Astonishing. Remarkable. Sinister. Those are words that come up again and again when confronting the wave of voter-identification laws that has swept through more than 30 Republican-dominated state legislatures in recent years. The measures sound innocuous enough: When a voter shows up to the polls on Election Day, he or she must present valid photo ID to cast a ballot.

The goal, proponents say, is to combat in-person voter fraud--claiming to be someone you're not and entering a vote in their name. But study after study, including an exhaustive investigation by the Arizona State University's Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, has found almost no evidence that in-person voter fraud occurs. Culling through 5,000 documents over 10 weeks, the News21 project found only 10 cases of in-person voter fraud since 2000: about one case for every 15 million eligible voters.

What's more, independent analyses has repeatedly shown that requiring state or federally issued ID at the polls imposes a disproportionate burden on very specific demographics: the poor, the elderly, students and people of color.

"We've heard it time and time again; it really is a solution in search of a problem," said Stephen Spaulding, Washington D.C.-based staff counsel for the nonprofit citizen's lobby group Common Cause.

"We do have election administration problems in the country--with machines breaking down, assuring that votes are counted accurately--and we need to focus our attention there," he said. "This threatens everyone's right to a free and fair election."

Barred at the Ballot Box

If there's anyone approximating a symbol of what's wrong with what are referred to as "restrictive" or "strict" photo ID laws, it's Viviette Applewhite. At 93 years old, Applewhite is an African American Pennsylvanian who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and has cast her ballot in almost every election since the 1960s.

Her purse was stolen years ago and with it, her Social Security card. What's more, because she was adopted as a child, the name on her birth certificate differed from that used on other official documents. Her adoption itself lacked any kind of record.

Under Pennsylvania's voter-ID law, which was passed in March 2012 and has since become a legal lighting rod in the battle over voting rights, Applewhite could not obtain the required identification to participate at the polls.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, the Advancement Project, the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia and the D.C.-based law firm Arnold & Porter took up Applewhite's case and the cases of others the law affected similarly. The lawsuit, which alleged the state's voter-ID law violated Pennsylvania's constitution by denying citizens the right to vote, was denied a preliminary injunction and bounced on appeal from district court to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which sent the challenge back to the lower court for reconsideration.

On Oct. 2, Robert Simpson, a judge for the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania, granted the preliminary injunction, allowing people like Applewhite to vote in the 2012 election without photo ID and without having to cast a provisional ballot--a measure that, in the some states, allows non-ID holders to vote, but which requires them to return to the polling place after the election to confirm their identity.

Barring any further litigation, Pennsylvania voters will be required to present photo ID in future elections but for now, Applewhite and others in her situation will be free to vote as they always have. In fact, as the case was being appealed in August, Applewhite received an ID using her 20-year-old Medicare card, proof of address and a state document affirming her name and Social Security number. (The process also required her to take two buses to the licensing office, according to media reports.)

That's a lot of hassle to exercise a right Applewhite has enjoyed for 50 years, but she's not alone. According to best estimates, strict voter-ID laws could effectively disenfranchise millions of voters if adopted nationwide.

The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University found that as many as 11 percent of adult U.S. citizens do not have any form of government-issued photo identification, accounting for more than 21 million people. Among that group, 18 percent of citizens 65 years of age or older don't have government-issued photo ID (more than 6 million seniors) and, based on 2000 U.S. Census figures, more than 5.5 million African American adults lack photo ID--a full 25 percent of eligible black voters. Meanwhile, U.S. citizens, regardless of ethnicity, age or gender, who make less than $35,000 "are more than twice as likely to lack current government-issued photo identification as those earning more than $35,000 a year," the Brennan Center reported, adding that that means at least 15 percent of voting-age Americans in the low-income bracket lack valid ID.

On top of that, the Brennan Center found in its survey that as many as 7 percent of voting-age citizens (more than 13 million adults) don't have ready access to documents proving that they're citizens, making the process of getting valid ID all the more complicated.

"These ID laws, and this notion that they don't impose a cost on citizens is farcical," said Spaulding, with Common Cause. "We know that in some states, it costs money to get documents and get an ID. There are a number of voters who are in a catch-22; they're 90-years-old, they were born at home with a midwife and they don't have a birth certificate. There's the expense of getting those documents, there's the expense--especially in rural areas--of making the trip to get the ID. This notion that these IDs are 'free' does not pass the smell test."

But it's on that notion that voter-ID laws have been ruled constitutional.

In 2008, the United States Supreme Court upheld Indiana's restrictive voter-ID law, which is seen as the test case for similar laws nationwide, because the court found the law was not burdensome to voters.

"Clearly, that's not the case," Spaulding said.

Sneak Attack

It doesn't take much analysis to figure out the upshot of proliferating voter-ID requirements: fewer seniors, students, people of color and low-wage earners at the polls. And it doesn't take much to see who would most benefit from a whiter, more middle age, affluent electorate.

"I don't think it's a coincidence that the legislators carrying these bills are not Democrats," said Lisa Graves, executive director of the nonprofit watchdog group Center for Media and Democracy.

According to Graves, whose organization has made voting rights a priority issue, this newest push to limit the franchise traces its roots to the 1990s and the enactment of the National Voter Registration Act, or "Motor Voter," under President Bill Clinton. The measure did exactly what its name implies: It made it easier for voters to register. African Americans, particularly, registered in high numbers, Graves said, prompting backlash among conservative states.

"In response to that law, southern states started proposing changes to the laws to make it harder to register. Those bills went nowhere; they were perceived as racist ... and sort of languished for a number of years," she said.

Then came the election of President George W. Bush, "and the right wing started pushing this theme of voter fraud," Graves said. The Bush administration even tried to redirect the voting-rights section of the civil rights division to push this idea of voter fraud, she added.

"U.S. attorneys were fired because they didn't do enough to assert non-existent voter fraud," Graves said.

Despite pressure from the new Bush administration, strict voter-ID laws remained few and far between, with only Indiana and Georgia enacting restrictive ID measures in 2005. But, Graves said, "These things were bubbling."

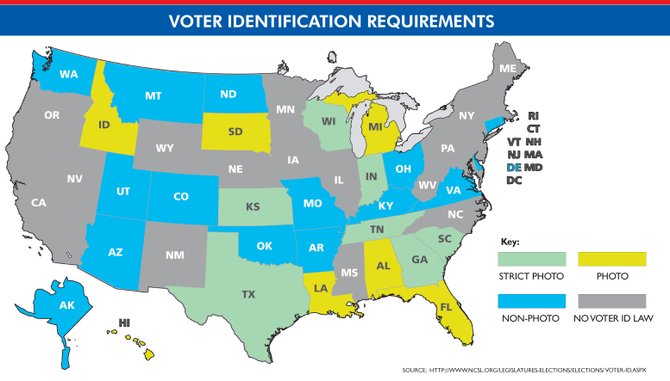

When Barack Obama won the 2008 presidential election, it was in large part due to huge voter turnout in cities and among students and African Americans. Republicans, having lost the White House, also found their party losing ground in state legislatures. Project21 found that 37 state legislatures introduced 62 voter-ID bills since 2009, with the bulk of the measures introduced or adopted in 2011 and 2012. Both the Brennan Center and Project21 found that a handful of states have active, strict photo ID laws for voters and more than a dozen others are pending--either hung up in court, awaiting preclearance from the Department of Justice or too recently enacted to be in effect.

"It's remarkable," said Jennie Bowser, Denver-based senior fellow with the National Conference of State Legislatures. "I've tracked election legislation since late 2000 and everything that happened in Florida, and I've never seen so many states take up a single issue in the absence of a federal mandate."

Graves, meanwhile, fingers the culprit.

"Suddenly the Indiana law was dusted off the shelf and put out there as a national model that every state should be pushing," she said, "and ALEC is behind it."

The Bill Mill

ALEC stands for the American Legislative Exchange Council, and according to some, it is nothing less than a shadow lawmaking body that draws its strength from an ocean of corporate money. If the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United can be said to have opened the flood gates to corporate cash in American politics, then ALEC is trying to turn on the flood.

"ALEC isn't simply a think tank or a gathering of lawmakers: It is a corporate-funded operation that pushes a corporate message and a conservative message," said Graves, of the Center for Media and Democracy, which in July 2011 made public 800 internal documents on its website, AlecExposed.org, proving ALEC's cloaked hand in crafting "model legislation" meant for introduction in statehouses around the country.

"At its core it is a way to take some of these ideas that a think tank might fancy and operationalize them," she said. "And I use 'operationalize' very purposefully."

A call to ALEC's media relations representative for this story went unanswered, but the organization's ideological bent is clear enough. On its website, ALEC says it "works to advance the fundamental principles of free-market enterprise, limited government, and federalism at the state level through a nonpartisan public-private partnership of America's state legislators, members of the private sector and the general public."

Registered with the Internal Revenue Service as a 501c3 nonprofit, ALEC boasts around 2,000 member legislators--the vast majority being Republicans--who pay a nominal fee for membership, and upwards of 300 corporate and other private-sector members who pony up between $7,000 and $25,000 for the privilege of getting together with sympathetic lawmakers at lavish retreats.

Broken up into task forces focused on various aspects of public policy--from education to civil justice and the environment--ALEC members, both from the public and private sectors, get together and write model bills, which they then vote on and, if ratified, ALEC legislators carry them home for introduction in their respective states.

The strategy has been successful. ALEC brags on its website that each year lawmakers introduce about 1,000 pieces of ALEC-written or ALEC-inspired model legislation in the states. An average of 20 percent of the legislation becomes law.

Despite this, ALEC has remained largely under the radar, even though the organization has been active for nearly 40 years--archconservative Paul Weyrich, who also co-founded the Heritage Foundation, established ALEC in 1973. Nonetheless, its impact on policy in the states reads like a greatest hits compilation of the most controversial bills in recent history: from changes to U.S. gun laws like the Florida "stand your ground" legislation made infamous by the Trayvon Martin shooting (a measure that was crafted with help from the National Rifle Association, a prominent ALEC member), to state-based efforts at overturning or circumventing the Affordable Care Act, to recent measures limiting teacher union powers and handing portions of student instruction over to for-profit education companies. Even Arizona's hotly contested immigration law--SB1070--started life as an ALEC-approved "model" bill.

"There's a whole set of bills that are advancing that corporate agenda to privatize prisons, privatize education--and by privatize I mean profitize," Graves said.

Profit is the Name of the Game

ALEC's IRS filings from 2007 to 2009, made public by CMD, show that the organization raked in more than $21.6 million from corporations (with members including Exxon Mobil, Altria, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer); foundations like the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation; and nonprofits including the NRA, Goldwater Institute and Family Research Council. In all, private-sector contributions account for nearly 98 percent of ALEC's funding, while the dues paid by member lawmakers, pegged at about $50 each, came to just more than $250,000 or about 1 percent of its haul during the same time period.

In exchange for these hefty--though tax-deductible donations--ALEC's private-sector members get to ensure that individual pieces of ALEC legislation, by and large, serve a narrow band of very specific corporate interests: education measures benefit for-profit education firms and harm unions; health-care measures benefit insurance companies and drug manufacturers; tort reforms benefit corporations in general by limiting their liability to consumers.

More "insidious," as Graves put it, is ALEC's drive against voting rights.

"It's deeply cynical and quite sinister--an outlandish effort by ALEC and others to make it harder for Americans to vote," she said. "At the end of the day, depending on which analysis you're looking at ... it's possible that these measures remove maybe 1 percent from the pool of votes that would be part of the election. You still have an election, but you've shaved off this percentage; you have the appearance that you have an election."

Analysis by Project21 found that more than half of the 62 strict voter-ID bills introduced in legislatures since 2009 were based on (or copied from) ALEC's sample voter-ID bill, which was ratified by the group's membership that same year.

These measures serve no particular business master, rather, they strike at the final weapon the public possesses to stem the tide of corporate-crafted legislation: access to the ballot box.

"The essence of a democracy, and the essence of a representative democracy in the United States, is that we elect people to represent people," Graves said. "The question is whether our representatives are going to represent us, or if they're going to represent the interests of global corporations and, in some cases with ALEC, foreign corporations."

As for why big business would support limiting the franchise, the equation breaks down pretty simply: Corporations want to bring down barriers to doing business, and Republicans are more than happy to oblige. If Republicans don't win elections, then corporations don't see those barriers lifted. The solution: Eliminate the competition. If voting rights get in the way, well, like the notorious mob accountant Otto Berman once said, "Nothing personal; it's just business."

"I think it is a little more class-oriented," said Alexander Keyssar, professor of history and social policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and a frequent speaker and writer on voting-rights issues.

"The core interest in the suppression that's going on is partisan, it's not racial," he said. "If African Americans voted predominately Republican, or 50/50 Republican, I don't think their neighborhoods would be targeted for suppressive efforts. I think that it's a community that now votes 95 percent Democrat and if you want to knock out Democrat interests that's a good place to start."

Most important, though, is that suppressing voting rights doesn't hurt the bottom line.

"You can be a customer who votes or a customer who doesn't vote," Keyssar said. "It doesn't cost (corporate interests) anything."

Pushback

With increasing media scrutiny and public outrage, ALEC's operations--and specifically its voter-ID push--may well hurt both its bottom line and the bottom lines of its corporate members.

In the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting in Florida earlier this year, nonprofit civil-rights group Color of Change leveled criticism directly at ALEC for crafting the "stand your ground" law and called on its members to urge corporations to drop their support for ALEC. To date, 41 corporate ALEC members have stopped funding the group, including big names like Walmart, Coca Cola, Kraft, Amazon, Johnson & Johnson and General Motors.

Following exposes by CMD, Common Cause, The Nation magazine and others highlighting ALEC's involvement with voter-ID laws, the organization shut down its voting and elections task force, "and I don't think that happened by accident," said Spaulding, of Common Cause. "That happened after a sustained spotlight was put on them."

Losing corporate members and disbanding task forces is one thing, but ALEC may have an even bigger problem on its hands. In April, Common Cause filed a whistleblower complaint with the IRS alleging that ALEC's lobbying activities make it ineligible for 501c3 status. Based on 4,000 pages of internal ALEC documents--some obtained through public-records requests and others from inside sources--Common Cause maintains that, "the evidence shows ALEC has an agenda, that they track where their model bills are introduced, that they send out 'issue alerts,' which include updates that go to state legislators where ALEC bills or ALEC-related bills are being introduced, sometimes targeting committees or task force members and including talking points, press releases," said Nick Surgey, Madison, Wis.-based general counsel for Common Cause.

"It's remarkable. Essentially ALEC says that they do not lobby. They are a 501c3, which means that they're a charity, and as a charity, they're able to do some lobbying, but it's limited, and you have to disclose it," Surgey said. "We have 990s going back many years for ALEC and, consistently, they tell the IRS that nothing they do is lobbying. They put a zero or they don't check the box that says, 'Do you do any lobbying, yes or no?' ... They're clearly trying to influence legislation."

If the IRS agrees, and ALEC is found to be in breach of the rules, the organization would have to reincorporate as a 501c4 and fully report its activities as lobbying. What's more, Surgey said there's a possibility that if ALEC is found to have improperly reported to the IRS, tax revenue lost when donations were recorded as tax deductible may be recouped from individual donors--an action that Common Cause included in its complaint.

"It's unlikely that the IRS would go after individual donors, but there's nothing statutorily to say they cannot do that," Surgey said. "They'd have to make a judgment that donors should have been aware. ... Most of the responsibility is on ALEC, but we also believe the corporations should have been aware that ALEC was doing what they were doing, and that's lobbying. ... We believe that they have some liability."

The whistleblower complaint is still working its way through the system, and Surgey said that these kinds of cases tend to take "quite a while." Still, he and others, like Graves at the Center for Media and Democracy, maintain that keeping pressure on ALEC is important for more reasons than just recouping tax revenue.

"It's also about making sure that these really important, fundamental debates happen in the open," Surgey said. "We got into looking at ALEC out of a concern that corporations have too powerful a role in our political system; they have a disproportionate power in the legislatures for a variety of reasons, and ALEC really seems to be the epitome of that."