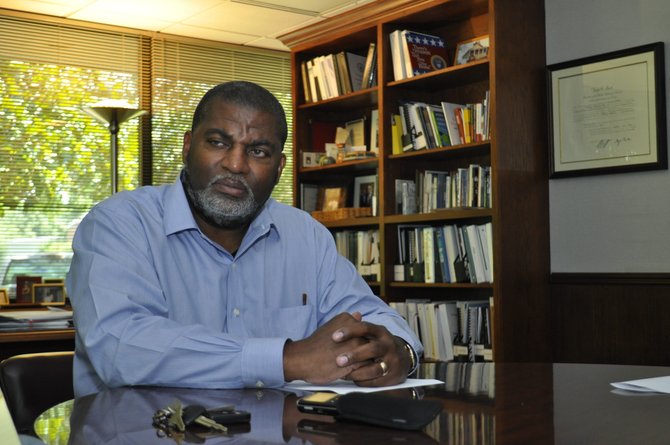

Bill Bynum, chief executive officer of Hope Enterprise Corp., said payday lenders are spreading like wildfire in Mississippi. Photo by Trip Burns

Three years ago, when Diane Williams starting experiencing unusual sharp pains in the back of her leg, the discomfort grew so severe that she visited a hospital emergency room. At the time, she was already seeing her doctor a lot and, even though she had health insurance, Williams incurred enough out-of-pocket expenses that the bills continued to mount.

She turned to a local neighborhood financial institution—Tower Loan.

Headquartered in Flowood, Tower Loan operates storefront consumer-installment loan businesses in more than 150 cities in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, Missouri and Illinois. The company markets itself as a solution for people who encounter unexpected expenses, providing short-term loans to cover situations like Williams' doctor bills.

"They were real nice," Williams recalls of the day she walked into the store to borrow more than $500. "I didn't have a problem getting a loan with them at all. It didn't take very long."

Williams says she made monthly payments on time, but the loans' high interest rate took a bite out of the paycheck she earns working for a local government agency. So she became a repeat customer. Sometimes, she would take out more loans in addition to money she had already borrowed.

"The note was real expensive, but I needed the loan so bad because I was trying to get rid of those medical bills," Williams said.

Mississippi Gold Rush

Williams' story serves as a Rorschach test for customers of consumer-installment and payday-loan businesses.

The lenders would consider Williams' experience a win-win: She took advantage of their service to get herself out of a financial jam and, in doing so, helped Tower Loan make a profit and provide jobs to Mississippi residents. On the other hand, critics of businesses that offer small, short-term loans argue that to earn a fast buck, the companies exploit the desperation of poor people and people of color who often lack access to traditional banks.

Eventually, a co-worker introduced Williams to Hope Credit Union, which loaned her the cash to pay off her Tower Loan bills and charged her a much lower interest rate—17.2 percent instead of Tower's 29 percent.

Bill Bynum, chief executive officer of Hope Enterprise Corp. and Hope Credit Union, said Williams is pretty typical of people whom Hope has helped to get out of what he calls "debt traps"—quick-cash lenders count on customers not being able to pay the money back on time, he said. Borrowers then need to extend the life of their loan, incurring more fees.

"While on the surface, it's marketed as a short-term service for emergencies, payday loans, in reality, are not that. When the average loan rolls over nine or 10 times, that's not a short-term loan," Bynum said.

And the long-term profit picture for quick-cash lenders—which include payday-advance companies, title-loan businesses, installment lenders and pawnbrokers—looks bright. Nationally, short-term lenders rake in fees totaling between $3 billion and $4 billion annually, and they frequently have the backing of the nation's largest banks, including Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo. These businesses handle an estimated loan volume of $40 billion every year.

Mississippi is particularly fertile ground for the industry. In total, more than 1,000 short-term lenders operate in the state, records from the Mississippi Department of Banking reveal. MDB regulates the industry under the Check Cashers Act.

In 2011, the Center for Responsible Lending and Consumer Federation of America surveyed state regulatory agencies and published a state-by-state breakdown of payday-loan fees. Mississippi tied with Wisconsin for the highest annual-percentage rates charged, at 574 percent. The survey shows that Mississippi's $267 million in annual fees collected ranked fourth in the nation behind California, Texas, Louisiana and Florida.

"They see Mississippi as a very profitable place to do business," Bynum said. "I have no qualms with reasonable profit, but I think there's a level of reason, and then there's a level of greed, of abuse."

An Effective Lobby

Although some states are tightening restrictions on quick-loan businesses, Mississippi's lawmakers have had a large hand in helping the industry expand.

Paheadra Robinson, consumer-protection director for the Jackson-based Mississippi Center for Justice, has seen payday lenders wield influence with lawmakers.

"There are (legislators) who sincerely believe that predatory lenders are providing a service. For them, it's going to take being more connected to their constituents to understand the plight of consumers mired in predatory-lending debt," Robinson said. "But there are those that willfully turn a deaf ear to what's going on within this industry because they are supported through lobbying efforts by predatory lenders."

A review of campaign-finance records reveals how powerful that lobby is. Since 2011, Tower Loan alone has donated $73,500 to legislative candidates; since 2003, the company has given $187,796 to state politicians.

The industry's lobbying organization, the Mississippi Consumer Finance Association has made $255,559 in political contributions since 2003. Top recipients include Gov. Phil Bryant, who collected $32,000 from 2007 to 2011, and Insurance Commissioner Mike Chaney, who got $16,000 for his re-election efforts during the same period. Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves received $15,000. The top legislative recipients were Rep. Nolan Mettetal, R-Sardis, and former Rep. George Flaggs, a Democrat, who resigned his House seat in July to become of mayor of Vicksburg. MCFA also contributed $5,000 each to Mississippi State Supreme Court justices, Josiah Coleman and Randy "Bubba" Pierce.

Payday-loan watchdogs say it's not surprising that the industry has been able to score so many legislative victories. During the 2013 legislative session, lawmakers removed an important oversight mechanism by repealing the Check Cashers Act's sunset provision. As a result, lawmakers will not be required to review the law periodically; instead, a lawmaker would have to author a new bill and usher it through the committee process.

"There's no consistency across the country in terms of what's allowable, and Mississippi has been one of the more lenient states," Hope Enterprise's Bynum said.

The Next Fight

Mississippi's political climate is unlikely to sweep in major reforms. Instead, consumer-rights advocates are setting their sights on modest legislative tweaks and financial literacy efforts.

Advocates have seen some success in recent years. In 2011, lawmakers capped payday-loan fees at $20 per $100 and extended the time for borrowers to repay the loans from 14 days to 30 days.

Even with the changes, Mississippi continues to hold the distinction as the state with the most payday lenders per capita and some of the nation's highest interest rates—despite Mississippi's economic standing as the poorest state in the country.

"While I appreciate clarity in terms of the rates, what people need more are protections that are affordable and not abusive," Bynum said.

Hope Enterprise also offers financial counseling and literacy workshops, and has a program for young children that teaches kids and, as importantly, their parents, the importance of saving.

"Part of (our) strategy is to get them into a relationship with a depository. Borrow from yourself, and if you do have a need for a short-term loan, you can borrow at a non-predatory rate," Bynum added.

Robinson, of the Center for Justice, echoes Bynum's call to start teaching financial literacy at a young age.

"If we can start with the middle-school-aged children, then that gives us an opportunity to make things better for our state. With us leading the nation in poverty we have to do things differently," Robinson said.

Comments