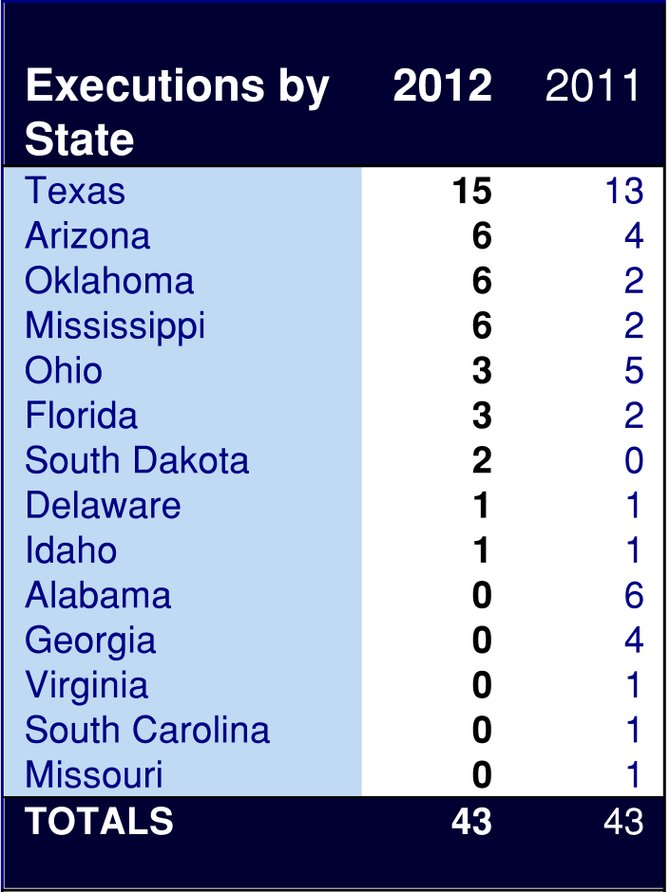

Mississippi rises toward the top in the number of people executed in 2012. Photo by File Photo/Jackson Free Press

Mississippi rises toward the top in the number of people executed in 2012. There, the Magnolia State is tied for the No. 2 spot with Arizona and Oklahoma with six executions each. Texas tops the list by putting 15 of its death-row inmates to death last year.

But even with six states seeing a slight increase in executions last year, death-penalty opponents will find plenty to cheer about in "The Death Penalty in 2012: Year End Report" from the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center.

First, Connecticut became the fifth U.S. state in as many years to abolish the death penalty as punishment, joining New Jersey, New York, New Mexico and Illinois. In all, 29 states no longer include the death penalty among punishments or have not executed a prisoner in the past five years; 17 states have abolished it entirely.

Second, only nine states out of 50 carried out executions last year, down from 13 in 2011. Three of those--Ohio, Delaware and Idaho--saw either a reduction or no increase in deaths. The application of the death penalty has also decreased. "Last year, there were fewer than 100 death sentences, for the first time since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976," the report states. "This year, the number remained well below 100."

The death penalty is an anachronism in the justice system. Seventy-nine percent of all U.S. executions were in only four states. Worldwide, 97 countries have abolished the practice by law, and another 36 haven't executed anyone in the past 10 years, leaving 57 nations that still execute criminals on a regular basis. On Thursday, 111 nations voted for a moratorium on the death penalty at the United Nations; the U.S. voted against the measure.

The reason most cited for keeping the death penalty, that it lowers crime, has been discredited. Stacks of research show that the potential of facing the death penalty has no discernible affect on those committing capital crimes. To the contrary, those on death row are likely to have severe mental or drug problems. "People see it as a problematic policy. They may support it but are really skeptical when it comes to an individual case," said Richard Dieter, DPIC's executive director, in a phone interview "... There are alternative punishments; it's not like people are getting away with anything."

Exonerations--most through modernized methods of evidence gathering such as DNA matches--has added to the doubt surrounding the efficacy of executions. Minorities, poor people and the mentally ill are disproportionately represented on death rows throughout the nation. In the United States, some 1,040 people have been exonerated for crimes since 1989, including 13 in Mississippi, reports the National Registry of Exonerations, a joint project of the University of Michigan Law School and the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law.

The cost of pursuing a death-penalty case is a consideration. "To do a death-penalty case is a big investment," Dieter said, adding that when states are cutting budgets for necessities such as education, the cost of death-penalty convictions is "not productive."

California, for example, currently has 724 inmates on death rows, and its courts continue to impose the death penalty, yet the state has not executed a prisoner since 2006.

"Using conservative rough projections, the Commission estimates the annual costs of the present (death penalty) system to be $137 million per year," wrote the California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice in 2008. "The cost of the present system with reforms recommended by the Commission to ensure a fair process would be $232.7 million per year."

The DPIC concluded its report by stating what should be obvious to many: " When a law is so rarely imposed, and the rationale for its imposition discredited, its continued use is placed in doubt. ... [T]he death penalty appears to be an increasingly irrelevant component of our criminal justice system."

Comments