Hank Thomas walked up the steps of the Greyhound bus on a sunny day May 4, 1961. As he calmly surveyed its drab, blue-gray interior, the lanky 19-year-old black student from Howard University had no idea that in about two weeks he would come dangerously close to meeting his maker on its floor.

He wasn't prepared for the violence, Thomas says now. "I'm pretty sure there were some folks who had been in some civil-rights activities before, and I know there were those, and they may have (been prepared)," he says.

The Congress of Racial Equality, known as CORE, organized the Freedom Rides to test the recent Supreme Court decision, Boynton v. Virginia. The decision made racial segregation in interstate bus stations, restaurants, bathrooms and buses illegal. CORE's plan was to make sure the decision was being enforced by riding buses through Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and end with a rally in New Orleans.

Seven blacks and six whites made up the group. The black Riders would sit in the front, and the white Riders in the back. One interracial pair sat together. The exact formation would be determined the night before each ride in daily meetings. A couple of the Riders would sit in a segregated manner, so that they could bail out the other Riders if they were arrested. They would take two buses, a Greyhound and a Trailways.

The group had recently completed a four-day non-violence training in Washington, D.C., where they learned how to passively protect themselves and deal with potential physical altercations, of which there would be many.

After leaving Washington, D.C., on May 4, they made their first stop in Richmond, Va. Some white onlookers jeered at the Riders, but there was no violence. This stop was one of the few that the Riders would later remember as uneventful.

They stopped in six places before arriving in Charlotte, N.C. The black Riders walked into the white waiting room and met with no resistance. The Riders milled around the station, and just when it seemed that this stop would be as uneventful as the last, Charles Person, a muscular, taciturn Rider, decided that he needed to get his shoes shined.

"You know you're sitting on a bus, you're getting on and off the bus, and your shoes get scuffed up a lot," Person says.

"As I was exiting the restroom, I saw the shoeshine man there. I asked him, you know, 'Can I get a shoeshine'? He said, well, he couldn't shine my shoes, and if I persisted I would be arrested."

Getting a shoeshine wasn't one of the planned tests, so Person didn't persist, but another Rider, Joe Perkins, decided that he would demand a shoeshine. Charlotte police officers arrested him when he persisted.

With the exception of this setback, and some unpleasant expressions from white onlookers, the Riders experienced no serious problems at the Charlotte bus station.

Things would get physical soon enough.

N*gger, Get Out of This Car

When the bus stopped in Winnsboro, S.C., John Lewis and Albert Bigelow were the first black Riders to get off the bus and walk into the white waiting room, where the Riders' first brush with violence took place.

"They were accosted by several white toughs," Person recalls. "They were punched, and they were roughed up pretty good. Before it got too bad, the local authorities came in and stopped it."

Shortly after the authorities gained control of the situation, Hank Thomas entered the terminal and sat down at a whites-only lunch counter, where local police arrested him. He was then escorted to their patrol car and taken downtown.

After pulling into the parking lot, the two police officers led the handcuffed Thomas into the station and did something that, in hindsight, he realizes was quite strange: They took him directly to a jail cell without booking him.

"As I remember back at the time, the fact that they didn't fingerprint me, I thought that was weird," Thomas says.

They didn't take a mug shot, fingerprints, or ask for any personal information. To this day, the Winnsboro Police Department has no record that Hank Thomas ever entered their station.

That night, the police opened up his cell and said that they were going to take him for a ride.

"Where am I going?" Thomas asked.

"You want to leave? We're going to take you to the bus station so you can leave," one of the officers replied. The officers then put Thomas in the back of the patrol car again and headed back toward the bus station in the dark of the night.

As the patrol car passed under the dim street lamps, Thomas could see the silhouette of the station in the distance and knew something was wrong.

"I could see it; all the lights in the station were out. A large crowd of white men were there around the bus station. It looked as though they'd been having a good time, been drinking, and I could see a few sticks and everything they had in their hands, and as the police car got perhaps within a half a block of the bus station, they stopped to let me out."

"Well, there's the bus station," the officer who was driving said after stopping the car. "You can go."

Aware of the danger that lurked outside the car, Thomas said, "Well, it looks like the bus station is closed. When will the next bus come?"

The officers muttered something about having no idea about the bus schedule.

"I can't get out here. It looks pretty dangerous," Thomas responded.

"You wanted to go. You can go," one of the officers said, becoming impatient.

Thomas, determined to stay in the safety of the car, said that he was not going to get out. The police officer in the passenger's seat then turned around, and while Thomas could barely make out his face in the darkness, he could see the glint of his pistol as the officer said, "N*gger, get out of this car."

"If I didn't get out of the car, I figured he was going to shoot me, so I did, and as soon as I got out of the car, the police took off," he remembers.

And so on this cloudless night in May, Hank Thomas found himself on a dark street with an angry white mob only a stone's throw away.

"I had to make a quick decision," Thomas says of that night. "Of course the crowd started running toward me, and I was a pretty athletic fellow at that particular time. You know, I knew I could probably outrun them. So I started to run."

Heart racing, Thomas took off sprinting in the other direction. He ran down one street and then down another, heading nowhere in particular.

As he was sprinting down this second street, Thomas came across a bit of luck. A black man pulled up beside him in a car and said, "Son, get in and get down on the floor." Thomas, happy to oblige, whipped open the door and immediately got down on the floorboard.

"I was expecting to hear gunshots through the rear window at any minute," he remembers.

From that street in Winnsboro, the man drove him to Benedict College in Columbia, S.C., which is where the Riders' next planned stop was. The Riders were already on their way to Atlanta, however, because they had only made a brief stop in Columbia. Thomas then took a bus by himself from Columbia to Sumter, N.C., to catch up with them.

Three stops later in Atlanta, the Riders met with Martin Luther King Jr. and his father, Martin Luther King Sr., at their church, Ebenezer Baptist. The father and son, along with their staff, warned the Riders that Alabama and Mississippi were different than the other states.

"We were told that (Anniston, Ala.,) was a hotbed of Klan activity, and so it was not going to be a pleasant stop. We were aware of that," Thomas says.

'I'm Going to Die'

The Greyhound bus left an hour ahead of the Trailways, and the Riders on the first bus knew something was up soon after they crossed the Alabama state line. About an hour away from Anniston, another bus came into view, and its driver flagged down the driver of their bus.

"They both got off their respective buses and talked for a few minutes, and then our bus driver (who was white) got back on, and he looked at us," Thomas says.

"I remember him having somewhat of a smirking smile on his face. Nobody said anything, and the bus was very, very quiet for the rest of the way."

After another hour of riding, the Anniston city limits sign came into view. The Riders, peering outside the bus as they drove into the city, realized that the downtown streets were completely empty, another ominous sign.

As they turned down the road that led to the bus station, they could see a mob of white men, many of them Klansmen, surrounding the terminal.

"As the bus pulled into the station, they all surrounded the bus, yelling and screaming," Thomas recalls. "I remember the bus driver getting off the bus and saying, 'Look fellas, all I did was drive y'all here.'"

The driver then got off the bus, but before he did, he locked the door from the inside. The white throng then started beating on the bus, but they couldn't get inside.

"I don't know how long it was," Thomas says. "It probably was not near as long as it seemed."

After this went on for several minutes, a different bus driver approached the locked door; he too found that he couldn't get inside, so he went around to the driver's side and unlocked it with a key.

"As he tried to pull out, there were men in front of the bus. Several of them sat down in front of the bus, and as he lurched towards them I guess that's when they moved to let the bus come past them," Thomas says.

The men moved, and the bus was out of the station area, but their problems were not over.

"Three or four pick-up trucks were in front of the bus and would not let it pass, and a long caravan of cars were behind the bus," Thomas says.

The bus was sandwiched between the two groups of vehicles. When the driver tried to speed up and pass the trucks in front, the trucks would simply speed up, too. The cars behind the bus wouldn't allow it to slow down. As the bus rode along, the Riders realized that it was slowing down.

They would later find out that the tires were slashed, most likely by the men who had been squatting in front of the bus back at the terminal.

"The bus driver had to pull the bus over to the shoulder of the road," Thomas recalls. "Strangely convenient, because at the point that the bus pulled over, a crowd of people had gathered; they had just come from church."

This crowd also surrounded the bus and began beating it with sticks and rocks and bats.

"I remember I was trying to look straight ahead and not look at the mob," Thomas says. "One guy with, (what) looked like a heavy rock, threw it up against the window, and I was sitting next to the window, and the window cracked, but it didn't shatter, so the rock didn't come through."

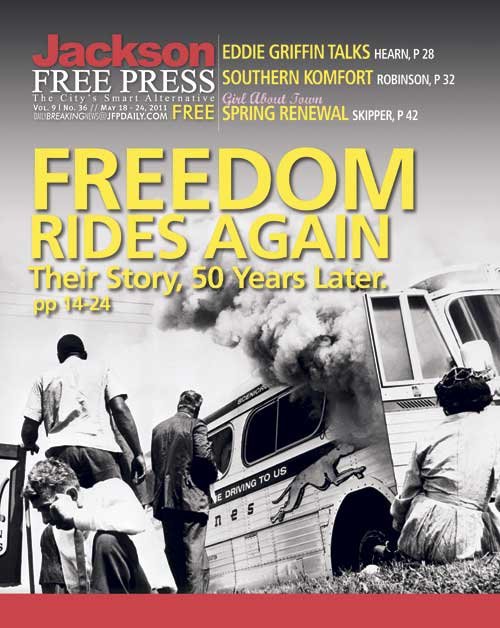

Then, one of the rioters threw a small Thermite bomb on board through a broken window, which caused the bus to catch on fire.

"I remember Albert Bigelow (another Rider), who's a retired Naval captain. ... He said 'Get down on the floor, and put your nose down against the floor because that's where you will find the oxygen,'" Thomas says. "Well that only lasted for a few seconds. And I remember thinking, 'I'm going to die. And if I get off this bus, the crowd outside's going to beat me to death. And if I stay here, and I breathe this stuff, maybe it'll put me to sleep, and that's how I'll die.'"

After lying on the floor for a few more moments, Thomas found that he couldn't just lie there.

"When the smoke gets in your lungs, involuntary reactions take over, you fight for air. ... That's when I got up, and I thought, 'As large as I am, I can slam my shoulder against the door and get the door open,'" Thomas says.

Thomas slammed his shoulder against the door once, but several men had wedged themselves against the door. He vividly remembers one of the men shouting, "Let's burn them n*ggers alive!"

But then something unexpected happened: the fuel tank exploded. The crowd outside started to run away from the bus, allowing the Riders to get off. But after a minute or so, several white men started in on them again. One of them, Thomas remembers, hit him with a baseball bat.

Thomas then spotted a state trooper who was just standing around, not doing anything.

"I got behind him, and in the process of doing that I put my hands on him and, you know, pushed him in front of me," Thomas recalls.

Thomas was terrified to see the Trooper pull out his gun, but instead of pointing it at him, the cop fired into the air and said, "OK, OK. You've had your fun."

The crowd calmed down.

Soon, an ambulance showed up; but it was a "white" ambulance, and its drivers, according to Jim Crow laws, refused to take blacks to a hospital. The white Riders were not going to leave the black members of their group without medical care, so they, in turn, refused to board the white ambulance.

One of the white Riders, Ed Blankenheim, offered his oxygen mask to Hank Thomas in front of a white firefighter.

"He let me breathe that oxygen, and the white fireman was beside himself. ... This black guy is breathing the oxygen, and that was just not supposed to happen," Thomas remembers.

After careful consideration, the trooper decided to order the ambulance drivers to take all the Riders to the hospital. Once the Riders got there, however, the mob besieged the hospital. The hospital featured separate emergency rooms for whites and blacks. The white emergency room refused to treat the blacks, so the white Riders refused to be treated.

About this time, an official working under U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy called Alabama Gov. John Patterson to explain the gravity of the situation, Thomas says, and the Riders received treatment. Due to the smoke inhalation and the beatings, however, these Riders were unable to continue on.

"None of us were in any physical shape to continue, so CORE decided to suspend the Freedom Rides, not because they were afraid of what was going to happen to us; we just physically were not able to go on," Thomas says.

Thomas flew back to his home in New York. The rest of the Riders went their separate ways, for the time being.

'They were beating us pretty badly'

While the Greyhound was on the outskirts of Anniston, the Trailways bus was having problems of its own. It had taken a more northerly route than its Greyhound counterpart and took nearly an hour longer to reach Anniston. When the Trailways bus reached Anniston, the bus station was empty.

"Some local people were standing around, milling around, and they were discussing that the other bus had been burned to the ground," Charles Person remembers.

A group of locals who were waiting to get on the bus told the Riders that they weren't going anywhere until the blacks got in the back of the bus. The black Riders on the bus—Charles Person, Herman Harris, Isaac Reynolds and Ivor Moore—refused.

"And then about eight young white guys got on the bus," Person says. "They began to throw punches and so forth, and they were beating us pretty badly, and then two white Riders came from the back, James Peck, journalist and author of "Freedom Ride," and Dr. Walter Bergman."

When the two white Riders came to help, the group shifted their fury to them. "James was just knocked back over, head over heels, and Bergman was stomped, and they finally just stacked us all in the back of the bus. They physically threw us in the back of the bus," Person remembers.

They forced the blacks to the back of the bus and then forced the white Riders into the back as well. "Let the n*gger lovers stay in the back with their n*gger friends," Person remembers one of them saying.

'Just take me somewhere.'

On Mother's Day, May 14, the Riders rode into Birmingham. The ride was tense and quiet, the silence only broken by the occasional taunt from the front, punctuated with the word "n*gger."

It was mid-afternoon when they arrived at the bus station. Charles Person and James Peck were the first of the Riders to step off the bus and onto the asphalt. When they entered the terminal, they walked into what amounted to a Ku Klux Klan meeting.

"The walls were lined with men, most wearing work clothes, khakis and stuff like that. And then, as we got near the center of the waiting room, they all started coming towards us," Person says.

The mob descended on the two Riders, hitting them with pipes, sticks and fists. Peck was forced down to the floor. The next time Charles Person would see him, his face was a bloody pulp.

The Riders later found out that Bull Connor, the Birmingham police commissioner, had given the mob 15 minutes to do whatever they wanted to the Riders. Connor's explanation for his men's absence? They were home with their mothers for Mother's Day.

After this went on for several minutes, photographer Thomas Langston of the Birmingham Post Herald, snapped a picture of several white men beating Person. As the flash went off, the men looked up at the photographer and then began to attack him, leaving Person alone.

"And that's how I was able to escape, because I didn't run or anything. I just walked away," Person says.

Person walked out into the street, and spotted several municipal buses passing by. Bleeding, he flagged one of them down and told the driver, "Just take me somewhere." The driver said that Person would be able to find help across the railroad tracks on the black side of town.

The driver dropped Person off by a telephone booth, where he called Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. The preacher sent someone to pick up Person and get him medical treatment, but the three black physicians in the Birmingham area all refused out of fear.

That evening, all the Riders who had made it to Birmingham met at Shuttlesworth's church. The group discussed the day's events and their next stop: Montgomery. The Riders discovered, however, that no drivers were willing to take the group due to the previous day's violence and the Alabama governor's refusal to provide police escorts. They decided to fly directly from Birmingham to Montgomery.

At the airport, "There were a lot of people ... a lot of unfriendly people," Person says. But there was no violence.

After boarding the plane to Montgomery, the pilot announced a bomb threat, so everyone had to get off. Fearful that they might not get out alive, the Riders decided to fly directly to New Orleans, instead. After a bomb threat to the second plane, the group finally made it out of Alabama.

'Breach of Peace'

The violence the two groups of Riders met in Alabama kept one group from making it past Anniston and the other group from making it past Birmingham. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, led by Diane Nash, didn't want to the Ride to end on such a dismal note. SNCC recruited new Riders from Tennessee State University and Fisk University to pick up where the first Riders left off.

Hank Thomas was in New York at the time, but when he heard that other Riders were continuing the movement, he decided he had to join them. John Lewis, another original Freedom Rider, also decided to make the trip.

Under pressure from the Kennedy administration, Gov. John Patterson provided a convoy of National Guardsmen, armed with fixed bayonets, for the bus trip from Birmingham to Montgomery, Ala., May 24, 1961. The guardsmen escorted the bus to the Mississippi state line, where the Riders were handed off to Mississippi National Guard and the state police. All of this protection ensured that the Ride from Birmingham to Montgomery to Jackson was uneventful. Their stop at the Jackson bus terminal was also uneventful, at least when compared to the other Riders' stops.

"I don't remember a large crowd of people at the (Jackson,) Mississippi bus station, (but) as soon we entered the bus station, we were arrested. And they had the paddy wagons and everything all lined up, so Mississippi was somewhat determined that they weren't going to repeat what happened in Alabama," Thomas says.

After he was arrested, Thomas was brought before Jackson Municipal Judge James Spencer and asked how he pled to his charge of "breach of peace." Before he could answer, Spencer interrupted him, saying, "Don't waste my time. You're guilty."

"That was my taste of Mississippi justice," Thomas says.

While Thomas and the other Riders met no violence in Jackson's bus station, the city's police station would not be so kind.

According to the Jim Crow social etiquette of the day, any black man, woman or child was supposed to answer a white person with "yes, sir" or "no, sir." Determined to avoid this practice, Freedom Riders were taught to carefully word answers.

"If they asked me, 'Is your name Hank Thomas?' I wouldn't say yes or no, I'd say 'My name is Hank Thomas.' 'Did you come from St. Augustine, Fla.?' 'I came from St. Augustine, Fla.'"

When Thomas was booked at the Jackson police station, the desk sergeant asked him if he had any other information that he wanted to provide.

"No," Thomas replied.

"That's when they descended on me," he says. The officers punched Thomas but were careful not to draw any blood.

When they were through, Thomas got up and asked, "What was the question again?"

"Do you have anything else to say?" one of the officers responded.

Determined not to answer using "sir," he returned to the Riders' protocol. "I don't have anything else to say," he replied.

One of the officers then approached Thomas and accused him of "being smart," but the sergeant waved him off.

Thomas spent a week in the Hinds County jail before being transported to the State Penitentiary at Parchman. During his 35 days at Parchman, Thomas was put in solitary confinement twice.

Civil Disobedience

The Freedom Riders sought to test a Supreme Court decision that they knew was not being enforced. The Freedom Ride inspired many blacks living in the rural South to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement at the grass roots level. Their method of non-violent resistance, as advocated by Martin Luther King Jr., would serve as a blueprint for subsequent civil rights work.

When asked what impact the Rides had on him, Thomas says, "They renewed my determination. They made me more determined than ever to fight for equal rights in this country."

The Rides also gave him a new perspective and optimism to rely on when faced with life's obstacles.

"Whenever I had a setback, I said, 'well, I survived Anniston, I survived Jackson, I survived Parchman, and I can come through this as well,'" he says.

Former editorial intern Dylan Watson, aka "the Instigator," is from Indianola. He will be a junior at Millsaps College in the fall, where he studies political science and philosophy.

Where are they now?

Charles Person — The youngest of the original 13 Freedom Riders, Person was 18 when he boarded the bus in Washington, D.C., and a freshman at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. After serving 20 years in the U.S. Marine Corps, Persons taught in Atlanta's public schools until his retirement. He still lives in Atlanta.

John Lewis – born Feb. 21, 1940, was 21 during the Ride. He was elected to represent Georgia in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1980 and still holds this position.

Hank Thomas – Born Aug. 29, 1941, in Jacksonville, Fla., Thomas served in Vietnam in 1965 and 1966. He now lives in Stone Mountain, Ga., and is the owner of four Marriot hotels and two McDonald's.

Also, if you missed the broadcast of the Freedom Riders documentary that aired on PBS, you're in luck. Click over to PBS's video page and view. And while you're there, please be sure to donate.

Related Stories

Jeanne Luckett

[Editor's Note] Strenuous Liberty

Recreating the Rides

'It Won't Be Long'

Common Struggle

Freedom's Main Line

'Jail Not Bail'

Freedom Riders 50TH ANNIVERSARY Events

"An Evening with the Freedom Riders"

May 19, 9 p.m., at Mississippi Public Broadcasting (broadcast channel 29, Comcast channel 7). The broadcast is of a November 2010 panel discussion with Freedom Riders at the Alamo Theater. Visit http://www.mpbonline.org/freedomriders.

Day of Repentance for Slavery and Reconciliation

May 21, 2 p.m., at St. Andrew's Episcopal Cathedral (305 E. Capitol St.). The Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi sponsors the event. Visit http://www.ms50thfreedomridersreunion.org.

Return of the Freedom Riders: 50th Anniversary Reunion

May 22-26. More than 100 Freedom Riders and their families reunite and tell stories about the struggle to end segregation in American interstate travel in 1961. Visit ms50thfreedomridersreunion.org for a detailed schedule. Register by May 18 for advance tickets; limited seating. $175, $100 Freedom Riders, $75 students, $70 one day May 23-26; call 601-979-1517.

Free public events include:

• May 22, 4 p.m., Opening Public Reception and Program at Jackson Marriott (200 E. Amite St.)

• May 23, 10 a.m., Interfaith Memorial Service at Tougaloo College, Woodworth Chapel (500 W. County Line Road, Tougaloo)

• May 24: Freedom Trail Marker Dedication at Greyhound Bus Station (219 N. Lamar St.) at 11 a.m., the All People's Program honoring the Freedom Riders at the original Trailways Bus Station (outside Jackson Convention Complex, 105 E. Pascagoula St.), and the All People's Public Reception, Exhibit and Book Fair at the Jackson Convention Complex at 3 p.m.

• May 26: "The Parchman Hour" plays at Jackson State University, Rose E. McCoy Auditorium (1400 John R. Lynch St.).

Ticketed events include:

• May 23, 11:45 a.m.: Intergenerational Picnic at Tougaloo College, $20.

• May 24, 7:30 p.m.: Freedom Rider Legacy Banquet at Jackson Convention Complex with music by Dorothy Moore, $40.

• May 26, 12:30 p.m.: Freedom Rider Praise Luncheon at Jackson Marriott with guest speaker Dr. Calvin O. Butts, $30. Registration includes all events plus meals, visits to historic sites in the Delta, panel discussions and forums, a youth leadership summit, tours of Jackson civil rights sites and the Freedom Trail Marker dedication at the Medgar Evers Home Museum (2332 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive).

"Freedom's Sisters"

May 25-July 30, at Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center (528 Bloom St.). The interactive exhibition from the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service displays the moving journeys of 20 African American women who changed history and became heroes. The May 23 opening reception is at 6:30 p.m. Hours are 9 a.m.-5 p.m. weekdays and 10 a.m.-1 p.m. Saturdays. $4.50, $3 seniors, $1.50 children under 18; call 601-960-1457.

Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Freedom Riders

Showing through until June 12, at Mississippi Museum of Art (380 S. Lamar St.). The exhibition shares journalist and photographer Eric Etheridge's project of the same name, displaying 328 mug shots alongside 15 contemporary portraits of Freedom Riders. Free; call 601-960-1515.

"The Freedom Rides: Journey for Change"

Showing through until Oct. 31, at William F. Winter Archives and History Building (200 North St.). The exhibit examines the arrival of the Freedom Riders in Jackson, their incarceration at the State Penitentiary at Parchman, and the impact the event had on the civil rights movement. Hours are 8 a.m.–5 p.m. weekdays and 8 a.m.–1 p.m. Saturdays. Free; call 601-576-6850.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.