. We repackage history and try again in myriad ways to return to the so-called "good old days." Nostalgia is a curse, not a blessing. We've been playing this sad tune since before the Civil War—and it just seems to go on and on and on. It makes you wonder if we will go into the next century and the one after that still dealing with the same unresolved issues.

I'm not optimistic that the South in my lifetime will move far beyond current racial attitudes, which is why I think you might want to overlook that facet of this book and throw yourself into the rich music and the heartfelt father/son reconciliation that elevates this story from a pedestrian "music history" to a higher plane of art for art's sake.

James L. Dickerson's coming-of-age story is presented in bits and pieces in "Devil's Sanctuary: An Eyewitness History of Mississippi Hate Crimes," (Lawrence Hill Books, 2009, $26.95) which he co-authored with Jackson attorney Alex A. Alston Jr.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus