When Republican John R. Lynch won a seat in the Mississippi House, the Legislature had a lot of important rebuilding to do after the Civil War, including schools and other public buildings. In fact, state government needed to entirely reconstruct and reorganize itself.

"To accomplish these things, money was required. There was none in the treasury. There was no cash available even to pay the ordinary expenses of government," Lynch wrote in "Reminiscences of an Active Life," his memoir, available at the Leland Speed Library at Mississippi College.

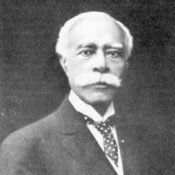

Born in 1847 to a white father and mixed-race slave mother in Louisiana, Lynch managed a photography business in Natchez. His first education came as a result of eavesdropping on lessons taught at the all-white school across the alley from his shop.

In April 1869, Gov. Adelbert Ames appointed Lynch justice of the peace; he was 21. The same year, Lynch became the youngest House speaker and the first black man to hold the leadership post.

Even as a Republican in a state that the party of Lincoln controlled in the years after the war, Lynch's nomination for the speakership was far from a sure thing.

In "Reminiscences," Lynch recounts how several members of his caucus refused to support his speakership. It took several days and a personal plea from Republican former Gov. James Alcorn, who by then was serving in the U.S. Senate, to break the deadlock.

The fracas did not embitter Lynch, who remained a staunch loyalist through his life. He reportedly later declined to serve in the Cabinet of President Grover Cleveland because he was a Democrat.

"In the organization of the House, the contest was not between white and colored but between Democrats and Republicans. No one had been elected, at least on the Republican side, because he was a white man or because he was a colored man but because he was a Republican," Lynch wrote in his memoir.

In 1871, Lynch was tasked with reapportioning the state's six congressional districts. He faced two options. The first was to make six Republican districts but with his party having only slim majorities in two. The other option, which he eventually favored, was to make five Republican districts and concede one to Democrats.

His time as speaker was brief. After Lynch ran successfully for Congress, another African American Republican, Isaac D. Shadd, became speaker.

Little about Shadd's life, much less his time in the Legislature, is known. Born in Delaware, Shadd and his sister, Mary, immigrated to Ontario, Canada, sometime between 1850 and 1851 around the time Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act.

Together, the siblings ran an antislavery newspaper called the Provincial Freeman.

Later, Shadd moved to Vicksburg, Miss., winning a seat in the House in 1871 and serving until 1876 when Democrats wrested control of the Legislature. That same year, Democrats redistricted Lynch out of his congressional seat as well.

After Reconstruction, Lynch went on to serve as Republican State Executive Committee chairman and as a delegate to the Republican National Convention. In 1884, Lynch became the first African American to deliver the keynote address at a major party's nominating convention, and he later traveled the world as an officer in the U.S. Army.

Later in life, Lynch became disenchanted with his once-loved Republican Party. Of his disappointment, he wrote: "The author is of the opinion that a large majority of the colored Americans will affiliate in national elections with the Republican party when that party will again assume the championship of human rights regardless of race or color."

Lynch died in 1939 in Chicago; Shadd in 1896, reportedly in Greenville.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus