You've probably never heard of Daniel Lanois, but you've certainly heard his work. He has quite an impressive resumé: producer of CDs recorded by Bob Dylan, the Neville Brothers, Emmylou Harris, Willie Nelson, U2 and Peter Gabriel, to name a few.

Lanois is not the sort of producer who strives for No. 1 hits, not in the vein of a Chips Moman or a Quincy Jones; instead, he goes for music that achieves its greatness by virtue of its accumulative value. In other words, hit singles are not his forte. Memorable albums and movie soundtracks are more his style.

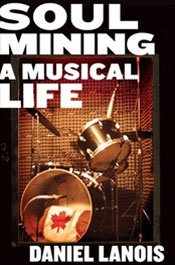

In "Soul Mining: A Musical Life" (Faber and Faber, 2010, $26), Lanois tells the story of his life, a memoir he co-authored with Keisha Kalfin, a novice writer who works on his staff. The book has all the flaws you would expect from one penned by non-writers—self-absorption being the most notable—but it also possesses an engaging energy that makes it worthwhile, fascinating in that way that a cat on a hot tin roof is fascinating.

Those who like to analyze American musical history and current trends have always been fascinated by the dominance of two groups that have been key to the success of American music: southerners (particularly from Mississippi, Louisiana and Tennessee) and Canadians. Without those two groups, there would be no original American music.

I don't have to tell you the names of southerners who have influenced American music, but I should drop a few names of Canadians who have played critical roles in the development of music: Celine Dion, Neil Young, Shania Twain, Alanis Morissette, Joni Mitchell, Anne Murray, Bryan Adams, "Late Night with David Letterman" band leader Paul Shaffer, and the list goes on.

Lanois is French Canadian, a native of Quebec, where he grew up in a poor family. He saw music as his way out of poverty. While still very young, he performed on the Canadian show band circuit, where he sometimes worked with a female impersonator named Ricky Day and a stripper who used the name Delightful Delilah. With a start like that, how could he not gravitate first to California and then to New Orleans?

One of my favorite chapters is the one about the Oscar-winning movie "Sling Blade," the Billy Bob Thornton masterpiece that was enhanced considerably by the soundtrack Lanois wrote and produced for it. As you would expect with a movie like that, the soundtrack did not have a traditional birthing. Think "Rosemary's Baby."

For starters, he rented an old Mexican movie theater in Oxnard, Calif., named the Teatro. What better place to produce a movie soundtrack than in an actual movie theater?

He moved in with his toothbrush and recording equipment and set up shop, beginning with the purchase of war-surplus parachutes, which he hung from the ceiling to help deaden the high-frequency renegades that sometimes ricochet about a studio. Then he hired a Canadian orchestra and installed them in a seedy motel next door so that they could be available 24 hours a day.

The mechanics of setting up a recording studio are interesting enough, but nothing compared to the experience of working with Thornton. Wrote Lanois: "Billy would roll down with a jar of white lightning, some kind of hard-hitting stuff that a friend of his had brought back from Arkansas. Billy was having migraines then, and there were times when I didn't know if he was in the Teatro or not. He would pass out upstairs in the projector booth, and then wake up half a day later and be standing there like a ghost."

If you know anything about movies, you know they are made without music. Composers watch the film and then compose soundtracks for individual scenes. In the case of "Sling Blade," Thornton brought a VHS player in so the orchestra could play music while watching the tape. The results were spectacular. The soundtrack is every bit as haunting as the images viewed on screen.

Another interesting chapter is the one about recording Bob Dylan's "Time Out of Mind" CD, one of the best efforts the legendary performer has done in years. Considerable give-and-take characterized the sessions, but the results were not always satisfactory to both parties. Lanois wanted Dylan to "align" himself with hip-hop greats and "build and maximize" the groove in his music, a suggestion Dylan resisted. They were awarded two Grammies for the album, but it never became a hit, and Lanois seems to blame Dylan for not taking his advice. Dylan does what Dylan does.

Sometimes the mind-numbing detail associated with the "Time Out of Mind" sessions and others is more than the reader can appreciate. I recommend reading the book, not for the technical tidbits (unless you are a professional musician) but for the richness of a life lived from moment to moment, with the unexpected always a possibility:

Bob [Dylan] called me in the middle of the night . . .

I said, "Bob, what time is it?"

He said, "It's dark out."

I said, "Where are you?"

He said, "Drifting."

James L. Dickerson is the author of two award-winning music books, "Goin' Back to Memphis: A Century of Blues, Rock ‘n' Roll, and Glorious Soul" and "Mojo Triangle: Birthplace of Country, Blues, Jazz and Rock ‘n' Roll."

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.