F–ck you, n–gger!" It was Oct. 1, 1962, and James Meredith was finally a student at the University of Mississippi.

"On the night of September 30, 1962, I entered the most sacred temple of white supremacy in America, the campus of the University of Mississippi at Oxford, Mississippi, and triggered the climax of the most momentous clash between federal and state authority since the Civil War," he writes in his new and very compelling book, "A Mission from God: A Memoir and Challenge for America" (Atria Books, 2012, $25), written with William Doyle.

"I started the whole thing. I am a moment in history."

That he is. But this book is much more than a powerful narrative of the "Ole Miss Riots" of 1962; it takes the reader inside white supremacy in a way I haven't experienced since reading "The Autobiography of Malcolm X."

Like with Malcolm X, you get to know a very complicated man. He is an iconoclast, and he can ramble and puzzle in real life, but don't dare overlook what he can get each of us to think about.

In his book, we walk through the battleground with the friend I always call "Mr. Meredith"--even though his wife, Judy, teases me about it--and feel the deep-seated hate that spews out of people who had supposedly been taught to be proper and sophisticated.

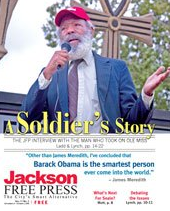

A Soldier's Story: The JFP Interview with James Meredith

Donna Ladd and Adam Lynch interviewed Mississippi icon James Meredith in his Jackson home in 2008. His answers might surprise you.

Here, you really see and hear the ugly from young people raised to hate "those people" in order to protect a backward way of life that ultimately hurt us all. We wake with Mr. Meredith as he gets up at 5:30 a.m. to the sounds of the soldier pacing outside his dorm room in Baxter Hall. We sniff his "sweet-smelling aftershave" as he applies it, and before we reach the bottom step of the stairs out of his dorm, we hear, "Hey, n–gger! There's that n–gger!"

We walk with a dignified, fearless black man and a team of U.S deputy marshals as he goes to class amid a chorus of "n–gger, n–gger, n–gger," sometimes "accompanied by cherry bombs, epithets and broad-daylight shouted threats to kill me." We dodge bricks, sticks, stones, not to mention kicks and attempts to trip him, and us.

As we see the haters watching his dorm steps 24 hours a day, we learn that race hatred isn't episodic; it is constant. Victims live with it each day even as purveyors believe they're trying to save ... something.

Prettily coifed girls yelled vicious words at him alongside the boys. But they could turn sweet again on a dime: "Classes were a different thing. The same little white coed who might be yelling, 'Why doesn't someone kill him?' would act as humane as any other person in America if she was sitting in a classroom," he writes.

But don't call James Meredith a civil rights hero. That's holding him to a lower standard than he desires or deserves, he argues provocatively. And he, like Malcolm X, was and is adamantly opposed to the non-violence that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights protesters adopted. "[T]he rhetoric and vocabulary of the American civil rights movement has always seemed upside-down and backward to me," Mr. Meredith writes. "In fact, I always found it grossly insulting to me, to you, and to every American citizen, because it always begins with the assumption or concession that some or any of our civil rights are up for negotiation."

Again like Malcolm, Mr. Meredith writes that he believed the Movement could not be won in Mississippi without the use of force to meet force--lots of guns, preferably on the hips of federal officers (which he got). Ultimately, although our history books don't reveal this, he was right. This state, which had gotten the richest from slavery, was using violence to keep at least segregation in place: the last vestige of the Lost Cause. And as much we must applaud the courage of civil rights veterans (I do more than he does), many battles wouldn't have been won here without the fear of black men's threats to arm themselves against the Klan--whether the Deacons for Defense or everyday daddies. (See my related story: http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2007/mar/21/fighting-back-in-klan-nation/.)

Mr. Meredith is an enigma--"a real odd bird," he calls himself--but that's why he's so great. In my many conversations with him--at his house, at our office, at Kroger--this hero challenges me to think. Like him, I don't blindly bow to partisanship, but I need to be prodded to think beyond the most obvious answers.

Take the idea of "black studies," which he loathes. I learned much about Malcolm X at Columbia University (also Mr. Meredith's other alma mater). I attended Manning Marable's "Black Intellectuals" class and did research for his Malcolm X project (now a book)--precisely because I wanted to learn vital history nobody taught me at Neshoba Central or Mississippi State. It was one of the more valuable experiences I've ever had.

But I was the only white woman and one of two whites in the class. And that's where Mr. Meredith's challenges come in: Why do Americans study on two tracks? Shouldn't important "black" studies be everyone's history? Isn't "black history" in Mississippi actually all of our intertwined past? How can we become post-racial when we don't study, or read, or interact, in a diverse way? I see it all the time in interns here: black students who've read Richard Wright; white interns who love Willie Morris--and they're lucky if they've heard of the other Mississippi author. I'm still not ready to kill off "black studies," but Mr. Meredith's point is well-taken.

That brings me to Mr. Meredith's "mission from God." Yes, it was to challenge white supremacy, and he changed the state. (I thought of him last weekend in Oxford when I read quotes by Ole Miss's black, and female, student-body president about its first black homecoming queen.) But now it is to challenge us all to really look at systemic racism in our churches, businesses and political life. Most of all, he implores us to support and strengthen public schools, and not allow bigotry to reduce the education kids get--a vital lesson in a state and city where so many people are content to allow their kids to get a lesser education, public and private, because they're only surrounded by others who look and believe and think like them.

"I challenge every American citizen to commit right now to help children in the public schools in their community, especially those schools with disadvantaged students," he writes in his call-to-action chapter. He and other educational experts list multiple ways we can all help our kids and our public schools.

He's so right. We live in a climate where many politicians are trying to weaken, or close, our public schools--and purposefully or not, are content to have an uneducated, crime-infected underclass. We have to work together to break these cycles, and I will make you this wager: If you read Mr. Meredith's book, you will be more motivated to help our schools and use our shared history to make this state a better place. Please give it a try. James Meredith's work is not done. Nor is ours.

More like this story

More stories by this author

- EDITOR'S NOTE: 19 Years of Love, Hope, Miss S, Dr. S and Never, Ever Giving Up

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Systemic Racism Created Jackson’s Violence; More Policing Cannot Stop It

- Rest in Peace, Ronni Mott: Your Journalism Saved Lives. This I Know.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Rest Well, Gov. Winter. We Will Keep Your Fire Burning.

- EDITOR'S NOTE: Truth and Journalism on the Front Lines of COVID-19

Comments