Making the Dec. 23 deadline could be dicey for people in Arizona and the 35 other states where the federal website healthcare.gov is the path to coverage, as well as Oregon and Hawaii, which have struggled to get their sites functioning.

This story appeared on Kaiser Health News.

Tambra Momi has been eagerly awaiting the promise of guaranteed health insurance. Since 2011, she has battled Dercum's disease, a rare and painful condition in which non-cancerous tumors sprout throughout her body, pressing against nerves. Jobless and in a wheelchair, Momi needs nine different drugs, including one costing $380 a month, to control the pain and side effects. No insurer has been willing to cover her, she says, except a few that have taken her money and then refused to pay for her medications.

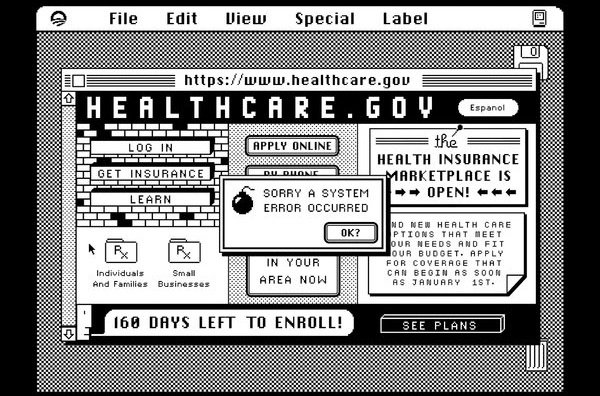

Yet her effort to sign up for the health law's coverage has been painful in its own way. Momi, a resident of Fort Mohave, Ariz., hasn't been able to complete an application on the federal healthcare.gov website. Three attempts to submit an application over the phone haven't panned out. Once when she called back, she says she was told they had no record of the application. Another time, officials told her they could see the application but couldn't open it.

"I was so elated with this whole thing," Momi, 46, says about the health insurance marketplace, "and now I'm praying to God that I'll be able to get something."

Enrollment has been open since Oct. 1, but hitches such as those that Momi encountered have put many people behind schedule. The next three weeks are critical for consumers keen on getting health coverage as soon as the health law allows it on Jan. 1. People who desire coverage by then need to sign up in the new marketplaces no later than Dec. 23. Consumers can still enroll up to the end of March, but their coverage will begin later.

For people in the states with well-functioning insurance websites, such as California, New York and Kentucky, this appears to leave plenty of time. But making the deadline could be dicier for people in Arizona and the 35 other states where the federal website healthcare.gov is the path to coverage, as well as Oregon and Hawaii, which have struggled to get their sites functioning. On Sunday, the government reported progress in improving healthcare.gov, saying the site now allows more than 800,000 visits a day with the rate of timeouts or crashes reduced to below 1 percent. Officials said repairs continue.

The technological trials for these websites have turned an enrollment period that was supposed to be a leisurely three-month stroll into a last-minute sprint for millions of Americans. "The challenge ahead is you have a lot of people who need to get into the system," said Sarah Lueck, an analyst with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington think tank that focuses on issues related to low- and moderate-income people.

Prompt Enrollment Threatened

Within the Obama administration, concern is great enough about accommodating everyone who wants coverage by the first of the year that officials pushed back the deadline from its original date of Dec. 15.

Prompt enrollment is urgent for people in several circumstances. Some have no coverage, either because they haven't been able to afford it or, like Momi, because they have pre-existing medical issues that led insurers to reject them in the past. Some have insurance that is going to expire. That group includes people whose health plans have been canceled and those in a high-risk pool that is closing. For people with serious medical issues, such as cancer patients in the middle of treatment, the loss of coverage could be medically and financially devastating.

Sara Collins, a vice president at the Commonwealth Fund, a New York health care foundation, predicts two waves of people will try to sign up for plans in the first half of December: those who had tried to shop on the websites but were stymied by technological glitches and those who were able to look at plans but didn't settle on one.

For those who wait until the Dec. 23 deadline—either by choice or because they encountered difficulties—insurers will have just a week to process the applications before people can start filing claims. Robert Laszewski, an insurance industry consultant, says insurers generally need two weeks to add newly covered people into their computer systems. "The chances are we're going to see lots of customer service problems," he says.

'Nobody Knows What Accident They Can Be In'

Sandra Fox, a psychiatric social worker in Pittsburgh, has been trying to buy insurance through the marketplace since the day it opened at the beginning of October. After many failed attempts to get on healthcare.gov, she succeeded. But the website said she and her husband, an artist, are not eligible for a government subsidy while she believes they are. (Based on information she provided, KHN calculated they are eligible for a $292 monthly subsidy.) She was told to mail a written appeal, but despite sending it off Nov. 1, her case remains unresolved.

Fox's husband goes to a pain clinic and uses medication for his spinal stenosis. She fears if they are not enrolled in new insurance when their current policy lapses at the end of the year, they will have to pay out-of-pocket. "It would be extremely expensive," she says. "And nobody knows what accident they can be in tomorrow. I don't think it's wise to be without insurance for one day, frankly."

Early mix-ups occurred in the launch of the last major federal health expansion, the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. People were supposed to sign up by Dec. 31, 2005, to start using the benefit when coverage began on Jan. 1, 2006. But that turned out to not leave enough time for Medicare to process all the enrollments. "There were all these stories about people showing up to pharmacies and the pharmacies not having the seniors in the systems," said Sabrina Corlette, who directs the Health Policy Institute at Georgetown University. "And the seniors walked away empty handed because Medicare hadn't transferred the information."

Momi's pain is so intense from her disease, formally known as adiposis dolorosa, that any delay would be agonizing. "I have lipomas, fatty tumors that grow throughout my body," she says. "They're attacking through my spine, my internal organs. My nervous system is actually growing through them. You can see them."

She drives monthly to Las Vegas, more than 100 miles north of Fort Mohave, to see her doctor. He wants to install a pain pump for a new medicine from sea snail venom, but it's so expensive she has had to delay the surgery. "My doctor is helping me so much I can't even begin to tell you," she says, crying. "I pay him what I can pay him."

No one knows how many people might still be clamoring for coverage at the cusp of Christmas. When Massachusetts launched its health insurance exchanges, the big spike in enrollment did not occur when the program began in 2007; it occurred when the financial penalty for not signing up kicked in that December, according to a study by Harvard professor Amitabh Chandra and other researchers.

For the federal law, the comparable time is the close of the enrollment period at the end of March. After that, people without health coverage face tax penalties of $95 or 1 percent of income, whichever is greater, unless they meet the criteria for exemptions. Chandra, however, notes that there are differences from Massachusetts' experience that make it less than a perfect comparison. For one, the Massachusetts penalty was higher than the federal health law's penalty in the first year. On the other side, he noted that more people in the United States are aware of the health law's penalty "because we've had a four-year fight about [the law]; nothing like this had happened in Massachusetts."

Laszewski says the political controversy over the rules may have left consumers confused. "Is my policy really canceled? What do all these objections from insurance commissioners really mean? The consumer is left in the lurch trying to figure out what is going on," he says.

Kirsten Sloan, a policy director for the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, says that is not the case with those most desperate for medical care. "Many people living with cancers and survivors who have been waiting, they know these deadlines," she said.

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.