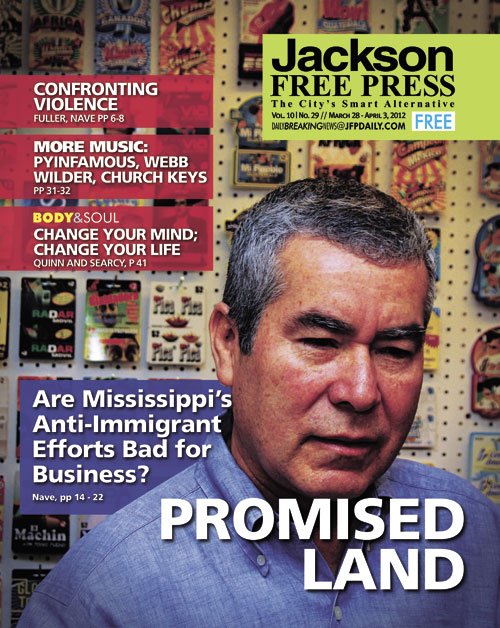

Israel Martinez sat patiently in his car as police officers inspected a half-dozen vehicles ahead of him, shining their flashlights in the faces of the drivers and letting them go one by one.

It was around midnight on May 19, 2011, and Martinez was heading home after a long day of moving his businesses to a larger location on Old Canton Road in Ridgeland. When the light shone on Martinez's young, angular brown face, the then-25-year-old brandished his vehicle insurance card and International Automobile Drivers Club card as proof of his identity.

Then a cop asked him the question he'd somehow managed to avoid in the seven years since he arrived in the United States from Veracruz, the Mexican port city where he grew up: "Are you here illegally?"

Martinez answered that he was in the process of acquiring the paperwork that would make his being here legal. Police took Martinez into custody and booked him into the Madison County Jail around 2 a.m.

For the lesser infraction of driving without a valid driver's license, the Canton cops slapped him with a $300 citation, which friends rushed to the jail to pay.

But his troubles had really only just begun. Because he was in the United States illegally, the police loaded Martinez and others, mostly fellow Spanish speakers, caught in the dragnet, into a small van and headed for an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Pearl. From there, they boarded an even larger van with even more Spanish speakers bound for an ICE regional detention center in the Tensas Parish, La., town of Waterproof.

Martinez recalls the palpable sadness among the frightened people as ICE's drivers barked ethnic slurs about "f*cking Mexicans," even as the detainees represented a cross-section of Central and South American nations, including Brazil. Women, Martinez said, were told they would never see their children again.

"They treat you like a killer," he said of the verbal abuse—what he considers as "psychological violence"—and the tight shackles that cut into his wrists and bound his hands at his waist.

In the Tensas facility, which takes in ICE detainees from Mississippi and Louisiana, Martinez was surprised to find guards who were more humane than their transporters had been. There, an ICE official tried to make him sign a voluntary deportation form, but because he had done his homework in preparation for this day, he knew that he had the right to see a federal judge and refused to sign the paper.

Others just signed the form (Martinez sensed they would just sneak back over the border in a week or two), and those who didn't had to pay fines between $5,000 and $20,000 or they would sit until jail until the judge would see them.

Martinez was lucky. The businessman had about $3,000 in cash that he could use toward his $5,000 fine. The same friends who paid his traffic ticket again came to his rescue to supply the remainder.

Four days after his arrest, Martinez returned to Jackson to continue running his businesses. As a result of his detention, ICE issued Martinez a photo ID, documentation that he is officially in the custody of federal authorities, which protects against immigration double jeopardy.

While Martinez waits to see the judge, he cannot be arrested again due to his status, and he can continue providing for his family.

No Choice But Work

Martinez left Mexico when he was 17 to join his mother who came to the U.S. on a temporary work visa, first in Washington state and, then, in Mississippi. With Mexico's languishing economy offering few opportunities for industrious young people, Martinez decided she would attend college in the U.S., and his mother paid a man to arrange what he believed would be his legal immigration into the country.

But when Martinez and others showed up, it became clear they would be smuggled across the border. If he backed out, he would lose his money. When he got to Mississippi in 2003, his lack of a Social Security number precluded him from enrolling in college.

"I had no choice but to work," Martinez said an interview in his conference room in Ridgeland.

Actually, he did have choices. He could have returned to Mexico or copied the behavior of many of his American-born peers and mooched off his mom. Instead, he went to work at her side at a local chicken plant he declined to name and other companies, putting in up to 18-hour workdays.

"It's hard. It's nasty. The pay is little," he said.

From Martinez's paltry $320-per-week salary, the company deducted state and federal income taxes. Calculated into the monthly rent of the three-bedroom home he lives with his mother and three siblings are property taxes that help fund local schools. Like regular Americans, the Martinezes and other immigrant families get their groceries from Walmart and Kroger; Northpark Mall is a favorite weekend destination of immigrant teens and Americans alike.

By early 2008, Martinez had had enough of the chicken plant and his four other jobs that included working in a warehouse, for a construction company and volunteering at a computer shop. Despite the low wages he had earned, he demonstrated the fiscal responsibility to tuck away $5,000 to start a computer repair business.

"You don't have to have a lot of money to save; you have to have good management," Martinez said.

He estimates that his computer business, Kismar, which can do everything from fix network connectivity problems to building new Pcs from scratch, spends between $5,000 and $10,000 per month on parts.

In 2009, he launched another business, now called Lingofest, for locals who want to learn Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian or English. Most of his clients are young, transplanted professionals. Businesses with sizable native Spanish-speaking work forces can hire Martinez's company to provide interpreters or to serve as a cultural liaison. A growing portion of his business also assists companies in marketing products to central Mississippi's small but growing Latino population.

During his first year of operation, Martinez received about 15 anonymous calls telling him that he should shutter Lingofest; the calls have since ceased.

The two signs that hang above his door cost $3,000 each, which he paid to a local company. In total, he estimates his businesses pull in $145,000 in income yearly, which he pays taxes on using an IRS-issued individual taxpayer identification number, or ITIN.

At 26, Martinez is living the American Dream—not taking Americans' jobs. Using his labor and intellectual capital, he filled a niche in the market to meet American demand, which in turn, has pumped thousands of dollars into Mississippi's economy over the years.

If he had been born in Europe at the turn of the 20th century, we would exalt his story as symbolic of the American ideal. If his family's roots were in India or Cuba, he might be urged to run to run for elected office. Instead, some elected officials are spearheading a movement to run people like Martinez out of Mississippi.

Targeting 'Aliens'

Just before midnight on Wednesday, March 14, the Mississippi House of Representatives began floor debate on House Bill 488. Coming a year after a similar attempt failed, the act asserts that the state has a "compelling interest" to "discourage and deter the unlawful entry and presence of aliens and economic activity by persons unlawfully present in the United States."

More than 40 states have tread into immigration on everything from implementing immigration status verification requirements for employers to reining in human trafficking. The models for the Mississippi newest version are laws enacted in other states, most notably Arizona and neighboring Alabama. Utah, Indiana, Georgia and South Carolina followed Arizona's example by enacting broad-reaching immigration.

The controversial Arizona law, for example, requires all law-enforcement personnel to determine the immigration status of anyone they come into "legitimate" contact with. The Alabama law requires law enforcement to determine the status of any person they suspect is undocumented and says immigrants must produce authorizing documents on demand.

Rep. Andy Gipson, R-Braxton, chairman of the House Judiciary B Committee, changed the bill, which fellow Republican Becky Currie of Brookhaven introduced, to apply only to arrests. Its original language closely mirrored laws enacted in other states, even taking its official title, the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, from Arizona.

In some ways, legal challenges to other states' laws made the Mississippi House bill passed weaker than what supporters wanted. Lawsuits have successfully blocked parts of Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina and Utah's laws. The US Department of Justice filed complaints in four of those states, including Arizona—a case that the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments on this summer.

To get around the constitutional issues those laws raised, Gipson modified the language to require law enforcement to check the status of suspected "illegals" after they are arrested, presumably for an unrelated crime.

HB 488 would require police officers to make a "reasonable attempt" to determine the immigration status of anyone they arrest—if officers have "reasonable suspicion" that the suspect is in the country illegally. If the suspect is undocumented and is convicted, the bill says, law enforcement then must notify federal immigration agents about the suspect's status.

The state can also transport the prisoner directly to the ICE office, but the law does not require it.

Karen Tumlin, managing attorney for National Immigration Law Center in Los Angeles, said the vagueness of the reasonable suspicion language, which is currently only in effect in Alabama, has confused police agencies across the country.

"Reasonable suspicion is a concept that law enforcement is familiar with," Tumlin said. "The problem is that reasonable suspicion usual goes to a crime, something you can measure. Reasonable suspicion that you are unlawfully present is not something you can observe."

HB 488, which Tumlin characterizes as "very far-reaching," (she added that her organization would sue if Mississippi passes the bill) also indemnifies law enforcement from civil lawsuits for enforcing, or not enforcing the law, as long as their actions or inactions are in "good faith." HB 488 also says that race, color, and national origin cannot be used to enforce the act and that "the immigration status of any person who is arrested shall be determined before the person is released." Proof of legal status, under the act, includes a Mississippi driver's license or state ID card, a tribal enrollment card, or an ID from another entity that requires proof of legal residence to issue it.

Bear Atwood, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi, said police might interpret the lack of an ID or the possession of a foreign ID as reasonable suspicion that a person is in the country without documents.

"If someone gets detained while the police check their immigration status, that's not 20 minutes on the side of the road. That can take days," Atwood said.

Riding in an overcrowded car or hanging out in areas known for having a high frequency of undocumented immigrants could also provide a legal basis for reasonable suspicion, said Justin Fox, a staff attorney with the ACLU's Immigrant Rights Project.

Although much care was taken to protect police officers and local governments from civil lawsuits for enforcing the law, it also provides some recourse for legal residents against a government agencies that limit or restrict the enforcement of federal immigration laws. The award for such a failure, under the act, would be no less than $500 but no more than $5,000 per day that the law remains in effect after the plaintiff filed their complaint.

The act also forbids business transactions, including applying for or renewing a car tag or driver's license, between unauthorized immigrants and the state government but carves out an exception for international business executives. The high-profile arrest of Detlev Hager, a German Mercedes-Benz executive, in Alabama caused the state much negative publicity and embarrassment.

Alabama's law prohibits businesses from employing unauthorized immigrants and prevents anyone from transporting, concealing, harboring or housing them unless they are providing child-care or emergency services. Mississippi did not include those provisions.

Groups like the Federation for American Immigration Reform support state-led immigration efforts because, in their view, the federal government has been derelict in enforcing immigration. "While immigration is a federal government issue, the state level is where the bills get paid," said FAIR spokesman Ira Mehlman, who is based in Seattle, Wash.

FAIR would like to see the federal government slash the rate of immigration from the current level of 1.1 million per year down to 300,000. The organization's stance is that the presence of unauthorized immigrants hurts American workers, contributing to an already-saturated market for low-skilled labor and driving down incomes for Americans. These workers also perpetuate degraded health and safety conditions, which discourage legal residents from seeking the jobs.

"It's not the jobs, it's the wages and working conditions that Americans reject—and they should reject them," Mehlman said.

Supply and Demand

When people think of places that might be attractive to immigrants, few think of Mississippi. New York City, Chicago, and Seattle are logical because each has a large, diverse immigrant population and, despite early cultural clashes, long histories of welcoming new residents from other nations. The idea of immigrants also makes sense in the border states of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas or in places like Florida, where the influx of Cuban immigrants since the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s created a Latino-friendly culture.

Bill Chandler, executive director of the Mississippi Immigrants Rights Alliance and longtime labor organizer, came to Mississippi from Texas in 1989, a time when there were just two Mexican restaurants in the state.

A Los Angeles native who worked on labor organizing campaigns with Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in the late 1960s, Chandler has observed immigrants swell in numbers, partly because of supply-and-demand economics that resulted from old-fashioned southern racism.

Throughout most of Mississippi's history, Chandler explains, African Americans supplied their labor to cultivate crops like cotton and sweet potatoes. But state-sponsored racial violence and intimidation spurred the exodus of hundreds of thousands of blacks from the Deep South, leaving too few laborers in Mississippi's fields.

In the early 1980s, then-Gov. William Winter pushed through his Education Reform Act of 1982, which leveled the playing field between funding black and white schools. Black graduation rates in the state rose, and more African Americans graduated from high school, went on to college and entered high-wage professions. White Mississippians didn't fill the void, resulting in even fewer field hands.

When blacks left these jobs, immigrants from Mexico and Central and South America began filling the vacuum, slowly at first but more quickly in the mid-1990s when President Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement.

NAFTA's original purpose was to promote economic development in Spanish-speaking North America but seemed to have the opposite effect. American agribusinesses moved into the Mexican countryside and pushed small family farms out of business. Many factories in Mexico—and the U.S.—moved to China.

In Mexico, NAFTA helped displace millions of workers. Meanwhile, the financial capital from America's high-tech sector opened up even more opportunities for native-born Americans to make money in ways other than slaving away in poultry factories.

Trying to build support for their efforts, immigration reformers have long maintained that immigrants, willing to work for below-market wages, pushed African Americans out of certain industries.

Dr. Steven Pitts, an economist at the University of California at Berkeley, tackles the black-brown labor gap in a paper titled, "A Note on the Research Concerning Blacks, Immigration and Employment. If it were true that foreign-born workers under-priced blacks out of work, Pitts reasons, cities with massive immigrant populations should have higher-than-normal black unemployment and lower wages—but that's not necessarily true.

Pitts examined the black unemployment rate in 13 cities compared to the size of foreign born in the work force. In Birmingham, Ala., which had a 4.3 percent foreign-born work force in 2007, black unemployment stood at 12.3 percent. In Memphis, black unemployment stood at 28.3 percent with a foreign born population of 6.1 percent. However, Miami's work force was 45.7 percent foreign-born, yet the black jobless rate remained at 10.4 percent, demonstrating no connection between the two.

Between 2000 and 2010, Latinos increased their numbers 106 percent in Mississippi, the Pew Hispanic Center reports. In fact, Latinos expanded more rapidly in the South than all other regions with Alabama's rate accelerating the fastest in that period, at 145 percent.

Anyone curious about the economic benefits that immigrants bring to Mississippi need just turn their attention eastward to Alabama, which passed HB 056 in 2011.

In January, the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa's Center for Business and Economic Research published a cost-benefit analysis of that state's anti-immigration law.

Dr. Samuel Addy, who authored the study, concedes that the departure of immigrants might yield some benefits in terms of savings on health care and education, increased safety for legal residents and more opportunities for legal U.S. residents.

From what we do know about the behavior of undocumented immigrants—who avoid hospitals and, contrary to stereotypes, have fewer children than Americans—Addy believes that any effect their numbers have on health-care costs is minimal. However, quantifying those benefits is nearly impossible because no reliable data exists on the size of Alabama's undocumented population.

Measuring the costs of the Alabama law—or, to put it another way, the benefit of immigrant presence—is much easier for a reason so simple that even a state lawmaker who's only taken freshman economics can understand it: the law of demand.

"The economy is made up of people, institutions and property—that's all it is. And anybody who tells you otherwise does not know much economics," Addy told the Jackson Free Press. "Because of the people, there is demand in the system. The more income that people make, the more they can demand. And that's how the economy grows."

Since economies are demand-driven, any policy that reduces demand will shrink the economy, no matter how well intentioned, Addy said.

Assuming the proponents of the Alabama anti-immigration law got their wish and 80,000 "illegals" suddenly vanished from the state, Addy estimates a loss of 59,536 jobs for a total reduction of nearly 140,000 positions.

Let's say those 80,000 people earned $25,000 per year—that's a $7.7 billion hit to Alabama's gross domestic product, another $189 million in state sales- and income-tax loss, and $66.5 million in city and county taxes, according to Addy's analysis.

"Instead of boosting state economic growth, the law is certain to be a drag on economic development without considering the costs associated with its implementation and enforcement," Addy wrote.

Rodney Hunt, a Jackson dental surgeon, and director of the Mississippi Federation for Immigration Reform and Enforcement, believes Addy's cost-benefit study is flawed.

"It's a misconception that Americans won't do certain jobs. Americans will do the jobs if they're offered a fair wage for the work that they do," Hunt said.

Hunt points to Alabama, which saw its unemployment rate dip from 9 percent in September 2011, when the state implemented parts of its immigration law (a federal judge blocked some provisions from going into effect), to 7.8 percent in January 2012. However, the Alabama trend closely mirrored the national unemployment situation, which was also at 9 percent last September and now stands at 8.3 percent.

Addy's economic analysis of the Alabama law also considers the added costs for law enforcement to pull over and detain every Mexican-looking vato they encounter, not to mention whatever damage is done if tourists and businesses stay away from the state they perceive is run by xenophobic bigots.

Ultimately, Addy believes Alabama and Mississippi's anti-immigration policies undermine a core American ideal: freedom.

"I mean, we talk about human rights to the rest of the world, and then we turn around and do this to our own people?" Addy said.

ALEC's Invisible Hands

No discussion of immigration, or many other state legislative proposals, is complete without talking about the powerful influence of the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC.

Corporations, trade associations and state lawmakers pay to join ALEC. When a corporate member wants a law passed, ALEC sets them up with a like-minded legislator to introduce one of the hundreds of ALEC-written model bills prepared on subjects ranging from tort reform to virtual schools.

Immigration is one of ALEC's signature issues. (Others include the renewed push for charter schools, voter identification and tort reform in Mississippi.

The progressive nonprofit investigative journalism group Center for Media and Democracy, headquartered in Madison, Wis., provides most of what is known about ALEC. The group maintains an extensive database of ALEC model bills and other information on the organization at http://www.alecexposed.com.

At least two of ALEC's bills related to immigration were introduced in some form during the current Mississippi legislative session.

HB 488 and HB 1153, which died in committee, are nearly identical to ALEC's Immigration Law Enforcement Act and No Sanctuary Cities for Illegal Immigrants and Safe Community Police Act, respectively.

"It is an organization funded by large corporate interests in order to push their agenda. Most people are too busy making a living to worry about what ALEC is doing," said House Minority Leader Bobby Moak, D-Bogue Chitto. He has attended ALEC gatherings and once received one of the group's scholarships to attend a conference at Disney World.

Despite having once been a member, Moak isn't certain which of his fellow legislators are also in ALEC, which remains tight-lipped about its member roster and how exactly it gets money.

Kaitlyn Buss, who handles public relations for ALEC, told the Jackson Free Press in an email that the group doesn't publicize its member list. She did not immediately respond to follow-up requests for an interview with the organization.

However, a review of ALEC's IRS records provides some insight into where the big money it funnels into state Legislatures comes from. In 2010, ALEC collected $7 million in revenue, including $1 million from conferences, $84,883 from member dues and another $6 million from contributions, gifts and grants, according to tax records.

The Center for Media and Democracy estimates that member dues represent only 2 percent of ALEC's revenue, and the rest comes from corporate members paying from $7,000 to $25,000. A sizable chunk also comes from conservative foundations, including the Charles G. Koch Foundation and Claude R. Lambe Foundation—both connected to the billionaire oil baron Koch family—as well as the Allegheny Foundation and the Castle Rock Foundation, which has ties to the beer magnate Coors family.

ALEC's board of directors consists of two legislative chairmen from each state. In 2010, Mississippi's chairmen were former Republican lawmakers Sen. Billy Hewes III, R-Gulfport, and Rep. Jim Ellington, R-Raymond. Hewes unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor in 2011 against then-state Treasurer Tate Reeves while Ellington lost his seat in the recent November election to Democrat Brad Oberhoausen.

The Mississippi ALEC legislative chair positions are currently vacant, ALEC spokeswoman Buss said.

Ron Scheberle, who runs the Irving, Texas-based political services firm Scheberle & Associates, serves as ALEC's part-time executive director, collecting $204,000 per year for 25 hours of work per week.

State records show that Mississippi taxpayers paid ALEC $2,950 between 2006 to 2008 for employee training at the state Department of Marine Resources, the Division of Medicaid, and the governor's office. The Jackson Free Press has submitted public-records requests to the agencies to determine the nature of the trainings.

Former Pascagoula Rep. Brandon Jones, a Democrat, has been critical of ALEC's presence in Mississippi. Now executive director of a political action committee called the Mississippi Democratic Trust, Jones calls ALEC "a cynical vehicle for memorializing partisanship on the state legislative level."

Voters, he said, should take notice, because Mississippi lawmakers appear to be offering copy-and-paste ALEC bills with little input from their constituents. "People might be ready to accept shocks and brakes from an assembly line," Jones said.

"They're not ready to accept an assembly-line approach to their laws."

Interestingly, many of the same corporations who appear to be ALEC members are also members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has taken a number of conservative stances in recent years—and pumped a lot of money into congressional campaigns and Mississippi political races to help Republican candidates, including Mississippi Supreme Court justices. But the U.S. Chamber has shied away from state-level immigration reforms such as the bill Mississippi is now considering.

The Chamber has a quiet initiative called the Essential Workers Immigration Coalition made up of agricultural product trade councils that criticize local and state-focused immigration efforts like HB 488. Their argument: Leave immigration enforcement to the federal government.

According to information from the EWIC, state Legislatures enacted 84 bills about immigration in 2006, and more than double that number, 170, in 2007. "Many of these bills seem to contradict federal immigration laws, confusing employers and even state labor department officials," reads a statement bearing the U.S. Chamber's logo on the EWIC website.

"This wave of legislation includes mandates for employers prohibiting the employment of undocumented workers, imposing penalties for non-compliance and requiring work-authorization verification, sometimes beyond what Congress requires," the statement says.

The legislation also includes proposals to eliminate state services and benefits to undocumented immigrants, new mandates on state and local law enforcement, and demands for federal action."

Diminishing Returns

Hernan Bermudez, 60, is seeing the effects of anti-immigrant fervor on his business' bottom line. Bermudez, who owns La Guadalupe taqueria and a grocery store of the same name specializing in products from South America and pre-paid phone cards, said the recession coupled with talk of immigration reform has been a one-two punch for his businesses in the past three years. "Mississippians are not racist. I think the people like the immigrants. It's the politicians," Bermudez said.

Bermudez emigrated—legally—from Cali, Colombia, with his wife and young son 17 years ago to escape the violence of the notorious drug cartels of the early 1990s.

After a year-long stay in Miami, Bermudez, who had been an industrial engineer for Goodyear in Colombia, moved the family to Forest and became a poultry plant supervisor. Eleven years ago, Bermuduz opened a small grocery store in south Jackson. Over the next several years, he would open six stores throughout Mississippi in Jackson Philadelphia, and Ripley. He also earned his American citizenship.

When the economy worsened, Bermudez closed or sold off all the businesses except La Guadalupe, near Old Canton Road and County Line Road.

Bermudez also went from having eight employees down to six. He approximates that 60 percent to 80 percent of his business relies on immigrants.

If Mississippi follows Arizona and Alabama, Bermudez does not think he will be able to build his businesses back up to their pre-recession level.

"The politicians and media are making comments like, 'The immigrants are causing the economic downfall.' It's not good because those people are working," Bermudez said.

"Most politicians need to learn about the different cultures. They have to know that people come here to work, to invest. If they're living here, they are spending their money here in Mississippi."

|

|

|

Pew Hispanic Center

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus