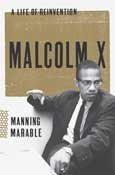

When Columbia University professor Manning Marable passed away April 1, three days before the publication of "Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention" (Viking, 2011, $30), he had already long since written the definitive biography of W.E.B. DuBois and the definitive biography, in documentary format, of Medgar Evers. His biography of Malcolm X, the most exhaustive ever written, completes a trilogy of black civil-rights biographies that has in many ways permanently changed the field of American history in general, and particularly African American studies.

The third volume pre-sents a challenge. To tell the full story of Malcolm X's life without contradiction, Marable was forced to confront and dismantle Malcolm's own account, as presented in "The Autobiography of Malcolm X: as told to Alex Haley" (originally published in 1965).

Unsurprisingly, Marable is devastatingly effective. Where Malcolm claimed he had been unemployed and a violent criminal for several years beginning in 1942, for example, Marable proves that Malcolm had in fact spent the 1942-1944 period as a dishwasher at a popular Harlem jazz bar, and that most of the crimes he claimed to have personally committed during this time never even occurred.

The book is peppered with this sort of data. And by researching correspondence between Alex Haley and Doubleday, Marable is also able to establish that Haley was forced, due to Malcolm's travel schedule and unexpected death, to write the book's climax—describing Malcolm's supposed transformation from an allegedly violent black nationalist into an allegedly nonviolent integrationist—with very little input from Malcolm X himself.

But Marable doesn't call Malcolm X a liar. What he does suggest is that Malcolm—from the beginning of his life until the end—was a man who was willing to sacrifice everything to end the oppression and exploitation of those he loved. It is unsurprising that Malcolm sacrificed the factual details of his life story to the cause when we see that he also sacrificed his personal relationships, his financial stability, his health, his institutional support and, ultimately, his life.

Malcolm X, despite a reputation for arrogance, clearly did not consider himself important; there was nothing he was not willing to sacrifice. He lived and died for black liberation.

Marable indicts the original investigation into Malcolm's death, making an unassailable case that the New York City Police Department intentionally chose to allow Malcolm's assassination rather than to pursue obvious leads. The investigation into Malcolm's death was incomplete, Marable writes, and led to the successful prosecution of at least one innocent man.

Malcolm also "made the conscious decision not to avoid or escape death," Marable points out. He was, in other words, a willing martyr. As long as he stayed abroad, Malcolm was not in danger of assassination; his decision to return to the United States was his march from Gethsemane to Golgotha. He even went so far as to disarm his security personnel—a decision that probably saved their lives, but increased the chances that an attempt on his own life would be successful.

He was ready to die, and he had no interest in taking anybody else with him.

Marable's book reminds us that Malcolm preached anti-Semitism, anti-white ideology, misogyny and homophobia during his years with the Nation of Islam. Haley's account describes a penitent Malcolm who, transformed by his travels and by his disillusionment with Elijah Muhammad, became an integrationist whose views were in alignment with the mainstream Civil Rights Movement. This, Marable argues, is only half-true.

Malcolm did abandon black separatism, but he did not abandon black radicalism. Citing Malcolm's final speeches, Marable argues that he continued to see himself as part of an international Pan-African struggle against colonial oppression, and he continued to see the dismantling of institutional racism—and the establishment of black power structures—as essential to the future of black equality.

Marable makes the persuasive case that Malcolm, at the end of his life, sowed the seeds of Stokely Carmichael's radical and sophisticated concept of Black Power, and still bore little ideological resemblance to more mainstream figures in the movement. What he did have in common with the integrationists was that he had finally come to believe, for perhaps the first time in his life, in the possibility of white redemption.

The author suggests that Malcolm's role as an ambassador to global Islam had, at the time of his death, begun to eclipse his role as a strictly American black leader—leading me to wonder how much different the story of the past 50 years might have been if there had been such a clear point of interaction between the American progressive left and the international Islamic social justice movement.

Ossie Davis eulogized Malcolm as "our shining black prince" because, he said, "a prince is not a king."

Had he survived, Malcolm X might have bridged the gap between U.S. civil-rights activism and global Islamic radicalism—providing avenues for communication and reconciliation that could have undermined international terrorism and saved thousands of lives. He was, as we all inevitably are, interrupted.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus