Mississippi isn’t doing enough to satisfy a lawsuit against the state’s foster-care system. Photo by Courtesy Flickr/M Glasgow

Jamison J. had shuffled through 28 foster homes, mental institutions and temporary shelters, by the time he was 17 years old. In the first of the homes, when he was 4, his foster mother terrorized him by shoving Jamison in front of her two snarling, growling dogs.

A Mississippi Division of Family and Children's Services caseworker had removed Jamison and his sisters from their mother, who was physically abusing and neglecting her children. DFCS separated the boy from his sisters.

Over the next seven years, Jamison was lucky to be in two loving foster homes in addition to the abusive first placement. His third foster family wanted to adopt him. Instead, DFCS sent him back to his biological mother, where he witnessed his mother's boyfriends beating her and watched them repeatedly abuse a 2-year-old. Jamison saw the little boy thrown into walls and whipped with an iron belt inscribed "Boss."

Despite the trauma in the household, DFCS declared Jamison's reunification with his mother a success. The agency gave the youngster, by now 11, two days to collect his belongings and say goodbye to his foster parents in Jackson. While he was gone, the 2-year-old died, beaten to death for wetting his bed.

Jamison, troubled and angry, never received appropriate mental-health care. When he acted out, DFCS placed him in psychiatric treatment facilities where doctors drugged him unnecessarily. His mother overdosed and died. When he was 16, the agency tried to place Jamison with his biological father in Kansas, but officials there wouldn't certify the home. Jamison's father had been incarcerated 37 times, couldn't keep a consistent address and had threatened to hurt his son.

DFCS forgot to pick him up at the Jackson airport when he returned to Mississippi. Ignoring renewed adoption requests from his foster parents, the agency sent the young man to Oakley Training School, a juvenile correctional facility. Jamison was never accused of any crimes.

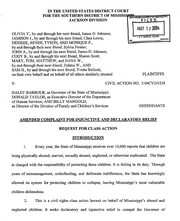

In 2004, Jamison J. became one of more than a dozen defendants in a civil-rights class action lawsuit filed against then-Gov. Haley Barbour and the then-directors of the agencies charged with caring for Mississippi's youngest citizens in need, Donald Taylor of the Mississippi Department of Human Services and Billy Mangold of DFCS.

Jamison had been in the state's "care" for close to 13 years by the time Olivia Y. v. Barbour hit the federal court in Jackson. The case began what has turned into nearly a decade of child advocates trying to drag Mississippi's foster-care system into the 21st century. By most accounts, the state is barely lifting its well dug-in heels.

In March 2007, Mississippi signed a settlement agreeing to stop contesting the suit and admitted that the state violated the rights of the children. Later that year, the state agreed to a plan to reform its foster-care system. In July 2012, Mississippi agreed to a modified plan after it failed to reach substantive milestones of the 2007 reform plan. The 2012 plan gave Mississippi additional time to put the reforms in place.

Now, seven months into the new plan, Grace Lopes, the court-appointed monitor, says that while Mississippi has made some progress, it is taking far too long to go too short a distance. Her newest report is no more hopeful than those she filed previously, every six months since the state established its first foster-care reform plan in '07.

"[P]rogress still appears to move slowly," Lopes wrote in her Jan. 25 report to the court, presented Feb. 21. "... [D]efendants stand before the Court in the sixth year of the remedial process unable to satisfy many of the Settlement Agreement's core data reporting requirements about their own performance."

It's a critical issue, said Marcia Robinson Lowry, founder and executive director of New York City-based Children's Rights, a nonprofit child advocacy group. The lack of data from the state makes it impossible to gauge whether Mississippi's foster-care system is making improvements for the children.

"You can't tell how the children are doing if you don't have reliable data," she said. "The fact that you've got a system that's responsible for the lives and well-being of dependent children that doesn't have dependable data is in itself pretty alarming."

Mississippi has done a few things to improve the system, Lowry said, including hiring additional caseworkers and instituting training; however, the DFCS continues to lag far behind the rest of the country in maltreatment of its foster children. That rate is at least five times the national standard, based on DFCS' own reports, making the state either the worst or the second-worst in the country for rates of abuse and neglect of children in foster care for many years now.

Without good data, it's difficult to get a good handle on how big the problem is.

"We don't have a breakdown at this point as to whether (the maltreatment) is in foster homes or in group care," Lowry said, calling all of the data "suspect."

"There's just much too much that we don't know. We do think that the rate of maltreatment is under-reported."

Lopes cited serious problems with maltreatment investigations. In her report, the monitor came to the conclusion that the problem is bigger than the scant data suggests.

"The lack of urgency with which defendants are proceeding is unacceptable in light of the impact the deficits in their performance have had and continue to have on the safety and well-being of the nearly 3,800 children in DFCS custody," Lopes wrote.

"There's real reason for concern here," Lowry said, adding that the laxity is due to insufficient management, leadership and commitment on the part of Mississippi as well as little enforcement.

"There have been no consequences so far to the state," she said. "... They're not getting the job done."

Calls to the Department of Family and Children's Services have not been returned.

Comment at www.jfp.ms. Email Ronni Mott at [email protected].

Comments

Use the comment form below to begin a discussion about this content.

comments powered by Disqus