“Poverty in the Midst of Plenty is a paradox that must not go unchallenged in this country.”

— John F. Kennedy

On April 10, 1963, President John F. Kennedy wrote a letter about the poor to then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. He expressed concern that in this, one of the richest of nations, one-sixth of Americans lived in abject poverty: “below minimal levels of health, housing, food and education—in the slums of cities, in migratory labor camps, in economically depressed areas, on Indian reservations.”

When Kennedy wrote that letter, the United States was a very unequal nation, with wealth and power concentrated in the hands of white Americans with people of color living under Jim Crow laws; dying for the right to vote or walk down the same sidewalks; being redlined out of home, business and car loans; and fighting not to be denied a decent education, wage or opportunity for a good job.

In other words, wealth inequality was rampant, and many people didn’t have bootstraps to pull themselves up by.

It was also true for a large swath of white America, especially in the Deep South. It’s hard to believe today, but Mississippi was one of the richest states in the nation before the Civil War. But it was due to the free labor of slaves and, thus, the poverty of slaves didn’t count to the people in power.

But the devastation of the war, then Reconstruction, and later sharecropping and tenant farming trapped poor whites in cycles of poverty as well as African Americans and other non-whites. So did emerging industry in the U.S., which for years was under-regulated and paid extremely low wages to all races with minimal safety regulations in place.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia reports that poor white southerners bore much hostility from upper-class whites in the decades following Reconstruction, with epithets like “cracker,” “hillbilly,” “clay eater,” “peckerwood,” “poor white trash” and “redneck” entering the lexicon. The image was perpetuated in popular media, helping create conditions that made it difficult for poor whites, as well as poor non-whites, to escape poverty. Powerful, rich people used fear of “the other” to keep the groups divided, even as they shared many economic interests and challenges.

Share of 100 Poorest Counties

No. 1. Texas 17

No. 2. Kentucky 16

No. 3. Mississippi 14*

No. 4. South Dakota 10

No. 5. Louisiana 5

No. 6. Alabama 4

No. 6. Georgia 4

No. 6. New Mexico 4

No. 6. Montana 4

*Poorest Mississippi Counties:

No. 17: Jefferson County

No. 36: Issaquena County

No. 41: Holmes County

No. 46: Tallahatchie County

No. 51: Quitman County

No. 52: Wilkinson County

No. 56: Humphreys County

No. 67: Claiborne County

No. 72: Sunflower County

No. 73: Sharkey County

No. 92: Greene County

No. 95: Jefferson County

No. 96: Tunica County

No. 98: Kemper County

All of these conditions made it difficult for the poor in America, and especially in the South, to believe in their abilities to overcome poverty and to access the resources they needed to change their conditions. Feeding a hungry person is one thing, but feeding them and helping them develop bootstraps to lift themselves out of poverty is a larger challenge that requires will and focus.

Sadly, many of those facts are still true today. Mississippi has never recovered from the devastation of post-Civil War economic conditions and prejudice against the poor and has remained on the bottom of the American barrel for many decades, even as the richest Mississippians have followed the lead of the wealthiest Americans in increasing their share of the pie.

Meantime, problems created by poverty (which are often the same cyclical problems that lead to it) spill over into the entire society in the form of crime, poor health, decreased worker productivity and increased costs of basic needs that deplete funds that could be spent on more innovative purposes than straight-up charity.

Poverty becomes the unaddressed elephant in the room that ruins the party for everyone. Many Americans feel helpless about it, so they don’t talk about it. Others don’t seem to care that they have so much while their neighbor has so little—and, yet, still end up paying the high costs of poverty. They often excuse inaction, or support of policies that increase poverty, by blaming black families for doing too little—despite the fact that more white children in America live in poverty than any other group. It is also a fact that higher percentages of people of color live in poverty.

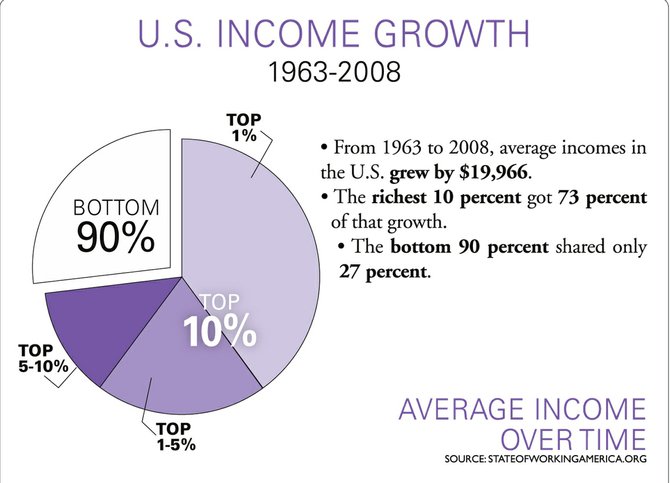

Both realities are bad, whether hard numbers or percentages: Our nation is mired in practices and attitudes that perpetuate the cycle of poverty, even as they increase the wealth of the top 10 percent.

There is a better way. But before we can seriously tackle the poverty crisis in America, we need to understand it. We need to train ourselves to see its causes (without defensiveness), understand its effects and then take actions to reverse both. The good news is that individual people do not have to tackle the entire effect, and it’s not a matter of throwing money at the poor.

Poverty’s pieces are like a jigsaw puzzle. We can choose one piece to focus our efforts. If each of us does that, we can start decreasing poverty in America by systemically helping and empowering people to lift themselves out of it.

The question is: Are we willing?

The U.S. Poverty Line

In 2012, the U.S. poverty level was $23,050 total yearly income for a family of four. Most Americans (58.5%) will spend at least one year below the poverty line between ages 25 and 75.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus