In the documentary "M is for Mississippi," James "Son" Thomas says: "Daddy always told a joke. He said, ‘There's lots of ways you can have the blues. If you're broke, you got the blues. If you're hungry, you got the blues. If you got a good woman, and she quit you, that ain't nothing but the blues.'"

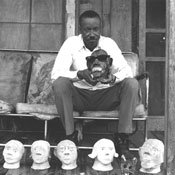

Thomas knew the blues. Born Oct. 14, 1926, in Eden, Miss., Ford never knew his father and was reared by his paternal grandparents. He'd spend time on the banks of the Yazoo River, digging up clay then sculpting it.

"I tried to make a mule, and just kept on trying to make a mule. Finally I could make the mule. Then after that, I started making different things; you know, like birds, rabbits, squirrels. Stuff like that," Thomas said in a 1983 interview with Philip Walker of Bomb Magazine.

The budding sculptor gained notoriety crafting clay skulls. The young boy's grandfather was deathly afraid of ghosts, so to scare his pops, Thomas created a skull and placed it in a darkened corner he knew his grandfather would pass by.

As he got older, Thomas earned money working on a plantation and as a gravedigger. During the day, he harvested and dug, and at night, while his grandfather drank moonshine and tossed dice, he sculpted.

In 1981, curators featured many of Thomas' handcrafted skulls in "Exhibit of Southern Folk Art" at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

A few days before he left to attend the exhibit opening, his girlfriend shot him.

"My old lady had shot me with a .22," he said. "It wasn't an argument. She just shot me. I got out of the hospital, and I had four or five days before I could leave."

Thomas pressed on and met then-first lady Nancy Reagan. "(Mrs. Reagan) had a lady in the front of her—her guard, I imagine—and (the guard) told me she was coming through," he said. " ... and when she comes by, she throwed her arms around me. When she put her arms around me, she put a hand right where they cut that bullet out."

But, of course, visual art wasn't Thomas' real claim to fame. It was music. His curiosity began when he'd sit and listen to his uncle, Joe Cooper, sing and play the blues, or the family would sit around listening to records by "Big Boy" Crudup and Skip James. As Thomas' interest grew, Uncle Joe taught his nephew a few chords and charged him to practice. When his uncle would leave for work, he'd sneak in to practice on his uncle's prized guitar.

Working in the cottonfields, Thomas earned enough money to buy his own guitar from a Sears & Roebuck catalog. The musician began to frequent Yazoo City juke joints as he improved his skills, and there he met artists like Rice Miller and Elmore James. The two later befriended Son and encouraged the "apprentice" to play along with them.

Thomas' mentoring relationship with the bluesmen built confidence, and he began work on his own set of songs, like "Catfish Blues," "Ludella" and "Cairo Blues." These tracks were synonymous with his performances.

Slowly, his name became known, but before he made enough money with music to pay his bills, Thomas continued working as a gravedigger and later took on a job at a furniture store.

When researcher William Ferris "discovered" Thomas in Leland, he made the "Catfish Blues" singer the focus of several academic papers and magazine features. Thomas was suddenly an attraction at blues festivals locally, regionally and overseas, billed as one of the Delta's last living originals. He constantly battled with his poor health, however. Back pains and emphysema bothered him, and in 1991, he had surgery for a brain tumor.

Despite his fragile state, Son continued to perform until May 1993 when, at age 66, he suffered a stroke and remained in the hospital for a month before he passed away. Chiseled on the headstone at Thomas' Leland grave are the words from one of his songs, "Beefsteak": "Give me beefsteak when I'm hungry / Whiskey when I'm dry / Pretty women when I'm livin' / Heaven when I die."

Beefsteak

James "Son" Thomas' eponymous album is widely acclaimed by critics and blues fans alike. From "Mama Don't ‘Low No Guitar Playin' ‘Round Here" to "Hoochie Coochie Man/Try Me Next Time" and track number three, "Beefsteak Blues," baptize yourself in the musician's work with "Beefsteak Blues." It's the best place to start.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus